When I first started writing for Mad in America, I initiated a series called “False Arguments,” that I said would be a ‘three-part story.’ I wrote the first two parts almost right away.

The original ‘False Arguments: A 3 Part Story’ was authored in January of 2013 and spoke to the strange and misguided ways in which we approach language and labels for people seen as being ‘in’ the mental health system. I followed that up in April of the same year with, ‘False Arguments, Part 2: Anti Anti-Stigma.’ Then I got stuck. There was so much to write about, and none of it quite fit in with the ‘false arguments’ premise… So, I let it go. I figured the ‘right fit’ would eventually come to me. And so it has.

To re-cap from that original blog, here’s what I meant by ‘false arguments’:

In my experience, the world of ‘mental health’ is absolutely overloaded with what I like to call ‘false arguments.’ Literally every day, people are engaged in debates without ever questioning the premises upon which those debates are founded. It’s akin to my husband approaching me and inquiring, “Hey, should we fill our one-year-old daughter’s sippy cup with Pepsi or Coca Cola today?” followed by us arguing out the various virtues of the dueling soft drinks without ever bothering to wonder why on earth we’d even offer soda to our sweetly innocent and unsuspecting toddler in the first place. In other words, sometimes the biggest problems can be found not in the best arguments of opposing sides, but in the assumptions of the questions themselves.

What would happen if we simply started asking ‘Why?’ more often? WHY do we believe what we believe? WHAT would happen if we dug beneath the most typical arguments and looked for a different starting point? HOW did we get to this point, and is it the right one? And of course, WHO was it that led us here and how precisely did they come by that power?

And so that brings me to False Arguments, Part 3: Why do people hear voices? (And why do we need to know?)

I am a part of an organization (the Western Massachusetts Recovery Learning Community) that offers an increasing amount of Hearing Voices training throughout the United States. These trainings are based on the philosophy and approach of the Hearing Voices Movement and perhaps best outlined here on the Intervoice (international Hearing Voices) website. Inevitably, during the course of such trainings, the conversation eventually finds its way to ‘but why do people hear voices?’ That question tends to rise up with the greatest urgency after we’ve offered challenges to medicalized perspectives. (As in, “Wait, you just rocked my world. Everyone I know has always said this is all an illness, and they’ve said so with such certainty. So, If not disease, then what?!”)

Most often, this question does not come from people who hear voices themselves. It comes from people in provider roles, and – with the greatest frequency – from parents. As a parent myself, I understand the desperation to make things ‘okay’ for one’s child (especially when they’re very much not). I can empathize (pretty deeply) with the sense of fight and search for answers that can grip a parent in the most difficult moments. I get it.

That need to know comes from a genuine place. It comes from the (sometimes desperate) belief that ‘knowing’ is the gateway to ‘helping’, and the need to believe that there is (has to be!) an answer. In some instances (particularly when trauma perspectives are being discussed), it may even come from a desire to be absolved of blame one’s self, which is also real and understandable. But, what if it’s the wrong question entirely? What if focusing in on ‘why’ (at least in the most objective sense) actually pulls us further and further away from the ‘helping’ that we most aimed to seek?

In truth, the Hearing Voices trainers with whom I work do talk a great deal about ‘why.’ They share their own stories and how they’ve come to make meaning, and they also offer examples of ways others have made sense of their experiences. They acknowledge (though de-emphasize) conventional medical perspectives, as well as a trauma framework, but they don’t stop there. They also discuss spirituality and a number of other nuanced ways that someone may come to explain such phenomenon.

However, they do all this from the angle of supporting someone to find their own meaning, which bears little to no resemblance to traditional manners of searching for globalized truth. In fact, really the only answer to ‘Why do I hear voices,’ – at least from a point-of-view that’s rooted in the Hearing Voices movement – should be ‘I don’t know’. And, not in a dismissive manner… but in a collaborative one. As in: “I don’t know, but here’s how some people make sense of it…” or, “I don’t know, but what thoughts do you have about it?”

Admittedly, not knowing is scary, and many people won’t like that answer. Being told ‘the truth’ by someone who pretends to know it, can undoubtedly provide some degree of relief (even if only temporary). But, to offer any one answer as if it is ‘the’ answer inevitably limits someone’s options, and may steer them away from what will ultimately work for them. (It may even steer them toward something that will cause great harm.) Most importantly, it simply isn’t honest.

In trying to strike a balance and offer some examples of ways people do make meaning, our trainers (and anyone else who should engage in such a dialogue) also tend to come up against another barrier: People hear alternative frameworks as ‘symptoms’ or insubstantial side notes, and thus sometimes feel they haven’t been offered any alternative frameworks at all. More often than not, no matter what we say, people seem to translate our words into something along the lines of:

- “It’s a disease or it’s…. something else… but we’re not telling you what because we don’t know and all we’re really trying to say is it’s probably not a straight-up disease. You figure it out from there. See ya!”

OR:

- “It’s a disease or it’s trauma. It has to be one or the other, and since no one has identified any real associated disease, then it’s probably trauma. What, you say you haven’t experienced any trauma? Had a pretty happy, healthy childhood? Oops, sorry! Better start digging ‘till you remember some forgotten traumatic memory or something!”

OR (my personal favorite):

- “Hey, we don’t know what’s going on, but not because there isn’t an answer. It’s just that we don’t know it because we’re not ‘professionals.’ So, please, next time you do a training, be sure to bring in a psychiatrist, ask them all the wrong questions, and go back to being comforted by what you already ‘knew’: It’s all a disease.”

The reality is that those who claim ‘proof’ and specific, concrete ‘knowledge’ will generally be listened to over anyone claiming that the best (and truest) answer is no clear answer at all. (This is especially true in cultures where a comparatively small handful of years of academic study are valued far more than decades of personal experience.) And, so we do seek to strike a balance; We aim to offer concrete examples, while still emphasizing the importance of a stance that ultimately says, “I don’t know the truth for you.” And when someone does share the truth they’ve come to for themselves (as Jacqui Dillon stated in ‘Beyond the Medical Model’), we emphasize the importance of exploring what actual impact that truth has on that person’s life rather than evaluating the truth they’ve come to as it relates to our own belief systems.

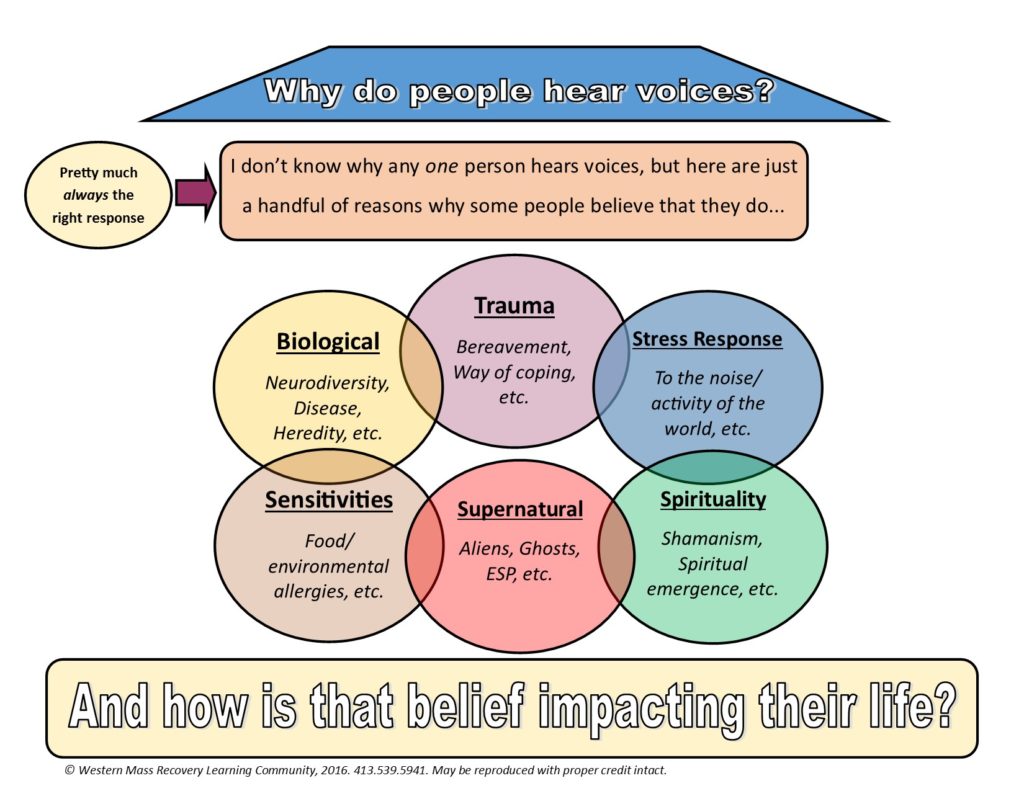

To that end, we’ve created a handout to help concretize the tricky balance of all those ideas, and have shared it at the end of this blog for your perusal.

And for anyone contemplating Hearing Voices training, a few additional notes:

If you want to start a Hearing Voices group or have a Hearing Voices event of some sort, and aren’t sure if you have or want to invest the budget needed to bring someone in from the outside to help you out along the way, Hearing Voices USA offers a great tool to help you evaluate how much outside support is needed. You can find that HERE. (The Hearing Voices Movement certainly isn’t set-up like, for example, Welness Recovery Action Planning and so no certification is required for someone to be ‘allowed to’ facilitate a group or offer a workshop, but the risk of getting it wrong or failing to hold to the integrity of the approach without that sort of support is pretty high, unless you’re fairly well prepared.)

And if you do want to bring someone in, visit our Hearing Voices page for information. We are also working with the Hearing Voices Research & Development Fund (through the Foundation for Excellence as administered by Jacqui Dillon and Gail Hornstein) to provide free trainings, and you can learn more about that HERE. You can also contact us directly at:

General inquiries: [email protected]

Caroline White, Lead Trainer & Training Coordinator: [email protected]

Lisa Forestell, Lead Trainer: [email protected]

Marty Hadge, Lead Trainer: [email protected]

Caroline also facilitates a nationally accessible monthly phone-in support group for existing and/or aspiring facilitators. (If you want to learn more about that call or join in, e-mail Caroline for details.)

Also of note: Although the Hearing Voices Movement offers support and resources under an expansive umbrella to anyone who hears voices, sees visions, or has had a variety of other unusual experiences, we are intentional about ensuring that all of our lead trainers have their own substantial hearing voices experiences that they’ve successfully integrated into full lives. For any ‘Hearing Voices group’ facilitator trainings, we are also intentional about assigning only those lead trainers who have extensive Hearing Voices facilitation experience, as well.

This is all done to ensure the highest quality trainings. However, and perhaps more importantly, it is done in recognition of the principles of social justice, including acknowledgement that this movement should be led by people whose voices have historically been silenced, and the importance of people who hear voices getting to speak for themselves.

—————–Hand Out – Page 1 ——————–

FOR A PDF COPY OF THIS HANDOUT CLICK HERE

—————–Hand Out – Pages 2 & 3 ——————–

Anyone is capable of hearing voices given the right set of circumstances (fever, isolation, lack of sleep, etc.). But the ’why’ often isn’t so clear, and the Hearing Voices approach suggests that the right answer to this question is always going to be ‘I don’t know.’ This is because:

- There is no real way (no definitive test, etc.) of knowing the root cause for any one person

- Although there is typically a most commonly believed/accepted reason, what that reason is can shift over time or between cultures. This goes further to suggest that reasons are based more on belief systems than on any one ‘right’ answer.

- Input from hundreds of thousands of voice hearers across the world suggests the importance of supporting people to make meaning of their own experience far over and beyond having an external meaning pushed on them.

Just a handful of perspectives that people may use when making meaning of voices include:

Biological: The most commonly accepted explanation for voice hearing in most Westernized cultures is medical or biologic in nature. However, even a biological perspective does not necessarily mean ‘disease’ (though that is the most common interpretation). Biological explanations can also include heredity that isn’t disease-based (i.e., saying that there is a hereditary link between family members who hear voices is not the same as saying there is a hereditary link of illness, as voice hearing doesn’t need to be regarded as sickness or ‘bad’). It can also include physical injury, or ‘neurodiversity’ which simply speaks to brains that are differently wired without the assumption that one is inherently better than the other. (Perhaps there could even be an evolutionary quality to voice hearing where it has been deemed a positive or negative trait based on environment.) Unfortunately, the only biological perspective that is widely discussed and promoted is one based in a disease model, and it’s important to remember that—in spite of being the most popular explanation– no biological link has been objectively or scientifically proven (i.e., no definitive genetic link or disease process has been identified).

Sensitivities: In some instances, this may be a nuance of a ‘biological’ perspective in that its possible that some people’s biological make-up may lead them to be more sensitive to certain elements. Others may develop these sensitivities based on environment. Regardless, for some, sensitivities to things like lack of sleep, food or chemicals (etc.) in the environment, or to drugs (both prescribed and otherwise) may lead to the experience of voice hearing.

Trauma: Trauma is generally defined by the individual (no one else can really say what trauma is or is not for someone else) and can be understood to be anything that leads that person to believe that the world is an unsafe place that is unable to meet their most basic needs (at least without substantial adaptation on their part). It may be the result of one big event or a series of smaller events or conditions (like racism or poverty) that have cumulative impact . One of the most common alternative explanations to a biological perspective is one based in trauma. In fact, research based on the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study suggests that people with an ACE score of 7 or higher have a 700% greater chance of hearing voices. Many who experience voice hearing as a result of trauma also interpret the voice hearing experience as a way of coping or as an adaptation that helps them survive in the world in some way. For example, some may come to learn that even a scary voice is simply meant as a warning about an environment that may be dangerous for them (or at least is believed to be dangerous based on past trauma experiences).

Stress Response: Closely related to a trauma perspective is a ‘stress response’ perspective. Similarly, a ‘stress response’ may come about when someone finds the world or an event overwhelming, even if they wouldn’t define it as ‘trauma’ per se. For example, some people find living in the chaotic environment of a big city (with all its noise, movement, and rush) to be overwhelming at a sensory level. If they’re not able to move and live in an environment that allows them to feel more at ease, they may develop voices (or any other number of stress responses) as a result. Again, for some, they may see this as a way of coping (at least initially), rather than necessarily as ‘maladaptive’.

Spirituality: The founders of the Hearing Voices movement developed some of their earliest understanding of this concept when comparing religious and medical interpretations of voice hearing. Specifically, Patsy Hage (a voice hearer and founder of the HV perspective) asked Marius Romme (her doctor and one of two co-founders) why his religion’s acceptance that some may hear the voice of their god was any more valid than the voices she herself heard.. This led Marius to re-consider his assumptions about Patsy’s experience (and the experience of voice hearers in general). In fact, many religions and spiritual frameworks include histories of people hearing voices of ancestors, deities, and so on. Within that context, many see this experience as a gift, or process of emergence or the finding of one’s true self that can be a meaningful process if someone is supported to integrate that experience into this world in a way that allows them to continue to walk through it. There is also a perspective called ’spiritual emergency’ that is gaining traction in the world, and speaks to the challenges sometimes faced when one is going through that process.

Supernatural: This perspective is sometimes closely related to a spiritual perspective, as (for some) supernatural experiences may be connected to their spiritual beliefs. Regardless, this perspective may include when someone hears the voice of deceased relatives or friends, or any number of other experiences including, for example, when someone believes their voices are the result of an alien transmission or the voice of some other supernatural being. This perspective is the one most likely to be disregarded as a ‘symptom’ of illness rather than a legitimate way to understand the voice hearing experience. However, for many people, this is a powerful way of making meaning that has positive impact on their life. For those of us who have difficulty accepting frameworks that seem to ‘weird’ or difficult to understand based on our own beliefs, it may be most important to keep reminding ourselves that it is, in fact, the impact someone’s beliefs has on their lives that is most important.

And how is that belief impacting that person’s life? Coming to an understanding (whether based on conventional wisdom or something that seems very foreign from it) can be an important and healing process, and will often require supporters to let go of their own pre-conceived notions. Questions that may be useful in this process include: Is the person invested in this way of thinking? Did they come to this conclusion or has it been pushed on them? Does this belief have any negative consequences, and if so, what does that look like? What about positive impacts? Does the person want to explore other ways of making meaning of their voices or other unusual experiences? It’s also important to note that how someone explains their voices is very different than what they do or don’t wish to do about them.

FOR A PDF COPY OF THIS HANDOUT CLICK HERE

Thank you Sera for distilling so many concepts into a concise format.

Report comment

Sure thing, Marty. 🙂 Thanks for all your work in this department, as well! 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Thank you, Sera.

You write so clearly and with humor and empathy. Seems like “certainty” is in such demand in our culture that we often close ourselves to discovery. The quickest, cheapest answers get the buzz, and we fail to even consider the underlying presuppositions of our questions. Coming to accept “not knowing” is a process of growing and learning that has led me to a more loving, joyful experience.

In reading your blogs, I often think about the opportunities you give your children and others to grow and learn with acceptance and love. It’s a warm and pleasant gift to read your thoughts. Thanks.

Report comment

Thanks, Berta. 🙂 I appreciate your taking the time to comment here, and for all the experience and knowing of the ‘not knowing’ that you bring to all this work, as well 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Hi Sera,

your piece here comes down to the core of what so-called “modern psychiatry” seems to be actively denying: that each human being is unique in themselves, their context and experiences and so the way to understand each person’s experiences must be as unique and specific to each individual as they are themselves.

Yes, there can be some value in “classification and categorisation” in helping to promote communication and understanding but – not at the expense of forgetting that we all live, grow and develop in relationships with others and in context.

Hearing voices is possibly one of the most obvious examples of an experience that the psychiatric approach has de-humanised by describing and labelling it as understandable in only the one, disease-model way. For many, the experience of voices that others can not hear is not a negative one, for others their voices are much better managed by learning to understand and co-operate with them.

To automatically assume that someone hearing voices must have those voices silenced can cause so much harm… x

Report comment

Thanks, Kallena, Agreed on all counts! I really appreciate the clarity with which you approach and speak about this issue. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Thank you again Sera! Tolerating uncertainty is part of Open Dialogue and part of any humble, person-centered approach to partnering with/supporting people through/with various intense personal experiences. My hope is that we honor the time and space it takes for people to find meaning in their experiences, including voice hearing rather than asking the wrong questions and jumping to unsupported conclusions. Thank you for presenting this in such a concise and helpful way.

Report comment

Thanks, Truth. 🙂 I agree, it’s a part of any and so many worthwhile approaches… And yet, it’s perhaps one of the toughest concepts to learn it would seem, based on all that apparently needs to be unlearned to get there. Always reaching for new ways to facilitate that process!

Thanks for reading and commenting,

Sera

Report comment

OMG you’re forcing me to think at 10 pm on a Sunday. So:

they do all this from the angle of supporting someone to find their own meaning, which bears little to no resemblance to traditional manners of searching for globalized truth. In fact, really the only answer to ‘Why do I hear voices,’ – at least from a point-of-view that’s rooted in the Hearing Voices movement – should be ‘I don’t know’.

Don’t know if you followed Bonnie B.’s “Spitzer” blog discussion what but what we were talking about is what she called the “decontextualization of behavior,” i.e. taking seemingly similar outward behavioral (in this case perceptual) traits which have specific meaning only to the individuals involved, calling them “symptoms” and lumping them together into categories of “disorders.” Who says voices are “symptoms” of anything?

I don’t have any direct experience with this. (I remember being asked by the admitting doctor at the state hospital whether I heard voices; I replied “I hear yours.” He didn’t respond.) However, it seems like this may just be an idiosyncratic method of processing information coming from the environment/universe. “I don’t know” seems as satisfactory a response as any. People don’t spend as much time urgently focusing on “why” other people are gay anymore; this seems comparable.

Report comment

Sorry for asking you to think so late on a Sunday, oldhead. 😉

I haven’t been following Bonnie’s blog discussion, but yes, for sure, much of this is about ‘decontextualization’ of ‘behavior’ (or ‘experience’, I’d prefer to say).

Interesting comparison with the search for why someone is ‘gay’. I think there are some crossovers there that are worth consideration… In fact, I almost always find that the crossovers between movements and oppressive processes have many similarities worth exploration.

Thanks for reading and responding 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Sera,

I have to disagree with some of the points of this article. First, with regard to the question, “Why do people hear voices?”, “I don’t know” is a weak and incomplete answer. It may be true on an individual level that we cannot initially know what is leading to such experience, but on a group/aggregate level, we know quite a bit about what causes voices, delusions, hallucinations, and other anomalous experience. The ACE Study and other research by John Read has shown that child abuse, war trauma, poverty, bullying, racial and ethnic discrimination, economic inequality, and other social stresses are very strongly correlated with reports of psychotic experience, and almost certainly causally associated with them too. Of course it would be incorrect and overgeneralized to say that X always causes X, but that does not mean that some areas or factors are more important than others. Furthermore, some individuals have a pretty clear idea ab initio of what experiences are causally linked to their voice hearing, and we should not foist the generalization “I don’t know” onto them. Some people do know.

For example, if the answer to What Causes Voices is “I don’t know”, it might be equally likely that Flying Piglets, Vladimir Putin, Manchester United, the planet Neptune, or being beaten every day for years as a child cause voice-hearing. But we know that on a group level the last one would be much more likely to cause these experiences (presuming one doesn’t live in Russia). Of course the individual should still be approached from an attitude of curiosity and uncertainty, listening to their story, and trying to collaboratively discover with them what factors might play into their experience of voices or other extreme “symptoms”. In other words, the opposite approach of most American mental health care “professionals.” But we do have some good data showing that stressful social experiences strongly link to voice-hearing… and conversely, we do not have any clear replicable data showing that genes or errant brain chemicals are causing these phenomena. People should know these things.

Furthermore, the “I don’t know” approach, while well-intended, is not going to work for many people who are desperate for some simplistic explanatory framework to make sense of their experience. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the work of Otto Kernberg, Heinz Kohut, James Masterson, Harold Searles, etc.; but they basically understand psychotic processes as representing a predominance of splitting (meaning viewing things as all good or all bad) along with extreme use of the defense called fusion or non-differentiation (meaning being unable to differentiate between what is oneself and others, and what is internal and external). People who experience heavy use of these defenses are not able to tolerate ambivalence well (at least not yet) and often can only conceptualize things in simplistic all-good or all-bad terms.

People often want to say, “It’s better to be ambivalent and see shades of grey”. But one clinical approach to this type of psychotic person (based on Gerald Adler and Jeffrey Seinfeld’s work) emphasizes that such a person will not be able to tolerate ambivalence and complexity until or unless sufficient relational security and an “average expectable environment” is provided for some length of time. In other words, until they have engaged in a trusting relationship of some length, and had their basic needs met for some time, psychotic and borderline people are not yet able to safely experience the threatening complexity of not knowing. These are the people who are likely to swallow and believe the medical model lies, and the I Don’t Know approach is unlikely to impact them. I believe what they would be helped by is a strong positive approach that emphasizes recovery is possible and that meaningful causes of psychosis do exist, at least on a group level, and are usually psychosocial.

I suggest approaching such people with the psychosocial trauma approach which draws on the data I mentioned above, showing that for most, not all people, trauma, lack of love and other psychosocial stresses are crucial. This is what I have done with my site BPDTransformation, speaking to many people labeled BPD who are looking for a more hopeful explanatory framework, to good effect. I do not tell them I know everything or am sure what the cause of their distress is, but I do talk to them about psychosocial factors common to many people so labeled, and I privilege those factors above biological and other explanations, because I believe they are much more important.

Report comment

BPD,

I don’t disagree with what you’re saying regarding what we know from a group/community perspective, but I think you are misunderstanding some of this article or applying it in ways I didn’t intend…

For example, I am definitely speaking from an individual perspective and not a group one.

Additionally, I’m definitely *not* suggesting that ‘I don’t know’ be used to argue with individuals who DO feel like they know. In actuality, the whole point of much of this approach is about supporting whatever meaning people come up with individually *whether or not* it fits with the what we believe generally, *whether or not* it makes us uncomfortable, and so on… And I really don’t mean that to be coming from a patronizing place, either. It’s coming much more from a ‘I can’t possibly know where this is coming from for YOU, so my job is to support you to make sense of that for yourself…’

I also don’t think that starting from I don’t know means that we can’t offer all of that information… In fact, there’s a part of the blog where I speak specifically to ‘I don’t know’ not being the end point, but rather a beginning point to collaboratively supporting someone to explore options (which can certainly include sharing what we know about research, and so on as you suggest above…).

I don’t entirely disagree with the rest of what you write (particularly with introducing people to some of the most common and useful frameworks such as a trauma-based one), BUT I do to some extent… Because I’ve seen the harm and alienation people have experienced by having a ‘trauma’ framework pushed, as well…

As I noted in the blog above, the people asking this question most frequently in training settings are NOT people having these experiences themselves, but parents… If I were having this exchange with someone who was hearing voices themselves and it was clear that they were frustrated with the ‘I don’t know’ sort of answer, I *may* very well shift to one that is more along the lines of, “While I don’t know for you specifically, I do know that framework x [trauma-based] has been really helpful for many people…” and go from there. But it feels pretty important to me (and most consistent with the HV approach) not to start there…

Regardless, thanks for taking the time to read and comment 🙂 There is much that I find true about what you offer!

-Sera

Report comment

we know quite a bit about what causes voices, delusions, hallucinations, and other anomalous experience. The ACE Study and other research by John Read has shown that child abuse, war trauma, poverty, bullying, racial and ethnic discrimination, economic inequality, and other social stresses are very strongly correlated with reports of psychotic experience, and almost certainly causally associated with them too.

How can you identify as being anti-psychiatry and say things like this, based on “studies” which perpetuate the “other”-ization of people’s experience and behavior (albeit from a liberal-leftist paradigm)?

Report comment

Oldhead, these are quasi-experimental studies showing general trends about distressing experiences that people report. Of course, I do not agree with the labeling used or the notion that their experience makes them ill or other. But if you read John Read’s research in Models of Madness, you can see there is much more of a focus on experiences/specific “symptoms” than on “other-ization” or labeling, and very much of a focus on rejecting the medical model/otherization.

People can cite studies like this while understanding that labels are simply discriminatory and often misleading terms that people are given, not illnesses. Citing them doesn’t mean one endorses or believes in labeling or otherization.

I am anti-psychiatry in my own way; there is no one person or body that can say that my antipsychiatric views are wrong or right.

Report comment

It seems to me that this statement correlates people who experience social crimes and ‘psychosis.’ I think this could very easily lead to re-victimization, because it can undermine that person’s credibility. I think it’s a false belief, too much open for interpretation that in the end, supports the bigotry in system.

Report comment

How do the ACE study and John Read’s studies perpetuate other-ization, in your opinion?

Report comment

This is what I was wondering; if Oldhead has actually read the cited material.

Report comment

No I haven’t read them because it’s besides the point, my reaction (which I haven’t managed to completely put my finger on) is not to any particular study but to your approach, which, aside from the constant validation of medical model terms like “psychosis,” seems to reinforce what Sarah is trying to dispel, which is that there is a “something” (if not a “mental illness”) which needs to be categorized, explained and (by implication) controlled.

I’m not seriously challenging your anti-psych “credentials” btw, just suggesting that this might be a contradiction within a contradiction you should explore.

Report comment

And I mean Sera, of course, not “Sarah.” I’m really screwing up names today for some reason.

Report comment

Oldhead,

I do not think that psychosis is a medical model term to the same degree that schizophrenia is, although better terms might be severe emotional suffering, extreme distress, anamalous experiences (as Paris Williams writes about), extreme states of mind, or some other subjective term.

I think that severe emotional suffering is a “thing” or real experience that is individual and different in each person, but nevertheless can be understood as existing at a group level on a continuum of severity which fades into psychic well-being / satisfaction / enjoyable functioning in work or relationships.

This is the psychoanalytic developmental approach that I like so much. The divisions are arbitrary, but the notion is that when developmental needs (for love, security, support of independence) are not met in some way, then a person responds to the offending neglect/abuse/trauma with a call for help or an expression of suffering (“symptoms”) that gets mislabeled “psychosis”, “schizophrenia”, etc. I am saying it here in the kindest language I can. I do think some general linguistic descriptions can be used for this type of experience, although it is better to focus on subjective qualitative experience, stories, and distressing experiences (“symptoms”) rather than any worthless labels like schizophrenia.

I do not think there is one schizophrenia, or one psychosis, that can be reliably described and applied to an individual case… and of course we do not need any more futile attempts to control people’s distress with coercion, drugs and so on.

Report comment

I do not think that psychosis is a medical model term to the same degree that schizophrenia is, although better terms might be severe emotional suffering, extreme distress, anamalous experiences (as Paris Williams writes about), extreme states of mind, or some other subjective term.

What makes it less of a medical model term? (Anyway, don’t you often speak of “schizophrenia” too, albeit in quotes?) Looking for an “alternative” term implies that there is a “something” that needs to be labeled. As has been pointed out there are numerous instances in which people labeled psychotic are not suffering emotionally (though they may be causing other people to suffer). Others who are experiencing extreme emotional distress are not labeled “psychotic.” So there goes that as a defining characteristic. “Anomalous” is basically defined as “unusual” (though listed synonyms include “aberrant” and “abnormal”). That hardly qualifies as a meaningful category. “Emotional distress” is a real “thing” but cannot be equated with or defined as what is meant or implied by “psychosis.”

(To be continued.)

Report comment

Well, Oldhead, some real things are out there. At least I hope so (otherwise maybe everything I see and experience is just a delusion!). The how-to of labeling or identifying aspects of the external world question is thorny. But if we go too far in the direction of not naming or identifying anything at all, it becomes hard to communicate.

Having some imperfect shorthand is sometimes necessary for talking about complex phenomena, although one should be careful with how one uses it.

Psychosis is a vaguer less medical term than “schizophrenia” in that it is generally used to refer to a range of extreme emotional suffering / experience and not understood to represent one reliable/valid illness or condition, as schizophrenia falsely claims to. Most fake medical studies are done on people falsely labeled with so-called schizophrenia, not psychosis.

Report comment

Wasn’t referring to the studies (see my other comment).

Report comment

Though I see the way I phrased it all was misleading.

Report comment

Sera,

I concur, thank you for speaking out on this matter. I agree, too, that one does want to know what caused one to hear “voices.” In my case, I first heard “voices,” two weeks after being put on psychiatric drugs, exactly when the drugs were to “kick in.” So I was quite certain the “voices” were the result of the psychiatric drugs. But, of course, all doctors I expressed this concern to initially, vehemently denied this as a possibility.

Eventually, I was weaned off the drugs, and the “voices” did go away. But I then suffered from a drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity “manic psychosis.” Which resulted in a forced hospitalization, and massive drugging. I was let out, after my insurance company refused to pay for any more of these “snowings.” And, was once again on a couple psych drugs, and once again had the “voices.” Which reconfirmed my belief that it was, in fact, the psych drugs which caused me to hear the “voices.” But again, doctors denied this as a possibility. Although, I was finally weaned off the drugs again.

At which point, I started researching medicine, because I wanted to be able to medically explain what had caused me to hear “voices.” I did eventually find the medical proof my “voices” had been caused by bad “bipolar” drug interactions, which were known to cause “psychosis,” via the central symptoms of anticholinergic intoxication syndrome, aka anticholinergic toxidrome.

I will mention my psychotomimetic “voices” did “help” me overcome my denial of the abuse of my child, since those “voices” were the “voices” of the people at whose home my child was abused, bragging incessantly about the abuse. And, some decent nurses did finally hand over the actual medical evidence of the abuse in my child’s medical records, which definitely forces one to admit to the reality of such an atrocity.

But my drug withdrawal induced “super sensitivity manic psychosis” was not “voices,” thus it was a very different type of “psychosis.” It was, for me, an awakening to my dreams, an introduction to the concept of the collective unconscious. It was more like a mid life crisis reflection on all the kind people I’d met in my life, whom I was reminded of as I listened to different songs from different periods in my life. And it was as if all these former friends and teachers wanted to help me heal, and assure me that my former psychiatrist’s claims that I was “irrelevant to reality” were untrue.

This so called “psychosis” / awakening did then turn into an odd spiritual tale of my supposedly obtaining eternal life, and culminated in Jesus supposedly claiming it was time for the final judgement. And, to this day, I still awake every morning, with the understanding that God and Jesus, and for whatever reason my subconscious self, are supposedly still in the process of dividing those who will be written in the “book of life,” from those who will not, within this theoretical “collective unconscious.”

I’m basically fine with this spiritual awakening to my dreams, since the promise is that of a better world for all the decent people in the future. And I do see the need for an improvement in our current society, especially after my appallingly unethical and disingenuous dealings with the psychiatric system.

Thus, I agree, it’s best to be honest, and let people find their own meaning in their unusual experiences. I can and do have hope, which is the opposite of what today’s psychiatric industry claims is possible for those who’ve experienced “psychosis” or “voices.” It is truly morally wrong to lie, and claim one has medical proof of what does or does not cause “psychosis” or “voices,” when one does not actually have such medical proof.

And what if there is a “collective unconscious,” and we are all to be connected some day both within the unconscious, and maybe even in our waking hours? Which no doubt, could allow for an amazing and wonderful evolution of human kind. A world where we collectively work together for the betterment of all, rather than compete with each other and fight never ending wars? Who knows, but hope is a good thing, as is honesty. And, no one, not even psychiatrists, know how humanity is supposed to evolve. Sometimes it’s good to say, “I don’t know.”

Report comment

Thanks, Someone Else… For sharing so much of your own story, and particularly for highlighting the potential impact of psych drugs in being at the root of these experiences for some people. That is not the first time I have heard that story (and of course, Elizabeth Kenny speaks to it quite well in her show ‘Sick’), but it runs so counter to the accepted narrative that people seem to need to some how ‘unhear’ it or see it as ‘symptom’ most of the time.

Thanks again, Sera

Report comment

Great article Sara- personally I believe there’s a reason for everything– good bad or in between– and that within every reason their’s an answer that will clearly show the why– and that its knowing/understanding the why that heals– the knowing– the reason– reason is sanity– is necessity– is what keeps us well. Finding the reason/sense for things is in words or time and maturity– never in a pill– or rarely– and that’s why forced poisoning is the crime– and although we know we have to have it for some at certain times– but for very short periods is OK– to stop the onset or escalation of symptoms– but to me the symptoms have a real cause– and that’s not a name calling mental illness–although we can understand a need to name something to show what we see and understand collectively–but its what caused it- not a name and a condition we need to manage that came from the cause –especially when its to be overcome– its a reason with an answer and healing from that –that counts–matters. And that’s why im saying forced drugging has to stop– or at least give every person the right to be able to attempt with assistance withdrawing when they say its harming them–doesn’t matter if you consider them this or that uninsightful– seeing that its their body and mind– their heart–their emotions–that we cant see– and know very little about– and science knows very little about– how about people in science who don’t know about the buried deep emotions–probably in all of us– that causes the surfacing of troubled-debilitating thoughts or thinking– again like they do to all of us at some point- give them the decency in assumption as another human being — knowing we all get troubled –in diagnosis. Why do they want to make people their drug experiment– make them take a tag– take management when that’s for those who are really-truly mad– and who may never recover– why are they putting everyone in the same basket and managing-drugging them for a lifetime– that’s the crime– the lifetime they steal– that they drug uncomfortable– and then don’t listen to the cries and the pain of what they’ve done– don’t give them the opportunity to prove them wrong– or themselves right– which doesn’t really matter anywhere near as much as getting your sanity back–your sense of trust and safety–your freedom- no all of a sudden–your sanity- freedom–trust–doesn’t matter because were fixing your brain- and us fixing your brain is what matters– not what matters to you– your UN-INSIGHTFUL– yet they know the problems they had- they’ve ovecome–like we all do 99/100– but are forced to endure debilitating drugs- for something your well and truly over– just like “someone else”–who im responding to– so this isn’t just another of the many people being forced to take what harms them— but maybe more importantly- its the type of person in charge at the asylum, and not so much -what they’re doing we need to stop first. its the misery mind set of psychiatry that’s really killing us all–The trouble here is that they only have 20% of the madness out there–the GPs have the other 80%– even though their sending on another 20% back to the bin for the psyche–from the damage — the psyches very greedy–and wants more of the action$– which is why they lie and instead of seeing and calling what nine times out of ten bin returns are– neuroleptic withdrawal psychosis– they call it “a real mental illness withdrawal” — back to your real mental illness– see their line–see their lie–see their angle—- which is what it is an– ANGLE– an angle that keeps the till full– at the expense of their “forced drugged debilitated from it –client. I haven’t failed–what I do isn’t harming–hasn’t harmed– im a good guy– yeah sure and pigs might fly too.

Report comment

But if we go too far in the direction of not naming or identifying anything at all, it becomes hard to communicate.

Who suggested not identifying anything at all? We are talking about misidentifying phenomena which cannot be categorized based on outward similarities, for which any label is inappropriate.

Psychosis is a vaguer less medical term than “schizophrenia” in that it is generally used to refer to a range of extreme emotional suffering / experience and not understood to represent one reliable/valid illness or condition, as schizophrenia falsely claims to. Most fake medical studies are done on people falsely labeled with so-called schizophrenia, not psychosis.

What do you mean by “a less medical term”? In what way? And why is vagueness considered a component of good communication? Find me a psychiatric text where “psychosis” is not considered to be “mental illness.”

Also, the way I look at it any“medical” studies of any of these false categories are flawed from their inception, even the “better” ones, if they start out with categories of mental “diseases” as part of the studies’ premise.

Report comment

Thank you for this PDF. I work in a state “hospital”. I’m on my way to the administrative offices with numerous copies of it to put in people’s boxes. One of the things I’m working to do is to disprove the assumption that all voice hearing is bad and must be suppressed before people can be freed from the “hospital” where I work. This PDF is concise and easy to understand and is a good place to begin in trying to educate people about the Hearing Voices Network. Thanks.

Report comment

Sure thing, Stephen. I hope it ends up being useful… And yes, it’s such an important point that voice hearing is not necessarily bad, as well as that – even in instances where it’s disturbing for someone – the goal doesn’t *have* to be to try and get rid of the phenomenon to help someone improve the experience. I wish you luck in your efforts.

-Sera

Report comment

Hi Sera!

I followed the link from your current blog to this one. You probably aren’t following this anymore, but I’ll add my 2cents.

First, I think what you are offering sounds great! Maybe some day I can get my wife to take a more activist stance like I said on your current blog. The problem is she doesn’t know how good she had/has it with how our son and I supported her, and she got tired of how she got treated by the online d.i.d. community because her experience was so different than what is typical, and so she just doesn’t seem to have any interest in reaching out and helping others. I hope some day that changes!

With my wife’s d.i.d., I can remember her first calling the other girls(voices) ‘aliens.’ Fortunately, I took the path of validating her ‘voices’ and treating them as if they were ‘no big deal’ and eventually she (my wife’s ‘host’) was able to do the same as we brought 7 other girls into our family and relationship.

But along the way, as I lived 24/7 with them/her, I started to realize that her ‘voices’ were just kind of a normal part of one’s mind…and taking her lead, I learned to hear my own ‘voices.’ It was kind of like learning to listen to your small intestines. When everything is fine, it’s REALLY hard to hear them hum along doing what they do, but when something is putting stress on them, they can get pretty loud. But in the end, the noises are just a normal, natural part of how our intestines work whether the noises are audible.

Though I think the ‘why’ is important for myself personally as I’ve learned to listen to my mind so that I can figure out a proper response and also monitor things internally, when I’m dealing with my wife, I mostly focus on the ‘what’ to enter into her experience so that I can validate her experience, and respond appropriately within the context of what she is experiencing. It’s much easier to walk WITH her in her mental experiences and give her stability or whatever else she needs/wants, than to proclaim ‘from on high’ how she ought to view her experiences externally.

I will admit I have a problem seeing the ‘why’ of the voices as irrelevant, however. Universal negatives are hard to prove but the supernatural and spirituality seem unlikely even though I spent most of the earlier years of my life calling myself a Christian and desperately seeking those experiences. BUT, that said, I love the example that was given on MIA recently of a patient who would only ‘glub, glub’ like a fish and the person who was able to reach that person was the one who got down on the floor and ‘glub, glubbed’ back! That person got it! We have to enter into the reality of the person and it is from there that we can reach them and help them IF they want and need it.

For the last 9 years, I have lived in the reality of the 8 girls in my wife’s system. Only one views me as her husband. To the rest I am a friend, boyfriend, or daddy. But I walk with them and slowly their reality is healing and changing. One other girl wants to marry me now, and her BFF is dating me. And slowly the 7 girls are moving toward the fact that they are all part of my wife even if they don’t understand that yet.

It’s important for me to know the why so that I can be the best healing partner possible. I don’t use that knowledge to give her dictates, but so I can be more compassionate and understanding as I walk the healing journey with her.

Sam

Report comment