In June, the Centers for Disease Control reported that the suicide rate in the United States had increased 30% from 1999 to 2016, with more Americans killing themselves “than ever before.” The CDC has been sounding this alarm for several years now, stirring headlines—each time it issues its annual report—of a “public health crisis.”

Here are just a few of the headlines that have appeared:

- “The Neglected Suicide Epidemic”—The New Yorker

- “The Unseen Epidemic”—Baltimore Sun

- “How Suicide Quietly Morphed into a Public Health Crisis”—New York Times

- “America’s Suicide Epidemic is a National Security Crisis”—Foreign Policy

Although the media reports may tell of social factors that can contribute to suicide, such as unemployment, the language in the articles often tell of a medical crisis. “Mental health experts say mental health screening would help people get into treatment before their depression becomes severe,” Voice of America News wrote, in an article on the CDC report. “Other recommendations include reducing the social stigma associated with mental illness and making treatment more widely available.”

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, which has been promoting suicide awareness programs since the late 1980s, similarly tells of how “ninety percent of people who die by suicide have a mental disorder at the time of their deaths.” The most common disorder associated with suicide, the Foundation states, is “depression, an illness that goes undiagnosed and untreated far too often.” It advises reporters to “convey that suicidal thoughts and behaviors can be reduced with the proper mental health support and treatment.”

This rise in suicide certainly deserves societal attention. But given that it has occurred during a time when an ever greater number of people are getting mental health treatment, there are obvious questions to investigate, with the thought that perhaps our societal approach to “suicide prevention” needs to change.

Specifically:

- Is suicide in the United States really at an “epidemic” level? Or is there a bit of “disease mongering” present in such claims?

- What do we know about societal risk factors that could account for changes in the suicide rate during the past forty years?

- Are there guild and commercial interests present in “suicide prevention” campaigns?

- Is there evidence that suicide prevention campaigns work? Does more access to mental health treatment lead to a reduction in suicide?

- Do antidepressants reduce the risk of suicide?

In short, we need a scientific fact-check on suicide in the Prozac era. The hope is that doing so might help our society respond to this suicide crisis in a more “evidence based” way.

The Epidemiological Data

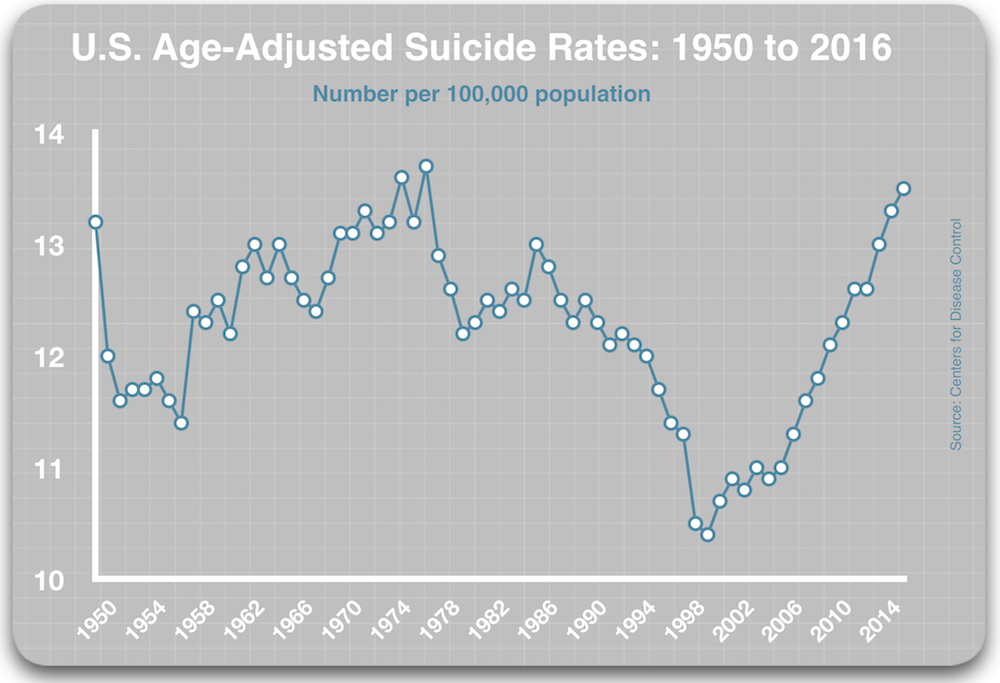

The Centers for Disease Control, which was founded in 1946, has been reporting “age-adjusted” suicide rates since at least 1950.1 An “age-adjusted” rate—as opposed to a crude rate—takes into account the fact that the risk of suicide increases as people age, and thus as a population grows older, the suicide rate could be expected to slightly rise.

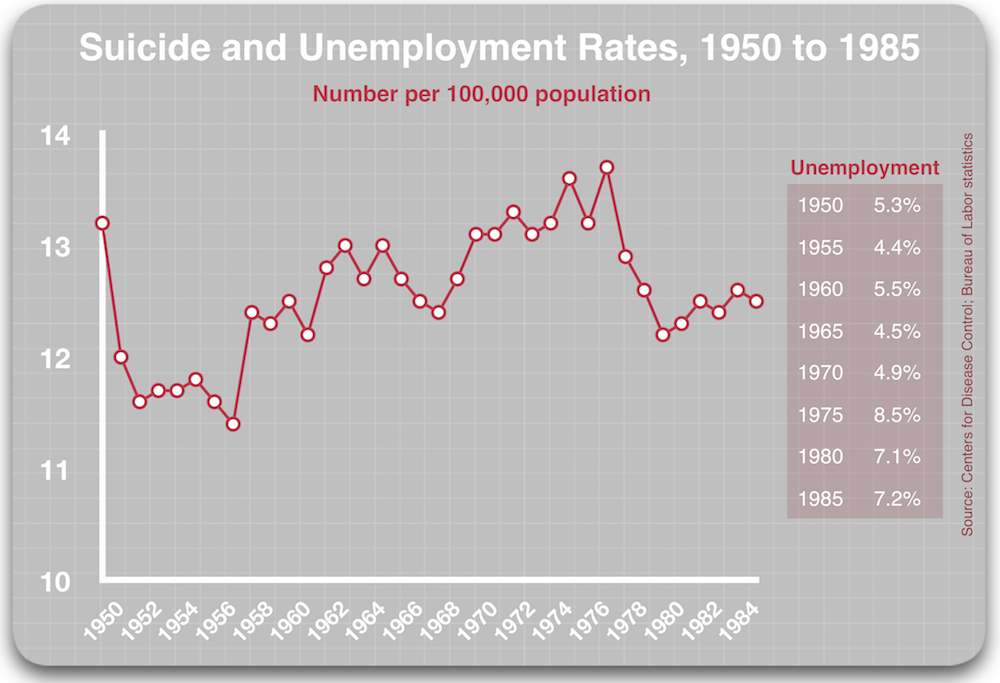

The first surprise in the CDC data is how relatively stable the age-adjusted rate was from 1950 to 1985. In 1950, it stood at 13.2 per 100,000 population, and then, over the next 35 years, the rate varied from a low of 11.4 per 100,000 in 1957 to a high of 13.7 per 100,000 in 1977. The rate mostly ranged from 12 to 13 per 100,000 during that 35-year period, oscillating slightly from year to year, perhaps partly in response to the health of the economy.

The suicide rate stood at 12.8 per 100,000 in 1987, which was the year that Prozac was approved by the FDA. Over the next 13 years, the rate dropped to 10.4 per 100,000, which was the lowest it had been in the fifty years that the CDC had been reporting age-adjusted rates.

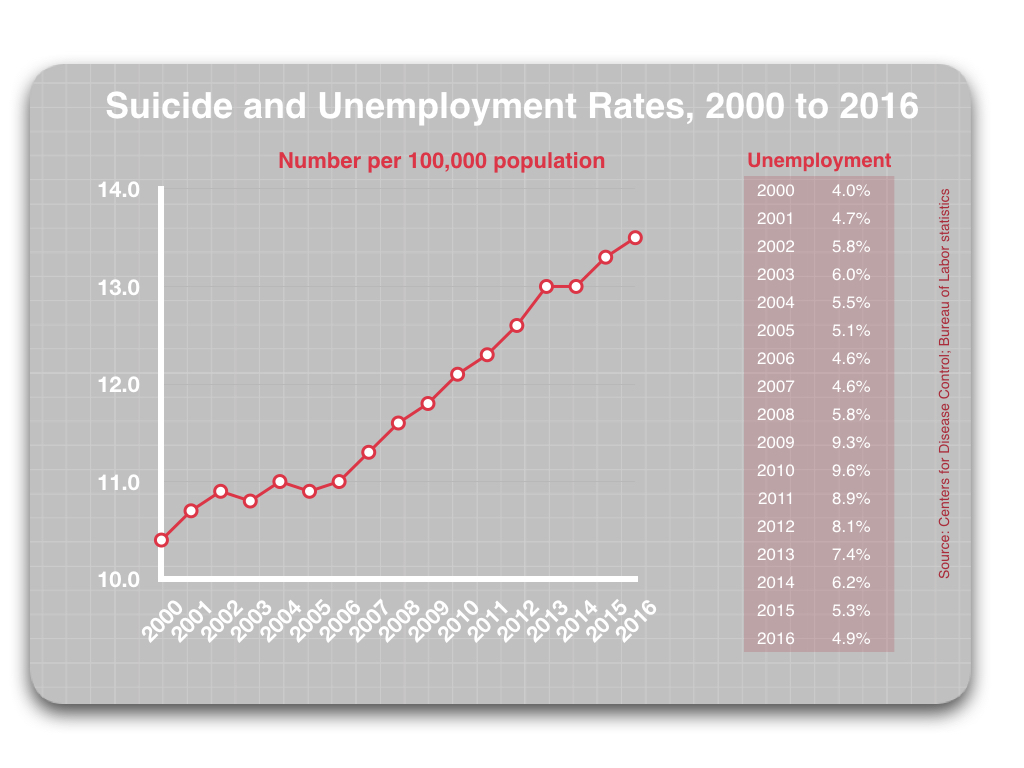

This decline led to pronouncements by leading American psychiatrists that Prozac and the other SSRIs were the likely reason for this decline. However, since 2000, the rate has risen steadily, even as antidepressant usage has risen. The suicide rate hit 13.5 per 100,000 in 2016, which was slightly higher than it was at the start of the Prozac era, stirring the recent alarms about this hidden “epidemic” in our midst.

While this historical review—at least at first glance—presents a confounding picture about the possible impact of antidepressants on suicide rates, it does belie the claim that our society is suffering an “epidemic” of suicide.

What we see in the epidemiological data is that the suicide rate today is only slightly higher than it was in 1950 (those halcyon days of yore), and not much higher than it was in 1987, at the start of the Prozac era. And so what we really need to investigate are the risk factors present in our society that could possibly explain the changing suicide rates.

Why did the suicide rate drop from 1987 to 2000? Is there a “risk factor” that can be identified that would have such impact? And why has it reversed course since then? Is there a risk factor that could be propelling the rate upward?

If answers to these questions can be found, then there is the possibility that our society could craft societal policies that would reduce existing risk factors for suicide. This would also help us assess whether our current approach—which conceptualizes suicidal thinking as a symptom of a mental disorder that needs to be treated, usually with an antidepressant—is helpful, or conversely, may be driving suicide rates higher.

Risk Factors for Suicide

There are, of course, many factors that contribute to suicide, and most are best described as personal stresses and struggles—relationship breakdowns, divorce, poor physical health, legal difficulties, financial problems, unemployment, loss of housing, substance abuse, and so forth. These are problems that are ever-present in a society, affecting some percentage of the population each year, and naturally they can be intertwined with depression and other emotional difficulties. Undoubtedly this is one reason that there has been a steady “baseline” suicide rate for the past 70 years. Life can knock you down in a variety of ways.

Unemployment is a marker of economic hardship, and there is some evidence that the suicide rate rises and falls, to a small degree, in concert with changes in the unemployment rate. The high-water mark for suicide in the United States occurred in 1932, when the Great Depression was in full swing. As the Depression eased, so too did the suicide rate.

The 1950s and 1960s were mostly decades of full employment, with unemployment typically in the 4% to 5% range, and so any year-to-year changes in the suicide rate can’t be tied to any significant economic difficulty. However, the unemployment rate did spike to higher levels from 1971 to 1985, ranging from 4.9% to 9.7% during those years, and the yearly suicide rate also ranged higher during that period, hitting a high of 13.7 per 100,000 in 1977.2

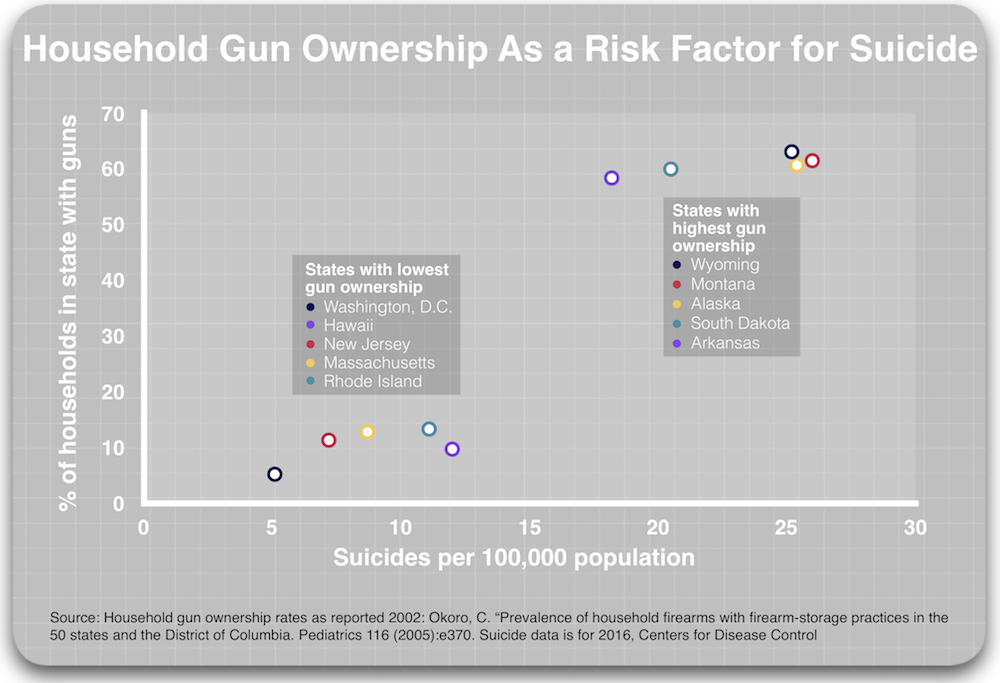

The second well-known risk factor for suicide is household gun ownership, as research has found that this has a dramatic impact on suicide rates. In a review of 14 studies that examined this risk factor, researchers from the University of California, San Francisco concluded that people who live in homes with firearms are three times more likely to die by suicide.

The second well-known risk factor for suicide is household gun ownership, as research has found that this has a dramatic impact on suicide rates. In a review of 14 studies that examined this risk factor, researchers from the University of California, San Francisco concluded that people who live in homes with firearms are three times more likely to die by suicide.

However, this increased risk is not because people who have access to firearms are more suicidal than the norm, but rather because access to a gun increases the likelihood that a suicide attempt will be fatal. This is why men are three times more likely to die by suicide than women, even though women are more likely to attempt suicide. Men are much more likely to use a firearm.

The dramatic effect that gun ownership has on suicide rates can be clearly seen in the variation in state suicide rates. The suicide rate in the five states with the highest rates of household gun ownership rates are two to five times higher than in the five states (including District of Columbia) with the lowest rates of household gun ownership.

Thus, the first place to look for a change in a risk factor that may have impacted changing suicide rates from 1987 to 2016 is household gun ownership. The second would be changes in unemployment levels, as this can be a marker of financial distress.

A period of decline: 1987-2000

In 1987, when the national suicide rate was 12.8 per 100,000, 46% of households had a gun. There was a dramatic decrease in home gun ownership over the next 13 years, such that by 2000, only 32% of homes had a firearm. This meant that 14% of the population converted from high-risk suicide status to low-risk status.

Although the arithmetic is a bit complicated, based on the finding that people living in households with a gun have a three-fold higher risk of suicide, the conversion of 14% of the population into low-risk status could be expected to lower the suicide rate to 11.0 per 100,000 in 2000, all other things being equal. (See calculations.3)

In addition, a drop in unemployment likely had a slight impact on the suicide rate. It decreased from 6.2% in 1987 to 4% in 2000, and, based on a 2015 Lancet study, that could be expected to lower the suicide rate another .5 per 100,000 population.

Based on the changes in these two risk factors, the 2000 rate—if all other things were equal—could have been expected to be around 10.5 per 100,000. In other words, these two factors alone could have accounted for the drop in the suicide rate from 1987 to 2000, with the increase in antidepressant usage, rather than being a causative agent for the drop, just going along for the correlative ride.

2000 to 2016

From 2000 to 2016, the suicide rate rose from 10.4 per 100,000 to 13.5 per 100,000, with this rate rising in steady fashion, year after year. However, this rise cannot be explained by changes in the risk factors cited above.

From 2000 to 2016, the percentage of households with a firearm remained stable, at around 32%. There was no change in that risk factor.

As for unemployment levels, they stayed fairly low from 2000 to 2008, spiked in 2009 and 2010 when the economic crisis hit, and then steadily declined from 2010 to 2016, such that they were back down to 4.9% in 2016. Indeed, as seen in the following table, the suicide rate rose irrespective of changes in the employment rate.

Thus, in 2016, the percentage of households with a gun was the same as it had been in 2000. The unemployment rate was basically the same too. Yet, even though economic and gun-ownership risk factors were alike in 2000 and 2016, the suicide rate was 30% higher in 2016 than it had been in 2000.

Moreover, the increase in suicide during the 16 years was seen across all “ages, gender, race and ethnicity.” It is almost as though an unseen “risk factor” for suicide was suddenly dropped into the water.

It is during this period that suicide prevention programs became a regular part of the societal landscape. These campaigns urge people to get into treatment, and this contributed to a continued increase in the prescribing of antidepressants. These programs are expected to decrease suicide rates, but given the rise in suicide that has occurred in lockstep with the advent of such efforts, an obvious question is whether suicide prevention campaigns, which conceptualize suicide as a medical problem, could be contributing to the 30% jump in suicides since 2000.

The Rise of Suicide Prevention Programs

Although the nation’s first “suicide prevention center” opened in 1958 in Los Angeles, with funding from the U.S. Public Health Service, government focus on suicide remained low-key throughout the 1970s and the 1980s. Then Prozac came to market in 1987, and it was at this moment, when American psychiatry was eager to promote this new SSRI as a breakthrough medication for depression, that families who had lost someone to suicide formed the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. As the non-profit states today, it was the “first nationwide organization dedicated to understanding and preventing suicide through research, education, and advocacy,” and it’s fair to say that it is this organization, more than any other, that has shaped our societal thinking about suicide during the past two decades.

In its first few years, the Foundation successfully recruited a scientific advisory board populated by academic psychiatrists who specialized in mood disorders, and while this was an organizational achievement that, from a grass-roots perspective, made perfect sense, it nevertheless opened the door for a mix of academic psychiatrists and pharmaceutical company executives to take over the intellectual and financial leadership of the organization. This was the very “alliance” that was proving to be so successful at selling SSRI antidepressants, and the Foundation’s suicide prevention efforts soon were of a complementary kind.

The rise of academic psychiatrists to positions of leadership in the Foundation got its start in 1989, when David Shaffer, chair of child psychiatry at Columbia University, received the Foundation’s award for research in suicide. He soon launched his Teen Screen initiative, which sought to screen teens and adolescents nationwide for signs of depression and suicidal thoughts, and in 2000, just as national implementation of that effort was getting underway, he was named president of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Shaffer—like nearly all U.S. academic psychiatrists in the 1990s and early 2000s—had financial ties to pharmaceutical companies. He served as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and Wyeth, and as an expert trial witness for Hoffman La Roche. In 2003, at the request of Pfizer, he sent a letter to the British drug industry stating that there was insufficient evidence to restrict the use of SSRIs in adolescents, even though the FDA, after reviewing the clinical trials of SSRIs in those under 18 years of age, had put a “black box” warning on the drugs, telling of how they doubled the risk of suicidal thinking in this age group.

Other academic psychiatrists who subsequently served terms as presidents of the Foundation similarly had financial ties to industry. After Shaffer finished his term, J. John Mann, a colleague of Shaffer’s at Columbia University, was named president, and he had financial ties to GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, serving as both a consultant and expert witness. Next up was Charles Nemeroff, who, during his time as Foundation president, burst into public view as the nation’s poster child for industry’s corruption of academic psychiatry.

Nemeroff was named Foundation president in 2008. At that time, he was chairman of psychiatry at Emory University, and he had a long-standing involvement with the Foundation, having been on its scientific council for more than 10 years, and a member of its board of directors since 1999. He was one of the best-known psychiatrists in the country, valued by numerous pharmaceutical companies as a “thought leader” who could help sell their products, and in the fall of 2008, Senator Charles Grassley reported that he been paid more than $1 million by various pharmaceutical companies, money that he had failed to properly report to Emory. GlaxoSmithKline alone had paid him more than $800,000 from 2000 to 2006 for an estimated 250 talks he’d given promoting Paxil to his peers and the larger medical community.

As for Pharma’s direct influence on the Foundation, this took off in 1996 when Solvay Pharmaceuticals, maker of the antidepressant Luvox, pledged $1 million to the foundation. At the time, this was the largest gift in the Foundation’s history, and Solvay CEO David Dodd was quickly named to the Foundation’s Board of Directors (and would subsequently become chairman of the Foundation). The Solvay pledge opened the industry floodgate, for, as a 1997 Foundation press release announced, after the Solvay donation, “many other corporations have joined forces to support the effort.”4

Thus, within a decade of its founding, psychiatrists with ties to the pharmaceutical industry were providing the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention with its scientific leadership, and it was being heavily funded by industry. At the foundation’s 1999 gala Lifesavers dinner, the corporate sponsors included Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Solvay, Abbott Laboratories, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, SmithKline Beecham, and Wyeth Ayerst Laboratories. Executives from a number of the pharmaceutical companies that manufactured antidepressants soon began showing up on the foundation’s board of directors, and as chairs of the organization’s annual fundraiser dinner.

Indeed, at this time, the Foundation regularly began collaborating with pharmaceutical companies to produce “educational” materials for the public and for medical professionals. In 1997, for example, the Foundation and Wyeth-Ayerst, the manufacturer of the antidepressant Effexor, jointly produced an educational video titled “The Suicidal Patient: Assessment and Care.” The video was designed to help “primary care physicians, mental health professionals, guidance counselors, employee assistance professionals, and clergy” recognize the warning signs of suicide, and help the suicidal person get the appropriate “treatment.” Shaffer was one of the experts featured in the film.

In subsequent years, pharmaceutical companies provided funding for the Foundation to conduct surveys, run screening projects, and support research. For example, in 2009, the Foundation reported that a new screening project had been made possible by “funding from Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Solvay, and Wyeth.” While most of the Foundation’s revenues today comes from its Out of the Darkness Community Awareness Walks, the Foundation’s leadership continues to feature a mix of academic psychiatrists and pharmaceutical executives.

The president of the board is Jerrold Rosenbaum, chair of the psychiatry department at Massachusetts General Hospital. In the early 1990s, while being paid as an advisor to Eli Lilly, Rosenbaum defended Prozac against claims that it could induce suicidal impulses in some patients. Other members of the board today include Mann, Nemeroff, and executives from Pfizer, Allergan, and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Allergan executive Jonathan Kellerman chaired the Foundation’s 2018 Lifesavers fundraiser, and the organizing committee included representatives from Lundbeck, Otsuka, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

Given this leadership, the Foundation’s “educational” efforts, which sought to shape public and professional thinking about suicide, were of the same kind that the American Psychiatric Association and pharmaceutical companies, with an assist from the NIMH, had created when Prozac came to market.

In a 1986 survey, the NIMH had found that only 12% of American adults would take a pill for depression. Seventy-eight percent said they would simply “live with it until it passed,” confident that with time, they could handle it on their own. However, shortly after Prozac came to market, the NIMH, with funding from pharmaceutical companies, launched a Depression Awareness and Recognition and Treatment campaign (DART), which was designed to change that public understanding. The American public was now informed that depression was a “disorder” that regularly went “underdiagnosed and undertreated,” and that it could “be a fatal disease” if left untreated. Antidepressants were said to produce recovery rates of “70% to 80% in comparison with 20% to 40% for placebo.”5

This was the soundbite message that the American Psychiatric Association (APA) promoted to the public. Antidepressants were said to fix a chemical imbalance in the brain that caused depression, and in the early 1990s, the APA began sponsoring a “National Depression Screening Day” to get more people into treatment.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, as it grew into a political force in the 1990s, sounded an almost identical message in its campaigns. It described suicide as a public health problem that regularly went “under-recognized” and it urged people who were feeling suicidal to “seek out a mental health professional,” with antidepressants a recommended treatment. “Research shows that depression is caused, at least in part, by changes in brain chemistry,” it stated on its website, at least up until 2015. “Antidepressant medications work to reset the brain, helping you to go back to feeling like yourself.”6

The APA was eager to tout its SSRIs as protective against suicide, and once the suicide rate began dropping in the 1990s, leaders in American psychiatry began to claim that the increasing use of these drugs was the cause of this drop. As a 2005 article in Psychiatric News reported, research had shown that “as prescribing of medications—especially newer antidepressants—increases, suicide rates go down.”

In a Powerpoint presentation that Mann gave in his capacity as Foundation president (2004 or later), he laid out this “antidepressants save lives” case, summarizing his argument in a few key bullet points:

- Most suicides occur in untreated depressed persons.

- Not treating depression may be lethal.

- The national suicide rate climbed 31% in the years 1957 to 1986, all prior to SSRIs.

- From 1985-1999, the US suicide rate declined 13.5% and antidepressant prescription rates increased over four-fold.

- For every “10% increase in the total antidepressant prescription rate, the national suicide rate decreased by 3%.”

- These findings indicate that untreated depression is the main cause of suicide and treatment can save a lot of lives.

His presentation told of the medicalization of suicide, with failure to get treatment a primary reason it could be fatal. As Mann said in a later interview, “Most suicides have an untreated mood disorder . . . Use of antidepressants to treat major depressive episodes is the single most effective suicide prevention measure in Western countries.”

The Foundation also promoted suicide screening efforts, and Shaffer, for his part, developed the “Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale,” which was said to “quantify the severity of suicidal ideation and behavior.” Today, the Foundation pushes an online “Interactive Screening Program” for use by colleges, law enforcement agencies and workplaces. The screening, the Foundation writes, “provides a safe and confidential way for individuals to take a brief screening for stress, depression, and other mental health conditions, and receive a personalized response from a caring mental health counselor.”

Perhaps the most important vehicle that the Foundation created to promote its message to the public—and to youth—has been its “Out of Darkness” walks, which now come in three flavors: community walks, campus walks, and overnight walks. The stated purpose of these walks is to get people to talk about suicide (e.g. bringing such impulses out of the darkness and into the light), and to raise funds for the organization. These walks have proven so successful that in 2017 they raised $22.7 million for the non-profit, which represented 90% of its revenues for that year.

The Out of Darkness campaign, developed while pharmaceutical company executives were on the Foundation’s board, reveals a certain Mad Men genius. They have relieved the pharmaceutical companies of a financial burden (light as it may have been for them), while providing the Foundation with the aura of a grass-roots organization. The Foundation’s annual Lifesavers dinner, which has long enjoyed the support of pharmaceutical companies, generated only $515,000 in 2017, a fraction of the Foundation’s total revenues. The pharmaceutical presence within the Foundation is now obscured, unless one takes the time to look at the bios of the board members and the list of pharmaceutical companies helping to organize and fund the annual Lifesavers dinner.

The importance of all this is to set forth a correlation timeline: It was in the late 1990s that the Foundation came to be led by academic psychiatrists and pharmaceutical company executives. The Foundation promoted a narrative that conceptualized suicide within a medical context, of a risk primarily for people with a mental disorder. The medical treatment of that disorder—with antidepressants as the first treatment of choice—was touted as a primary preventive measure. Yet suicide rates have risen since that time, which provides reason to ask whether this medicalized approach has been counterproductive.

A National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: 2000-2017

From its inception, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention sought to lobby the federal government to create a national suicide-prevention strategy, and in 1997, it could celebrate its success in this regard. Both houses of Congress passed resolutions declaring suicide a “national problem,” and that suicide prevention was a “national priority.” The House resolution declared that suicide prevention initiatives should include the “development of mental health services to enable all persons at risk for suicide to obtain services without fear of stigma.”

These resolutions led to the creation of a public-private partnership that sponsored a national consensus conference on this topic in Reno, Nevada, which is remembered today, according to a government paper, as the “founding event of the modern suicide prevention movement.” The wheels of government were now rolling, and in 1999, U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher issued a “Call to Action to Prevent Suicide,” which described suicide—even though suicide rates were hitting a 50-year low—as a “serious public health problem.” Next, Health and Human Services formed a group, composed of individuals and organizations from both the private and public sectors, to develop a “National Strategy for Suicide Prevention,” with this group finalizing its recommendations in 2001.

Since then, government agencies at all levels—federal, state, and local—have launched suicide prevention efforts. The federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Agency (SAMHSA) established a national network of crisis call centers, which is now called the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. The federal money began to flow, with SAMHSA administering grants to states, schools, non-profit organizations and businesses to develop suicide prevention campaigns. Research was funded to evaluate these efforts, with the thought that this would lead to “evidence based” practices.

Other non-profits have formed to combat suicide, and with suicide a regular topic of concern at local and national levels, a National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention was organized in 2010. Two years later, the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention was updated, with all of these efforts from the past decade proudly described in a paper titled “National Milestones in Suicide Prevention.”

Thus, we see in this brief history, a second correlation: The suicide rate in the United States has risen steadily since the creation of a national strategy to prevent it.

Psychiatric Care as a Risk Factor

The assumption with suicide prevention efforts is two-fold. One, that the screening programs and PR campaigns will help people who are feeling suicidal get help. Two, that mental health treatment will lower the risk that people struggling in this way will die by suicide.

There are three types of research that help assess whether public health approaches of this type—which ultimately treat it as a medical problem—are effective.

1. The efficacy of national mental health policies, programs, and legislation

In the early 1990s, the World Health Organization urged countries around the world to develop national mental health policies and legislation, and to improve their mental health services, with the expectation that doing so would lead to improved mental health outcomes. A reduction in suicide rates would be an expected marker of such improvement.

In 2004, Australian researchers, led by Philip Burgess, came up with a simple way of testing the efficacy of such national programs: they could assess suicide rates in countries pre- and post-implementation of these efforts. Their hypothesis, they wrote, was that the introduction of such programs “would be associated with lower national suicide rates.”

However, in their study of 100 countries, they found that, “contrary to the hypothesized relation,” the “introduction of a mental health policy and mental health legislation was associated with an increase in male and total suicide rates.” They even quantified the negative impact of specific initiatives:

- The adoption of mental health legislation was associated with a 10.6% increase in suicides.

- The adoption of a national mental health policy was associated with an 8.3% increase in suicides.

- The adoption of a therapeutic drugs policy designed to improve access to psychiatric medications was association with a 7% increase in suicides.

- The adoption of a national mental health program was associated with a 4.9% increase.

The one effort that produced a positive effect, they found, was the adoption of a substance abuse policy. “It is a concern,” the researchers concluded, “that national mental health initiatives are associated with an increase in suicide rates.”

Next, Ajit Shah and a team of UK researchers studied elderly suicide rates in multiple countries, and once again, the results confounded expectations. They found “higher rates (of suicide) in countries with greater provision of mental health services, including the number of psychiatric beds, psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses, and the availability of training mental health (programs) for primary care professionals.”

In 2010, Shah and colleagues reported on an expanded study of suicide rates, this time for people of all ages in 76 countries. They found that suicide rates were higher in countries with mental health legislation, just as Burgess had found. They also reported that there was a correlation between higher suicide rates and a higher number of psychiatric beds, psychiatrists, and psychiatric nurses; more training in mental health for primary care professionals; and greater spending on mental health as a percentage of total spending on health in the country.

Finally, in 2013, A.P. Rajkumar and colleagues in Denmark assessed the level of psychiatric services in 191 countries, with a “combined population” of more than 6 billion people. This was a comprehensive global study, and, once again, they found that “countries with better psychiatric services experience higher suicide rates.” Both the “number of mental health beds and the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population were significantly associated with higher national suicide rates (after adjusting for economic factors),” they wrote.

Four studies of mental health programs in countries around the world, and each study found, to one degree or another, that increases in mental health legislation, training, and services were associated with higher national suicide rates. Their study, Rajkumar and colleagues wrote, had confirmed the earlier studies, and they pointed to the medicalization of suicide as a likely causative factor.

“Reducing public health to a biomedical perspective is a common error in many low and middle-income countries. Attempts to reduce their national suicide rates are made by supplying antidepressants to peripheral health centres, while leaving daily miseries, such as poverty, lack of social security, poor sanitation, hunger and scarcity of water, unaddressed.” This “medicalization of suicide,” they continued, “underplays the importance of associated socio-economic factors. Medicalizing all human distress attempts to promote simplistic medical solutions to the problem of suicide.”

2. The risk of suicide in patients who get psychiatric treatment

People who seek psychiatric help are exposed to a sequence of possible events: diagnosis, drug treatment, regular contact with a mental health professional, treatment in a psychiatric emergency room, and becoming a hospital inpatient, with the latter possibly forced upon the person. In 2014, Danish investigators, led by Carsten Hjorthoj, determined that the risk of suicide increases dramatically with each increase in the “level of treatment.”

They found that, in comparison to age- and sex-matched controls who had no involvement with psychiatric care during the previous year, the risk of suicide was:

- 5.8 times higher for people receiving psychiatric medication (but no other care)

- 8.2 times higher for people having outpatient contact with a mental health professional

- 27.9 times higher for people having contact with a psychiatric emergency room

- 44.3 times higher for people admitted to a psychiatric hospital

While this steplike increase might be expected, given that the severity of patients’ struggles would likely be greater with each step up the treatment ladder, the researchers noted that the increased risk of suicide was particularly pronounced for married people, and for those with higher incomes or higher levels of education and no prior history of attempted suicide.

“The dose-response association between level of psychiatric treatment and risk of dying from suicide is steeper within the subgroups at relatively lower risk of suicide,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, two Australian experts in suicide asked the question that the researchers had skirted in their discussion: could psychiatric treatment, in some way, be toxic? The findings “raise the disturbing possibility that psychiatric care might, at least in part, cause suicide,” they wrote.

Even psychiatric inpatients deemed to be at a low risk of suicide had a suicide rate 67 times higher than the national suicide rate in Denmark, they noted.

“It would seem sensible, for example, all things being equal, to regard a non-depressed person undergoing psychiatric review in the emergency department as at far greater risk than a person with depression, who has only ever been treated in the community.”

Hospitalization, they added, could be particularly demoralizing.

“It is therefore entirely plausible that the stigma and trauma inherent in (particularly involuntary) psychiatric treatment might, in already vulnerable individuals, contribute to some suicides. We believe it is likely that a proportion of people who suicide during or after an admission to hospital do so because of factors inherent in that hospitalization . . . Perhaps some aspects of even outpatient psychiatric contact are suicidogenic. These strong stepwise associations urge that we pay closer attention to this troubling possibility.”

While the Danish study raised this “troubling possibility,” it lacked a necessary comparison group to investigate this worry any further. What were suicide rates for those with similar mental problems who didn’t get treatment? Were they higher? Or—and this would be the case if psychiatric care increased the risk of suicide—were they lower?

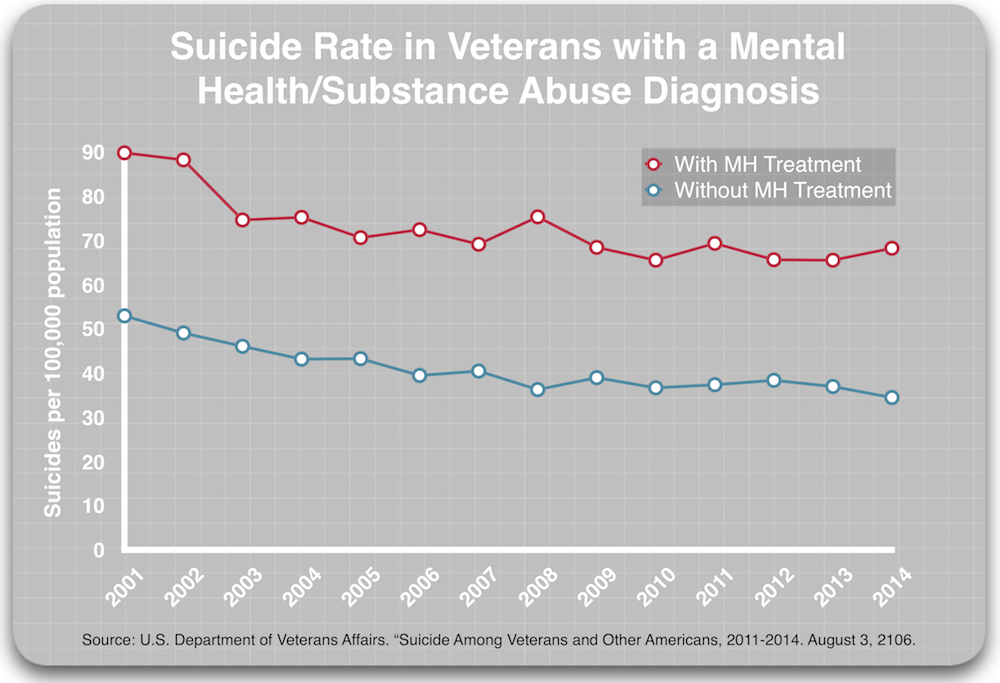

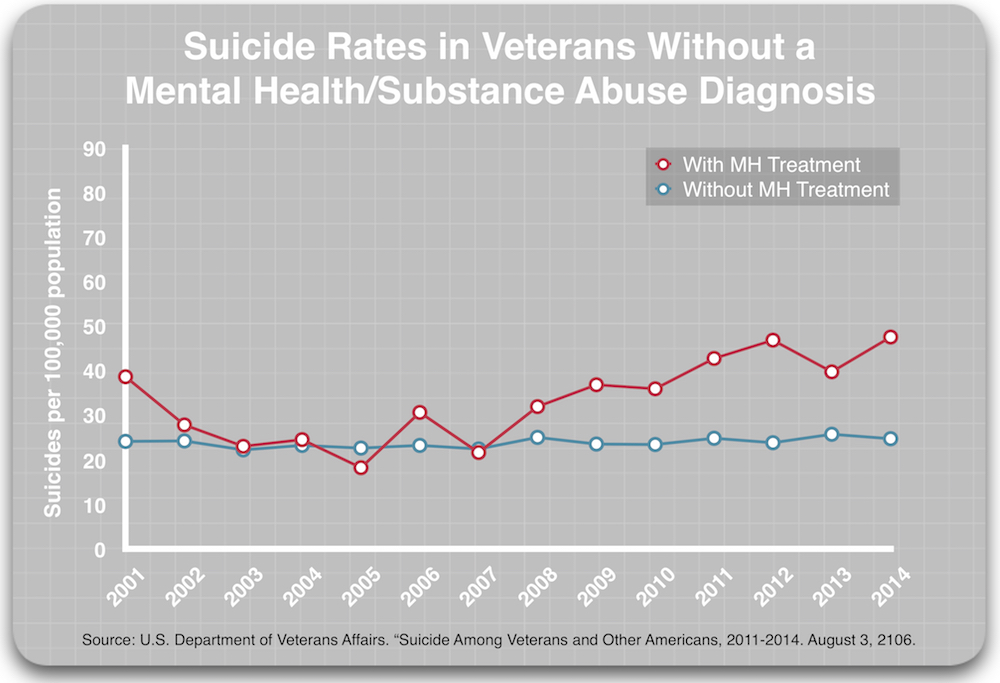

A 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Veterans provides such a comparison. The VA touted it as the “most comprehensive analysis of Veteran suicide in our nation’s history,” involving the examination of “more than 55 million records from 1979 to 2014 from all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and Washington D.C.” The report details suicide rates for veterans from 2001 to 2014, and there were two comparisons that are relevant to this question.

First, the report revealed that those with a mental health/substance abuse diagnosis who got mental health treatment were at least 50% more likely to die by suicide than those who had a diagnosis but did not access mental health treatment.

Second, the report revealed that among those without a diagnosis, those who got mental health treatment died by suicide at a higher rate than those who did not get such treatment.

In other words, in comparisons between veterans of similar diagnostic status (either diagnosed or not diagnosed), those who received mental health treatment suicided at a much higher rate.

3. The impact of antidepressants

The controversy over the impact of antidepressants on the suicide rate erupted in the early 1990s, and has been roiling ever since. Unfortunately, this controversy is often framed as a black-and-white debate—are the drugs protective against suicide, or do they increase the risk of suicide?—which muddles, to an extent, the relevant public health question.

There is clear evidence that SSRIs and other antidepressants can provoke suicidal impulses and acts in some users, and the reason why is well known. SSRIs and other antidepressants can stir extreme restlessness, agitation, insomnia, severe anxiety, mania and psychotic episodes. The agitation and anxiety, which is clinically described as akathisia, may reach “unbearable” levels, and akathisia is known to be associated with suicide and even homicide.

At the same time, there are many people who will tell of how SSRIs or some other antidepressant saved their lives, as their suicidal impulses waned after going on the drugs.

Thus, these drugs may induce mortal harm in some users, and be lifesavers for others. As such, the public health question is about the net effect of these drugs on suicide rates. Is the number of “saved lives” greater than the number of “lost lives?”

There are three types of evidence to be reviewed: randomized clinical trials of antidepressants, epidemiological studies, and ecological studies.

RCTs

Randomized clinical trials are seen as the “gold standard” in assessing the benefits and risks of a medical treatment, but the RCTs of SSRIs and other novel antidepressants, in terms of assessing suicide risks, were compromised in multiple ways: most were financed by pharmaceutical companies; the trials excluded people who were suicidal; they employed “washout” designs such that the placebo groups are more aptly described as drug-withdrawn groups; and there was corruption in the reporting of suicides.

The corruption aspect reared its ugly head in the trials of the first SSRI to be approved for marketing, Prozac. As civil court cases later revealed, Eli Lilly recoded suicidal events in the group treated with Prozac as “emotional lability,” thereby hiding the evidence of the suicide risk in the data submitted to the FDA. As other SSRIs were brought to market and tested for use in adolescents, other documented accounts of the companies’ hiding suicides emerged. In addition to the re-labeling shenanigans that Eli Lilly employed, several pharmaceutical companies attributed suicides that occurred during the washout period, before randomization, to the placebo group, thereby inflating the reported risk of suicide in that cohort.

Here is how Peter Gøtzsche, director of the Nordic Cochrane Center, describes this evidence base: “There has been massive underreporting and even fraud in the reporting of suicides, attempts and suicidal thoughts in the placebo-controlled trials. The US Food and Drug Administration has contributed to the obscurity by downplaying the problems, by choosing to trust the drug companies, by suppressing important information, and by other means.”

Even so, it is the FDA’s review of this evidence base that has informed societal thinking about the suicide risk with SSRIs, and so this is where any review of the impact of antidepressants on suicide needs to start. The FDA has concluded that, in the industry-funded trials, antidepressants were shown to increase the risk of suicidal thinking for those under 25; had a neutral effect on those 25 to 64; and were protective against suicidal thinking for those over 64.

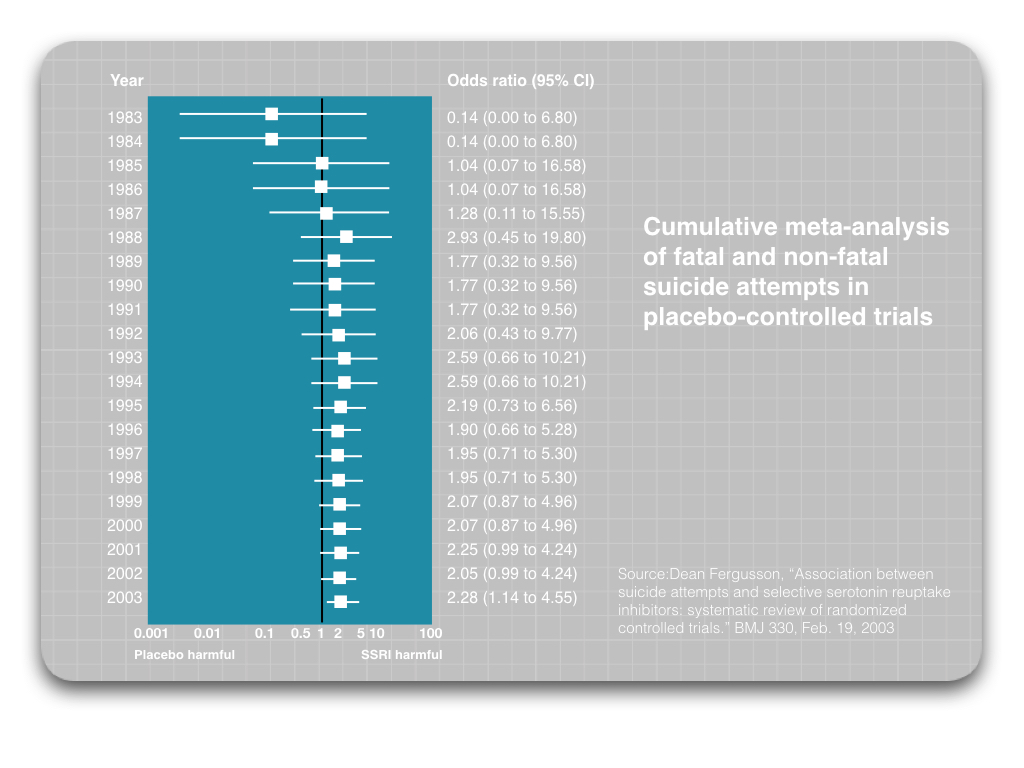

However, there are other reviews of RCTs of SSRIs that have come to a different conclusion. In 2003, UK psychiatrist David Healy and his colleague Chris Whitaker reanalyzed the published results for five SSRIs. They identified suicides that had occurred during the washout period that had been wrongfully attributed to the placebo group, and after removing those suicides, they concluded that the SSRI groups were more than twice as likely to commit suicide (or to attempt suicide).

Next, Healy and a team of Canadian scientists conducted a meta-analysis of all RCTs of SSRIs, which incorporated findings from a number of studies that weren’t funded by pharmaceutical companies. They identified 702 studies that provided useful data, and determined that suicide attempts were 2.28 times higher for those treated with an SSRI compared to placebo. Moreover, in a year-by-year meta-analysis of published studies, the rate of suicide attempts in the SSRI group was higher than in the placebo group every year from 1988 through 2003.

More recently, Peter Gøtzsche and colleagues from the Nordic Cochrane Center conducted an analysis of 64,381 pages of clinical study reports that came from 70 trials of antidepressants, which they solicited from the European Medicines Agency. They determined that in adults, antidepressants doubled the risk of suffering akathisia, a risk factor for suicide. In a subsequent study, Gøtzsche and colleagues found that in adult healthy volunteers, antidepressants similarly “double the occurrence of events that the FDA has defined as possible precursors to suicide and violence.”

Thus, the conclusion to be drawn from RCTs could be said to be of two kinds. If the data submitted by the drug companies is taken at face value, SSRIs and other new antidepressants that have come to market since 1987 may raise the risk of suicide in those 25 and under, but otherwise are either neutral or protective in older age groups. However, if there is an effort to account for some of the corruption in the RCT literature, it appears that SSRIs may double the risk of suicide attempts and dying by suicide.

Epidemiological studies

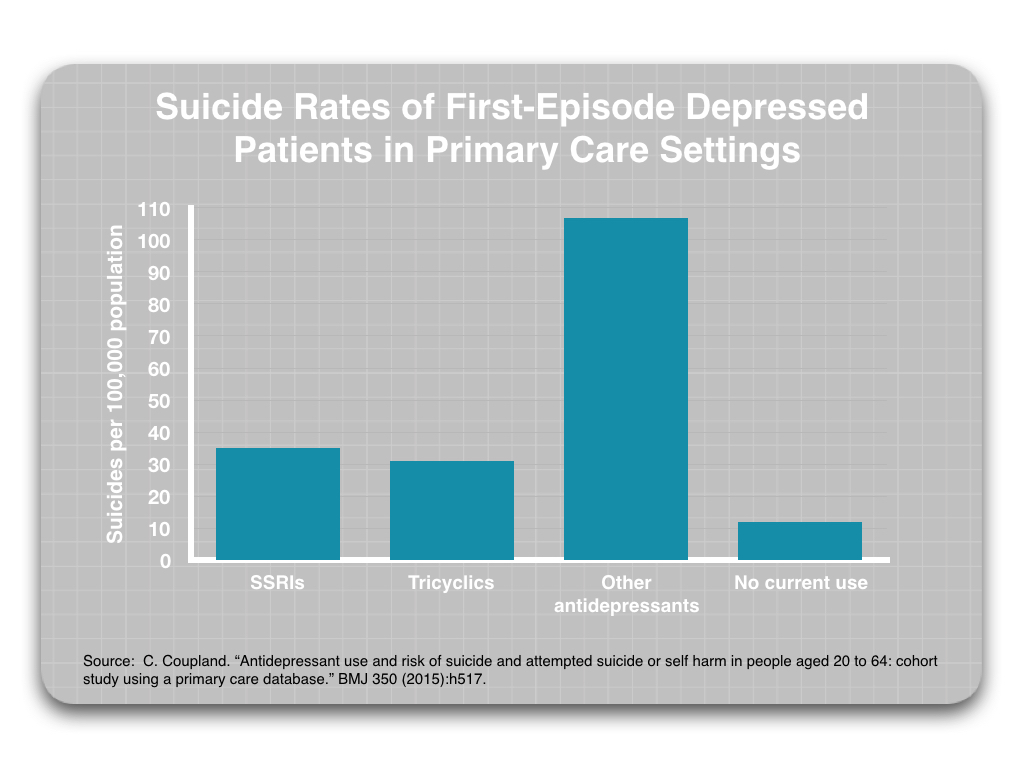

The industry-funded RCTs mostly evaluate suicide risks in a select group of patients: those with moderate to severe depression who are not suicidal at the outset of the trial. But most of the prescribing of antidepressants occurs in outpatient settings, and often in primary care. Epidemiological “case-control” studies can provide some insight into whether antidepressants increase the risk of suicide in this group of patients.

In 1998, Gregory Simon and colleagues reported on suicides among 35,546 people in the Puget Sound area of Washington who were treated for depression, and found that the risk of suicide was 43 per 100,000 person years for those treated with an antidepressant in primary care, compared to zero per 100,000 person years for those treated in primary care without antidepressants.

Next, in 2003, Healy and Chris Whitaker analyzed suicide data reported for primary care patients with an affective disorder in the UK, and, after reviewing various sources of data, concluded that the rate for those taking an SSRI was 3.4 times greater than for those treated with “non-SSRI antidepressants or even non-treatment.”

A large study in British Columbia, while not providing any info about a non-medicated group of patients, also found a high suicide rate among users of antidepressants in the general population. They studied 247,583 adults who began taking an antidepressant between 1997 and 2005 and reported a suicide rate of 74 per 100,000 person years in that period. This is similar to the suicide rate in the VA study for those with a diagnosis who got mental health treatment.

Finally, researchers in the UK studied a cohort of 238,963 patients aged 24 to 64 who experienced a first episode of depression between 2000 and 2011, and they found that such patients were at particularly high risk of suicide during the first four weeks after starting an antidepressant and then again during the four weeks after stopping the drug. They also reported that suicide attempts and completed suicides were more than 50% lower for periods when patients weren’t currently using an antidepressant compared to when they were taking one.

These epidemiological studies, which are designed to provide insight into what happens to patients treated in primary care settings, all point to a conclusion that drug treatment elevates the risk of suicide, and that is particularly true when they first start taking such a drug, and when they stop doing so.

However, there is one large epidemiological study of severely depressed patients that found suicide rates that reflect the FDA’s black box warning on these drugs. In a study of Medicaid patients from all 50 states who received inpatient treatment for depression, David Shaffer and colleagues found that there was no significant association between antidepressant usage—positive or negative—on suicide rates for those 19 to 64 years old, but that there was a significant increase in suicide attempts and completed suicides among children and adolescents (aged 6 to 18 years) who took the drugs.

Ecological Studies

Ecological studies assess suicide trends in countries as their usage of antidepressants changes, and this is the correlational evidence cited by Mann and others in American psychiatry as proof, when suicide rates in the United States fell from 1987 to 2000, that the new SSRIs were protective against suicide. There have been similar reports about dropping suicide rates in European countries as usage of antidepressants has risen, and even today, these ecological studies remain the primary “evidence base” for claims that antidepressants are protective against suicide.

However, while there are studies that show this correlation, there are also studies that do not. In a 2007 review of 19 ecological studies, Ross Baldessarini and colleagues concluded that eight show a positive correlation between increased antidepressant use and decreased suicide rate; three found a correlation but the decrease in suicide predated the increase in the use of antidepressants; five studies were inconclusive as to whether there was any correlation; and two were negative, finding a correlation between increased use of the drugs and an increase in suicide. Furthermore, during the 1990s, while suicide rates decreased in 42 of 79 countries, they either increased or there was no change in the remaining 37.

“Evidence of specific antisuicidal effects of antidepressant treatment from ecological analyses remains elusive,” the researchers concluded.

Meanwhile, in the United States, suicide rates have steadily increased since 2000, which has been a time of increasing use of antidepressants. The correlation has gone the wrong way in this country for 16 years.

Summing Up the Evidence

The question being raised in this report is whether there is reason to believe that medicalizing suicide, with antidepressants recommended as a first-line treatment for depression, is counterproductive, and serves as a “risk factor” that, if all other things are equal, could be expected to lead to an increase in the national suicide rate. And here is what the three lines of evidence reviewed here revealed:

- The adoption of mental health programs in countries around the world was associated with an increase in national suicide rates.

- Research has shown that the risk of suicide increases with each increase in the level of treatment.

- The large VA study found higher suicide rates in those patients who accessed mental health treatment than those who did not (in both diagnosed and non-diagnosed groups).

- When the RCT data is adjusted for misattribution of suicides to the placebo group, or case report forms are analyzed, it tells of antidepressant drug therapy that increases the risk of suicide and suicide attempts.

- Epidemiological studies of primary care patients show higher suicide rates in those treated with antidepressants, with this suicide risk particularly acute during times of drug initiation and drug withdrawal.

- A large epidemiological study of severely depressed children and adults found that the risk of dying by suicide was significantly higher for children and adolescents who took antidepressants, but that there was not an elevated risk for those 19 and over.

Reviewers of an “evidence base” for any question may come to different conclusions about what it all means. Those invested in the conventional wisdom will undoubtedly find reasons to dismiss the research reviewed here as flawed, unconvincing, and so forth. But, in terms of providing research findings that can inform a larger societal debate, it is possible to clearly see that there is an argument to be made: There is a body of collective evidence that mental health care, when it focuses on treatment with antidepressants, raises the risk of suicide at a general population level.

The Increase in Antidepressant Use, 2000-2014

Much as it was possible to calculate the effects that changes in household gun ownership and unemployment could be expected to have on suicide rates, it is possible to calculate, based on the VA report cited above, the theoretical effect that increased access to mental health treatment could be expected to have, with antidepressant usage serving as a marker for increased access to treatment.

According to the latest report from the Centers for Disease Control, antidepressant usage in the population aged 12 and over increased from 7.7% in the 1999-2003 period to 12.7% in 2011-2014. This increase in antidepressant usages exposes an additional 5% of the population to mental health treatment, and based on the VA data on the variable suicide rates for veterans with a mental health diagnosis, depending on whether they are getting “mental health” treatment, this could be expected to produce an increase in suicides of 1.6 per 100,000 population. (See calculation7)

During this period (2000 to 2014), the suicide rate increased from 10.5 per 100,000 to 12.6 per 100,000. The increased antidepressant exposure could account for 75% of this hike, with all other things being equal.

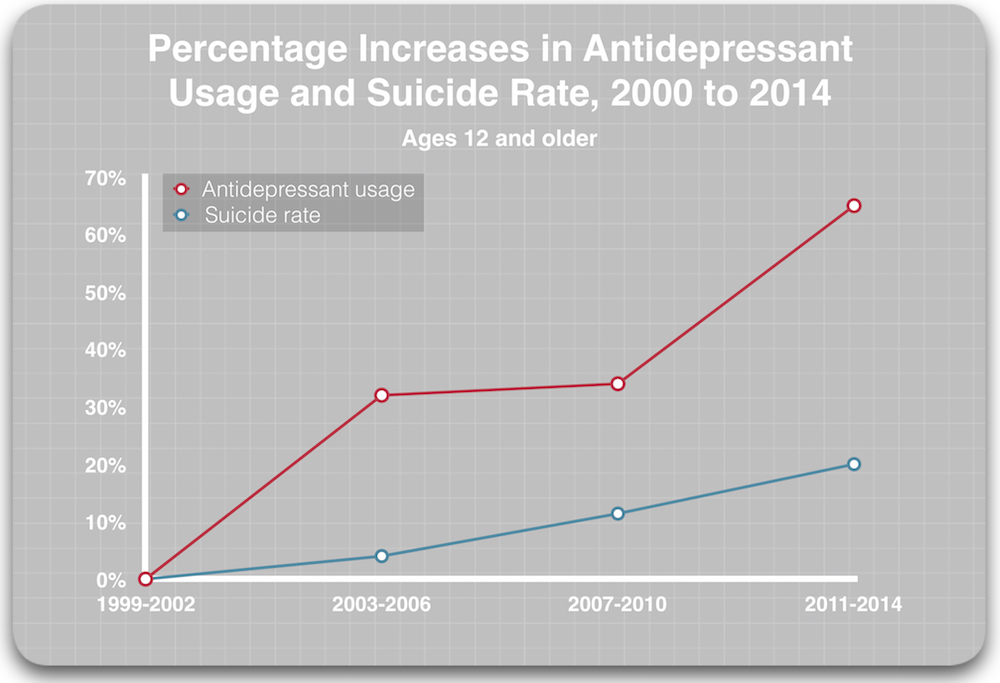

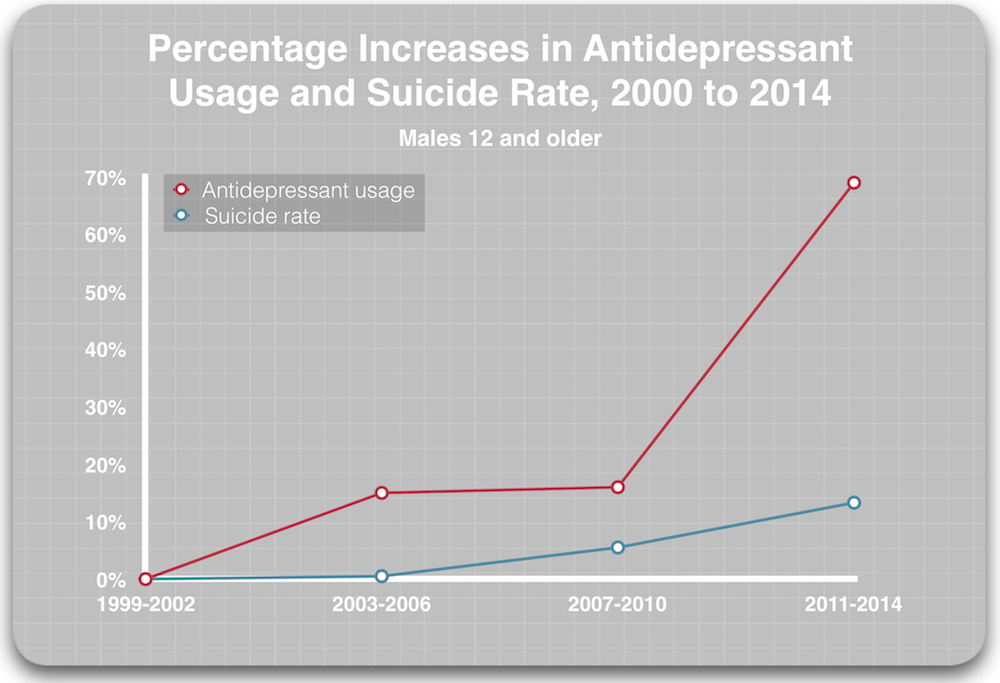

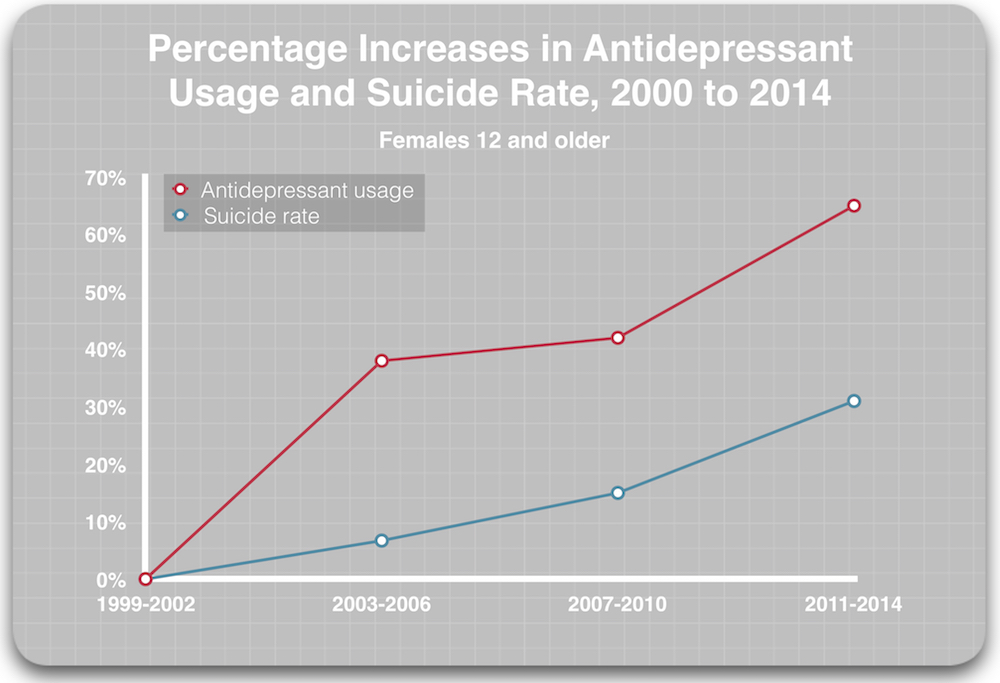

Another way to visualize this correlation between antidepressant usage and rising suicide rates is to graph the percentage increases in antidepressant usage and suicide rates over this time.

As is often noted, “correlation is not causation.” But this is correlative data of a different sort: The research findings on mental health care and antidepressants leads to an expectation that rising antidepressant usage will have a negative impact on the national suicide rate. As such, this is a correlation supported by “causative” research findings.

The reasons for the negative impact of mental health treatment on suicide rates may be many: the stigma associated with getting diagnosed; the internalization of the idea that one’s brain is “broken; the trauma of hospitalization (and particularly of forced hospitalization); and for some, antidepressant-induced akathisia. The studies cited in this paper touch on all these possibilities.

Rethinking Suicide Prevention

The Prozac era, once heralded as a great scientific advance, has turned into a bust in so many ways. Mood disorders today exact much more of a toll on our society than they did in 1987, with soaring disability numbers due to mood disorders one example of that toll. The rising suicide numbers are more evidence, tragic in kind, of the failure of that vaunted “revolution” in psychiatric drugs.

It was an alliance of pharmaceutical companies, the American Psychiatric Association, and academic psychiatrists that sold the American public on the wonders of SSRIs and other new antidepressants, and there is a similar alliance that shaped our thinking about suicide. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, once it came under the influence of academic psychiatrists and pharmaceutical companies, told of how untreated mood disorders were a primary cause of suicide, and that people with suicidal thoughts needed to hurry into treatment.

This was a message that capitalized on societal concern about suicide and turned it into one that further built the market for these drugs. For a time, up until 2000, the Foundation and American psychiatry could cite the dropping suicide rate as correlative evidence of the suicide-protective benefits of SSRIs, and yet when the suicide rate began to climb, this alliance didn’t miss a beat, and instead turned the findings into an alarm about a hidden “epidemic” in our midst. And the cause of this epidemic? There were so many people failing to get helpful antidepressant treatment for their mental disorders.

Yet, all along, there was a lack of evidence that increased access to psychiatric care reduced suicide, or that treatment with an antidepressant lowered the risk of suicide. Instead, there was a growing body of evidence that this medicalized approach to suicide could make things worse.

Indeed, there are many people who have written blogs on Mad in America telling of how they first became suicidal after getting into treatment.

That is the public health tragedy: our society organized its thinking about how to “prevent suicide” around a story that served commercial and guild interests, rather than around scientific findings, which time and again served as warning signals about this medicalized approach.

There are obvious practical steps that our society could take to reduce our suicide rate. Promoting safe gun storage is one; reducing access to other means of suicide is a second. Denmark, which had an extraordinarily high suicide rate in the 1970s, adopted this approach, limiting access to barbiturates and reducing carbon monoxide from household gases, and it now has one of the lower suicide rates in Europe.

Beyond such efforts, what is needed today is a new conceptualization of suicide, and how to respond to it. Perhaps what is needed is a conceptualization that sees suicide as mostly arising within a social context, and so what is needed is a response that provides community and a greater respect for the autonomy of the person who is feeling suicidal. That person is still the director of his or her own life, and forced hospitalization, in particular, may rob a person of that cherished sense of self.

There are peer-led groups striving to reconceptualize suicide in this way. The Western Massachusetts Recovery Learning Center has developed a program it calls “Alternatives to Suicide,” and it takes a very different, non-medical approach to helping someone struggling with despair and pain.

These are “lights,” it seems, that could lead our society “Out of Darkness,” and help put our national suicide rate on a different trajectory than the one it has been on for the past 17 years.

Sources:

- Centers for Disease Control, National Vital Statistics, Mortality. Age-adjusted death rates for approximately 64 selective causes, by race and sex: United States. Reports for the years 1950-59; 1960-67; 1968-78; 1979-1998. For years 1999-2017, see NCHS Data Brief, ibid.

- Bureau of Labor statistics, 1947 to 2017. (See BLS.gov).

- Calculations: If the suicide rate is three times higher for homes with gun ownership, this leads—given the overall rate of 12.8 per 100,000 in 1987- to an estimate of a rate of 20 per 100,000 for homes with a firearm, and a rate of 6.7 per 100,000 for those without a firearm. Thus, the calculation for 1987: 46% x 20 per 100,000 = 9.2 deaths; 54% x 6.7 per 100,000 = 3.6 deaths; total of 12.8 per 100,000. In 2000, the new calculation would be: 32% x 20 per 100,000 = 6.4 deaths; 68% x 6.7 per 100,000 = 4.6 deaths; total of 11.0 per 100,000.

- PR Newswire, “The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention announced today the appointment of two prominent Atlantans to its Board of Directors.” December 2, 1997.

- Robert Whitaker, Anatomy of an Epidemic (New York: Crown, 2010) 289-91.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention website: Accessed on October 6, 2015. This chemical imbalance claim appears to have been dropped from the website by 2018.

- The suicide rate in the VA study for those with a diagnosis who didn’t access mental health treatment, averaged, over the 14-year period, 40.9 per 100,000. The average rate for those with a diagnosis who accessed mental health treatment was 72.7 per 100,000 (31.8 per 100,000 higher). With 5% of the population moving from this lower risk to the higher risk group, this would produce an increase in suicides of 31.8 x .05, or 1.6 per 100,000.

An outstanding overview. thank you.

Report comment

For a UK view this report on suicide and economic factors by Samaritans is illuminating https://www.samaritans.org/sites/default/files/kcfinder/files/Samaritans%20Dying%20from%20inequality%20report%20-%20summary.pdf

Report comment

From The Irish Samaritans

https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://www.samaritans.org/sites/default/files/kcfinder/files/press/Irish%2520Media%2520Guidelines%25202009.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwit_ojR2tvcAhWjT98KHSFsA5QQFjAHegQIARAB&usg=AOvVaw17j6cgq7v42j-pP-Vya2K6

Within the subject of Murder Suicide “medication” is not mentioned which (as someone who has experienced Acute Akathisia) I believe should be.

“…Among the reasons for murder-suicide are

morbid jealousy, family, financial and social stressors, retaliation or revenge, mercy killing because of declining health, salvation fantasies, rescue and escape from problems. Mental illness, alcohol and drug abuse, with their attendant problems, are a major factor in many of these tragedies.

Family break up and disputes over custody of the children are the driving force in many murder-suicides…”

These tragedies are very real but can be avoided.

Report comment

Thank you very much.

Report comment

Thank you, Robert, for this review. I saw one, what I’m pretty certain was an error, that you may want to correct or clarify.

“In 2003, at the request of Pfizer, he sent a letter to the British drug industry stating that there was insufficient evidence to restrict the use of SSRIs in adolescents, even though the FDA, after reviewing the clinical trials of SSRIs in those under 18 years of age, had put a “black box” warning on the drugs, telling of how they doubled the risk of suicidal thinking in this age group.”

I’m pretty certain the black box warning was not put on the antidepressants until 2004.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health/antidepressant-medications-for-children-and-adolescents-information-for-parents-and-caregivers.shtml

But again, thank you for speaking out about the dangers of the antidepressants, including people of all ages, in such a straight forward and honest manner.

Report comment

As usual, very clear and well researched article from you, Bob.

There are so many ways that the medical model can make people suicidal.

1. You feel horrible and you are told this is because there is something wrong with your brain. You check with google about the chances of getting better, and you find the words “Chronic”, “recurrent” and “lifetime” associated with your diagnosis. You may then very easily conclude that you cannot live like this.

2. You get drugs that make you feel horrible, including losing sex drive, having numb genitals, strange aggressive thoughts, nausea, fatigue, sleeplessness, and inner torture (akathesia). You may think this means you are getting worse, and combined with point 1 above may decide that a life like this is not worth living.

3. If you correctly attribute the above to drug effects, you may think that you cannot live if you have to take drugs that make you so sick.

4. You may have thought of suicide already but care so much for those who love you, that you have decided to not go through with it. Then the drugs suddenly take away your feelings, and you are able to go through with your plans.

5. You feel that you are a burden to your loved ones when you are depressed, and then the diagnosis and googling makes you believe that you will be a permanent burden for them. The logical conclusion will then be to kill yourself to relieve them from this permanent burden.

Instead a good doctor or therapist should inform you that depression is not a disease, that it is in no way permanent, that it will most likely pass by itself, but that with therapy an paying attention to what made you sad ( e.g a n unhealty relationship) you can get rid of it faster, become less suicidal and be better protected against relapse, even though the risk of relapse unless you are treated with drugs is only 15%.

Report comment

@researcher: Some good points on how MH services can increase your suicidality.

Your point 1 is the killer. You thought they could make you feel better and they don’t . In fact they seem to panic, then they tell you you are distorted and disordered.

I wonder if I could add a couple of points.

1. They tell you the meds will fix your thinking and you feel devastated and doubly abnormal when they don’t. If you are untreatable there must be no hope…..

2. You do what they say and they threaten to imprison you. They even say “taking your life is not a decision we can let you make”. Your ultimate independent decision is about to be taken from you….

3. They tell you your progress is crap. Your prognosis must be bleak….

4. They tell you that you cannot fix this yourself, that you need medication. They flip flop and change doses and medication so often that there must be a problem. It’s not working…..

5. They make no effort to reintegrate you socially, we have to fix your brain first. They are not helping me get back to normal because they know it’s not possible. You sit at home late at night waiting for your brain to fix….

7. They say it’s an illness, an imbalance , that only the drugs can correct. So either I’m on meds for life to keep me balanced and the ‘illness” at bay, or I can never function again. Or……

As you say , researcher, how about some hope, belief, reassurance, experience, validation, wisdom, understanding.

You feel gloomy enough without more doom and gloom from the so called professionals.

If you go down their route, you will wake up 4 years hence from your zombified state, and feel your life chances have been further hit by being zonked for so long. And you won’t feel very good about that….

And yet there are psychosocial approaches that work, they are happening and they are real.

Report comment

Depression is about the easiest thing to “fix”. Just 20 minutes exercise 3 times pr week gives better results than Zoloft. Add a little bit of hope, better diet, some mindfulness, positive focus and research shows you have a good chance of getting better within s few months.

Those who laugh at these simple suggestions are usually talking about the artificial depression induced by antidepressants.

Report comment

Or are those who are making money off of selling them.

Report comment

Your list of “simple suggestions” is accurate although the social environment, both micro & macro, makes it often hard to implement. But accurate, yes.

Report comment

Spot on with this list. Time also heals. Or buy a Harley and ride.

Report comment

Devastatingly true analysis. Sometimes the story they want you to believe is even worse than the drugs!

Report comment

I know this sounds weird, but believing in my diagnostic label made me act crazier than ever. I would study the symptoms of said “illness” and–not fully consciously–excuse these bizarre, out of control behaviors on the grounds that I couldn’t control myself.

My frequent reason for thinking of killing myself was a fear of morphing into a monster because I couldn’t get my “meds” or they quit working. Like the end of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde where the poor doctor sits alone in his office all the time mixing and drinking the formula to keep his dark side at bay. Psychiatry has taken the premise of a dark fantasy novel and passed it off as hard science.

Report comment

Not weird at all. I’ve seen it happen.

Report comment

Dr.David Healy has a very good website rxisk.org discussing side effects to drugs. One very serious side effect of antidepressants is permanent sexual numbing, that doesn’t go away even if you stop the drug. Many other horrible side effects may also never go away. And young people are exposed to this by taking a drug that scientifically has been proven to not have an effect!!

This is also a side effect of acne and hair loss drugs.

Report comment

Dr. David Healy also thinks ECT is safe and effective (for severe depression, I’m not sure if he only advocates it for that). It’s definitely effective (sarcasm), according to ECT promotion websites 10% have significant memory impairment. That’s probably a very optimistic statistic.

I had a friend (when I was young) who had severe acne, as he was rich he had a specialist to treat his acne. You can’t imagine how sexually active he was. He was the gossip of the school. Maybe he was in denial (joke).

Report comment

I agree that Healy is a bit stubborn when it comes to ECT. ECT is probably the worst treatment of all but with an extreme placebo effect and enormous cognitive dissonance both for doctors and patients.

Report comment

More than “a bit stubborn”. Healy absolutely in denial and suffering from cognitive dissonance. How one can be so busy trying to point out the harms caused by drugs, and so concerned about sexual dysfunction, but blind to the damages caused by shock. Ppl injured by shock, losing decades of memories and losses of up to 30 IQ points, often end their lives.

Report comment

SSRI, acne and hair loss treatment can also give Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder, which sounds nice but which us described as hell on earth by those afflicted. And the arousal can be permanent even after treatment is stopped.

Report comment

Makes you wonder if these people are scientists, or mad scientists.

Report comment

Mad scientists is a great job title for them. 😀

They claim to treat the mad after all. Lol.

Report comment

ECT can be life saving in some instances. One of my patients had catatonia associated with starvation ketosis. She had a history of Bipolar Disorder and had stopped taking her medications prior to her admission. She did not respond to the ativan so after three courses of ECT, she finally started eating. It took another three weeks of inpatient treatment with pharmacotherapy to stabilizer her. Without ECT she would have had to have a PEG tube (feeding tube) surgically inserted in her stomach. ECT does have side effects but it is a highly effective treatment. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4473490/

Report comment

Thank-you for that very singular, anecdotal, and extreme report.

Wouldn’t you estimate that “can be life saving in some instances” works out to AT MOST 5% of persons currently victimized by Electro-Cution Torture? 1%? Also, “history of bipolar disorder” is equivalent to “got lots of presents from Santa Claus last Christmas”. Exactly *WHAT* “medications” had she stopped taking? How long had she been on them? What *in utero* alcohol/drug exposure did she have? Fetal & childhood nutrition? What’s her ACE profile look like?

If you’re going to come on MiA and defend Electro-Cution Torture, you need much better evidence. And just WHAT does a “positive” “response” to Ativan look like?

The death penalty does have side effects, but when used properly, it is 100% effective in preventing convicted murderers from re-offending.

ECT is nothing more than a non-lethal living death penalty.

ECT = Electro-Cution Torture

What kind of SICK SOCIETY produces people who need ECT in the first place?

RSVP?

Report comment

Ativan and similar drugs mess up your appetite too. Usually they make you blow up like a blimp overnight. Sometimes they cause loss of appetite at first though.

Being scared by your surroundings also makes you too sick to eat. And note how he credits the random brain damage with her eating again? It may have been she would have eaten again without having her brain assaulted.

Never been shocked myself. But I’ll take the words of those who have survived the ordeal over those who get paid handsomely to perform it. These scientists rhapsodize over how docile and (mindlessly) obedient the subject becomes, and let the released subject enjoy the brain damage at their leisure for the following decades.

Report comment

pro-mentalhealth – Well it sounds to me like your patient may have been in Full-blown withdrawal from stopping her medication when admitted. Did you re-instate the drug she stopped taking or just give Ativan which seems the standard drug in ALL the psychiatric hospitals and emergency rooms. While enduring mental tortures from my cold-turkey benzo & SSRI withdrawals Ativan was the ONLY drug given in ER and 2 trips to the psychiatric hospital, and whereas it put my withdrawals into somewhat remission, once released from the hospital and back home the drug wore off I was right back in terror, seizure, psychosis land from my withdrawals. But you jumped from Ativan directly to ECT’s! With all due respect to you, I’m glad I’m not your patient.

Report comment

Never having been suicidal myself (except in those few moments of extreme duress when hearing voices that wouldn’t stop, day after day, hour after hour, minute by minute) my principal concern is psychosis, not depression or suicide. Yet the whole question involved in any of these is the effects of modern “treatment” modalities, including drugs, and it has been an eye-opening experience for me to learn about the increased violence and suicidality associated with modern antidepressants. Your report greatly deepens that knowledge. Thank you.

Report comment

I wonder also how a refocusing of attention away from external environmental factors and toward brain chemistry manipulation contributes to people losing hope and increasing self-blame for their “condition.” Perhaps it’s easier not to feel hopeless if you can find an external condition that you CAN change and focus your energy on regaining control in that area. I’ve found that the most helpful thing for people who are feeling depressed is acknowledging that their feelings are a normal or at least not unusual reaction to the conditions of their life, and then focusing on one aspect of their lives, no matter how small, that they can exert some control over. Suggesting that “it’s all in your brain” may create a sense of hopelessness, as what can one do about one’s own brain chemistry?

Of course, there really ARE things one can do about one’s own brain chemistry, but that’s material for a different blog.

Report comment

So true !

Report comment

“I wonder also how a refocusing of attention away from external environmental factors and toward brain chemistry manipulation contributes to people losing hope and increasing self-blame for their ‘condition.'”

I personally found this tactic of today’s “mental health professionals” to be their goal, since I dealt with “mental health professionals” who chose to profiteer off of covering up the rape of my child as their initial, and end goal, according to all my family’s medical records.

But I will point out that this tactic of “refocusing of attention away from external environmental factors and toward brain chemistry manipulation,” then massively poisoning a person, which is being perpetrated against innocent humans by today’s “mental health professionals.” This is also known as gas lighting a person, which is a known form of mental abuse by today’s “mental health professionals,” NOT “mental health care.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaslighting

And turning child abuse victims into the “mentally ill” with the psychiatric drugs, is the number one actual function of today’s “mental health professionals,” according to their own medical literature.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

The ADHD drugs and antidepressants can create the “bipolar” symptoms, and these have been misdiagnosed as “bipolar” on a staggering scale in the USA.

https://www.alternet.org/story/146659/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america

And the “bipolar” and “schizophrenia” drugs, the neuroleptics (aka antipsychotics), create both the negative and positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via both neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome and antipsychotic induced anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

But since none of these medically known psychiatric drug induced toxidrome/syndrome are listed in the DSM, they are ALWAYS misdiagnosed by the doctors and “mental health professionals.”

Deluding today’s “mental health professionals” in this manner has no doubt resulted in a massive in scale, multibillion dollar, primarily child covering up, “mental health industry,” according to their own medical literature. Especially since NO “mental health professional” may EVER bill ANY insurance company for EVER helping ANY child abuse victim EVER, without first MISDIAGNOSING them with one of the billable DSM disorders.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Should covering up child abuse actually be the primary paternalistic actual function of today’s “mental health professionals?” Or is it time to get rid of the scientifically “invalid” DSM, that has turned our country’s “mental health professionals” into highly delusional, primarily pedophilia covering up, people?

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

Report comment

@Steve; The psychiatrist will say , seductively and rather insidiously “it’s frustrating for the patient to be encouraged to build their confidence and self esteem, because they will just feel that they are failing”.

Instead, the answer is to accept your illness, your faulty brain chemistry, and let me treat it. In other words, it’s not just that you are failing, it’s that you have no hope of success without me. Empowering!

Quite the contrary. For what it’s worth, I have a feeling that exercising extreme independence and control, “doing really hard things yourself, unaided” is key.

Report comment

Right, we wouldn’t want people trying things and not always succeeding – it will torpedo their self esteem! The proper action is to discourage them from trying anything at all by telling them they are incapable of both the action they want to AND of handling the disappointment if they are unsuccessful. THAT is a SURE way to make someone feel good about themselves!

Seriously, if you wanted to make someone feel as bad about themselves as you can, it would be hard to imagine a more effective course of doing so than telling someone they can’t handle trying something they are not assured of succeeding at. It makes me wonder how “accidental” this approach could be. It’s pretty freakin’ evil!

Report comment

@Steve: I know, it seems so debilitating because it appears so compassionate – “….you just feel like you’re failing. It’s trying to lift weights without the use of the arm”. So now the “illness” is being equated to amputation. And you know what’s coming next “but the good thing is, the imbalance is treatable…”

It’s one of the many things I look back at and think – did I really hear that?

And I think a lot about kids still inside waiting for the use of their “arm” to return.

Report comment

Very well put!

Report comment

Well said. If we looked at environmental factors, we may then have to challenge all systems. And who has the time for that?

Report comment

Besides which, it could cost some people BIG money!

Report comment

This is a great article.

Those who understand the true history of psychiatry know that psychiatry has been causing casualties ever since its inception. Psychiatry produces homicides and suicides while pretending to offer the cure. It is a nefarious and pseudo-scientific system of slavery. The abolition of psychiatry, like the abolition of chattel slavery, or the defeat of Naziism, is a moral imperative.

Those who are interested in discovering the truth about psychiatry will benefit from the following web site:

https://psychiatricsurvivors.wordpress.com/2016/05/10/the-truth-about-psychiatry/

Report comment

I just saw today on medscape a paper presented at this years APA conference. Apparently Doctors have the highest rate of suicide of any profession, double the rate of the general population. And (you’ve guessed it), of all the medical specialities, psychiatry is “near the top of the list”. Just the guys to help you in a crisis!

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/896257

Report comment

I think doctors are at a higher risk because they are often perfectionists and ultra competitive. Inevitably, when they can’t “fix” people they try to help, they feel like a failure. I also think that depression is quite high in this group. They are very intelligent academically, but often socially and personally they struggle.

Report comment

Its more than that.

Psychiatry attracts people who struggle with their own demons, but it is a profession that dehumanises people who struggle. People working in it have a choice of cutting off from their vulnerability, or being ostracised.

Report comment

That is exactly how I experienced it. I held to my integrity as best I could, but it was not safe to talk about certain things, and certainly not safe to challenge the status quo. When I did so, I was most definitely marginalized. To maintain my ability to empathize with the clients and at the same time fend off the wrong-headed approach that was almost a 100% agreement among the staff was a constant stress that eventually drove me out of the field entirely.

Report comment

Steve,