I sat and stared at the television screen—wall to the left of me, parents to the right.

My vision was tunneled, bordered all around by a fine and delicate fuzz.

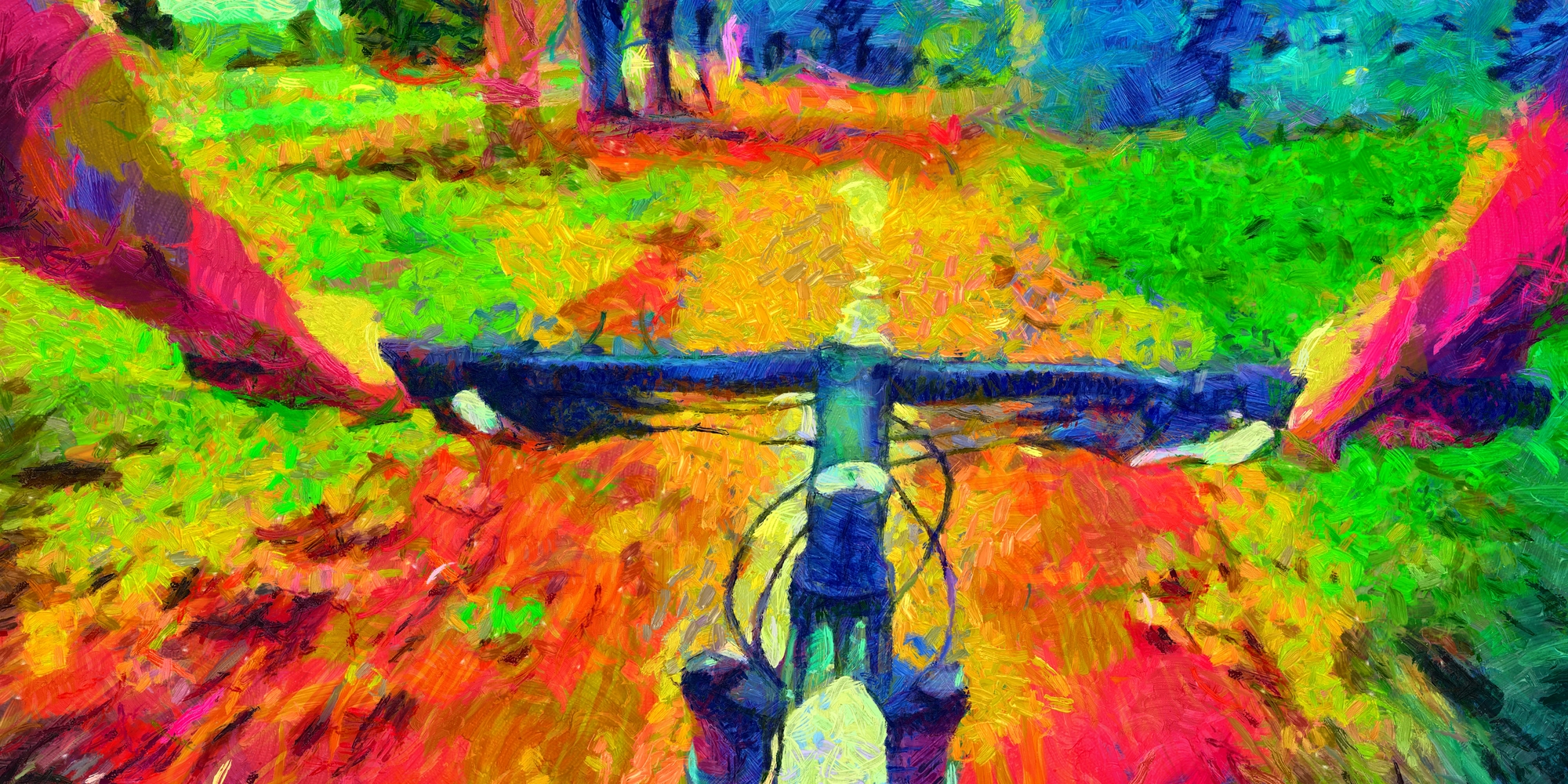

Adorned with birds and trees that morphed and faintly breathed, the wallpaper melted downwards in a waxy sigh. Geometric patterns ghosted on the rug beneath—spiderwebs with rainbow trims—while the TV perimeter burst in haloes: brilliant auras that licked the surround in tongues.

I turned to look at my dad, who, like usual, sat with a hot dinner plate on his knee with legs crossed. He was probably nursing a whisky. When I turned back to the TV, his silhouette lingered on, as if etched out in thin air—its tone metallic, golden—and almost waiting to be pasted in with scissors and glue.

It’d been a month or so since I took that acid, but things had been strange ever since. It was 1-P LSD, to be precise: a ‘research chemical’ that most likely hydrolyses into old-fashioned LSD in the body.

It didn’t take long for me to notice things had changed. The first sign was on the Monday after the Friday, I think, when I’d had the trip. I was only seventeen then—still in high school—and utterly unprepared. It was my fourth session: two hundred micrograms on white-coloured blotter. It took place just a week after I’d taken the same dose with similar difficulty. Even The Beatles sounded scary.

And being caught (and understandably, and severely, told off) by my parents in the long comedown didn’t exactly help with ‘re-entry’.

A recognition

That Monday began with the normal morning ritual: with my friends, chatting, waiting for class to call first-thing. I guess the conversation at hand was how my trip the previous Friday had gone. ‘My parents caught me’, probably being my primary response. ‘I had to chuck all my tabs away.’

I studied the carpet and saw something awry. A strange starlike formation: a faint glimmer of sparkles and shining aberrations. Almost like the static of an undialed analogue TV. It wasn’t there before. I was sure of it.

As the week went on, the visions only became more apparent. Lying in bed at night, I saw the cupboards and wardrobe in front caked in bright colours, oscillating on their hinges. The whole vision-scape would melt and warp.

I went to a Catholic school, which meant a fortnightly mass in a big chapel. That was getting oddly psychedelic, too. I’d space out, lost in the skeletal geometry that wafted on people’s blazers. The red-brick tones of the building would stretch downwards—as did Jesus, emblazoned on the crucifix.

I remember telling a friend in biology class that the blinds were behaving like wet putty. I think that put him off trying LSD, a drug in which he’d expressed interest after my initial evangelical enthusiasm. I distinctly remember wandering the school car park during recess, struck by a surge of tinnitus and mental fog.

What the fuck is happening to me?

I can’t quite recall what I plugged into Google—or when, in the scheme of my experience—but it all clicked when I saw that Wikipedia page.

Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD).

“…a chronic and non-psychotic disorder in which a person experiences apparent lasting or persistent visual hallucinations or perceptual distortions after a previous hallucinogenic drug experience”.

Huh. That makes sense. That GIF looks just like what I saw on that carpet.

The meat-and-potatoes of HPPD

At a most basic level, HPPD occurs when people report changes to their perception after taking psychedelic drugs. The current literature describes two types.

The first—helpfully-named Type 1—is the ‘flashback’ phenomenon, when people feel like they’re flung in the crazed scapes of a psychedelic experience in episodic, often unpredictable, bursts. Type 2 describes a more lingering phenomenon, in which one’s everyday perception is noticeably altered.

Diagnostic HPPD, as defined in the DSM-5, occurs when these changes create distress: something common, but not guaranteed. Many have learned to live with their HPPD, or reframe its changes as sources of enjoyment and reflection.

These changes were recognised as early as 1954, and later defined in broader terms as ‘flashbacks’ by authors in the late-1960s. HPPD, however, was first codified by Dr. Henry Abraham of Tufts in 1983, who had consulted with hundreds of HPPD-reporting patients since the early 1970s.

Reports of HPPD encompass a staggering and ill-defined breadth of experience, but the mass of visual effects is broadly stable among its subjects. The ‘sparkles’ I noticed on the floor—but also the sky and surfaces—are usually called ‘visual snow’. ‘After-images’, or when the bleached silhouette of an object appears elsewhere when you look away, are very common—as are ‘trails’, or the classic psychedelic symptom of faint replications following an object in motion.

Tunnel vision, bordered by distinct kaleidoscopic fuzzing. Splashing colours. Geometric patterns. Melting walls and moving objects. A curious head pressure, which feels to me like a homunculus pressing a hand against my face. Acute light sensitivity, in which people’s visual field can bleach at the slightest sense of a light source. Some people have to wear special filtering sunglasses to navigate. Other somatic changes are described: ‘electrical’ feelings throughout the body, acute neck pain, bodily remembrances of the psychedelic state. These changes can affect people’s ability to read and drive, particularly at night.

People assign to HPPD a range of cognitive-emotional phenomena, too: disordered thinking, insomnia, enhanced hypnagogia, intensely lucid dreams, dyslexia, ‘head fog’, even onsets of stammering, as well as debilitating anxiety and depression. There seems to be a special correlation between HPPD and Depersonalisation/Derealisation Disorder (DP/DR), which occurs when people feel a radical disconnection from their bodies, the environment, and the contents of immediate experience. Since DP/DR so often follows traumatic events—and, as listed in the DSM-5, is itself implicated in visual changes—it’s possible that some people’s HPPD is an expression of unprocessed trauma.

It’s noteworthy that HPPD is described in pitch-perfect terms by Dr. Stanislav Grof, the famed LSD researcher, in his work LSD Psychotherapy from 1978. Based on his work with an estimated 5,000 patients from the 1950s to the 1960s, Grof wrote that “[l]ong after the pharmacological effect of the drug has subsided, the patient may still report anomalies in color-perception, blurred vision, after-images, spontaneous imagery, alterations in body image, intensification of hearing, ringing in the ears, or various strange physical feelings.

“Sometimes, various combinations of the above emotional, psychosomatic, idcational and perceptual changes constitute completely new clinical syndromes which the subject has never experienced before The occurrence of new forms of psychopathology can be understood as a result of activation and exteriorization of the content of previously latent unconscious matrices. These symptoms usually disappear instantly when the underlying material is fully experienced and integrated.”

While similar changes are reported after using many different kinds of drugs—as we’ll see later—the phenomenon of HPPD points to a special correlation they share with psychedelic drugs. LSD, magic mushrooms, ayahuasca, 2-CB, ibogaine, salvia, etc., and also related (but not classically psychedelic) drugs like MDMA, cannabis, dextromethorphan (DXM), datura, ketamine, and diphenhydramine (DPH) are implicated.

LSD stands by far as the leading cause of HPPD in case reports and forums—possibly due to its extended duration and long, difficult comedown, or perhaps as an incidental effect of its being the most used psychedelic drug.

Cannabis isn’t to be underestimated, either: some evidence suggests it’s a common cause, and a tentative consensus indicates the drug can be a powerful catalyst for triggering faint or dormant changes. Others self-report—perhaps in a way unaligned with the real diagnostic criteria—that their HPPD only appears while stoned (and perhaps lingers in the succeeding period). Indeed, many people claim that their hitherto-mellow cannabis highs became ‘like trips’ after they began taking hallucinogens, which may be related to HPPD in a roundabout way.

HPPD’s frequency is uncertain. From off-the-record conversations with friends in the psychedelic community, it seems that fleeting, periodic changes at least are par for the course. A survey held via the drug information site Erowid in 2011 found that around a quarter of 2,700 psychedelic users surveyed lived with some permanent visual change, and 4.2% to a degree that warranted clinical help: suggestive of diagnostic HPPD.

Likewise, a 2010 survey of 626 subjects via Imperial College London found that 34% experienced moderate perceptual changes after using psychedelics, and 6% more extreme changes. Of the 40% total, 73% reported that the changes did not bother them at all, 24% reported that they would rather not have them but could live with them, and 3% reported distress.

The 2011 survey in particular has come under some scrutiny, but there’s still every reason to consider HPPD a more than marginal issue. Membership of HPPD support forums on Reddit, Facebook and HPPDOnline.com number in the dozens of thousands; search up ‘HPPD’ on a platform like TikTok, and you’ll see videos tallying millions of views by influencers describing their experiences, with comment sections abundant in those reporting the same. The popular YouTuber and journalist Andrew Callaghan, for instance, ‘came out the closet’ this year.

It seems that people don’t have to take a lot of psychedelics to develop HPPD. People report them after positive, single experiences with tested drugs—some as little as a microdose—while others do so after dozens. Abraham suggested that HPPD may fall into four tranches: those who never develop it, those after one or two, five-to-ten, and then many more, as a possible function of epigenetics.

These effects can last anywhere from a few days to several years—some people live with them for decades. Up to 50% of HPPD patients’ symptoms may remit after five years, although this needs corroboration through further research.

Writing six years after I developed HPPD, it may surprise you that my visual changes have still not gone away. They wax and wane—correlates of background worry and stress, fatigue, caffeination, and simply spending time alone—and aren’t anywhere near as florid as their first onset, but they remained tangible, occasionally entertaining, and often isolating, for at least four of those six years. These lingering, invested changes in my perception have been matched by occasional bona fide flashbacks, too. In fact, I had one just the other week: a strange psychedelic surge while immersed in a session at an acting class. Not distressing, just weird.

The psychedelic renaissance

Why care about HPPD now?

A simple reason. Many readers will be aware of the burgeoning ‘psychedelic renaissance’ in psychiatry and mental health treatment, around which the coverage is now so positive that it’s causing researchers real concern.

Distressing HPPD has not yet been observed in clinical trials, whose samples are small and heavily screened. As therapies scale to mass populations and criteria are relaxed, however, it seems plausible that some will develop the condition in frightening ways—not least since HPPD is comparatively under-emphasised and little known.

“Increasing numbers of persons [have begun] to arrive at psychiatric clinics and medical emergency rooms throughout the country with symptoms following LSD ingestion”, one author wrote. “This [has] occurred at about the same time that the mass media [has] publicised LSD—unfortunately often in a seductive, alluring way—as a panacea for man’s problems.

“Most of the major magazines, newspapers and television networks have featured one or another aspect of LSD, including, for example, its alleged use in helping architects build better buildings and enhancing creativity in art and music. It has been publicised as an answer to a variety of sexual problems and problems of living in general, as well as a revolutionizer in the treatment of mental illness.”

This was written fifty-four years ago. We’re treading the same ground. And for all its problems and later propaganda capture, as we’ll see later, the ‘flashback’ literature of the time—in its attempt to taxonomise different kinds of re-occurring phenomena, beyond a blanket label—was arguably more developed than the HPPD papers of today.

The role of hype makes sense with my story, too. Six years ago, when I developed HPPD, the ‘psychedelic renaissance’ was still in its infancy. The PR around ‘promising’ clinical trials was small and limited: grist for the mill in enclosed psychedelic circles. Yet I was still encouraged to ‘experiment’ by media of this kind. Two studies in particular tipped me: one by researchers at Johns Hopkins, which indicated that single psilocybin sessions could tally among the five most meaningful experiences of one’s life. That meant my life—and it was in a study, I assured a concerned friend.

Second, a still-circulating 2010 study authored by Professor David Nutt, which suggested that LSD and magic mushrooms make for very little harm, either to users or society at large. As a naive 17-year-old, I wasn’t conscientious of the paper’s deeper flaws: that it doesn’t weight for the absolute volume of use, that defining, demarcating and quantifying the risks of drugs (especially the subtler ones) is a fraught task, and that Nutt is an anti-prohibition campaigner with a clear agenda.

What’s more, the media environment in which these reports are shared seems to have deteriorated in the six years since. In particular, we’ve seen the acceleration of the ‘attention economy’, where quick headlines and Facebook abstracts trump in-depth analysis. The focus-withering, disembodying effects of smartphones seem to make ‘integrating’ psychedelic experiences more challenging, which may lend itself to HPPD.

With all this in mind, I fear that many well-intentioned, curious people will wake up with an effect they never knew possible in times to come. Beyond the appearance of HPPD in clinical settings, I worry if an ‘outside-the-lab’ surge will frighten regulators, much as it did in the 1960s.

‘Outside-the-lab’

While researchers may despair at the unintended effects of their good work, positive coverage precisely encourages people to trip themselves off their own back, including to self-treat mental health issues described by headlines.

A scan of the last few months’ worth of coverage is instructive. The Financial Times asked if “mind-bending mushrooms [could] hold the key to happiness.” Will Smith and Coldplay’s Chris Martin—adding to a lineup that numbers Joe Rogan, Mike Tyson, A$AP Rocky, Reggie Watts, and others in its ranks—‘came out’ as beneficiaries of psychedelics, and Stella McCartney a “fan of fungi.”

Men’s Health wondered whether ayahuasca, an extremely potent hallucinogenic beverage, “could cure veteran’s PTSD”, supplementing a previous headline that it “could cure all of life’s ills.” Newsweek queried if “magic mushrooms may be the biggest advance in treating depression since Prozac”. Good Housekeeping called psilocybin the “magic cure”.

There’s every reason why non-clinical environments would make HPPD more likely. Otherwise-screened-out mental health concerns—the very factors that may motivate people to trip—could be correlated and co-morbid with visual changes; evidence also suggests that one’s risk of HPPD is raised with challenging psychedelic experiences (AKA ‘bad trips’), which are more probable in unobserved environments where events can spiral. HPPD may be more likely with ‘research chemicals’ sold as LSD or MDMA, including 25I-NBOMe and synthetic cathinones (‘bath salts’).

Use by US college students is now at its highest in forty years. Popular access is growing likelier by the year. Several cities have decriminalised psychedelics to some extent or another: most recently Seattle and Detroit, possibly the state of California next year. Easy access is already a de facto reality, too, given the rapidity and scale of darknet markets in mediating the traffic of drugs.

At the same time, we’ve seen the founding of a ‘hotline’ for ‘bad trips’, and a slow-and-small emergence of ‘integration groups’ that help people to make sense of their experiences. We see courses to train a new generation of psychedelic therapists. With the current pace of uptake, however, I’m doubtful that our infrastructure is anywhere near sufficient to absorb all the risk.

Early reports indicate that counselors, psychiatrists and the ‘caring professions’ across the board are unprepared and unconversant in psychedelic experience. ‘Integration’ therapists are expensive and few in number; ‘integration’ itself is fast becoming a buzzword, and there’s little certainty about how best to do it beyond bread-and-butter changes.

And in the gap left by inaction and incomplete information, actors with their own agendas—self-styled shamans, unregulated counselors, Instagram gurus—will likely pick up the pieces, and often in ways that re-traumatise and exacerbate people’s problems. All this suggests to me that HPPD may well linger in the cracks—putting aside the fact that even ‘official’ psychedelic therapy guides can be predatory and exploitative.

It’s curious that a survey of Native American peyote consumers found no evidence of lingering visual change. It’s possible that, with its poverty of an embedded and legitimised psychedelic mainstream, our culture lacks the shared space in which these experiences can be ‘processed’ in full, which may produce HPPD reports.

It’s instructive that many of the panicked posts on HPPD forums are by terrified teenagers, much in the same place I was in 2015. It’s in adolescents’ deepest nature to experiment. We should do everything we can to ensure their ill-considered trips don’t go wrong—including being far more cautious about what psychedelics are capable of.

When perceptual changes go wrong

I hadn’t heard of HPPD myself. I didn’t know such a thing was even possible before it came on. From speaking to a number of HPPD patients over the past two years, it seems that they didn’t, either. They’d believed, like me, that psychedelic drugs were functionally harmless: non-toxic, non-addictive, healing—if only those ‘drug war myths’ would go away, more people could join in and free their minds like us.

‘Flashbacks’ were one of those myths—often tied to outright lies that LSD can linger in the spinal column or one’s fat cells, and be released in a supercharge at any moment. And even if they were real—which I’d doubted—they were phenomena we could countenance as merely “rare”, and probably not worth paying much attention to.

For me, that shield of “rarity” is a red-herring. Not everyone finds their visual changes distressing. Yet for some portion of their subjects—for a range of possible reasons—HPPD is implicated in cases of extreme, genuinely degrading psychological and emotional suffering. It doesn’t matter if it’s a minority. We don’t want people to get hurt anymore.

Stan is in his mid-40s. He’s experienced HPPD for the last thirty years. It began the day after an LSD trip; the perceptual changes have never lessened in intensity. “When I wake up, the first thing I see is billions of fucking dots everywhere”, he tells me.

He sees whirlwinds and flashing spears of light. Tiles and surfaces breathe and morph, coated by implosions and explosions and geometric patterns. The visual effects are so apparent in dark environments that Stan has to sleep with a light on. He is unable to work and lives on disability welfare.

Despite years of introspective work to process and make sense of his HPPD, Stan is still near a breaking point and struggles with intrusive thoughts of suicide. He finds it difficult to socialise and form relationships, and lives life largely disconnected from friends and family. The visuals are simply too intrusive.

“It’s fucking torture”, he tells me. “No human being can endure this.”

Stan isn’t alone in his extreme experience of HPPD, either.

A small, albeit problematic, survey of HPPD patients found that over 90% experienced anxiety and depression, and 69% suicidal ideation. Following through on suicidal thoughts is not unheard of. It can come out of nowhere. I was told of a British HPPD patient whose condition had stabilised. By the following Christmas, however, his family let forum members know that he’d committed suicide with a shotgun.

Alcohol and prescription drug dependence are sadly endemic for those who struggle with their symptoms. As well as dulling their anxiety and panic, it seems that alcohol and benzodiazepines lessen the intensity of people’s visuals—which makes sense given GABA’s neurochemical role in re-filtering visual noise. Abraham likewise suggested that as many as one-third of HPPD patients may experience alcoholism; I’ve heard second-hand reports of several HPPD patients “drinking themselves to death”.

Mark developed HPPD after a trip on LSD in 2005. Barring the visual changes, the worst effect was a “weird anxiety that seemed to envelop me like a blanket”, he says—something that came about in precise alignment with the other changes, and which he’d never experienced before.

“What if your thoughts weren’t necessarily all that negative—and yet you were always on the verge of a panic attack for no apparent reason?”

After some time, Mark’s condition seemed to lessen—but the anxiety “returned with a vengeance” after a binge drinking session, and the visuals following his re-prescription with SSRIs. “Neurologists don’t have a clue, so how would I?” he asks.

The unknowns of HPPD

Tragically, while advances have been made, our understanding of HPPD remains about as scant as when I saw that first visual. Being an ‘orphan condition’—without the big name and public health purchase of conditions like schizophrenia and depression—HPPD lies in a nowhere-land where funding for studies is hard to come by. The evidence base is largely confined to handfuls of case reports, involving as few as two people.

We know little of how HPPD originates, what risk factors may be at play, or what treatments are truly effective. Psychotropic drugs like Lamotrigine, Keppra, Klonopin—primarily anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines—have anecdotally helped many people transition beyond distress and lessen their visuals, but they don’t work for everyone. Being blunt, untargeted tools, they can bring nasty side effects, not least when withdrawal from benzodiazepines is, curiously, correlated with very similar visual changes.

Many HPPD patients who seek clinical help face stonewalls and low awareness from doctors. Abraham, the originator of the condition, estimated that the typical HPPD patient goes to as many as five different types of clinicians before finding one who understands.

Speaking with David Kozin, the former moderator of the popular HPPDOnline forum, it was striking to hear that he routinely coached patients into avoiding certain keywords in session with psychiatrists. If they describe their visual changes as ‘hallucinations’, not least when triggered by a drug like LSD, HPPD patients may be liable for misdiagnosis with drug-induced psychosis or schizophrenia, whose treatment with antipsychotic drugs can greatly-exacerbate one’s symptoms (while, oddly, helping others). SSRIs can likewise synergise in all the wrong ways, while, again, remedying the symptoms of some patients.

As if the picture wasn’t already weird enough, psychedelic drugs seem to help some people overcome their HPPD: including psilocybin, ketamine, LSD, and ayahuasca. Careful LSD dosing was how Stanislav Grof claimed to resolve his HPPD patients—he suggested a re-entry to the psychedelic state allowed for the integration of ‘unconscious material’, which was expressing itself in visual change. I know of a friend whose small lingering visuals, induced by 1-P LSD, disappeared after a subsequent trip with LSD proper. Yet others report permanent deteriorations if they so much as smoke cannabis again. The whole field is soaked in unknowns.

Is ‘HPPD’ failing patients?

While a useful pointer—and a label for very real experiences—HPPD is nonetheless ripe for conceptual revision. The DSM-5 diagnosis of HPPD requires that the person be re-experiencing the prior effects of hallucinogens—which collides with the cold fact that drug classes of many kinds are implicated in similar (if not identical) visual changes: SSRI antidepressants, antibiotics, antipsychotics, and nootropics. Even then, the view of HPPD visuals as ‘imports’ of the psychedelic state seems, at best, incomprehensive: in my experience, ‘visual snow’ in particular never made an appearance in any trips, and neither did tunnel vision.

As I’ve said, though, with visuals of this kind it seems that psychedelic drugs are especially prone to creating them. It’s as if they supply a higher ‘risk factor’ for an always-possible condition—similar to how smoking cigarettes raises the odds of lung cancer, which people can still develop without ever having smoked. It’s conceivable that psychedelic drugs have a ‘value add’ effect, in terms of HPPD’s visual and cognitive changes above other chemical causes. I struggle to believe it’s a coincidence that powerful, vision-altering drugs alter one’s vision ‘just like’ everything else in the pharmacopeia—or that, if the drug’s effects linger, their psychological energy simply ‘dissipates’ and returns to baseline.

I’m curious, too, whether psychedelic drugs may sometimes be better situated as a subtype of ‘intense experience’ triggering lingering phenomena. I’ve heard second-hand anecdotes of people developing HPPD-style changes after meditation retreats, for example, which can trigger mental health episodes of many kinds; I see reports of similar changes during meditation sessions, and following descriptions of spiritual events like ‘Kundalini awakenings’.

The picture is further confused by ‘refractory periods’ that delay the HPPD onset. Where many—like me, Stan, and countless others—see their first visuals in the first days after a trip (if not the next day), others take weeks or months. What this means, I expect, will vary from subject-to-subject, and further lends emphasis to the crucial role of context in embedding a psychedelic trigger. One case report describes an onset of twenty years, which seems to stretch credulity. Perhaps it speaks to the easy blame that hallucinogenic ‘drugs of abuse’ can take in strange visuals. Yet there may be dormancy effects that we still haven’t described. We just don’t know.

Crucially, HPPD shares enormous diagnostic and symptomological overlap with another condition, Visual Snow Syndrome (VSS), whose patients have likewise struggled to achieve recognition from mainstream medicine. As well as the visual changes—after-images, haloes, and, of course, visual snow—the overlap can extend to other problems like tinnitus and dissociation.

All these experiences are not necessarily abnormal, either: in conversation with my sister and friends, for instance, I heard that they also saw ‘visual snow’, and lots of people have ‘floaters’. Some people report VSS from birth. To some extent, dissociation is part of human functioning, though DP/DR embodies a more extreme and distressing case. These visual experiences are even seen in those with generalised anxiety disorders, who may or may not be eligible for diagnosis with VSS. Tentative evidence indicates that people who develop HPPD may already have had these visual experiences, with the psychedelic acting as a catalyst to raise their noticeability.

With more time and dedicated research, it’s entirely-possible that we’ll collapse HPPD into a psychedelic-induced subtype of Visual Snow Syndrome. As described above, however, it’s also possible that HPPD remains a distinct phenomenon, at least for some portion of its existing cases. HPPD subjects may report more florid, psychedelic visuals, perhaps as stored memory imports of their experiences. It’s instructive, too, that migraine auras—something implicated again in similar visual changes—have a distinct neurophysiological pathway from VSS. Some evidence indicates that HPPD patients report fewer migraines than those with VSS.

These concerns aren’t academic. If HPPD’s conceptual structure is malformed, that fails patients. It misinforms clinicians. And, as I’ll argue later in the piece, the frequent impulse to pathologise perceptual change as HPPD poses its own unique risk—primarily by raising the concomitant distress that makes us care about HPPD altogether.

The HPPD isolation

In the year after I first developed HPPD, my hope of recovery would only become more remote with time. I’d turn and look at the wall and hope it wouldn’t melt, and soon be disappointed. I couldn’t tell my teachers and my family, of course—only a few friends, who, I suspect, didn’t know what to say.

While the changes became my normal, I grappled still with a gnawing sense of isolation—not assisted by a destructive belief common to HPPD patients that I’d ‘fried my brain’ and become an ‘acid casualty’.

Indeed, through introspection on my own experience, it’s become clear that a huge part of the ‘HPPD problem’ is how easily it vessels anti-drug stigma. I couldn’t tell my teachers about what I was going through, even the ones I really liked, because I’d done drugs. The room for empathy is always limited when ‘you did this to yourself’, but HPPD is different. A condition like Visual Snow Syndrome, meanwhile—whose effects, as outlined earlier, can be nigh-on identical—attracts a far more intuitive sympathy.

Even if I’d been penitent and resolved never to take LSD again, my admission to teachers would have spelled instant expulsion. It’s amusing, and tragic, to reflect that acquaintances at school were kicked out without rejoinder for possessing cannabis—a shock that, if anything, could make drug (ab)use more likely for them—while bullies and purveyors of racism against ethnic minority pupils got slaps on the wrist. And for all the school system’s ‘hard line’ on drugs, it’s also amusing that I never received an atom of objective information about the risks of drug-taking. The only mention I remember was an assembly warning about ‘hippie crack’, or nitrous oxide, and why it would necessarily destroy your life.

If things were in working order, we’d recognise that schoolkids do, and will almost certainly go on to do, drugs, including psychedelic ones. Perhaps a fair presentation about HPPD would have put me off tripping at such a young age, if only for a year or two while I matured and my brain developed. And more than dress it up in the cultural mythology of spinal fluid flashbacks, telling the honest truth that HPPD can, but does not necessarily, create distress, would have lent teachers’ warnings a far more compelling credence.

As I’ve mentioned, many sufferers of HPPD are plain teenagers. They’re the ones for whom our culture’s warped relationship with drugs is at its most potent.

The psychedelic conversation

Yet the school system is only a node in a broader conversational problem. From a young age, we’re taught that drugs are always bad. In fact, ‘bad’ is almost part of drugs’ entire conventional definition. What people often find when they actually take drugs, especially psychedelic drugs, though, is that they’re enjoyable and useful. They can even trigger spiritual experiences, which we tend to disown and pathologise in a culture disenchanted and over-secularised.

But once people come down, they face a culture in which their deepest experiences are literally criminal. They’re on the back foot, defensive and armed with arguments, from the get-go.

In the psychedelic community in particular, the inevitable result of that dynamic is toxic positivity. While rapidly maturing and far more considered than in the past, it makes for a culture where sharing difficulty can feel harder than it should. And with positive headlines all around, we don’t want to spoil the fun or derail the train. The likely presence of a ‘survivorship bias’, where those active and vocal are those who haven’t been disabled by their psychedelic use, further alters the landscape.

This has implications for HPPD. It’s distressing to hear that many in the HPPD community don’t feel listened to, if not actively marginalised, in the psychedelic conversation. Where HPPD is discussed, some energy is still parked in the question of whether it exists: not a useless question, but the wrong one to ask at a time when people’s experiences are real, and they need help. And while visual oddities after psychedelics may be relatively commonplace—at least in limited form—it seems that people hush up and don’t discuss them, perhaps for fear of indulging anti-drug ‘flashback’ narratives: understandable, but it needs to change.

Indeed, all the toxic positivity only plays in the isolation people can experience with HPPD. Part of the reason why I felt so challenged in opening up to my family—it took five years, all in all—is that I didn’t want to indulge an anti-drug narrative that gaslit my own spiritual experiences. While my schoolday trips left me with an often challenging HPPD, they were also home to the most memorable and life-changing hours of my life.

This points at another source of suffering some experience: that, if you’re being ‘sensible’, you can ‘never trip again’. While those naive to psychedelics may struggle to empathise, this pain amounts to a kind of mourning. Having glimpsed Eden—to borrow a phrase from Richard Alpert/Ram Dass—the fences are up and you’re now barred from entry.

A year or so after I developed HPPD, I took a risk and continued experimenting. I was blessed, and tallied some truly-profound trips with LSD, psilocybin, and later 2-CB. Note, my HPPD did not deteriorate. I guess I was lucky.

In fact, in their own strange and tricky way, my perceptual changes perhaps came in handy. Earlier this year, a powerful, semi-visionary experience with cannabis—a drug, as mentioned earlier, often made more psychedelic with the onset of HPPD, and therefore maybe more introspective—inspired me the following day to ‘come out’ to my family about my HPPD experience: something that balmed the alienation that had accounted for the mass of my distress.

All in all, drugs are complicated. You can’t have subtle, value-neutral conversations about drugs in our culture, though. It’s always black-and-white.

The problem of perception

But HPPD isn’t just a matter of anti-drug stigma. It also cuts to something deeper.

What one sees is so basic a category of experience that any serious gap can undercut one’s ability to empathise and connect. We can think differently and run on different beliefs, but there’s something unique about the public sphere of our perception that’s affecting. As Dr. Tehseen Noorani, a London-based psychedelic social scientist, emphasised to me, our shared space for perception arguably provides the deepest codes of how we commune—our capacity to share in culture, politics, and society. Being mediated through eyes everyone can see, any major differences in vision seem to tear away at a delicate fabric.

Many times, I remember being there in a room with others—laughing, chatting, watching TV—but the basic difference of vision became a self-binding trap, as if I was locked in a private wonderland of my own perception, forever cut off from the world ‘before’.

Once I went to university six months after their onset, the changes only seemed to ramp up. The background stress and worry that followed me for much of that year filtered into my visuals. For a second or two at a time—and for reasons I struggle to grasp—my vision would blacken and coat with coloured stars: events I self-stigmatised as ‘schizophrenic flashes’ to the one friend I could tell. That terror around schizophrenia isn’t unheard-of for HPPD patients—not least when psychedelics have long-been associated with the condition in the fear-borne popular consciousness.

Staring at professors in front in enclosed grand halls, my lectures and seminars would sometimes spiral to real lysergic terrains. It wasn’t necessarily unpleasant. I’d enjoyed my LSD trips, for the most part. Since I didn’t tell anyone what I was going through—again, for fear of seeming ‘weird’, or indulging that I’d ‘fried my brain’—it was the isolating effect that got to me more.

I remember attending a drinks event to welcome new admissions to my major. I made a friend, who, like me, was a fan of 1960s psychedelic rock—the same cultural mass that had encouraged me to trip, alongside those studies I described earlier. It was wonderful to meet someone I had something in common with. Then I glanced across the room and saw the visuals appear again. A strange ball-and-chain trimmed in rainbows.

The online world of HPPD

For much of that freshman year at university, I stayed sober and focused on meditation. I did not touch psychedelics, aside from a microdose experiment that seemed to intensify my HPPD in the short-term.

Instead, I started spending more and more time on the HPPD support community on Reddit. Like many, it was reassuring at last to ‘find the others’, and discuss tips, best practices, recovery stories, and vent distress. Personal details are shared, too. I know of at least one marriage struck on the forums.

I’m often stunned by the degree of expertise and independent research HPPD patients share. Between the cracks of mainstream medicine and the emerging psychedelic sector, it’s equal parts assuring and concerning that everyday people with disabling impairments have had to take it upon themselves to work out what’s happened. Scan the forums, and you’ll see lengthy monographs on receptor relationships, psychodynamics, alpha waves, EEGs—any number of issues relevant to HPPD in whose details, I expect, few psychedelic researchers are conversant.

Indeed, the nonprofit I’m now working with, the Perception Restoration Foundation, emerged as a bottom-up solution by the HPPD community. The same applies to another active nonprofit, the Neurosensory Research Foundation.

There’s a downside to this community, though. They can feel like dens of negativity, hypochondria, and infect patients with distress; I’ve seen fears over the effects of the COVID vaccine. Overcoming the emotional costs of HPPD is largely a matter of getting on with your life. That’s something many learn the hard way. Focusing on one’s experience only makes them more noticeable.

As the moderator and longtime HPPD name David Kozin put it to me, HPPDOnline.com in its 2000s heyday was “like running a psychiatric hospital—[except] where no one has any idea of the right treatments, and everyone is by definition a felon.”

“You should leave this [forum] because reading these horrible stories will do absolutely nothing for you”, one user posted on the HPPD subreddit.

“I never even abused psychedelics. I only took them twice. It’s almost a year and it only has gotten worse. This subreddit, instead of giving me hope, has made shit worse. I live with regret everyday. I never expected this. Either way, I’m done with this subreddit”, another wrote.

With nowhere to turn but the forums—not family, not doctors, not the psychedelic community, not the cultural mainstream—people can slip into destructive experiences that render diagnostic HPPD (over and above perceptual changes per se) more likely.

The psychedelic risk

As a neglected risk of psychedelic drug-taking, HPPD is not necessarily unique. The storied ‘shutdown’ in research over decades in psychedelic medicine didn’t just conceal its purported benefits—but also its real and possible costs.

Philosopher and commentator Jules Evans, for instance, has pointed out that no research exists at all on the best ways to process ‘challenging experiences’ (‘bad trips’), which, again, are implicated in HPPD risk.

While useful, I suspect that conventional ‘integration’ advice around journaling, exercise, ‘remaining grounded’, and ‘drinking plenty of water’, is often not enough to absorb the psychological shocks induced by psychedelic experience. Like the founder of ‘Somatic Experiencing’ Peter Levine, I also suspect that psychedelic experience is so ipso facto overwhelming that its psychic effects deserve very special care for everyone—not just those who had ‘bad trips’—to avoid lingering trauma.

As emphasised to me by the cognitive scientist and consultant Marta Kaczmarczyk, even our best and most euphoric trips may be subtly traumatising. In a provocative talk at 2019’s Breaking Convention, the UK psychedelic conference, Kaczmarczyk outlined that early neurochemical evidence—which I’d never imagined or encountered till her presentation—suggests that psychedelic drugs could create lasting anxiety and stress through their effects on the 5-HT2A receptor. It made me reflect on my own experiences, which did seem to be bookended in the weeks afterwards by uncomfortable degrees of arousal.

These concerns are flaring. In the recent Phase 2b clinical trial held by COMPASS Pathways with psilocybin, many in the psychedelic community were struck by the correlated prevalence of serious adverse events, including problems of suicide. Another trial into the hallucinogenic brew ayahuasca described how a quarter of its participants were hospitalised afterwards, albeit for reasons not exactly clear.

Post-psychedelic mania is likewise neglected and maybe under-reported, as are depersonalisation and dissociation. The possibility space of psychosis, usually chalked up to ‘family history’, ‘bad set and setting’, or mis-dosage, needs more exploration. As I argued in a lengthy Twitter thread, psychedelic addiction—usually sidelined as impossible—can be very real and subtly corrosive.

As a rule, many of these risks can be framed as problems of ‘integration’: that, with adequate aftercare and sense-making in the days, weeks, and months afterwards, they’ll resolve themselves, and perhaps feed a deeper process of growth. This is very true.

I’ll reaffirm, though, that integration is not only under-explored, but also likely to degrade in times to come—primarily because of the attention economy. The growing shift to digitise psychedelic integration through apps, and the possible and conjoined incentive to cut corners with for-profit clinical firms, should be watched and monitored carefully. At a deeper level, the extreme positivity of psychedelic media—currently cycling with press releases, stock prices, and hype—needs a step-down.

How should psychedelic medicine handle HPPD?

HPPD lies in its own strange space. On the one hand, the sudden onset of perceptual changes after drug-taking is clearly, at some level, a matter for neurophysiology and the visual cortex. As the psychedelic commentator Dr. Erik Davis told me, a risk of this kind can be a square peg in the wooly, psycho-spiritual round hole of ‘integration’—and it seems the psychedelic community has not yet developed a language for expressing it beyond: ‘Yep. This can happen with drugs. Sorry.’

On the other hand, at least in some cases, HPPD is an issue with obvious psychological drives. The content of people’s experiences deserves close review. In-depth therapeutic work with a bona fide, psychedelically-informed practitioner could be useful for many, and I would invite research and case reports on its effectiveness in resolving either the condition’s concomitant distress, or even the presence of visual changes altogether.

The drive to find a pharmacological remedy for HPPD, while welcome and vitally necessary, should be matched by an equal emphasis on lifestyle change and psychological work—not least since pharmacology may not resolve the deeper change of which visual effects could be symptoms.

Consensus among patients suggests that exercise, recovering and stabilising sleep, staying away from enclosed environments, connecting with others, avoiding isolation, and abstaining—at least in the short-term—from psychoactive drugs can help to lessen distress and visual appearance. I’m curious in particular about the input of ‘healthy diet’, which is usually-framed in blanket terms. Specific dietary and immune interventions may be helpful, and have been explored in the case of Visual Snow Syndrome.

All this will be of particular import for those whose HPPD developed after bad trips, and more broadly to those who also live with post-psychedelic dissociation, anxiety, and depression. Here, if people’s anecdotal reports are enough to go on, I anticipate that psychedelic drugs may be a true pharmakon: a ‘poison’ as well as a ‘cure’, which could address the issues leading to HPPD in much the same way as they treat other mental health concerns.

From here, then, the first two priorities are understanding what leads to distress (and resolves it), and what HPPD even is. We need a working model of how it works and intersects with other disorders like Visual Snow Syndrome, and a proper taxonomy to balance its visual, cognitive, and emotional changes: something that at least one early flashback researcher attempted, which has not been replicated since. This is something the Perception Restoration Foundation is working on through questionnaire studies and neuroimaging via Macquarie University in Australia.

It’s also something I’ll work on in an MSc programme that commences in January. As with the breadth of people’s reports, I expect that ‘HPPD’ will encompass an even broader range of subtypes.

Visual change as an expression of lingering psychedelic-induced trauma. Basic neurophysiological action, as with those who only took a microdose (and the population who took non-psychedelic drugs). A drug-induced spike in baseline anxiety, which may be independently associated with visual changes, and make people more likely to fixate on previously normal and unnoticed features of perception. This anxiety may drive the co-morbid experience of dissociation, too.

I likewise wonder if different types of psychedelic drugs affect people’s experiences—whether DMT-induced HPPD has marked phenomenological distinctions from that caused by LSD, for instance.

It’s time to de-pathologise

In countering distress, though—the real issue with HPPD—the psychedelic sector should tread lightly around treating visual change as a necessary pathology. You may remember earlier that these kinds of visuals can affect ‘normal’ people, or even start from birth. From the name outwards, these changes are viewed as ‘symptoms’ of a ‘disorder’. But what of those who don’t find them distressing? How should we describe them? What of the ‘HPPD patients’ who don’t have the distress that defines HPPD?

Indeed, if you scan online communities beyond HPPD forums—on Reddit, the likes of Psychonaut, LSD, Shrooms, Rational Psychonaut, and beyond—you’ll find that many people, including those with very significant visual changes, do not find them problematic. Visual changes to some degree or another really aren’t uncommon—recall the 2011 finding that as many as a quarter of psychonauts experience a permanent visual change. For this reason, I advise that researchers into the disorder look beyond HPPD forums in gathering qualitative data and study recruits.

For example, lingering visuals can filter in the background and become normal, as they did for me. For those seeking to resolve their changes, the condition can motivate lifestyle changes that wouldn’t have happened otherwise—leading some to be grateful they ever ‘got HPPD’. Still others actively enjoy their perceptual changes—and they shouldn’t be judged for it, either.

“I love my HPPD honestly”, one user says. “… I can hallucinate whatever I want with eyes closed, which has done wonders for my creativity. When I’m bored I often zone out and play with my HPPD. I still drive/read/function the exact same.”

“The view when hiking and looking at the mountain or the star without psychedelics is amazing”, another says. “My CEV and visualisation are a lot more complex and it makes meditation magical. I can look at art, or even better, abstract or absurd art, for hours and it’s better than a movie: the pattern and distortion make me go in a string of fantasy. Ooh, and the clouds: I’ve watched them everyday for at least 30 minutes since the start of the condition. They are so incredible, so free”.

A more spiritual re-framing isn’t uncommon. Some interpret their visual changes as a glimpse into ‘auras’ and other mystic phenomena, while others view them as a lens to the fluid, effervescent character of ‘fixed’ matter. As described earlier, meditators may experience these changes, too. And given psychedelics’ lineage in shamanism, I’d invite research and further anthropological study in how—if at all—these cultures understand HPPD-style events. At least one forum member described a shaman’s take on HPPD as an issue of ‘trapped energy’. And there is the Xhosa tribe in Africa, whose ceremonial use of the Silene undulata ‘dream plant’ is said to make some members “never leave” the experience.

The idea of “loving” a disorder characterized by necessary distress is an obvious contradiction in terms. A new model is needed.

For my money, I’d suggest starting with a broad umbrella—something as simple as ‘post-drug perceptual changes’, or PDPCs, not least since it allows for other kinds of drug-induction than psychedelics. If research shows that psychedelics account for their own unique blend of perceptual change, ‘post-psychedelic perceptual changes’ (PPPCs, or ‘triple-P Cs’) may be an effective genus to describe. (Note, we should hold the fixation on ‘perceptual change’ lightly, because they may [as described] be married to broader changes in cognition and mood.)

And nested within at least the PPPC umbrella is a sub-population, majority or minority (we don’t know), who find their changes distressing: the HPPD patients, who can transition into mere PPPC subjects by recovering from distress.

The ‘model’ is speculative and needs scrutiny. At the very least, I hope its emphasis on the reality of non-distress will make converse distress less likely. Framing visual changes as a problem from the outset only raises fixation, which in turn elevates their noticeability and intrusion. Pathology makes people feel more isolated and self-shaming than they need to be. If I’d been told as a teenager that visual changes aren’t necessarily bad—and been pointed to real examples—I’d probably have been reassured and relaxed.

PPPC, PDPC, HPPD: alongside a space for shamanic and mystic understandings, we should remember that, as with all medico-psychiatric descriptions, labelling in itself can create problems:

“I remember telling my parents when I was a kid that I could ‘see molecules’. It was never an issue, though…”, one visual snow reporter wrote. “Now that I know this isn’t what normal vision looks like, it’s driving me crazy. I can’t stop noticing it and it’s giving me a headache.”

“Brutal man, absolutely brutal”, another described after being diagnosed with Visual Snow Syndrome by a neurologist. “She’s like, ‘Yup, there’s no cure, you’re stuck with it for the rest of your life.’”

More strikingly, the Norwegian psychedelic scientist Teri Krebs pointed me to a case outlined in The Thaw: Reclaiming The Patient in Psychiatry by Paul Genova. It describes a 21-year-old named Dan, who noticed lingering visuals a few weeks after his third LSD trip. Diagnosis with HPPD and subsequent prescription with Klonopin only raised his distress and depression, not least with the drug’s intense side-effects.

Rather, what helped Dan was working with Genova, who leaned into his own capacity for experiencing similar visual phenomena—and experiencing them with Dan.

“[He] reported a great sense of relief and ‘normalisation’ as a result of these few sessions”, Genova wrote. “Before our mutual experiences, the symptoms ‘meant’ that Dan was crazy, different from other people, alone forever in a distorted visual universe.” Now normalised, the “snowballing anxiety” that was really wrecking Dan’s life was under control.

Hold this lightly, though. Think of Stan or Mark from earlier. Some people’s experiences are so powerful that a ‘re-framing’ is at best impossible, and at worst an insult-bearing gaslight. HPPD patients feel neglected, and appreciating the disorder’s distress is crucial to giving them a voice. Even those whose changes are relatively ‘mild’—although objective measures are fraught here—can find them very distressing. It’s the difference that matters, and in whose space the distress can fester.

Neurodiverse psychedelia

More than this, I anticipate that a new conversation around working with visual changes is in order. Rather than view them as a strict ‘side-effect’ of psychedelic use—an outcome to be avoided in clinical settings—there’s no reason why they couldn’t go hand-in-hand with how psychedelics heal.

In particular, many report that psychedelics induce change through strong, emotionally embedded memories of one’s experiences. That there are lingering visuals from a trip could, and do already for many, serve as a special reminder of the lessons and insights they drew: a phenomenological reference-frame for the state of mind they’ve glimpsed is possible. I’ve used this kind of framing for my experience to some success, especially when listening to music—which seems to have been permanently changed for the better in line with my PDPCs (!). This is especially relevant with ‘flashbacks’, whose experience would seem like potent vessels for one’s psychedelic memories.

There’s a bigger question at play, though—one which perhaps relates to the fundamental, distinct character of perception I described earlier:

If we take psychedelics to change our experience, why can’t changes to perception be part of the package, too?

Indeed, as psychiatry awakens more and more to the possible normalcy and adaptiveness of ‘pathological’ phenomena—hearing voices, having visionary spiritual experiences, seeing unusual things—perceptual changes may do well to be situated on a post-psychedelic neurodiversity spectrum, albeit with pathological potential in cases of distress.

The same applies to all the risks I outlined earlier. While mania, addiction, de-personalisation, psychosis, and elevations in anxiety are real, and their disruptive character not to be under-estimated, they may be better-framed in many cases in non-pathological terms—not least given the striking oddity of which psychedelics are capable (especially spiritual oddity), and the power of Looping Effects in creating needless distress. This will take an overhaul of many clinicians’ assumptions. It’s welcome to see moves already in this direction, as with the ‘Psychedelics, Madness and Awakening’ conference held earlier this year, featuring the aforementioned Dr. Tehseen Noorani and Jules Evans, as well as rising voices like Psymposia’s Lily Kay Ross and the Lacanian psychoanalyst Timmy Davis.

The ‘psychedelic renaissance’ in psychiatry may well be ‘promising’. But the harms of psychedelic drugs, including distressing perceptual changes, are real and need to be better known—albeit only in nuanced, responsible terms. By taking ownership of what they can do, in all their colours and stripes, we steal the flag from those with anti-drug agendas, whose messaging only makes those bearing distress suffer more.

How does one reconcile the flashbacks with and/or without drugs? The brain seemingly is creating responses as described by many on this site in response to escalations of verbal, physical and sexual abuse, either knowingly and/or unknowingly with limited ways out of this nightmare. What is required for a better recovery and economy, which affirms our existence as global citizens?

Report comment

At the risk of getting electronically silenced, I’d suggest paying more attention to the work of Hoffer and Osmond, particularly their magnum opus- The Hallucinogens. Although long out of print, you may still find copies in university and college libraries (I’d have to shoot you if you tried to take my copy).

Report comment

Without even reading the article, I found I objected to the title. Why are we calling this “psychedelic medicine?” It is NOT medicine! It is at best “psychedelic therapy,” not a medical intervention at all, but a mental/spiritual one. I find it continuously offensive when things that are potentially helpful to our spiritual needs are coopted by the medical establishment, such that going for a hike becomes “nature therapy,” and doing fun things becomes “occupational therapy” and on and on. “Psychedelic therapy” is distorted enough – PLEASE let’s get away from calling it “medicine!”

Similarly, taking the flashback phenomenon and giving it a “medical” name does nothing to advance our understanding of what is going on. Flashbacks are pretty mysterious, there appears to be no understanding if there is any physical reason for flashbacks, let alone what it might be. People who have flashbacks aren’t “HPPD patients,” they are people who have experienced flashbacks. Why do we feel this need to dehumanize folks by grouping them together, as if experiencing flashbacks is again a failure of the “patient” to respond “properly” to “treatment?” Just as we excuse the failure of antidepressant “treatment” by calling the victim “treatment resistant” instead of just admitting that the drugs have failed to help or have harmed the recipient?

I know that “medical language” tends to get things published, but it’s an insidious slippery slope away from treating people as human beings. I’m not categorically opposed to the idea of using psychedelics to help people find some level of mental/emotional perspective, but the idea that it can become some kind of standardized “medical treatment” is a very damaging absurdity that could very well ruin any chance that the use of psychedelics can develop into something that might actually be helpful to people’s spiritual growth.

Report comment

Hey Steve – as the author of the piece, I agree with many of your thoughts, and I’d urge you to read it if you have the time. The piece aligns with your perspective in some ways. And the headline relates to a specific question covered in the piece, which is how the medico-psychiatric sector – like it or not, the sector acting as the vanguard for the psychedelic renaissance – should handle these phenomena.

Report comment

Thanks, Ed. I have read parts of the article, though it is quite long. I get the idea we’d probably agree on a lot of things. I do think it feasible that psychedelics can be used in a helpful way, but there is little to no chance that the psychiatric profession, or even the profession of psychology, will be able to use it in a helpful manner. Psychiatry in particular specifically denies the validity of the spiritual world, while those who HAVE used psychedelics historically in a helpful fashion are shamans or other spiritual leaders who are helping expand one’s viewpoint of the world, not trying to “cure mental illnesses” that don’t even exist. Without a big change in viewpoint and philosophy, I believe psychedelics will be as dangerous in the hands of psychiatry as any of their “medications.”

Report comment

Well, the Native American Church uses them (well, peyote, at least) in ways beneficial to the members, as did the Province of Saskatchewan, until the US DEA clamped down on it for providing psychedelic experiences to alcoholics to help sober them up, when the Agency “knew” that this was “impossible”.

Report comment

Trade protectionism there. Not surprising.

But yeah, the Native American Church is just the kind of approach I’m talking about. What was it they did in Saskatchewan?

Report comment

In the late 1950’s, H&O began to consider sobering experiences. They’d also gone to a peyote ceremony in Alberta at the invitation of the Blackfeet, who were trying to make their religious peyote ceremonies respectable to white governments. Shortly after this, they created a study using acid to simulate DT’s. While doing this, they discovered that the guys who had the psychedelic experiences instead of the “psychotomimetic” were the most likely to stay sober. From there, they became involved with psychedelic therapy in alcoholics, and devised protocols for proper usage to maximize good results. The government of Saskatchewan was so impressed, it authorized and began to use psychedelic therapy as a first line treatment for alcoholism throughout the province. The Americasn DEA was outraged and forced the province to discontinue psychedelic therapy for their alcoholic patients. (your government hard at work to protect youy from imaginary threats)

Report comment

bcharris, As far as the American DEA involved in this “psychadelic therapy for alcoholic patients” I respectfully disagree with you. Yes, our country has made many terrible decisions that greatly impacted Americans based on “imaginary threats” but this, in my opinion, is not one of them. Of all people, alcoholics should definitely stay farther than a “ten-foot pole” away from psychadelic drugs, among other mind-altering drugs. We, as American citizens, entrust our DEA to protect us from these drugs. Much of the time, they fail. That time they did not. Thank you.

Report comment

rebel, your comment regarding alcoholics avoiding psychedelics is interesting. Are you aware that Bill Wilson, the founder of AA, took LSD and was a proponent of it as a therapeutic agent for helping alcoholics give up drinking?

Report comment

Steve,

“…I believe psychedelics will be as dangerous in the hands of psychiatry as any of their “medications.”..”

I believe the “medications” in the hands of Psychiatry are worse than “Oxycontin” in the hands of Pain Prescribers.

Report comment

booloo, I had heard that Bill Wilson, the founder of AA, took LSD. But, I really would like to see the reference to verify this. From what I know, most recovering alcoholics are advised to stay away from most drugs, especially pain killers and mind altering drugs. It would seem to be as if taking LSD would be exchanging one drug for another (the alcohol.) Perhaps, this is true, but it sounds pretty dangerous to me knowing how these drugs can affect the body and the brain. Thank you.

Report comment

rebel, Don Lattin has written on Wilson in his book Distilled Spirits. You may find this Guardian article of some interest:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/aug/23/lsd-help-alcoholics-theory

I think it important to note that we are biochemical systems, and everything we take into our bodies affects us. The food you consume affects both your body and your brain, and often in ways that are probably more significant than most people realize. Even subtle effects can be significant to how we experience the world.

The term ‘drug’ isn’t really useful when discussing psychoactive substantives, because it is overly broad and isn’t useful when trying to suss out good from bad. While it is certainly true that some drugs pose a serious risk to recovering alcoholics (e.g. opiates), others seem incredibly common at AA meetings (e.g. caffeine and nicotine).

There was quite a bit of work done in the 1950s with LSD and alcoholics, e.g.:

https://maps.org/research-archive/w3pb/2005/2005_Dyck_22866_1.pdf

and there were promising results, but laws changed and this field of study disappeared for decades. That’s changing now, and there is reason to believe we may well see psychedelic therapy for alcoholism as one possible treatment in the coming years. However, there are no magic potions, and simply swilling a cup of ayahuasca or taking 200 mcg of LSD is highly unlikely to turn a life around without additional support and effort.

wishing you well

Report comment

Ed, Steve and others:

The idea may be simpler https://youtu.be/f1x9lgX8GaE though to have clarity of thought for flash forward, backward and even in the Now poses some health risks to the clarity of thinking. The vibrancy of colors on line is different from standing before art in museum or gallery. The values and valuation though that create an economy that is destructive to self and others, even collectively though remains in and of question. And when one is punished for speaking up to address some degree of injustice, then what recourse is there?

Report comment

Lots of Absolutely dreadful Alcoholics use non drug Approaches to sober themselves up permanently, and these non drug approaches can also be found within Buddhism and Stoicism.

Report comment

Booloo, Thank you I will read that article when I get a chance. I think that caffeine/nicotine thing is somewhat true. I remember that my mother worked as a clerk typist for the Drug/Alcohol Resource Center on an Army base when I was in school. And she always came home reaking of cigarette smoke and she did not smoke. But that was before the current “smoking ban” in almost all public buildings including stores, offices, and restaurants in many places, even in “tobacco states.” I do not smoke. But, even after all my years taking the psych drugs, I am horribly “addicted” to caffeine, although I don’t think “addicted” is quite the right word. I am incredibly allergic to alcohol. I can not even eat it in cooked food. A thimble full can nearly do me in and probably endanger my life; but I was never considered an alcoholic. I had an incredible allergic reaction to alcohol one night and from then on I could never drink it again! Oddly enough, when in evaluation for psych meds, they never asked me about my alcohol use or I would have told them of my allergy. Still, they would have kept with their playbook and prescribed those evil drugs. Maybe, LSD might be good for some alcoholics, but I still question if it is of benefit to others or even it might be dangerous to others. We usually forget how individual our unique systems are. We are created to be unique in almost all sense of the word; despite so much we do share as humans. It is one of those both complex and simple paradoxes of life that many want to forget because so many professionals in so many areas just want to take the easy way out—one size fits all or even most. But life is not one size fits all or most. It sure would be boring and nearly unlivable if it were. Thank you.

Report comment

You can start to sort your subjects via testing their perceptual stability, one of the easiest ways being the HOD test, which is quantitative. The folks with unstable perceptions are more likely to bum or freak out than people whose perceptual worlds are more stable.

Many years ago, I had an illustrative experience that demonstrated this. Some young chap at the center where I volunteered, wanted to take LSD, but he wanted to take the test to see if this was a good idea. His score was very high, as though he were tripping already (he wasn’t), so I told him he was high risk and I wouldn’t supervise (guide?) his upcoming trip unless he took 3 grams of ascorbic acid (vit. C) per day for several days prior to his voyage, so he wouldn’t lose his marbles and jump out a window.

He didn’t take the C but did drop the acid and had a miserable time, finally telling me in an embarassed voice that he’d jumped out of a window in his house.

Report comment

This is a very interesting and lengthy article and as usual I read it from my perspective; although I realize other perspectives are useful and necessary. My conclusion after reading this article is that yes, there are tragic similarities between “psychadelic” drugs and “psychiatric” drugs. I thought it was uniquely interesting that some may have this visual disturbance from birth. I, too, have had visual disturbances. Some I can say most probably resulted from the withdrawl of the psych drugs. But, I had visual disturbances, earlier even as a child. I, too, could close my eyes and be anywhere I wanted to be—usually it was previously places I had lived or been down to littlest detail. I lost that ability when I was taking all those psychiatric drugs, but, now it is coming back to me. In fact, having this ability, caused the “psychiatrists, etc.” to further describe my entire life in diagnostic and defective terms. In the Bible, there are all kinds of prophets and other who have dreams and visions, such as “Jacob’s Ladder.” I think some may have been gifted with some type of this so that would not make it a disturbance at all. I, also, wonder if maybe those who try to get this “gift” by “chemical means” do suffer disproportionately. That doesn’t mean that taking either psychiatric drugs or psychadelic drugs does not cause suffering. In fact, taking these types of drugs, will eventually cause some type suffering for everybody at some point in their life, so I say, stay away from these drugs no matter who you are. In the end, I will react to these drugs and the side-effects, after-effects, etc. of these drugs’s usage is still highly individual. This true individuality will always confound the efforts of many in scientific research. It will also throw out the fires of the lies of being a global citizen. That is because each of one is here to contribute with our unique individual talents and gifts to help others with their individual talents and gifts. Psychiatry, with or without drugs and therapies, etc. misses that completely. Until we accept that truth, we will suffer. Thank you.

Report comment

Just in from the rain and I read your dazzling article, Mr Prideaux. I am astonished at your succulent descriptions. You must surely be a star novelist? And I hope you do not mind my saying so but as an occasional artist I feel that your bone structure has a likeness to a very young Vincent Van Gogh. There is one photo of that man in sepia. Vincent looked remarkably different to his older portraits when he was at a tender age. I dare say that schizophrenic voice hearer partook of ergots in summer rye fields. His lush paintings may have been enhanced by HPPD.

I found your article to be beautifully balanced overall. An exploring manner. I do empathize with some of what Steve feels concerned about. But I am not sure you were being an advert for the medical use of psychaedelics. I think you were trying to pull in various possibilities into the much needed discussion.

I myself am not at all into drugs. I feel that altered states of consciousness are why we have clouds and rain and pine forests. For me, to belabour my poor brain with substances to shake up special effects would be as artificial an impressive delight as cgi computer effects. But I know a few devotees of inward journeys who would be miserable without such happenings.

I do wonder if the mass intake of street drugs may be causing so many youths post-high slumps and derealization episodes that get blamed on misbegotten parents. If the effects you speak of do cause a traumatic level of alienation in many then that year long delayed jumble of sensations and moods and flashbacks, that amounts to “trauma”, may be wrongly and increasingly laid at the innocent feet of perfectly ordinary moms and dads.

On that matter perhaps you chose to call your article by a title flagging up chemicals rather that trauma because you recognize there is sometimes a difference to be made between things going haywire in the brain and things going haywire in childhood.

There seems often a blurring of these into one godforsaken travesty. And possibly there is a great deal of truth in that for many. But not all.

You make parallels with schizophrenia and I found it refreshing to read an article that is not scared to consider the notion that consciousness can slip and slide in ways that may have nothing to do with a family divorce.

I have long felt my schizophrenia to be similar to epilepsy. I honestly can’t help it. Just like you cannot help having visual disturbances.

I doubt a trauma focused session or two would resolve something that is as beyond control as the is the sensation of an intolerable life-sapping never ending itch.

I feel there should be two forms of healthcare in the future. One for people who prefer to find healing in trauma focused regimes, and one for people who prefer a more medical approach. The difficulty with the medical approach is them science boffins are ever wont to come up with barbaric physical treatments. Bad treatments. Especially of the most precious organ.

In the medieval epoch there were apothecaries, ergot purveyors, and astologers, and herbalists, and rune casters, and chicken bone oracle diviners, and cabbage leaf readers, and nuns and monks with nice soups. But there were also leeches and cupping and that early form of self harm known as bloodletting, and there was the placebo credentials of having prayer said for you, and there were consultants in bodily humours. My fav. The humours related deeply to temperament so you could say they were a forerunner of psychiatry. A marraige of bodily understanding and how it may affect the mind or consciousness.

Every civiliazation has had to enshrine its “certainty” somewhere. It comforts a society to think it owns certainty. In the medival era that certainty was gilded and propped on an ecclesiastical altar. Because it was all taken care of there, by the imperial Church, it meant that other professions did not have to be quite so certain. They could make things up as they fumblingly went along, learning in a natural trial and error way. But in modern times, with the dismantling of the altar, “certainty” had to find a new home, with the Gods of Science.

I think there is nothing wrong with UNCERTAINTY. It is great for any profession. But when a profession gets toppled for doing too many mistakes, the successor profession can claim “certainty” in a way that is not an improvement but more like more of the same.

So I like your UNCERTAINTY. It is pleasantly medieval.

By the way, if you click on my name you may dig up a comment I made to Peter Gotcheze recently about my visual disturbances. For me they relate to phone use. The flicker rate in computer screens sets it off for hours, days. The image you produced looking down at the ground is similar to what I saw on my wall. The rate of ever morphing spasms of light like a strobe is similar.

In my ow understanding it is caused by my having a super sensitive brain. Some people are just not able to deal with not living in a remote leafy glade with beautiful tranquil peace all around them. Epileptics have super sensitive brains that can be set off by stimulus such as noise, pattern, light. I suspect our global use of smartphones is setting off the brains of the succeptible. Profound and shockingly sudden falls into brain fog episodes are the worst aspect. You cannot spark two thougts together. Something you might have thought was derealization or depersonalization.

I could say try no phones or laptops or computers or television or disco or sunlight for a month….but

look at me now. Here I sit day after day typing on a tiny bright screen like it contains my brain. Really it is a brain tumour held in the hand and endlessly scrolled.

Anyone for painting?

Report comment

“How should Psychedelic Medicine Handle Flashbacks?”

By not consuming the Psychedelics to begin with.

When I came off Long Acting Injections I suffered from a type of chemically induced Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome; and this Syndrome nearly drove me back onto the Injections.

But then I gained some insight: I could see – that while I was very concerned with whatever I had on my mind ‘at the time’ – I was Okay with what had ‘really bothered’ me ‘the day before’. I was then able to see that if I could allow whatever problem I had ‘at the time’, to go to the back of my mind – that this problem could become ‘Okay’ as well.

(Then I could eventually see that there were NO real problems)

I would imagine that Approaches that “Work” for “Schizophrenic Drug Withdrawal” – could also “Work” for “Schizophrenia”.

Report comment

Fair point but unfortunately none of it works for the iatrogenic travesty that is chemically caused schizophrenia, a damage that too many now know they have and continue to feel hurt by. So I doubt it works much at “fixing” or “getting rid of” real schizophrenia either. However what drug withdrawal does do really beautifully is cease the brain shrinking chemicals that do not seem to be helpful at all for lots of people….

I imagine.

Report comment

Is there really a distinction between drug-induced schizophrenia or “real” schizophrenia or ny other alleged psychiatric DSM diagnosis? I wonder, as all my diagnoses came after I was drugged and therapized and the diagnoses left me when I walked away fro the psych world and stopped the drugs and therapizing. And, when I got off the drugs and therapizing, I realized partly what they were punishing me for with the drugs, etc. were my natural God-given strengths like my imagination, for instance. I guess you could say that this is a disconnect. Yes, and a various dangerous one at that. Like the old commercial, said “This is your brain on drugs.” What the makers of that commercial didn’t realize that what psych drugs do the brain makes it look more like an EF 3, 4, or 5 tornado or hurricane than just a fried egg in a frying pan. Thank you.

Report comment

No, as megavitamins B3 and C will frequently appropriately treat both “real” and drug-induced schizophrenias, which you’d know, were you into orthomolecular medicine.

Report comment

This is a fascinating article, and it’s really helping me to broaden my view of the range of what’s possible within human consciousness and perception. Also fascinating are the long and well-thought-out responses. It’s a conversation I’m really interested in. Is there any such thing as “normal” experience? How much difference does our attitude make when our perceptions go outside the range of our previous experience? I’m going out on a limb to connect the ideas in this article with my own philosopy of healing through self-acceptance.

I don’t actually have experience either with taking psychedelics or having perceptual distortions, but I have been making my own journey of healing from childhood trauma and delusional thinking, after decades of frustration with therapists and drugs that didn’t help out with the chaos going on in my mind.