At age eighteen, in the summer of 1962, after the last of a series of four minor traffic accidents as a passenger, my mind, not my body, shattered. When the slow-moving pickup truck rear-ended my father’s Plymouth at a stop sign, I dropped to the floor of the back seat of his car curled up into a fetal position, rocking back and forth, fearfully chanting, “make it go away… make it go away… make it go away.”

Growing up in my family home, I was both witness to, and the subject of, raging anger, physical assault, and sexual abuse. Contrasted with that was smother-love and religious teachings. In addition, I experienced emotional neglect, abandonment and hypocrisy. However, the family presented well in public.

A history of violence, abuse and trauma ill equipped me to bear the ordinary pressures of adolescence and young adulthood. Something had to give. I did, in the back seat of my father’s car.

For the next seven years I was diagnosed with four different varieties of schizophrenia by as many different medical model psychiatrists. Treatments ranged from near lethal doses of psychotropic medications, to failed shock treatments, to almost continual short and long-term hospitalization in public and private hospitals.

My feelings of despair, confusion and fear drove me to self-destructive behaviors, including frequent and serious self-injury and suicide attempts. My inability to communicate effectively with words, my lack of impulse control, and my powerful unmet need to love and be loved only served to bring more chaos and rejection to my life.

In 1971, I was sent to the UCLA Emergency Room to be treated for a particularly lethal suicide attempt. The psychiatrist had me transferred to the ER at Saint John’s Hospital in Santa Monica. As I was lying on a gurney in their ER, feeling spent, Dr. Joseph Jones greeted me. He said, “Hello, I’m Dr. Jones. What is your name?” I didn’t speak, feeling indignant that he ought to know that. He looked me in the eyes with concern and interest. He said, “What happened to you?” I barely answered, again feeling put upon. Finally, after a few more words between us, he said, “I would like to admit you to the hospital. Is that alright with you?” I didn’t speak.

I was put on a 72-hour involuntary commitment hold, and taken to the locked psychiatric unit. While I was there, Dr. Jones came to see me every day for at least fifty minutes. He took me off the locked ward and we walked to a small office in the open ward. After each session he told me what time he would be back to see me in the morning the next day. He was always prompt. The staff laughed at me when I told them I had an appointment at 9:30 or 10:10 or 11:00 with Dr. Jones. But there he would be, right on time to talk with me.

Other doctors came to see their patients at random hours of the day or night. Patients never knew what activity would be interrupted. The average visit with a doctor was between five and ten minutes. You never knew when they were coming back.

The sessions with Dr. Jones were moving me to a new place in my being. Dr. Jones not only demonstrated respect and courtesy with his promptness, he did it in spite of the staff’s mockery, which demonstrated to me his integrity. He didn’t tell the staff his arrival time. He told me, as if I was a person worthy of his consideration and it was between him and me to know this bit of information.

Who was this man whose ethics and compassion seemed impeccable? Why me? I felt myself to be a wretched alien specimen not worthy of anyone’s time or energy. In fact, I worked at being a rock, as in the Simon and Garfinkle song “I am a Rock” — “I touch no one and no one touches me.”

I learned that he was the head of the inpatient unit and the day treatment program at St. John’s. He was down to business, but in a brilliantly plainspoken, direct, sincere and deeply empathic style. He had been a corporate attorney before he became a psychiatrist.

The initial meetings with Dr. Jones astonished me because of the gentleness and caring he showed through his words toward my unhappiness and me. He conveyed a depth of understanding of my despair and pain. What I had hidden deep within my soul, he articulated for me in terms that resonated, touched and astounded me. I thought maybe this was the psychiatrist who might be able and willing to help me sort out and bring enlightenment to the chaos of my life.

Later, during my hospitalization, he took me off the ward, through the hallways to his office downstairs. It was a demonstration of his trust in me and I began to trust him and what he said. Finally, I was privileged to walk off the unit to his clinic office on my own.

I was hours away from discharge, on a Friday afternoon, with a terrifying long weekend in front of me. I was to begin the day treatment program on Monday. Having come to the last minute, I asked him the riskiest question of my life. The risk was another rejection, another hopeless point. But I said, “Will you be my doctor when I leave?” “If what?” he said. I did not understand. “What do you mean?” I asked. He repeated, “If what?” Again, I asked him what was he asking me. I was perplexed and annoyed.

After more banter back and forth, something struck my mind. I didn’t want to say it. It would mean a commitment and a concession, a rule I couldn’t break no matter my pain. Because he would trust me to carry out an agreement between us, I would be obligated to this human to endure.

The next time he said, “If what?” I heard myself saying, “If I don’t suicide when I leave?” He looked at me and as I looked down, I saw him nod his head. A few hours later, as I walked out the door of the unit with an appointment card in my left hand, he smiled and said, “Good luck.” And Dr. Jones, my first real doctor, shook my right hand.

Dr. Jones spoke to me in a way no doctor ever had. His affect, his demeanor, his presence, lit an ember in the darkness within my soul. I was like a lost puppy, hungry for time, attention, and to love and be loved.

A conflict took seed in me. It was between my morbid, nihilistic, self-mutilating, suicidal self and the wisp of hope I felt from this man. Was I a dead rock or was I becoming alive to feelings?

Having struggled to survive the weekend, I went to my 10:10 a.m. appointment in his private office in Santa Monica, intact but scared. My desperate need overcame my fear of feeling.

He had rules that were conditions to our time together. He said therapy would be no less than two times a week. He couldn’t do psychotherapy properly less than that. And many times, over the years, I met with him as much as three, four, five, even six times a week. He said that therapy went on 168 hours a week, and that I was to be involved in the work of therapy during those hours.

I agreed that I would not take any psychotropic medications for the duration of my psychotherapy with him. Dr. Jones said medications interfered and distracted from the therapeutic process. No matter how difficult or painful, I withstood without relent. I took no pills. Others would urge me to medicate, “just a little to take the edge off,” they would say.

Because I spent the majority of 168 hours a week submersed in the inner world of my past, outer reality became vague and dim. I was frightened to do anything to destabilize my mind. The process I was going through with Dr. Jones had left my hold on reality tenuous enough.

This was an era of burgeoning street drugs: opiates, barbiturates, amphetamines, hallucinogens, all readily obtainable. I was interested in none of it. My immersion into my inner world was too intense and my commitment to this man’s process too compelling to risk my life in that way.

I continued to do the new therapy process with Dr. Jones even though I still felt hopeless as a person and doubtful of the use of this psychotherapy. Dr. Jones proceeded cautiously, as if he had hope. His perspective buoyed me enough to keep up my part of the agreement we had made. And besides, at least I had the pleasure of his company several times a week.

Being with him became my prime motivation for working in psychotherapy. His ability to use ordinary words to convey complicated feelings, ideas and information awed and pulled me closer to him. He seemed dedicated to fathoming my depths. My job, according to him, was “to say, without hesitation or censorship, anything that comes to mind.” He wanted me to report rather than reason, detail not summarize, and describe without interpretation.

There were probing questions that had me reach into my mind, my memory, myself at the core of my being, to find answers. I was to stay with a feeling as long as it took to experience it to its fullest. Nothing was to distract me from this work. Not people, places or things. I experienced searing, molten pain and transcendent pleasure practicing his method.

I suffered all this pain and misery not so much because I hoped that it would work to fix me, but for the pleasure of his company. To be with him day after day, week after week, month after month was all I lived for.

I allowed his dedication, hope, and wisdom to guide me. Of course, I was projecting and steeped in transference, to use psychological jargon. But in my soul, something was happening that changed my life. I had what I call an epiphany, an awakening. I cannot pick a moment in time and place, like the apostle Paul, but it was during an era of my time with Dr. Jones. The shattering stopped, the essence of my being was bare, and the reorganization began. “I” came into being from the depths of existence as a near corpse.

Dr. Jones began to limit my contact with him. I began to feel a change in our connection. There was the beginning, what I call the introduction or perhaps the tender trap. The middle was filled with pain, primarily, and concluded with the epiphany. Termination took five years. It was remarkably slow to come. The pain of the separation took another twenty years with an assortment of therapists before the intense grief stopped interfering with my functioning.

But I am here now with you, present in a way that that man hoped I would be.

I would ask him if he thought I was a hopeless case. He said he didn’t think of people as hopeless. He thought people had hopeless feelings and that those feelings could change with psychotherapy. He would tell me that I had to stay with the feelings without distraction until they changed. “Feelings always change,” he said. Then I asked him if he thought I would suicide. He said it depended on how many hopeless feelings I had.

I did not understand how to connect and process those words into meaningful action at the time. I see now that I was lucky enough to be able to stay with enough hopeless feelings long enough to survive. The hopeless feelings did change. I was able to endure the pain until they changed and relented.

In the beginning of therapy, I said that “the only thing I learned from my mother was how to endure misery.” As I had watched her suffer and bear her existential pain without doing something different to change the source of the terror, I absorbed her survival strategies and techniques. What a mystery are the gifts we’re given.

Dr. Jones always said it was a programming or software problem, not a hardware or biological problem that was causing my misery and suffering. I understand that now, too, in a deeper way. And I realize that without his offering of his persona, persistence and perception, I might never have found mine.

The dawning of life to my deadened soul through the intense human connection I felt with Dr. Jones was the key to my presence here with you today. It is this kind of life that the psychiatric medical model of brain chemistry, with its superficial behavioral dogma and distancing of who we are from one another, can never hope to achieve.

“To love another person is to see the face of G-d.” — Herbert Kretzmer, lyricist, Les Misérables

What an amazing ‘success’ story and such a needed narrative! The public needs to understand that a radical change in psychiatric ‘therapy’ is the only way to help those suffering from the traumas that we inflict on each other. I wonder if the scientific/materialistic methods will ever truly be wiped out. These only seek to understand the ‘mind’–not the workings of the ‘heart’ and the depths of the ‘soul’!

Thank you, Lynne Stewart!

Report comment

A doc refusing medication as treatment and insisting on talk therapy, and then also insisting that therapy must come to an end?

How rare is your story, not or then?

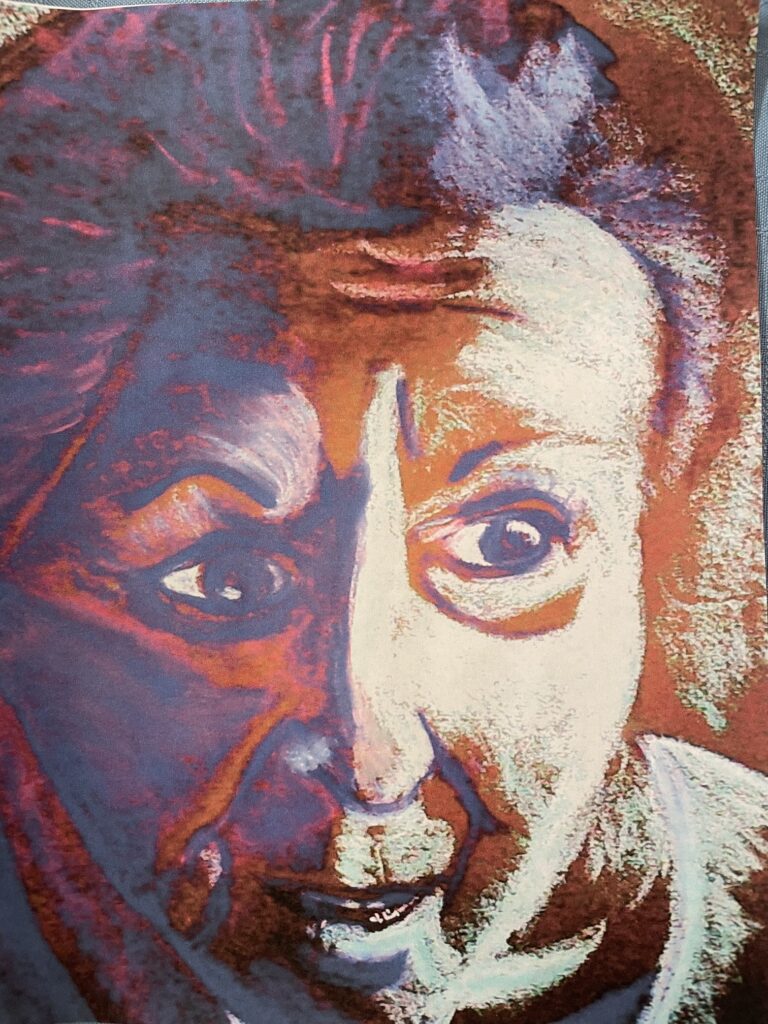

Thank you for sharing your story and artwork.

Report comment

Lynne, thank you for this articulate and beautiful story of your experience. It is the relationship that promotes healing, strength and change, no question. And both people make that happen. And by the way, I have no doubt that Dr. Jones grew and changed because of your intimate and profound relationship. How could it be otherwise? Thankfully, the old models of ‘termination’ and so on are not a given in contemporary psychotherapy. Each individual is a world and so therefore is the clinical experience and relationship. Bless you!

Report comment

Good one

Report comment

Thank you Lynne, for telling your story. I found it very moving.

And I’m so happy your experience with psychotherapy worked for you. It sounds like Dr. Jones was an exceptional human being. But so are you!

Thank you again for sharing your remarkable story.

And I love your artwork!

Report comment

Dear Lynne,

Thank you again for your moving story. It’s beautiful and poignant. And I’m really glad you had such a fine person to help you. It’s my wish that more people could be like Dr. Jones. If there were, there’d be no more “mental illness”. And I believe it can happen, one person at a time.

And I’m looking forward to reading your book, “On Becoming Human: A Memoir –

Report comment

Wow, crux of the many articles that launched my curiosity. Meds.or an astute Dr. to treat through psychoanalysis.

Very clever description of programming/software vs…..

Lynn was very fortunate to have been correctly diagnosed and treated.

You mean 600mg. Thorazine would not do. Just kidding of course.

Sounds like a autobiography in the making. Promise I would read it. Cheers and hats off to Dr. Jones.

Report comment

Thank you, all, for your comments, support and encouragement. Even just the few comments gives me heart to carry on carrying the word to others. Yes, I do believe benevelent, deep communication is essential to substantive healing. When will they ever learn… those medical model (the physical brain) doctors.

Report comment

Lynne, I’m so glad you gave up the notion to commit suicide so we could all learn from your success.

Good article.

Report comment