“I withered in the following regimen: padded cell. Injection to sleep. Violence from the orderlies. Padded cell again. More violence from the orderlies. Padded cell (sometimes sleeping on the cold cement). And so on. Escape.”

In her 1965 memoir, Hospício É Deus, Brazilian writer Maura Lopes Cançado recounts the daily routine of abuse, forced medicalization, isolation and humiliation she suffered in several psychiatric hospitals.

The book, a pioneering work denouncing asylum conditions in Brazil, is filled with many more harrowing accounts of the mistreatment inflicted on patients in the many institutions where Lopes Cançado resided over the course of her life.

She describes doctors, nurses and orderlies using electroshock therapy as retaliation against patients, including herself, despite her prior history of epilepsy being a contraindication. Orderlies berating and humiliating patients. Frequent solitary confinement imposed as punishment. Sedatives administered without necessity. Chronic hunger and cold. She even mentions a psychiatrist who, upon interrupting her session with another doctor, diagnosed her with a “psychopathic personality” without having ever addressed her directly.

“It’s sad to know that our struggles are met with such indifference,” she writes. “Just another patient given shock treatments, shut away in the padded cell, and other things.”

Sadly, her experiences were all too typical in Brazilian psychiatric institutions. The reality for most patients was disrespect, indignity, violence and neglect; and as most forms of cruelty perpetrated against living beings, such abuses were made possible only by the systematic dehumanization of people with mental illnesses.

Places of exclusion

Philosopher Michel Foucault, in his instrumental work Madness and Civilization, traced the origins of the modern asylum to institutions of exclusion, built to segregate non-working or deviant individuals from productive, law-abiding society. Institutionalization, he writes, “isolated from the working populations those who do not work, the ones who do not belong, who do not obey economic norms”.

Over the centuries, psychiatric institutions shifted into prison-like environments, conflating madness with criminality or deviance to justify the alienation, control and surveillance of people with mental illnesses. Supposedly therapeutic interventions aimed at recovery devolved into horrific, torture-like practices inflicted on hundreds of thousands of people.

Such practices were commonplace in Western societies. In Brazil, perhaps the most infamous example was Hospital Colônia de Barbacena.

Operational from 1903 to the 1980s, Barbacena was the site of unspeakable atrocities committed against psychiatric patients. The hospital housed more than 5,000 patients – well over its capacity of 200 – who were continuously subjected to violence, torture, sexual assault, neglect, malnutrition, hypothermia and disease. With no indoor plumbing, many patients drank and bathed in open-air sewers.

By the time the hospital closed, it is estimated that over 60,000 people had lost their lives within its walls. The carnage was such that the local cemetery couldn’t accommodate the number of bodies – so hospital staff sometimes smuggled corpses to medical schools for profit. If demand was low, patients’ remains were dissolved in acid.

Psychiatry for political oppression

The tragedy in Barbacena was dubbed “the Brazilian holocaust”, but its infamy extended beyond the chronic abuse of patients. As many other asylums, it became a notorious instrument of political control, often referred to as a dumping ground for society’s undesirables.

“The culture back then was that anything that was a nuisance got sent to Barbacena,” recalls psychiatrist Jairo Toledo, who was a medical resident at the hospital in the 1970s, in an interview with newspaper Brasil de Fato. “And it wasn’t just the so-called ‘mental patient’ – they sent the medical patient, the drifter, the ‘social problem.’”

Roughly 70% of patients at Barbacena had no psychiatric diagnosis – they were people with substance abuse problems, single mothers, unhoused or undocumented individuals, people of color, sex workers, queer people and political dissidents, sent there by governments and elites brazenly attempting to erase marginalized groups from society.

The problem only worsened when Brazil entered a ruthless military dictatorship, which ruled the country from 1964 to 1985. One of its primary concerns was the silencing and disposal of political dissidents, an effort in which psychiatric institutions were plainly complicit. An investigation by news website UOL discovered 24 cases of political prisoners who were sent to psychiatric hospitals, 22 of whom were first subjected to torture in prison – but the true number is likely much higher.

Early reformers

The status quo of psychiatry was fortunately not without detractors. One early example is Dr. Juliano Moreira, Brazil’s first Black psychiatrist and a pioneer of psychiatry and psychoanalysis. He was an outspoken advocate against racism in the medical sciences, refuting a commonly-held belief at the time that miscegenation caused mental illness. In 1903, as an asylum director in Rio de Janeiro, he made significant strides to humanize treatment by abolishing straitjackets and removing bars from the windows.

But perhaps the most renowned figure in Brazilian mental health activism is Dr. Nise da Silveira. A radical dissenter from the psychiatric establishment, Nise steadfastly rejected violent, invasive practices that objectified and oppressed patients.

Her alternative was much more compassionate and creative: an occupational therapy atelier where patients could paint, sculpt and interact with cats and dogs she affectionately called “co-therapists”. The interactions between patients and animals encouraged emotional bonds, responsibility and autonomy, and the practice of art helped patients process emotions and traumas they couldn’t express any other way.

One of her patients, Lúcio Noeman, became known for his detailed and sophisticated clay sculptures, depicting mythological warriors as stand-ins for internal conflicts. His work was even exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art in São Paulo, and Nise’s workshops significantly improved his condition.

However, Lúcio was still considered a “difficult” patient, and his family doctor insisted on a lobotomy. Nise warned: “You’re about to decapitate an artist.” She was right – the lobotomy annihilated his creativity and artistic abilities. He lost all interest in sculpting, producing only crude, misshapen works – a disturbing mirror of his own deteriorating mental state. He lived the rest of his life in apathy, stripped of all artistry and agency.

From asylums to communities

Across the Atlantic, another psychiatrist would go on to make an indelible mark: Franco Basaglia, who in the 1960s revolutionized psychiatry in Italy by championing deinstitutionalization and the reintegration of patients into society. Like Nise da Silveira, Basaglia was horrified as a young doctor by the conditions in which patients were forced to live and refused to conform to the prevailing norms of psychiatric practice.

Basaglia was among the first mental health professionals to acknowledge that many of the stereotypes of madness – baffling, deranged, irrational behavior, all that can be dismissively labeled crazy – are not inherent symptoms of mental illness, but products of the asylum environment itself. Patients learned to “act crazy” in response to the cruelty and indifference they were shown. At the same time, their widespread confinement only aggravated social stigmas, suggesting to the public that people with mental illnesses were dangerous, untrustworthy, prone to violence and incapable of participating effectively in society.

For Basaglia, it was clear that social isolation, stigmatization and indignity in institutions did not help recovery, but actively hindered it. Thus, he called for the complete closure of asylums and their replacement with subject-centered treatment centers that reintegrated individuals into their communities, first implemented in the city of Trieste. His approach proved so effective that it became a global reference point, and it was adopted across Italy following the enactment of the Basaglia Law in 1978.

The birth of Brazil’s anti-asylum movement

Basaglia’s success in Italy inspired psychiatrists in Brazil who were equally dismayed by conventional psychiatry. In 1978 – when the Basaglia Law was passed in Italy – the Brazilian anti-asylum movement began to take shape. The military dictatorship was weakening: censorship was waning. Exiles were returning. Dissidents were speaking out more boldly.

But the dictatorship wasn’t over yet, and its influence was still felt within asylums. Political prisoners continued to be incarcerated in psychiatric hospitals, recalls psychiatrist Paulo Amarante in an interview with Radis Magazine. “There were psychiatrists involved in the torture and disappearance of political prisoners – at the [asylum] Colônia Juliano Moreira, there was a ward into which only the military could enter.”

Amarante, one of the forerunners of the anti-asylum movement, was also among the first to publicly defend the rights of psychiatric patients and decry asylum conditions. But this advocacy resulted in his dismissal, along with two colleagues. “Eight people, among them [psychiatrists] Pedro Gabriel Delgado and Pedro Silva, organized a petition to support us,” Amarante said. “Later, another 263 people were fired. This gave rise to a movement.”

Despite the repercussions, Amarante, Delgado and several others carried on the fight. That same year, activists stormed the Brazilian Congress of Psychiatry, where respected physician Luiz Cerqueira pleaded to include the anti-asylum struggle on the official agenda. Amarante created a self-published newspaper about the movement and distributed it to mental health workers outside hospitals, as he was barred from entry.

‘78 also saw the creation of the Movement of Mental Health Workers (MTSM), composed of professionals, former patients and family members, which mobilized activists and spurred collective action. Later, community TV and radio projects, such as TV Pinel, were created to report on mental health issues and provide a platform for patients, centering the narrative on them as political actors.

Another turning point came in 1979, when Franco Basaglia visited Brazil. During this trip, a group of psychiatrists invited him to Barbacena, hoping his voice could amplify the cause. Shocked by what he saw, Basaglia famously compared Barbacena to Nazi concentration camps.

Psychiatric reform made law

After nearly a decade of relentless activism, the movement hit another milestone in 1987. Two years into Brazil’s newly restored democracy after 21 years of dictatorship, the first-ever Center for Psychosocial Attention (CAPs) opened, an outpatient facility for people with psychiatric illnesses modeled on Basaglia’s community centers. CAPs would later expand nationwide, becoming a cornerstone of psychiatric reform.

The New Republic also brought a crucial political breakthrough. In 1988, a new constitution guaranteed healthcare as a universal right and established the State’s duty to provide it. This led to the creation of the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS), which provided the stable federal funding necessary to implement psychiatric reform across the country.

With constitutional backing secured, in 1989 Representative Paulo Delgado (brother of psychiatrist Pedro Gabriel Delgado, a leader in the anti-asylum movement) introduced a bill to enshrine deinstitutionalization in law and to guarantee the rights of people with mental illnesses.

The bill languished in Congress for twelve years, but in April 2001, it became law: under the Psychiatric Reform Law, asylums would gradually be dismantled and replaced with a national network of public mental health services.

Deinstitutionalization in the U.S.

A separate push for deinstitutionalization was underway in the U.S. during the 1950s and 1960s, initially fueled by journalists, activists, former patients and family members exposing inhumane asylum conditions.

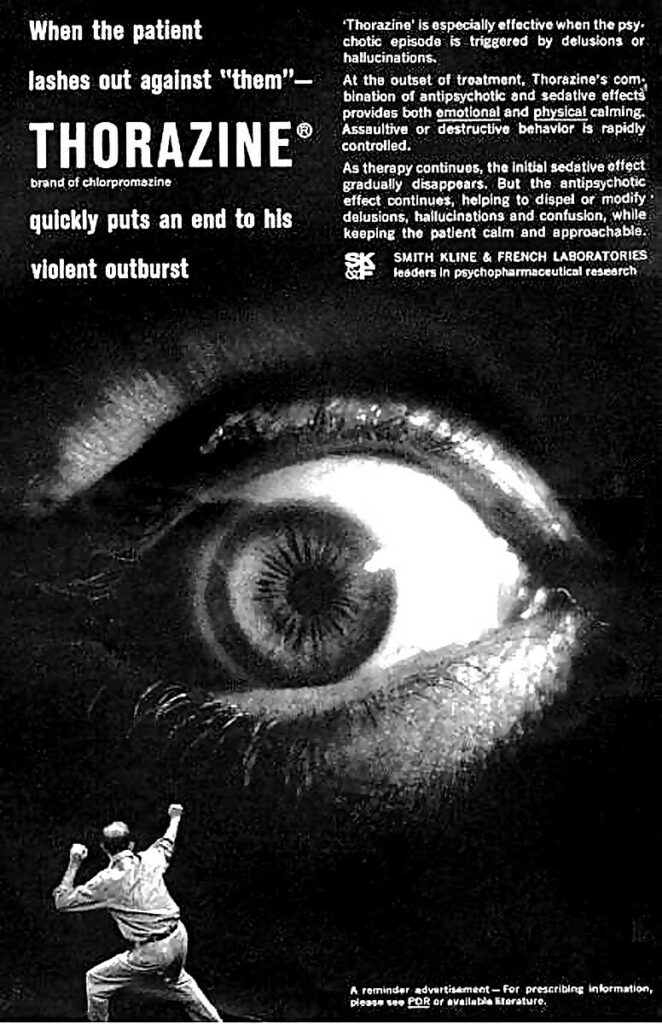

Unlike Brazil, however, these concerns never coalesced into a fully fledged activist movement, and human rights were only one part of the equation. The push also stemmed from a desire to cut costs and the rise of pharmacological treatments. State-run hospitals were expensive, and economic conservatives seized on deinstitutionalization as a way to reduce spending. At the same time, new psychotropic drugs promised to manage psychiatric symptoms more effectively and cheaply than long-term institutionalization.

The growing shift in public opinion was embraced by President John F. Kennedy, who signed the Community Mental Health Act in 1963, just weeks before his assassination. The law promised federal funding for research facilities and community mental health centers aiming to replace asylums, a vision similar to Franco Basaglia’s.

But despite good intentions, the Community Mental Health Act ultimately failed. Around 1,500 centers were planned, but only half were built. The act also included no long-term planning, leaving the centers that were established without sustainable funding or staffing, fragmented and under-resourced until they fell off the political agenda altogether.

Consequences

As a result, the mental health system in the U.S. is now functionally broken. According to NPR, two-thirds of people with mental illness do not receive adequate treatment, often because insurance coverage is denied.

As access to care becomes increasingly limited, incarceration rates for people with mental illnesses have soared. Law enforcement commonly responds to psychiatric crises with arrests, creating a system in which prisons have effectively replaced asylums. Today, 43% of people in U.S. state prisons have a psychiatric diagnosis, 33% of whom have not received treatment since admission. And since racial profiling is a persistent problem in psychiatry, people of color are more likely to receive serious psychiatric diagnoses, and thus more likely to face incarceration for mental health issues. Many others become homeless, with a recent study finding that 67% of people experiencing homelessness had a mental health disorder.

The ensuing mental health crisis in the U.S. has led many critics to blame deinstitutionalization, as though it could have been avoided had asylums remained open. But this assumption misses the point: the failure was not the closure of psychiatric hospitals, but that the goals of deinstitutionalization were misguided from the start.

Fiscal conservatives viewed mental health initiatives as an economic burden, given the low capital productivity of asylums and patients. They were not interested in the civil rights of people with mental illnesses, nor in guaranteeing adequate, humane psychiatric treatment – their aim was purely to cut costs, which means that appropriate public funding was never going to be allocated to better forms of psychiatric care.

The push to replace asylums with medication was also problematic. This effort, a profit-driven narrative perpetuated by pharmaceutical companies, appeared to offer a simple solution to a complex problem: a fast and cheap way to subdue – not treat – mental illness, eliminating the need for any kind of long-term therapeutic care.

This only succeeded in erasing mental illness from the public eye without addressing any root causes such as trauma and socioeconomic stressors. Framing mental illness strictly as a medical disease or chemical imbalance removes patients from being active participants in their own recovery, and it lets society off the hook for confronting the uncomfortable subject of madness. Overmedicalizing mental illness became yet another mechanism of exclusion and control that happens in plain sight, but in silence.

A public mental health network

Nise da Silveira initially feared that deinstitutionalization in Brazil would lead to a similar outcome. As Paulo Amarante explained in an interview, she worried that after long hospitalizations, patients would not have the social or vocational skills to thrive in society, and that without asylums, they could become vulnerable to violence, abuse and neglect.

Yet she later supported the anti-asylum movement when she realized its goal was to provide care outside hospitals while also empowering patients to build lives with autonomy and dignity. Thanks to this, a different system took shape in Brazil.

After psychiatric reform became law, a Psychosocial Care Network (RAPS) was created within SUS, tasked with directing patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders to the appropriate public services. To gradually replace psychiatric hospitals, additional Centers for Psychosocial Attention (CAPs) opened across the country, with as many as 3,343 as of 2023. At these centers, patients receive mental health care, including in crisis situations, as well as eat meals, get haircuts, practice sports and develop vocational skills such as sewing, carpentry and IT.

Other RAPS facilities include therapeutic residences, which provide housing for people with mental health or substance use issues without a steady income or support network, and supportive housing units, which temporarily shelter people at imminent risk of violence or neglect. In addition, multidisciplinary teams – comprising psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, speech therapists and other professionals – work in outpatient clinics and hospitals as part of the network.

The law also prohibits forced hospitalization without patient consent. Only in the most severe cases, when outpatient care fails to achieve the goal of reintegration, can patients be referred for short-term admission in general hospitals, instead of psychiatric hospitals. Even then, hospitalization is only possible with a medical report or in cases of extreme urgency, such as when the patient poses a threat to themselves or others.

The work continues

However, the work begun by the anti-asylum movement is not yet finished. There are still 16,326 beds in public psychiatric hospitals in Brazil – a decline compared to 2013, but the number of beds in private hospitals has increased. The use of psychotropic medication has risen by more than 50%.

In addition, access to mental health care is still vulnerable to political whims. During Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right administration (2019-2022), the psychiatric reform faced renewed threats through privatization, defunding and rollback attempts. In 2022, for instance, the Ministry of Health under Bolsonaro revoked financing and subsidies for RAPS, diverting R$10 million (roughly US$2 million) in public funds to private asylums weeks later.

It also removed funding from public psychosocial programs and redirected it to private evangelical therapeutic and drug treatment centers. These have been linked to serious human rights violations, including child abuse, forced labor and conversion therapy for LGBTQ youth, disproportionately affecting people of color and the poor.

The U.S is heading down a similar path. The Trump administration’s cuts to Medicaid and the imposition of new work requirements threatens to strip millions of access to life-saving mental health services, and some states have embraced funding cuts to community programs in favor of initiatives that make it easier to involuntarily commit people with mental illnesses. Even more alarming are the “wellness farms” touted by President Trump and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. – which, coupled with lower thresholds for involuntary commitment, could easily become forced labor camps.

Such counter-reforms in both Brazil and the U.S. revive the old logic of psychiatric institutions as wastelands for society’s marginalized, implying that people with mental illnesses belong in jail (or jail-like institutions) to be controlled and punished, branded as dangerous and violent even though they are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of crime. Once again, mental illness is conflated with criminality, deviance or idleness, the label of “madness” used to silence, abuse and exploit vulnerable populations – not only those with mental illness, but also people of color, LGBTQ individuals and those living in poverty, all of whom have historically faced higher risks of arrest and institutionalization. Psychiatric diagnoses may once more become instruments of social stigma and political control.

For that reason, transforming society’s relationship with madness is essential for successful mental health activism, even more so than reforming public services. “The idea of psychiatric reform is limited,” Amarante observed, because what is needed is “a cultural reform. It is through culture that people demand hospitalization, exclusion, othering.”

This broader cultural reckoning could have helped mental health activism gain traction in the U.S. Even more important, though, is an awareness of the activism that transformed psychiatry in countries like Italy and Brazil. However, even more in-depth discussions about deinstitutionalization in American media fail to mention the Italian and Brazilian reforms altogether, as though their struggles and victories have no relevance for the U.S. – if they’re aware of them at all.

But the U.S. has much to learn from other countries – even a country in the Global South like Brazil, where mental health professionals, patients and families mobilized for decades with relentless activism, even under authoritarian rule, and achieved concrete results: community-based care, legal protections for people with mental illnesses and the recognition of healthcare as a constitutional right. If there is ever a time to take inspiration from such action, it is when all human rights, including the right to affordable, humane care, are increasingly under threat.

The anti-asylum fight still persists in Brazil, commemorated each May 18th as a reminder that access to mental health care is an inalienable right – not a political tool, not a waste of resources and not a mechanism of control.

Any updates on the consequences for the people who gassed this man to death?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=heAOtMpVEog&t=83s

Sure doesn’t look like things have gotten any better.

Report comment

I don’t understand how bystanders can just stand there with cameras and watch a man die and do nothing. Those police deserve everything they dish out. We need to be at war with “authority” because that’s where it always ends.

Report comment

I understand how bystanders do nothing……they stood and watched whilst I was subjected to an act of torture and did nothing. And then they started doing things to ‘fuking destroy’ me for complaining.

They fall into three categories. The ignorant, the hypocrites, and the enablers (usually cowards).

I won’t go into details of these types but it is the hypocrites who are the most dangerous. The likes of the lawyers at the Mental Health Law Centre who boast of being ‘human rights advocates’ who conspire with the State to conceal human rights abuses with their negligence, and failure to pursue documents they have a right to examine for their ‘clients’, and instead accept “edited” documents where the abuses have been removed. They take their oaths as a cover.

Still, I guess these fools don’t really think things through. It’s their kids who will be living in the vile place they create with their inability to adhere to some sort of standards of conduct. Because when there is zero accountability as a result of State sanctioned cover ups, things are not actually going to improve. Since when did a cover up mean that it never happened again?

Report comment

The “exclusion,” exile, or punishment of people who society can be convinced are “odd” or don’t fit in is a long and painful tradition on this planet and in this universe.

I see it as an almost completely separate phenomenon from the problem of “mental illness.” Being “crazy” is just one of many designations (or labels) that can get one banished, punished, or worse.

In many ways, the real problem of “mental illness” resides among those who do the banishing, punishing and murdering, and not among those who are its victims.

The problem and challenge is in how to strengthen a much larger, more honest, but less powerful group (or population) to stand up for itself against various forms of criminal activities posing as “governments” or “health care institutions.”

This is much less a matter of political or economic ideology than it is of education and personal development. It is often possible to bring more honest sectors of the “police state” (such as the police officers themselves) into a condition where they are willing and able to resist the criminalization of their activities. It is even possible to reform some petty criminals.

But what we all see (and decry) is a very persistent impulse among the ruling classes to use criminal means to solve their “problems” instead of investing in humanitarian alternatives. This is complicated by the fact that the criminals are often quite skilled in using propaganda against their political enemies. If they gain control of the “mainstream” or “corporate” media, as they have largely done in the West, then they can push public opinion in the direction of supporting them, making a mockery of the “democratic process.” This is our condition on Earth today. Most people are very confused and don’t really know what to do or think. It will be a small miracle if the honest survive in the face of this criminal onslaught.

Report comment

It is always incredibly heartening to read and learn more about cultures and histories that don’t often receive the recognition they deserve. This was a great and insightful read, thank you!

Report comment

In an eloquent and well-grounded manner, this article presents an important historical contextualization of the anti-asylum movement in Brazil. It offers an analytical perspective on how collective activism and community participation have transformed mental health care in the country.

By articulating the intersections between social movements, public policies, and human rights, the text reveals a profound paradigm shift toward more inclusive and humanized approaches to care.

This reflection acknowledges Brazil’s pioneering experience and contributes significantly to global discussions on mental health governance and the democratization of mental health.

Report comment

Forgive me if I’m wrong but this REALLY sounds like ChatGPT.

Report comment