Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on our affiliate site, Mad in the Netherlands. It was written by Sandra Kouwenhoven, an expert by experience in the side effects and withdrawal symptoms of antidepressants and benzodiazepines.

Psychological and relational issues often have their roots in childhood and are closely linked to the attachment patterns we develop early in life. The way your parents responded to your needs — whether they offered attention and how — plays a crucial role in shaping your attachment behavior. Exploring attachment theory can therefore offer valuable insights. This article goes beyond the four commonly known attachment patterns and introduces the concept of “subpatterns,” each with distinct characteristics. These subpatterns can help individuals gain clearer insight into their emotional difficulties — either on their own or with professional support — and move toward a more secure attachment pattern.

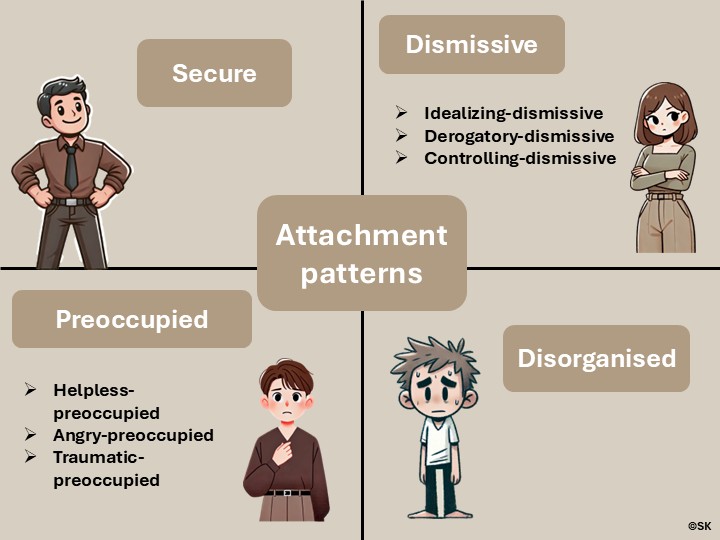

When you read about attachment, it is usually about the four attachment patterns from Bowlby’s theory, commonly known as:

- the Secure attachment pattern (also known as ‘Free’)

- the Dismissive attachment pattern (also known as ‘Avoidant’)

- the Preoccupied attachment pattern (also known as ‘Anxious’)

- the Disorganized attachment pattern

But did you know that there are also subpatterns?

In his book Vrij gehecht (translated as Freely Attached, unfortunately only available in Dutch), Dutch author and relationship therapist Jeroen Hoekman describes subpatterns within the Dismissive and Preoccupied attachment patterns. These subpatterns are clearly distinguishable by their specific characteristics, making attachment theory more concrete and easier to apply in practice—both for personal insight and in therapeutic settings. The subpatterns are derived from the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), a clinical tool used to assess adult attachment patterns.

In this article, I summarize these subpatterns based on Hoekman’s work, using my own words. The Disorganized attachment pattern has no fixed subpatterns, but can show characteristics of all subpatterns.

Subpatterns within the Dismissive attachment pattern:

- Idealizing-dismissive

- Derogatory-dismissive

- Controlling-dismissive

Subpatterns within the Preoccupied attachment pattern:

- Helpless-preoccupied

- Angry-preoccupied

- Traumatic-preoccupied

The four main patterns

Since this article is meant as an in-depth exploration, I assume the reader already has some familiarity with attachment theory and how the four attachment patterns develop. However, to make the article easier to follow for those without prior knowledge, I’ll begin with a brief summary of the key traits of each main pattern.

- The Secure Attachment Pattern:

People with a secure attachment pattern have a positive self-image and feel comfortable with closeness and intimacy. They can process emotional stimuli in a balanced way, without being overwhelmed or pushing them away. Thanks to their well-developed internal base of trust, they are able to feel their emotions and respond to them flexibly. They also tend to be attuned to the emotions of others, communicate openly, and build trust in relationships with ease.

In times of stress, they seek support from others without making themselves dependent, and they can also comfort themselves. As a result, they remain relatively stable in challenging situations. Additionally, they have a realistic and nuanced view of themselves—acknowledging both their strengths and weaknesses—as well as of their past.

- The Dismissive Attachment Pattern:

People with a dismissive attachment pattern often come across as people with a lot of confidence and a positive self-image. However, this is misleading. Their outward independence and strength often mask an underlying negative self-image. People with this attachment pattern tend to let fewer emotional stimuli in, or they actively push them away.

They do not believe that they can count on others and prefer to solve their problems themselves. Their focus is often on achievements and ambitions, with emotional connection considered less important.

In emotional situations, they may respond with short, dismissive answers, change the subject, or avoid (eye) contact. They often ignore their own emotional needs and may find it difficult to enjoy things unless there is a clear goal involved.

- The Preoccupied Attachment Pattern:

People with a preoccupied attachment pattern allow emotions to enter fully but then become overwhelmed. They have a – often openly – negative self-image and seek a lot of appreciation and approval from others.

Because emotions hit them hard, it can be difficult for them to think clearly in emotionally charged moments. This leads to confusion and self-doubt. They often communicate in a detailed and elaborate way but may lose track of their message and come across as unclear.

They are highly sensitive to the absence or emotional distance of important people in their lives and quickly feel anxious when connection feels threatened.

- The Disorganised Attachment Pattern:

People with a disorganized attachment pattern lack trust in both themselves and others. Their behavior is often contradictory: they long for closeness but also feel uneasy with intimacy. This results in a push-pull dynamic—they seek connection and then pull away. They may feel overwhelmed by emotions and panic, react aggressively, or shut down when faced with certain triggers. Their perception of reality can be distorted, as past trauma unconsciously colors how they experience current situations.

Intimate relationships can be complicated by mood swings and unpredictable responses. Often, they are unaware of the traumas that drive their behavior. Rather than processing these emotional wounds, they may have created an alternative reality to cope. As a result, they often find themselves stuck in destructive patterns and may struggle with a deep sense of emptiness

This video by The Holistic Psychologist offers a brief explanation of how attachment patterns develop.

Attachment styles or attachment patterns?

When it comes to attachment, people often talk about attachment styles. In everyday language, this is usually seen as the same as attachment patterns. However, in his book Vrij gehecht (Freely Attached), Jeroen Hoekman makes a clear distinction between the two.

According to Hoekman, an attachment style refers to behavior that someone shows in specific situations or with specific people—it is more situational. An attachment pattern, on the other hand, refers to the overall picture: the typical behavior that stands out when you look at someone’s attachment behavior across different situations and relationships. This distinction matters because everyone shows behavior from all attachment patterns at times. If you only look at how someone behaves in a few similar situations, it’s easy to draw the wrong conclusion. The attachment pattern helps you understand which type of behavior is dominant across time and relationships.

The subpatterns

Within both the dismissive and the preoccupied attachment patterns, there are three subtypes that differ in how people regulate their emotions and express attachment-related behavior. Each subtype shows a different way of dealing with emotional experiences.

Below, I describe each of these subpatterns. Please note that due to the limited length of this article, these descriptions are simplified. The full range of characteristics, expressions, and underlying causes is broader than what is covered here.

Dismissive Attachment Subpatterns

- The Idealizing-Dismissive Attachment Pattern

People with the idealizing-dismissive pattern only allow emotional stimuli to enter minimally and tend to make their own emotional needs seem small or irrelevant. Because of this, others often don’t see their needs, which reinforces a sense of having to cope alone. They often idealize their childhood and past relationships, describing them as better than they really were. Their parents may have been mostly functional—providing things like gifts or material support—but offered little emotional connection. This leads to a denial of emotional pain and a polished image of contentment. In their view, they got everything they needed, without realizing what was missing emotionally.

People with this subpattern may believe they can only be loved by helping or admiring others, leading to a submissive role in relationships. To avoid tension, they adopt a rational, pragmatic attitude and tend to downplay emotional issues—both in themselves and in others. They often avoid asking for help, even when they secretly long for support. This inner contradiction can lead to frustration and isolation.

This pattern is not always easy to spot at first. People with this attachment pattern often come across as helpful and independent, while deep down there’s a lack of trust in emotional closeness.

Over time, this pattern can lead to tension in relationships, feelings of loneliness, and emotional exhaustion from constantly balancing independence with the (unconscious) need for connection. Growth begins by learning to ask for help, trusting others in doing so, and practicing emotional presence in relationships.

- The Derogatory-Dismissive Attachment Pattern

People with this subpattern use a derogatory or mocking attitude to keep emotional stimuli out. The importance of attachment and attachment figures is minimized by being condescending about them. Underneath this behavior lies insecurity and a lack of basic trust in themselves, which makes any form of (positive) dependence feel risky.

They often respond to emotions—both their own and others’—with cynicism, sarcasm, or humor that belittles vulnerability. They may see themselves as more rational or competent than others and look down on emotional expression and dependency. Deep conversations about feelings are often avoided, and painful experiences or criticism are quickly brushed aside.

This pattern often develops in response to a childhood with high expectations, little emotional support, and a family view that vulnerability equals weakness.

Over time, this can lead to distant or shallow relationships, and unintentionally hurtful behavior due to a lack of emotional attunement. Change becomes possible by learning to speak from emotion, recognizing the strength in vulnerability, gaining good experiences with the positive aspects of dependency and learning to overcome one’s own pride.

This subpattern can also form the basis of narcissism, as described by Hoekman, although that lies beyond the scope of this article.

- The Controlling-dismissive attachment pattern

People with this pattern avoid emotional closeness out of a deep fear of losing control—over themselves or over the situation. Emotions are seen as less relevant or even threatening, and they may struggle to name or explain what they feel. They don’t easily trust others, and interactions with them can feel tense—even if there’s no clear reason for that tension. It can feel as if you have to watch your words, without there being any obvious reason to do so. This is because the dynamic is about power, which is often linked to status or a personal domain: “I am the boss of …”

For example, if you offer them friendly advice, they might sharply respond with something like, “I know what is good for me.” This reaction shows that you have triggered something. The person adopts an exaggerated defensive attitude because they don’t want to give you power—perhaps because you ‘know better’. Yet your intention wasn’t to take control at all, but simply to help.

People with this pattern often interpret closeness as an attempt to control them, which creates problems in relationships. Their need for autonomy and control then appears to be more important than the relationship.

This defensive stance often stems from growing up with dominant or demanding parents—or in large families where constant vigilance was necessary. As adults, these individuals may prioritize autonomy over connection, which complicates relationships and can lead to loneliness.

Healing begins with learning to respond sensitively to others, allowing influence without seeing it as a power struggle, and gradually developing empathy and emotional flexibility.

Preoccupied

- The Helpless-Preoccupied Attachment Pattern

People with the helpless-preoccupied attachment pattern have an overtly negative self-image. They see others as more or better and often feel helpless without validation from others. Their statements, indecisiveness, and passive, dependent attitude make their low self-esteem very visible to those around them.

For people with this pattern, emotional stimuli can come in too strongly, overwhelming the rational part of the brain and making it difficult to process emotions clearly. As a result, they can become confused or react passively: “I don’t know what to do anymore, it must be all my fault again.”

They often feel an inner pressure to care for others, which stems from fear rather than genuine connection. By making themselves indispensable, they hope to avoid being abandoned. However, this can be experienced by others as intrusive or overbearing, leading to tension and a sense of lost autonomy. The same fear of abandonment also makes it hard for them to prioritize their own needs.

This pattern often develops when a parent does not give the child enough space to explore the world independently. Instead, the parent encourages the child—implicitly or explicitly—to adopt a helpless stance, allowing the parent to stay in control and manage their own fears or insecurities. From the outside, the parent may appear caring, but the care is not attuned to the child’s actual needs. In this way, the child’s natural fear of being left alone is reinforced.

This attachment pattern can lead to a vicious cycle of dependency, stress, and emotional exhaustion, in which the person repeatedly feels powerless and seeks constant validation from others. This cycle can be broken by learning to think more rationally in emotional situations, making independent plans, and practicing being alone.

- The Angry-Preoccupied Attachment Pattern

This subpattern is characterized by passive-aggressive behavior and the use of anger to force attention. People with this pattern often project confidence but underneath lies a deeply negative self-image. When seeking attention, they may resort to anger or erratic behavior, as this was the only way to elicit a response from a parent during childhood. They are highly sensitive to emotional cues that feel like personal injustices and tend to react disproportionately. Their behavior may come across as theatrical or intense, and they often struggle to respect others’ boundaries. Frustration is typically expressed indirectly—through sarcasm, accusations, or by deliberately breaking agreements.

This pattern may develop when a child learns that an inattentive or unpredictable parent eventually responds if the child acts out with anger or provocative behavior. In some cases, the child may also model this behavior after a parent who themselves sought attention in this way.

This pattern can lead to difficult relationships, marked by repeated attempts to force attention through conflict. It can be broken by learning to express authentic feelings more clearly and by practicing open, non-defensive communication and asking for feedback.

- The traumatic-preoccupied attachment pattern

In this subpattern, a person’s self-image is shaped by unresolved trauma from the past. For example, someone may continue to feel inferior because they received little attention during childhood—even if they are now a successful entrepreneur or artist. Stressful situations or certain emotional triggers in daily life can be linked to traumatic memories, often without an obvious cause. The trauma narrative becomes so dominant that the associated feelings can no longer be released, and the trauma becomes part of the person’s identity. Example: “My father left us when I was three, that’s why I can’t handle rejection well.” Fear of returning to the emotional pain of the trauma becomes the guiding force behind their behavior.

This pattern often arises in families where children receive little positive or sensitive feedback, where boundaries are not respected, or where neglect and emotional or physical abuse may have occurred.

This attachment pattern can lead to recurring emotional struggles, a persistent need for reassurance, and difficulty letting go of the past. It can be addressed through practices such as acceptance and interrupting negative thought patterns.

Attachment and trauma

At the end of this article, I would like to say something about attachment trauma, because it may seem as if trauma only occurs in the traumatic-preoccupied and the disorganised attachment pattern. That is not the case. Trauma can occur in all attachment patterns, but there is a difference in the extent to which the trauma has been processed or how it has been dealt with. Hoekman writes about different types of trauma that can occur in the different attachment patterns:

- The processed trauma – secure attachment pattern

- The denied trauma – dismissive attachment pattern

- Being preoccupied with personal suffering – preoccupied attachment pattern

- Complex trauma – disorganised attachment pattern

According to Hoekman, each type of trauma requires a different therapeutic approach.

Situational behavior or attachment pattern

I hope that with this article I have given you deeper insights into the dismissive and preoccupied attachment patterns. Perhaps while reading, you have already identified people around you—or even yourself—with a certain pattern. I would like to return to the distinction between attachment styles and attachment patterns. The behavior a person shows you may be situational or dependent on a specific relationship, and not necessarily reflect their dominant attachment pattern. You may recognize this in yourself: you behave quite securely attached with certain people, and suddenly quite preoccupied with others. So don’t fall into the trap of labeling someone you don’t know very well too quickly with a specific attachment pattern.

With this knowledge, however, you can start to recognize and name specific behaviors (for example, sitcoms and some series are full of derogatory-dismissive remarks), which may eventually help you see a pattern in yourself and those around you.

Finally

Unfortunately, Jeroen Hoekman’s book is not available in English, but there are other excellent English-language books about attachment. For professionals, I recommend Attachment in Psychotherapy by David J. Wallin.

Woah Sandra. Thanks for writing this but too many details to process. Bonding and attachment and relationships are so important in families and in other areas. This is so clinical and I am wary of this sterile clinical writing.

Observation is key. One of the best homework assignment in my social work somewhere workshop was go to the bus or train or airport station and watch how people meet or say goodbye.

Another creative writing homework was listen to conversations of people and write down two sentences of dialogue and use that for some writing.

In other words the book shows but does not tell. We need the stories.

Many many works of art, literature of all kinds visual work and film and entertainment tell the story of attachment and bonding. Portia in the Merchant of Venice shows how strongly she is attached to her father Shylock and her speech on mercy is amazing.

History and family history , neighborhood and all the layers along with other systems that interact with humans play a role. It’s ping pong in a way.

Klaus and Kennell two male medical doctors were deep into bonding and attachment of mothers after birth. They did some interesting work and managed to break the John Watson behavioral approach that was so prevabt from the 1920’s and beyond in the states.

Midwives had been a major player than not.

No idea how it is in your country.

Also pets and relationship to animals and nature. This has a process both internal and externally.

Thanks for all the effort and it did get me thinking. It’s a very relevant subject .

Report comment

Thank you for your comment, Mary. I completely agree—attachment and bonding are very important, not only for individuals, but also for society as a whole. I understand the article can be a lot to take in, but a good starting point is to begin distinguishing between dismissive and preoccupied behavior. From there, you can explore one subpattern at a time and consider whether you recognize it in someone you know. The derogatory-dismissive and helpless-preoccupied styles are often the easiest to begin with, as they tend to be quite noticeable.

Report comment

Here is an example of a very scholarly well-written (if a bit high level) article that would seem sensible to most people.

Yet it is based on assumptions that are extremely superficial and basically not true: “Psychological and relational issues often have their roots in childhood and are closely linked to the attachment patterns we develop early in life.”

Of course this life childhood experiences can be important in a person’s life. But it has been shown by many researchers that “psychological issues” have their roots way earlier than this life. Most students of the humanities won’t even accept this as possible because “it doesn’t make sense” to them. Yet it is so. Reincarnation is quite real and the sooner we begin to account for past life experiences in research and clinical practice, the sooner the field will begin to regain some sort of respect from the public, because it will actually provide more beneficial results.

I might add that any therapeutic approach that requires a significant degree of self-awareness will automatically filter out or reject the more difficult cases. If someone is reasonably self-aware, they will not only realize that something is wrong, but will appreciate that what they are doing has something to do with it, and will make an effort to correct themselves, if encouraged. But there are those who, while they may complain about all that is wrong, will not be willing or able to see that what they are doing is contributing to it. They don’t see any great need to change and instead call for others “who are causing my problem” to change.

Most “modern” approaches don’t work well on such cases. Such people may be more willing to take drugs than get real help. At least they can blame it on their bodies or brains, not on themselves.

This website exists because it is obvious that something needs to change in the field of “mental health care.” Particularly in the U.S. and other places that use Western “scientific” approaches rather than traditional or indigenous approaches. Some want to go back to those traditions. But they didn’t work that well, either. The direction of change needed has been pointed out at least since 1950. If people who want change aren’t even willing to look in that direction, then we are lost.

Report comment

Ms.Kouwenhoven,

Thank you for this article. I found it engaging and full of food for thought.

My family dynamic has been a challenge to clearly identify, accept and resolve. Devoting decades, evolving information, a drive to understand them & me….has caused me to grow in a remarkable way.

I have made enormous progress expanding my acceptance and compassion…..and identifying two particular ‘turning points’ that I permit myself to NOT forgive…but understand and accept now.

Ironically, so much of this occurred AFTER a false, exploitive bipolar diagnosis, the ensuing addicting polypharmacy and near-fatal side effects.

I exhibited a will and resilience that saved my life after 9 years of complex ‘sedation’, during 2+ years of withdrawal, followed by 3 years of seizures.

Being tested… and responding effectively (while still in the system & physically spiraling) changed me forever.

I have been rewarded with a dramatically improved existence; understanding & affection for myself…with compassion for my troubled, now deceased family members.

At first it seemed coincidental, unconnected, just luck. It’s not.

Heavy, worthwhile lifting.

Report comment