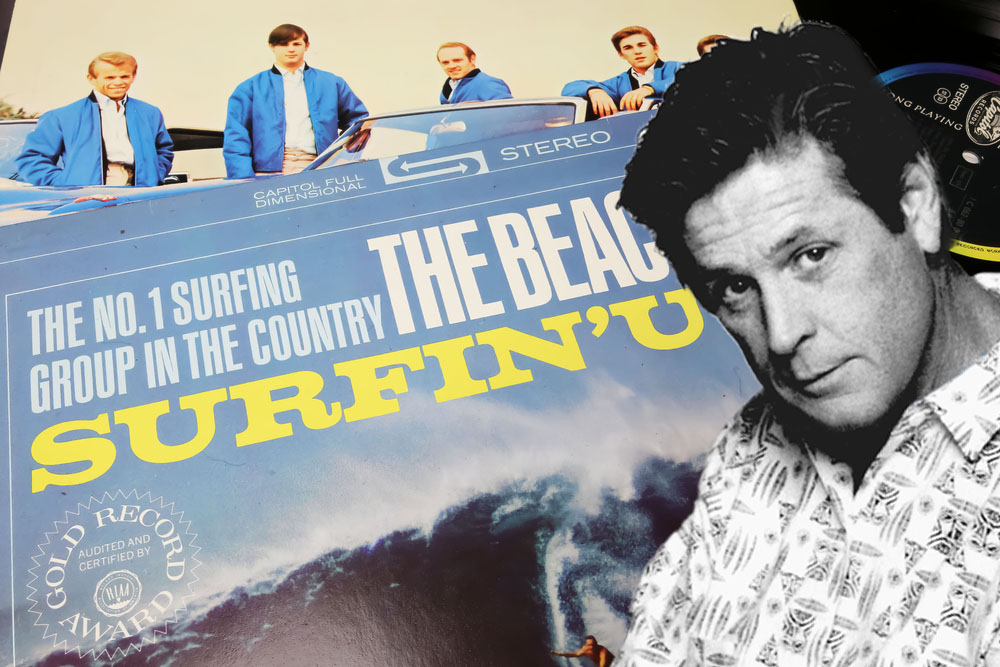

Goodbye, Brian Wilson.

One of my earliest memories of the way I approached music is when I was five years old in the living room of the apartment where I grew up. There, a piece of furniture held vinyl records. I liked the way the needle rested on the black record and how, magically in that contact, the music appeared. The first record I enjoyed listening to was Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys. I thought the cover with the young men feeding a goat was hilarious.

Ten years later I would go crazy and start my own search for meaning in the madness, until I came across the biography of Brian Wilson, leader and composer of the Beach Boys, to whom I dedicated this chapter in one of my books published in 2019. Thank you, Brian Wilson, the world is a better place because of your music.

The Landy Syndrome

The film Love and Mercy shows the drama experienced by Brian Wilson in his relationship with the psychiatrist Eugene Landy. The brilliant interpretations of the role of the psychiatrist and the role of the musician show how the process of forced mental health treatment can not only destroy a person’s life but transform him into an input for the drug industry. At the end of the film, it is reported that Landy lost his license for having psychologically subdued Wilson. Wilson finally, with the legal help of his family, regained his autonomy and with it his ability to make decisions about his own life.

I lived the experience of being subjected to psychiatry as shown in the film. After many years, I learned to call psychopharmacological treatment what it really is: a chain to the autonomy and decisions of the person. To describe these forms that mental health treatments often take, I use the neologism narco-therapy, which critically describes how psychology and psychiatry operate in concert to anesthetize, control and silence neurodivergent people like Wilson.

“Narco” refers to narcotics as anesthetizing emotions, ideas and behaviors but at the same time to the business of illicit drug use, and “therapy” refers to all kinds of therapies with anesthetic objectives, including psychiatric and psychological ones. I identified with Wilson’s character for all the years it took him to free himself from Landy’s treatments. The film opens up a series of questions about the experience of psychological and narcotherapeutic subjugation, using Wilson’s own life story as an example.

The film denaturalizes a socially naturalized problem and questions us in this sense: How is it possible to spend so much time suffering from being forced to take psychiatric drugs? Why is it not possible to simply say no? What happens to the person who is prevented from leaving psychiatric treatment?

All these questions haunted me while undergoing narcotherapy and after my release from psychiatry. Seeing the film left me with a certain sense of relief. A story that is the story of thousands of psychiatrized people had been told from the cinema. An act of justice. But the feeling I felt while watching was of having been abused and humiliated, like the musician who is subdued by the psychiatrist.

Stockholm syndrome is a psychological reaction in which the victims of an abduction develop a strong emotional bond with their captors—as in the incredible story of the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst. When psychiatric treatment begins after involuntary hospitalization, we consider it to be forced treatment. Involuntary commitment is compulsive, like kidnapping. Forced mental health treatment is coercive, like kidnapping.

The kidnapped patient experiences Stockholm syndrome with the psychiatrist who represents his or her kidnapper. Involuntary commitment and forced treatment, like kidnapping, involves depriving someone of his or her liberty. The substantial difference between kidnapping and forced treatment is that the former is illegal and the latter is legal.

All involuntary internment, like all forced treatment, implies physical violence, which is nevertheless legitimized and legalized by society. And all involuntary internment is a kidnapping, a capture, a retention against the will of that person, who at the very moment he is deprived of his freedom becomes a victim, losing all his civil rights. Now, this process is legitimized by the state, so from this perspective all forced treatment can be considered as state terrorism.

The fear that citizens suffer of being interned in an asylum turns all states in which forced treatments have been legalized and legitimized into terrorist states that have built a “chemical apartheid” for abnormal people.

This kidnapping is legitimized by civil society. Therefore, it is common to hear reactions from a relative promising “you will go to a place where you will be treated well”, or from a nurse assuring “this pill will help you to rest”, or from a psychiatrist promoting the forced treatment as “an opportunity to take a vacation from everything”. Everything that happens after the so-called “psychotic break” seems to be for the benefit of the person, but it is not.

The specificity of psychiatric abuse and the social emergence of crazy, autistic and disabled people as a political minority means that the description of the psychiatrist-patient bond needs its own term. It is a particular syndrome that has similarities with the Stockholm syndrome, but also differences that deserve to be highlighted.

I propose to call any psychiatrist-patient bond “Landy syndrome” to recall the world-famous case in which Landy was the captor, abuser and oppressor of Wilson. Unlike mental disorders, syndromes occur in the link rather than in the individual. A mental disorder is considered chronic, but a syndrome can be resolved, healed or cured when the patient frees himself from psychological dependence on his abuser.

This syndrome ends when the patient manages to free himself from oppression and begins to make decisions from his role as a “mental health service user”. The change of role from patient to user allows access to the exercise of rights that the position of psychiatric patient prevents us from exercising. For instance, it could lead the person to file complaints before the courts. To terminate this syndrome is the definitive step towards freedom, to achieve in a subversive act the “psychiatric discharge”.

It is not enough to get the mental disorder into a state of remission, but the definitive step on the road to independence from the mental health system is to get out of it. Getting “discharged” means staying within the mental health system, which means continuing to hold on to the chains. But to subvert the act of “discharge” is a matter of unsubscribing, like unsubscribing from cell phone service.

The path of madness begins in the passage of role, when one observes oneself as mentally ill, to then become a user of a mental health service and then to see oneself as a bearer of a psychiatric label in order to take a position as a survivor of psychiatry, which helps to finally become a former mental health user. The final identity step is to understand that the human essence is psychotic. In reality, we have all managed to be crazy people at some point, but we have culturally and socially constructed ourselves as sane and normal people. This final instance has nothing to do with proposing that we are all a little crazy, but that there are very few people who are actually crazy and they are the ones who have managed to stop being psychiatric patients. Julio Cortázar wrote that “Not everyone goes crazy, these things have to be deserved” and Samuel Beckett that “We are all born crazy. Some stay that way forever”. The sane society and the anti-psychotic culture educate and form us as sane people.

Looking at the past and the way in which the “psychotic break” was dealt with reveals that those moments of great suffering in which the patient may even think of taking his own life, are not so much due to the extraordinary experiences but to the desperate feeling of oppression produced by the forms of narcotherapy to which the patient has been subjected. In that discovery, it is revealed as an epiphany that the patient has survived various forms of narcotherapy. In order for this epiphany to happen, it would seem that it would be necessary to go through the horrible sensation of feeling victimized by the mental health system.

But this feeling disappears after the “survivor’s epiphany”, when it is understood that at each stage of the treatment, the patient was actually fighting for his own life, against the mental health system he was trying to chronify. All narcotherapeutic treatment of mental illness is intended to chronify the psychiatric patient, since by its very definition mental illnesses are considered by the mental health system as incurable diseases. Feeling like a victim is an extremely unpleasant feeling, because it is associated with humiliation, but this feeling disappears as soon as it is discovered that the person was not a victim, but that he/she was fighting an unequal fight, like David and Goliath.

This revelation in my case came from thinking of myself as a person who was a carrier of psychiatric labels for 22 years. One can avoid being seen as bipolar, as long as one can think of oneself as a carrier of the label of bipolarity, and the final step is rather simple, but no less important. One must give the label back to society to stop carrying that weight. I carried out this operation, which I called “giving back the label” through a performance for ten thousand people in a stadium. There I incarnated the role of David, returning the diagnosis through scenic art, in front of an audience that that day represented Goliath.

This semiological and identity path is described here in a simple and articulated way, but it is actually very complex, because when these identities start to function and circulate through the emotions and the body, a lot of imbalances are crossed that can be seen as “psychotic outbreaks” under the risk of being exposed to a new compulsive internment. There is no formula to go through this process, but it is important to emphasize that the subtle, sometimes invisible feeling of helplessness produced by being in mental health treatment is a learned feeling and should not be naturalized. It is possible to denaturalize this sensation and that the impotence becomes a power and even a libertarian act.

In short, by receiving a psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, one becomes a psychiatric patient, ceasing to be seen and treated as a “normal person”. During such treatment, one may feel victimized by a situation. If one manages to make decisions about that treatment, one can become a mental health service user. To the extent that these decisions are oriented towards social freedom and individual fulfillment, one may discover that the person actually survived psychiatry, to finally come to terms with the true nature of one’s madness.

I didn’t fight my psychiatric diagnosis for the first twenty years or so. The experience of involuntary commitment was so traumatizing and I didn’t want to repeat it. So I thought if I went along with the medication regimen I could avoid it happening to me again. Also, there was a lot of social reinforcement to go along with this as there were many movies and television episodes in the late 1980s and early 1990s that promoted the idea that one must stay on your medication or hence you would be letting everyone down.

Report comment

Chris, I experienced the same thing in the early years. I had been persuaded that I should be aware of my illness and adhere to treatment. However, I always questioned and maintained my doubts about the “scientific nature” of therapeutic treatments and the “legitimacy” of social mandates. Thank you for commenting.

Report comment

Many years ago I saw a film about the Beach Boys and Brian that changed my attitude towards their music and made me realize it was more sophisticated that it sounded.

I forget when I learned he had been pulled into the “mental health” system and fought his way back out of it. Were it that all people in the entertainment business should be so fortunate!

Report comment

Larry, what you say is true. Not everyone in show business is as lucky as Brian Wilson was. In fact, many artworks by psychiatric patients are mistakenly classified as art brut and stolen from their creators to be exhibited in psychiatric hospital museums. Thank you for commenting.

Report comment

“The fear that citizens suffer of being interned in an asylum turns all states in which forced treatments have been legalized and legitimized into terrorist states that have built a “chemical apartheid” for abnormal people.”

Well, I would say too many artists (instead of “abnormal people”) especially the visual artists, since “a picture paints a thousand words,” so a bunch of pictures about psychiatric harms, tells a damning story about the systemic crimes of both the psychological and psychiatric system (you may see a few of my pieces here, under the art section).

Marc Chagall painted the psychiatric / Spiritual war against the Jews, decades ago. And as a “Chicago Chagall,” I took a lot of inspiration from his work, and I painted the Spiritual / psychiatric and psychological crimes being committed against the American population today.

So I agree with you, “all states in which forced treatments have been legalized and legitimized [are] terrorist states.”

Report comment

Kidnapping and used for medical tests, overmedication to sedate, sure same happens in some nursing homes, absolutely terrible. The people responsible should be exposed and brought to justice. It’s against human rights. They want to kill you with lithium etc, totally not necessary just damaging your liver, alternatives could damage your heart. All of these meds have extreme side effects and are to be taken with caution especially long term… Most people get misdiagnosed anyway but once it’s done you will be stuck with this diagnosis for the rest of your life, nobody will want to listen or believe you that you are not mentally ill in the first place. Be aware and scared is all I can say. It could be you next.

Report comment

Yes, I agree that it is important to bring our stories to justice, seeking litigation to repair the damage done to us survivors of psychological and psychiatric malpractice. Thank you for commenting.

Report comment

Someone Else, I’m going to look for works by Marc Chagall, because I didn’t know he painted those motifs. And I’m also going to look for your artwork to get to know your work. Thank you very much for the references and for commenting.

[Duplicate comment]

Report comment

Someone Else, I’m going to look for works by Marc Chagall, because I didn’t know he painted those motifs. And I’m also going to look for your artwork to get to know your work. Thank you very much for the references and for commenting.

Report comment

Terrific essay, thank you, Alan!

We none of us can or do any more have “mental disorders” than we have “peripheral pain-receptors,” and for similar reasons.

Poor Sam he was mistaken

Re God, oh, and so much more;

James Joyce came so much closer:

Quote him, instead, a Stor:

“While you have a thing it can be taken from you…..but when you give it, you have given it. No robber can take it from you. It is yours then forever when you have given it. It will be yours always. That is to give.”

And:

“Every life is in many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves.”

We come here wanting only to help.

The longer we stay, the more than desire, need, desperation grows.

Thwarted, we may turn to tyrants, bullies, rapists, robbers, murderers….but ALWAYS only because what we want and need most…is ALWAYS to help!

Guy rapes a terrified woman at knifepoint…then demands to hear she enjoyed it…

Sadistic preacher has Australian convicts whipped for slacking…then ensures that at the end of each day’s toil in the baking desert heat….they tear down the wall they have built!

What makes ANY occupation or activity irksome, tedious, frustrating, agonizing….or fun?

The feeling that we are getting the biggest or the least or no or a minus bang for our buck, of course!

We cannot see the nobility in one another until we see in in ourselves. Then, like Joyce, we may see it in EVERYONE, however thwarted and subverted into “vice” and despair or desperation.

The cure, obviously, is always to restore hope of being able to recover and to help – hope, faith, love – placebos.

Yes, terrorist states, indeed…

Wishing you mirth, and with heartfelt and soul felt thanks,

Tom.

Report comment

Thanks Tomas for sahring your beautiful words… like we are searching a peaculf path.

Report comment

Now, THAT is putting it most beautifully, actually, thank you, Alan.

You appear to have brought youyrself to a point of yptoing exhaustion in responding to us all: Please know that the folloing requires no written respone!

As you may know, your first name appears to derive from the Gaelic adjective “àlainn,” meaning handsome, beautiful, fair, splendid and, by extension, noble.

And Robinson, from Son of Robin, diminutive of Robert, https://www.behindthename.com/name/robert

I don’t doubt that any middle name/s you may have are absolutely every bit as inappropriate, if scrutinized carefully enough.

It’s a bit much, a bit mad, even, to assert that

‘We none of us can or do any more have “mental disorders” than we have “peripheral pain-receptors,” and for similar reasons.,’ as I did, above, without offering any substantiation, if one wishes others to try and see it this way.

It occurred to me that, as in support of my assertion that the deepest desire, drive, destiny of each and every one of us to help as many as we can as powerfully and therefore as efficiently as we can figure out, I could cite all of literature in support of this contention.

But, on reflection, I then realized that you/I might as well throw in all art, and all of music and all of human achievement and, hey, actually all of Nature, while we are at it:

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” – John Muir.

The Universe AND more, Brother John!

But, at the risk of burning out Steve (McCrae) and bankrupting MIA/Bob, even if in a good cause, here’s some “?anecdotal evidence base” in support:

A.

Oh, YES, we have no nociceptors – no peripheral pain-receptors:

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so!”

– William Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, c 1603.

1. Alan, for sure, if you are the Zen “master” it seems you may already be (when not angry, I mean) and are capable of cracking yourself up on demand regardless of the circumstances, if you can tickle yourself to the mildest or to the most excruciating laughter, you may be one of those rare individuals in human in history to be able to demonstrate that phenomenon – possibly because more than one entity/psyche/being is using your body or, to an outside observer, you are having auditory hallucinations/passivity experiences…

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10943682/

2. Between thumb and forefinger pinch with all your might the skin of your shoulder or thigh, your unpierced, intact, healthy tongue or ear lobe: no pain.

3. Phantom limb pain occurs without the limb/digit and its cutaneous or other receptors (sensory nerve endings).

4. No fear, no pain:

Centrally-acting, pain-relieving drugs, general anesthetics such as opioids, alcohol, ether, chloroform and others induce an initial disinhibitory effect before pushing one towards coma if/as dose is increased: they all raise one’s fear threshold/s.

Certain stimulants, at least (?probably including amphetamines and xanthines such as caffeine, thephylline, theobromine…) can diminish fear/”danger responses”/’inner resistance”/”non-acceptance-of-what-already-is-in-anticipation-of-what-may-follow” by increasing our feelings of energy/strength/power/invulnerability.

5. Agents which act as local anesthetics, physically, such as ice or a thump, or chemically, such as benzocaine, cocaine, lidocaine (lignocaine) etc ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_local_anesthetics ) do not, so far as I am aware, preserve sensation while abolishing pain, but rather diminish or abolish pain by diminishing or abolishing sensation in the affected area.

6. Leap into very cold (or very hot, but not scalding) water: the initial pain soon diminishes, long before any purely physical physiological response takes (such) effects. Why? Because one’s fear subsides, “you get used to it!”

7. A trivial pain which threatens to go on growing OR to last indefinitely is far more threatening, fear-inducing, intolerable. Think mild toothache…

8. A broken bone or deep wound may cause negligible pain…until one sees it.

9. As pain wells UP following, say a really bruising kick to the buttock or testicle/s (or a winding blow to the solar plexus) up through 10-20-30-40-50-60-70-80-90-100% it can seem excruciating. But, ONCE EVER it has clearly climaxed as judged by the fact that it has JUST barely perceptibly begun to recede IN THE VERY SLIGHTEST, before cascading back down through those self-same 90-80-70% increments of sensory input, the effect is negligible, because the fear, of course, has receded so very much faster.

10. Some work of Freud, and much more, later John E. Sarno, M.D., and nowadays of Prof. Howard Schubiner and others have shown us that most chronic pain, insomnia, chronic fatigue (possibly including much “brain-fog,” I suspect), and “neurosis”/existential angst/”anxirty/depression,” along with a host of other miscellaneous conditions, among them dry-eye, frequency of urge to urinate, “idiopathic epilepsy,” tinnitus, GERD, vertigo, MEH (malignant essential hypertension), “conversion disorders” and more…are PURELY psychosomatic in origin.

This finding supports to understanding that “the reign of pain is mainly – or entirely – in the brain,” or, rather, in the mind…and the paradigm-shifting, potentially trillion-dollar saving breakthrough that the future is not so much going to be about “mind-body medicine” or the triumph of mind over matter, as that of Awareness/Understanding/Enlightenment/Psyche/Soul/Spirit over our thinking, fearing, hypervigilant minds.

Placebo?faith/hope/love/understanding is the greatest healing force available to us all, and it becomes so much more readily available when we understand that

Physical Pain = Sensation (be that sensation either real and/or imagined) + Fear

and that

Psychic/Emotional Pain = Fear (aversion, internal resistance, non-acceptance of what is already the case and of projected futures based on that non-acceptance).

B.

There may be no scientific definition of “science,” but there can be none of madness, insanity, personality illness, mental illness, personality disorder or mental disorder,” whatever about that “psychological condition” said to affect doctors and psychiatrists, “physician burn-out.”

There can be and are no “mental disorders” or “personality disorders:”

“‘Mad’ call I it, for, to define true madness,

What is ’t but to be nothing else but mad?

But let that go.”

– William Shakespere’s Polonius, c 1603.

Macbeth:

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?”

Doctor:

“Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.”

Macbeth:

“Throw physic to the dogs, I’ll none of it.”

– William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, c 1606.

Brutus.

“Cassius,

Be not deceived: if I have veil’d my look,125

I turn the trouble of my countenance

Merely upon myself. Vexed I am

Of late with passions of some difference,

Conceptions only proper to myself,

Which give some soil perhaps to my behaviors;130

But let not therefore my good friends be grieved—

Among which number, Cassius, be you one—

Nor construe any further my neglect,

Than that poor Brutus, with himself at war,

Forgets the shows of love to other men.”

– William Shakespeare’s (self-aware, “spiritually conscious”) Brutus, in “Julius Caesar,” c 1599.

Shakespeare evidently understood that absolute madness can always appear to threaten the “greatest” or “noblest” of men – such as Hamlet, Brutus or Lear – when they feel faced with appalling impossible choices, none offering a clear best outcome for all, the WIN-WIN-WIN solutions which the noblest seek, that extreme guilt (like Lady Macbeth’s), likewise, can drive anyone “out of their mind.”

Viktor Frankl of “Man’s Search for Meaning” demonstrated that, given sufficient WHY (meaning, the possibility of great service to others( we humans can withstand virtually any HOW.

Louis Zamperini (of “Unbroken,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unbroken_(film) ),

Steven Callahan (of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrift:_Seventy-six_Days_Lost_at_Sea , https://76daysadrift.com/ )

and

Diana Nyad ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhjU7VVr9io

https://www.ted.com/talks/diana_nyad_never_ever_give_up?language=en

https://www.ted.com/talks/diana_nyad_extreme_swimming_with_the_world_s_most_dangerous_jellyfish?language=en )

overcame oceans and more to live out their destinies…and to show us what presently unthinkable feats of courage, of daring and of Destiny or destinies we may not all ascend to in our own individual and collective quests to be and/or to do all we can be/do – in service of one another:

all for One and each one for All and everyone for themselves!

I predict we will take gigantic strides in doing just this when we cease seeing disorder where there is nothing but “divine,” cosmic order and always has been.

Alan, I think enumerating a dozen or so (more) points rebutting the whole unholy notion of “mental disorder” is going to be a lot more fun once I have discovered where I last mislaid the remnants of my sense of humor, and reconstructed one.

Thank YOU!

Tom.

THe human condition: Lost in thought.” – Eckhart Tolle, in “Stillness Speaks.

“All God wants of man is a peaceful heart!” ― Meister Eckhart.

“Between God and me there is no ‘between!’” ― Meister Eckhart.

“My Lord told me a joke. And seeing Him laugh has done more for me than any scripture I will ever read. ― Meister Eckhart, “Selected Writings.”

“The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me; my eye and God’s eye are one eye, one seeing, one knowing, one love.” ― Meister Eckhart, “Sermons of Meister Eckhart.”

“If the only prayer you said was thank you, that would be enough.”

― Meister Eckhart.

“Theologians may quarrel, but the mystics of the world speak the same language.”

― Meister Eckhart.

Report comment

Tom Kelly, I wholeheartedly agree!

Report comment

Coming from you, especially, Myra, this means more thank I can tell you, thank you – always assuming that you are this Myra, of course!

https://www.veteranfeministsofamerica.org/legacy/Myra%20Kovary.htm

C’mon the GIRLS, I (always! say!), c’mon the GIRLS, the WOMEN, the Valkyries, and please show us idiot men and boys that Valhalla is here and now and now and here, nowhere else!

Thank you, MYRA!

Tom.

Report comment

Yes, Tom—it’s the same Myra. Thank you for your kind words as well!

Report comment

That was the best article I’ve ever read on MIA. SPOT ON. Well said. I resonated with every word!

I feel so angry at yet so grateful for escaping not just psychiatry but the entire mental health system. I’m acutely aware I’m still at risk for involuntary treatment because every citizen is at risk for commitment as long as mental hygiene laws are on the books. But I’ll never be drugged, locked away or diagnosed into forgetting who I really am ever ever again. So grateful I “unsubscribed”

Report comment

Hi Blu, thanks for your words, and sharing. I am still so angry because I was humilliated by the terapist. But I am alive, and will try as you say, never more be involuntary treated. Mad love to yo you!

Report comment