Editor’s note: We know that our reviews of the withdrawal literature are incomplete, and we urge readers to help us add to them. Please send study citations that are relevant to the withdrawal literature for antipsychotics to [email protected].

Mechanism of Action

The class of medications described as “antipsychotics” are a heterogeneous collection of chemicals with a variety of mechanisms of action. Even within the “second generation” of antipsychotic medications, colloquially referred to as “atypical” antipsychotics, receptor-binding profiles vary widely.

The first-generation antipsychotics, also known as standard neuroleptics, block dopamine receptors, and in particular, the D2 receptor (a dopamine receptor subtype.) The second-generation antipsychotics are thought to be more broad-acting, blocking dopamine receptors and perturbing other neurotransmitter systems as well. The specific effects of each individual medication on the dopaminergic and other neurotransmitter systems vary as well.

Animal Studies

Studies on rats show some tolerance and withdrawal effects, although rats are sometimes considered a poor analogue for human neurochemistry (see Pouzet et al., 2003). Tolerance effects are compensatory changes that oppose the direct effects of a drug, e.g., a drug’s blockade of dopamine receptors induces an increase in dopamine receptors. These compensatory neurophysiological changes are thought to be a primary cause of withdrawal and rebound symptoms.

1) Csernansky, J. G., Wrona, C. T., Bardgett, M. E., Early, T. S., & Newcomer, J. W. (1993). Subcortical dopamine and serotonin turnover during acute and subchronic administration of typical and atypical neuroleptics. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 110 PubMed Link

Rats develop tolerance to second-generation antipsychotic medications.

2) Stanford, J. A., & Fowler, S. C. (1997). Subchronic effects of clozapine and haloperidol on rats’ forelimb force and duration during a press-while-licking task. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 130(3), 249-253. PubMed Link

In general, in rats, clozapine and haloperidol had similar effects, although clozapine induced high levels of tolerance in terms of time-on-task measures.

3) Stanford, J. A., & Fowler, S. C. (1997). Similarities and differences between the subchronic and withdrawal effects of clozapine and olanzapine on forelimb force steadiness. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 132(4), 408-414. PubMed Link

In rats, tolerance and withdrawal effects were observed for clozapine and not for olanzapine; these were measured by tremors in the rats.

4) Goudie, A. J., Smith, J. A., Robertson, A. & Cavanagh, C. (1999). Clozapine as a drug of dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 142(4): 369-374. PubMed Link

Rats treated with high doses of clozapine experienced withdrawal-related hyperthermia which dissipated over 4 days after discontinuation of the drug.

5) Jardemark, K. E., Liang, X., Arvanov, V., & Wang, R. Y. (2000). Subchronic treatment with either clozapine, olanzapine or haloperidol produces a hyposensitive response of the rat cortical cells to N-methyl-D-aspartate. Neuroscience, 100(1), 1-9. PubMed Link

Haloperidol, clozapine, and olanzapine were shown to exhibit tolerance effects after affecting the glutamergic system in rats. Haloperidol exhibited further effects on neurophysiology. Compensatory neurochemical responses were observed as well.

6) Goudie, A. J., Smith, J. A., & Halford, J. C. (2002). Characterization of olanzapine-induced weight gain in rats. J Psychopharmacol, 16(4), 291-296. PubMed Link

Rats given olanzapine exhibited significant weight gain within one day of treatment; after ceasing treatment rats experienced rapid weight loss.

7) Pouzet, B., Mow, T., Kreilgaard, M., & Velschow, S. (2003). Chronic treatment with antipsychotics in rats as a model for antipsychotic-induced weight gain in human. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 75(1), 133-140. PubMed Link

Humans given haloperidol do not experience weight gain, while humans given olanzapine do. However, male rats given either substance do not experience weight gain, while female rats given either substance do experience weight gain. The researchers conclude that rats are not suitable for modeling this effect.

8) Cooper, G. D., Pickavance, L. C., Wilding, J. P., Halford, J. C., & Goudie, A. J. (2005). A parametric analysis of olanzapine-induced weight gain in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 181(1), 80-89. PubMed Link

Rats given olanzapine exhibited increased eating behaviors, insulin resistance, and compensatory adiponectin levels. These compensatory changes could lead to withdrawal and rebound effects.

9) Cooper, G. D., Pickavance, L. C., Wilding, J. P., Harrold, J. A., Halford, J. C., & Goudie, A. J. (2007). Effects of olanzapine in male rats: enhanced adiposity in the absence of hyperphagia, weight gain or metabolic abnormalities. J Psychopharmacol, 21(4), 405-413. PubMed Link

Increased visceral adiposity is seen in both male and female rats when given olanzapine, despite male rats’ lack of increased weight gain. The researchers conclude that some of the neurophysiological effects of antipsychotics can still be modeled in male rats, despite their lack of obvious effects such as weight gain.

10) Goudie, A. J., Cole, J. C., & Sumnall H. R. (2007). Olanzapine withdrawal/discontinuation-induced hyperthermia in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 31(7), 1500-1503. PubMed Link

In rats, high doses of olanzapine induce hypothermia, and the discontinuation of olanzapine induces withdrawal effects of hyperthermia, which dissipate after 3-4 days. The neurophysiological reason for this is unclear.

Withdrawal Symptoms

11) Dilsaver, S. C., & Alessi, N. E. (1988). Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: Phenomenology and pathophysiology. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 77, 241-246. PubMed Link

The authors review evidence that non-dyskinetic withdrawal symptoms from antipsychotics include nausea, emesis, anorexia, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, diaphoresis, myalgia, paresthesia, anxiety, agitation, restlessness, and insomnia. The authors discuss the symptoms observed before psychotic relapse and its relation to medication withdrawal.

12) Lang, A. E. (1994). Withdrawal akathisia: Case reports and a proposed classification of chronic akathisia. Mov Disord 9(2), 188-192. PubMed Link

Description of two case reports in which withdrawal akathisia was observed.

13) Amore, M., & Zazzeri, N. (1995). Neuroleptic malignant syndrome after neuroleptic discontinuation. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 19(8), 1323-1334. PubMed Link

Although many withdrawal symptoms may be related to cholinergic rebound, rare cases of neuroleptic malignant syndrome have been observed and may be due to compensatory reactions in the dopaminergic system.

14) Schultz, S. K., Miller, D. D., Arndt, S., Ziebell, S., Gupta, S., & Andreasen, N. C. (1995). Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during antipsychotic discontinuation. Biol Psychiatry, 38(11), 713-719. PubMed Link

31% of patients with no diagnosis of tardive dyskinesia developed withdrawal-related dyskinesia after discontinuation of antipsychotic medication.

15) Anand, V. S., & Dewan, M. J. (1996). Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in a patient on risperidone undergoing dosage reduction. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 8(3), 179-182. PubMed Link

Case report of withdrawal dyskinesia as a result of risperidone dose reduction.

16) Shiovitz, T.M., Welke, T.L., Tigel, P.D., Anand, R., Hartman, R.D., Sramek, J.J., Kurtz, N.M., & Cutler, N.R. (1996). Cholinergic rebound and rapid onset psychosis following abrupt clozapine withdrawal. Schizophr Bull, 22(4), 591-595. PubMed Link

Mild withdrawal symptoms after discontinuation of clozapine are associated with cholinergic rebound and may be prevented by use of an anticholinergic medication during discontinuation. Mesolimbic supersensitivity is discussed as a potential neurophysiological cause for rapid-onset rebound psychosis.

17) Staedt, J., Stoppe, G., Hajak, G., & Ruther, E. (1996). Rebound insomnia after abrupt clozapine withdrawal. 1&) Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 246(2), 79-82. PubMed Link

Case report in which rebound insomnia was observed after discontinuation of clozapine; symptoms resolved upon re-institution of clozapine. The authors theorize GABAergic or antiglutamatergic pathways for the explanation of this symptomology.

18) Lee, J. W., & Robertson, S. (1997). Clozapine withdrawal catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a case report. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 9(3), 165-169. PubMed Link

Case report documenting “excited malignant catatonia” after abrupt clozapine withdrawal. The additional use of classical antipsychotics transformed the presentation into something “resembling” neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

19) Stanilla, J. K., de Leon, J., & Simpson, G. M. (1997). Clozapine withdrawal resulting in delirium with psychosis: a report of three cases. J Clin Psychiatry, 58(6), 252-255. PubMed Link

In these three cases, clozapine discontinuation resulted in delirium with psychosis, which the authors theorize may be due to cholinergic rebound. The authors propose slow tapering for clozapine discontinuation and/or the addition of a medication with anticholinergic effects, such as thioridazine.

20) Rowan, A. B., & Malone, R. P. (1997). Tics with risperidone withdrawal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 36(2), 162-163. PubMed Link

This case report describes Tourette-like symptoms in a child who was abruptly discontinued risperidone after 8 days of treatment, due to side effects. The psychotic symptoms that had led to the prescription of risperidone were resolved without further medication. After a second hospital admission, the child was again prescribed risperidone, which was again discontinued due to side effects; this time haloperidol was administered just after discontinuation of risperidone. Tic symptoms did not appear.

21) Rosebush, P. I., Kennedy, K., Dalton, B., & Mazurek, M. F. (1997). Protracted akathisia after risperidone withdrawal. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(3), 437-8. PubMed Link

This case report documents a patient prescribed haloperidol who developed parkinsonism and akathisia. Switching to risperidone did not resolve the side effects. Discontinuation of risperidone was associated with a severe increase in akathisia and parkinsonism symptomology. Lorazepam did not resolve these symptoms. Propranalol treatment finally resolved the akathisia symptoms.

22) Ahmed, S., Chengappa, K.N., Naidu, V.R., Baker, R.W., Parepally, H., & Schooler, N.R. (1998). Clozapine withdrawal-emergent dystonias and dyskinesias: a case series. J Clin Psychiatry, 59(9), 472-477. PubMed Link

In addition to the potential for supersensitivity psychosis, clozapine withdrawal may induce severe movement disorders. Slowly tapering clozapine discontinuation, anticholinergic medication, and resumption of antipsychotic medication may resolve these symptoms.

23) Llorca, P. M., Penault, F., Lançon, C., Dufumier, E., & Vaiva, G. (1999). The concept of supersensitivity psychosis. The particular case of clozapine. Encephale, 25(6), 638-644. PubMed Lin

Withdrawal of clozapine can induce supersensitivity psychosis.

24) Szafrański, T. & Gmurkowski, K. (1999). Clozapine withdrawal. A review. Psychiatr Pol, 33(1), 51-67. PubMed Link

Discontinuation of clozapine is associated with higher risk of relapse than discontinuation of other antipsychotic medications. The authors advise slow withdrawal, cross-titration with other medications, and caution to beware of cholinergic rebound symptoms as well.

25) Tollefson, G.D., Dellva, M.A., Mattler, C.A., Kane, J.M., Wirshing, D.A., & Kinon, B.J. (1999). Controlled, double-blind investigation of the clozapine discontinuation symptoms with conversion to either olanzapine or placebo. The Collaborative Crossover Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 19(5), 435-443. PubMed Link

Clozapine withdrawal symptoms were more likely if the patient was switched to placebo rather than to another antipsychotic (olanzapine).

26) Lore, C. (2000). Risperidone and withdrawal dyskinesia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(8), 941. PubMed Link

This case report documents a child discontinued risperidone who exhibited withdrawal dyskinesia. Symptoms resolved upon administration of quetiapine.

27) Nishimura, K., Tsuka, M., & Horikawa, N. (2001). Withdrawal-emergent rabbit syndrome during dose reduction of risperidone. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 11(4), 323–324. PubMed Link

Case report depicting rare “rabbit syndrome” resulting from dose reduction of risperidone. Trihexyphenidyl anticholinergic therapy resolved the symptoms. The authors theorize that the serotonergic system may be implicated in development of rabbit syndrome.

28) Apud, J. A., Egan, M. F., & Wyatt, R. J. (2003). Neuroleptic withdrawal in treatment-resistant patients with schizophrenia: Tardive dyskinesia is not associated with supersensitive psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 63(1-2), 151-160. PubMed Link

The authors conclude that supersensitivity of the dopaminergic system (and thus, supersensitivity psychosis) is not correlated with tardive dyskinesia, but rather follows a different mechanism.

29) Yeh, A.W., Lee, J.W., Cheng, T.C., Wen, J.K., & Chen, W.H. (2004). Clozapine withdrawal catatonia associated with cholinergic and serotonergic rebound hyperactivity: A case report. Clin Neuropharmacol, 27(5), 216-218. PubMed Link

Case report of catatonia after abrupt discontinuation of clozapine. Symptoms resolved after reinstatement of clozapine. The authors theorize serotonergic hyperactivity as well as cholinergic rebound as the cause of the withdrawal symptoms.

30) Seppälä, N., Kovio, C., & Leinonen, E. (2005). Effect of anticholinergics in preventing acute deterioration in patients undergoing abrupt clozapine withdrawal. CNS Drugs, 19(12), 1049-1055. PubMed Link

Clozapine withdrawal was associated with significant rapid deterioration in psychological health. Those taking anticholinergic medications during withdrawal were less likely to experience this deterioration.

31) Kafantaris, V., Hirsch, J., Saito, E., & Bennett, N. (2005). Treatment of withdrawal dyskinesia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(11), 1102-1103. PubMed Link

This case report depicts a patient tapered off aripiprazole and started on quetiapine who developed dyskinesia three weeks after discontinuation of aripiprazole. Treatment with a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) mixture appeared to reduce the severity of dyskinesia symptoms.

32) Komatsu, S., Kirino, E., Inoue, Y., Arai, H. (2005). Risperidone withdrawal-related respiratory dyskinesia: A case diagnosed by spirography and fibroscopy. Clin Neuropharmacol, 28(2), 90-93. PubMed Link

Case report of a patient, abruptly discontinued risperidone, who exhibited withdrawal-related tardive dyskinesia of multiple kinds, including respiratory, which is potentially lethal.

33) Michaelides, C., Thakore-James, M., & Durso, R. (2005). Reversible withdrawal dyskinesia associated with quetiapine. Mov Disord, 20(6), 769–770. PubMed Link

Case report of a patient who abruptly discontinued quetiapine and developed acute dyskinesia as a result. Reintroduction of quetiapine resolved the symptoms. Compensatory dopaminergic response to quetiapine is theorized to be the cause.

34) Mendhekar, D.N., & Duggal, H.S. (2006). Isolated oculogyric crisis on clozapine discontinuation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 18(3), 424–425. PubMed Link

Case report of abrupt discontinuation of clozapine after 6 weeks, resulting in oculogyric crisis (uprolling of eyeballs lasting for over an hour at a time) in the absence of other cholinergic rebound symptoms. It is theorized that the length of clozapine treatment was not enough to create a cholinergic supersensitivity; therefore dopaminergic supersensitivity may be implicated in the oculogyric crisis. This indicates that the dopaminergic system may be responsible for some movement disorder effects.

35) Moncrieff, J. (2006). Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 114(1), 3-13. PubMed Link

Rapid-onset psychosis, especially prevalent when withdrawing from clozapine, can occur even in patients with no psychiatric history, making it unlikely to be a relapse of a preexisting condition. Risk of relapse may also be increased by the use of antipsychotic medications.

36) Moncrieff, J. (2006). Why is it so difficult to stop psychiatric drug treatment? It may be nothing to do with the original problem. Med Hypotheses, 67(3), 517-523. PubMed Link

Withdrawal from psychiatric medications may induce somatic symptoms that can be mistaken for relapse; psychotic symptoms as a rebound syndrome, especially in the case of clozapine; psychological withdrawal symptoms that may be mistaken for relapse or may induce actual relapse; and relapse induced by the neurophysiological effects of withdrawal of the substance.

37) Oral, E.T., Altinbas, K., & Demirkiran, S. (2006). Sudden akathisia after a ziprasidone dose reduction. Am J Psychiatry, 163(3), 546. PubMed Link

Five cases of dyskinesia, abruptly appearing after dose reduction of ziprasidone, are reported.

38) Chouinard, G. & Chouinard, V. (2008). Atypical antipsychotics: CATIE study, drug-induced movement disorder and resulting iatrogenic psychiatric-like symptoms, supersensitivity rebound psychosis and withdrawal discontinuation syndromes. Psychother Psychosom, 77, 69-77. PubMed Link

The authors argue that the lack of efficacy of risperidone and quetiapine when compared with olanzapine (as demonstrated in the CATIE study) could be due to supersensitivity psychosis rather than simple lack of efficacy. The authors note that approximately half of all patients given antipsychotics (combining both “classical” and “atypical”) experience movement disorders including parkinsonism, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia. These movement disorders are associated with high levels of psychiatric symptoms as well, including “suicidal and depressive symptoms” (p. 72). Additionally, these movement disorders produce symptoms which can be mistaken for both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, thus leading to misdiagnosis and mistreatment (see also Margolese, Chouinard, Walters-Larach, & Beauclair, 2001).

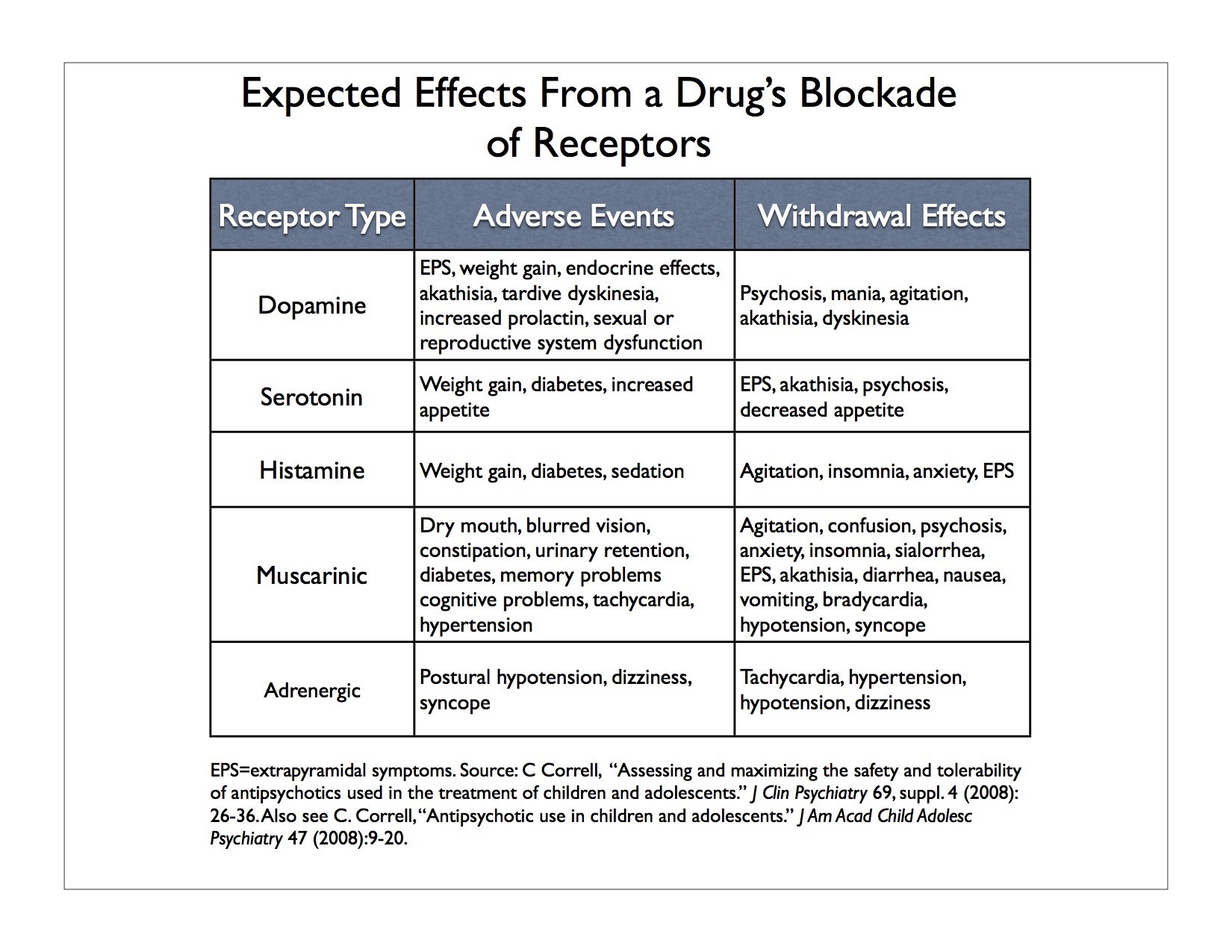

39) Correll, C. U. (2008). Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: Minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 47(1), 9-20. Also see, Correll, C. U. (2008). Assessing and maximizing the safety and tolerability of antipsychotics used in the treatment of children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry, 69(suppl 4), 26-36.

In these two articles, Correll lists numerous rebound/withdrawal symptoms and the neurochemical systems implicated in them. Correll links drugs acting on the D₂ system to withdrawal psychosis, mania, agitation, akathisia, and withdrawal dyskinesia. He links 5-HT₁A partial agonist drugs to EPS/akathisia. Drugs acting on 5-HT₂A are associated with EPS/akathisa and psychosis. Action on 5-HT₂C is linked to decreased appetite. α₁ is linked to tachychardia and hypertension; α₂ is linked to hypotension and dizziness. H₁ is associated with agitation, insomnia, anxiety, EPS. M₁ (central) is associated with agitation, confusion, psychosis, anxiety, insomnia, sialorrhea, EPS/akathisia. M₂-₄ (peripheral) is linked to diarrhea, diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, hypotension, and syncope.

40) Ahmad, M.T., & Prakash, K.M. (2010). Reversible hyperkinetic movement disorder associated with quetiapine withdrawal. Mov Disord, 25(9), 1308–1309. PubMed Link

Case report. Two days after discontinuing quetiapine abruptly, patient developed a complex hyperkinetic movement disorder. Reinstitution of quetiapine resolved the symptoms. Withdrawal effects may have been caused by compensatory up-regulation of the dopaminergic or serotonergic systems.

41) Ozcan, S., Soydan, A., & Tamam, L. (2012). Supersensitivity psychosis in a case with clozapine tolerance. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 16(4 Suppl), 70-73. PubMed Link

Patients develop a tolerance to clozapine, and thus develop dopamine supersensitivity, which increases the likelihood of psychotic symptom relapse even while remaining medication compliant.

Numerous withdrawal symptoms have been reported with both classical and second-generation antipsychotics, and fit into several categories. Physical withdrawal symptoms may occur; rebound psychosis is found especially in discontinuation of clozapine; other rebound syndromes have been observed; and psychological withdrawal symptoms are possible as well.

42) Wadekar, M., & Syed, S. (2010). Clozapine-withdrawal catatonia. Psychosomatics, 51(4), 355. PubMed Link

In this case report, abrupt discontinuation of clozapine led to catatonia and autonomic instability, which resolved upon re-initiation of clozapine treatment.

43) Sansone, R. A., & Sawyer, R. J. (2013). Aripiprazole withdrawal: A case report. Innov Clin Neurosci, 10(5-6), 10-12. PubMed Link

In this case report, a patient experienced withdrawal symptoms after abruptly discontinuing aripiprazole. The researchers theorize the symptoms may be due to serotonergic causes.

44) Cerovecki, A., Musil, R., Klimke, A., Seemüller, F., Haen, E., Schennach, R., … Riedel, M. (2013). Withdrawal symptoms and rebound symptoms associated with switching and discontinuing atypical antipsychotics: Theoretical background and practical recommendations. CNS Drugs, 27, 545-572. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0079-5 PubMed Link

Second generation antipsychotics affect a number of receptor systems within the brain. All serve to block dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, while some have additional effects on other dopamine and serotonin receptors, as well as the histaminergic, muscarinergic, and adrenergic receptor systems. Medications that act on the histaminergic receptors may moderate weight gain. Medications that block the M1 muscarinergic receptors may help treat EPMS in schizophrenic patients, but the authors note the propensity for side effects such as reduced cognitive function, dry mouth, tachycardia, obstipation, and urinary retention. Medications that block the α2 adrenergic system are used to prevent male sexual dysfunction, improve mood, and may increase cognitive function. Because of these effects, withdrawal and rebound symptoms may involve any of these systems.

The authors link early dyskinesia to an increase in dopamine caused by the body’s attempt to self-regulate dopamine levels after receptor blockage by medication; they link late dyskinesia to hypersensitivity of certain dopamine receptors. They link parkinsonism to a reduction in striatal dopamine. The authors state that the chemical mechanism causing akathisia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome are unknown, though they present a theory that a nearly full blockage of D2 receptors may be responsible for the latter.

The authors warn of withdrawal dyskinesia, rebound parkinsonism, and rebound akathisia after abrupt discontinuation of D2 receptor antagonists. Like tardive dyskinesia, supersensitivity psychosis might be due to an increase in dopamine receptor sensitivity after a medication blocks receptors. For clozapine and quetiapine in particular, as well as olanzapine, there is evidence for the danger of supersensitivity psychosis and dystonias and dyskinesias after withdrawal.

Rebound psychosis can be differentiated from reemergence of an underlying psychosis in several ways: symptoms should resolve faster if the medication is restarted in rebound psychosis; and other withdrawal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, insomnia, diarrhea, agitation, headache, and sweating (cholinergic rebound symptoms) may accompany rebound psychosis.

The authors say it is unknown what mechanism is responsible for rebound-induced hyperthermia (associated with the discontinuation of olanzapine), but that serotonin receptors may be involved.

Withdrawal from a substance with anticholinergic properties such as clozapine and olanzapine may result in cholinergic rebound (nausea, vomiting, sweating, sleeping problems, flu-like symptoms, and psychosis). The psychotic symptoms are indistinguishable from dopaminergic withdrawal symptoms of psychosis.

After discontinuing an antipsychotic with adrenergic effects, rebound symptoms may include an increase in blood pressure and fear.

45) Alblowi, M. A., & Alosaimi, F. D. (2015). Tardive dyskinesia occurring in a young woman after withdrawal of an atypical antipsychotic drug. Neurosciences (Riyadh), 20(4), 376-379. PubMed Link

Case report of a patient experiencing 9 months of withdrawal dyskinesia after discontinuation of risperidone. Symptoms resolved after administration of amantadine.

46) Li, M. (2016). Antipsychotic-induced sensitization and tolerance: Behavioral characteristics, developmental impacts, and neurobiological mechanisms. J Psychopharmacol , 30(8), 749-770. PubMed Link

The author provides a thorough review of neurophysiological sensitization and tolerance effects to antipsychotic medications, which has implications for withdrawal effects.

Switching antipsychotic medications as a withdrawal strategy.

Switching antipsychotic medications may reduce the possibility of withdrawal effects if done with careful consideration to the neurophysiological properties of each medication. However, withdrawal effects are still possible.

47) Correll, C. U. (2006). Real life switching strategies with second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry, 67,160-161.

Abrupt switching between medications is far more likely to cause withdrawal and rebound effects. However, slow cross-titration may increase the likelihood of side effects and may maintain side effects from the first medication, and may be confusing for the client. Correll recommends an individualized strategy. Correll cautions that although previous research shows no difference in effectiveness between various switching strategy, those studies were industry-sponsored and have methodological problems.

48) Correll, C. U. (2008). Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: Minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 47(1), 9-20; Correll, C. U. (2008). Assessing and maximizing the safety and tolerability of antipsychotics used in the treatment of children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry, 69(suppl 4), 26-36.

Correll recommends slow cross-tapering when switching medications. Correll urges caution when switching from a medication that affects the histaminergic and muscarinergic systems to a medication that has less effect on these symptoms.

49) Cerovecki, A., Musil, R., Klimke, A., Seemüller, F., Haen, E., Schennach, R., … Riedel, M. (2013). Withdrawal symptoms and rebound symptoms associated with switching and discontinuing atypical antipsychotics: Theoretical background and practical recommendations. CNS Drugs, 27, 545-572. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0079-5 PubMed Link

The findings here are hampered by lack of specific switching trials for many of the medications listed here. When studies of switching do exist, they are likely industry funded and do not discuss the possibility of adverse effects as rebound or withdrawal symptoms.

The evidence for the efficacy of switching antipsychotics is limited. An analysis of the CATIE study showed that switching to a new antipsychotic does not improve outcome compared with those who remained on current medication. Additionally, switching makes patients more likely to stop taking their medication altogether.

The authors recommend plateau cross-titrated switching strategies in almost all cases, although they state that for drugs with a longer half-life, more abrupt switching is less problematic. However, they note that increased risk of adverse events occurs when the patient is taking two or more antipsychotic medications simultaneously, as one would during plateau cross-titration.

Switching from a medication that blocks D2 receptors to one that blocks less or activates D2 receptors may result in normalization of prolactin levels and resolution of sexual dysfunction.

Switching from a second generation AP with high 5-HT2A receptor affinity to a first generation AP may result in the resumption of negative and cognitive symptoms and development of EPMS.

Switching treatment from clozapine or olanzapine (blocking 5-HT2C receptors) to risperidone, aripiprazole, or ziprasidone may result in resolution of weight gain problems. This may also result in decreased sedation and less likelihood of rebound insomnia.

50) Margolese, H. C., Chouinard, G., Kolivakis, T. T., Beauclair, L., Miller, R, & Annable, L. (2005). Tardive dyskinesia in the era of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Part 2: Incidence and management strategies in patients with schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(11), 703-714. PubMed Link

In cases in which TD is an adverse effect from use of classical antipsychotics, the authors recommend discontinuation of classical antipsychotic treatment, but substituting them with second-generation antipsychotics to reduce the risk of withdrawal-onset TD.

Tapering Success Rates

51) Cohen D. (2007). Helping individuals withdraw from psychiatric drugs. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 21(3-4), 199–224. ResearchGate Link

This article offers advice to mental health professionals regarding strategies for discontinuation of psychiatric drugs. The author notes that there is a dearth of evidence regarding success rates and best tapering practices, but advises slow tapering off the medications in general.

Consumer Accounts of Discontinuation

Consumers generally experience poor communication and low levels of support from their mental health service providers around the experience of discontinuation. This leads to poorly-conducted discontinuation attempts, which involve severe withdrawal symptoms. Thus, many consumers return to the medication, believing that discontinuation is not possible or that it results in a resurgence of their disorder.

52) Roe, D., Goldblatt, H., Baloush-Klienman, V., Swarbrick, M., & Davidson, L. (2009). Why and how people decide to stop taking prescribed psychiatric medication: Exploring the subjective process of choice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 33(1), 38–46. doi:10.2975/33.1.2009.38.46 PubMed Link

Patients decided to discontinue their medications for a number of reasons, including feeling loss of things previously cared about (i.e. inability to concentrate, sexual side effects, lack of connection to important parts of self), condescension and lack of care from healthcare agents, alienation of being a medication-taker, and feeling that the fear-based pressure to take medications was not a valid reason to be continuing them.

53) Salomon, C., & Hamilton, B. (2013). ‘All roads lead to medication?’ Qualitative responses from an Australian first-person survey of antipsychotic discontinuation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36(3), 160-165. PubMed Link

Participants report not receiving much information about discontinuation, feeling unheard by their treatment provider around discontinuation, and experiencing significant withdrawal symptoms during discontinuation. Unsupported discontinuation led to many negative effects for the participants, leading most of them to eventually resume taking antipsychotic medications.

51) Salomon, C., Hamilton, B., & Elsom, S. (2014). Experiencing antipsychotic discontinuation: Results from a survey of Australian consumers. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21, 917-923. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12178 PubMed Link

Consumers often discontinue antipsychotic medications without the knowledge of their clinician. Almost half of the consumers in the study reported that their doctors did not communicate regarding how long they would need to be on the medication. Of those that did communicate, almost ¾ stated that the patient would need to be on the medication indefinitely or for life. Over half the consumers in the study stated that they were not informed about potential withdrawal effects. More than half the consumers in the study stopped their medications without their doctors’ knowledge, usually because of adverse effects from the medication. More than ¾ of the participants reported withdrawal symptoms after discontinuing their medication. Withdrawal effects included insomnia, mood change, anxiety, agitation, psychotic symptom increase, difficulty concentrating, paranoia, headaches, memory loss, nightmares, nausea, and vomiting.

Additional References

Lieberman, J. A., Stroup, T. S., McEvoy, J. P., Swartz, M. S., Rosenheck, R. A., Perkins, D. O., . . . Hsiao, J. K. (2005). Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353(12), 1209-23. PubMed Link

“The majority of patients in each group discontinued their assigned treatment owing to inefficacy or intolerable side effects or for other reasons. Olanzapine was the most effective in terms of the rates of discontinuation, and the efficacy of the conventional antipsychotic agent perphenazine appeared similar to that of quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Olanzapine was associated with greater weight gain and increases in measures of glucose and lipid metabolism.” (p. 1209).

Margolese, H. C., Chouinard, G., Walters-Larach, V., Beauclair, L. (2001). Relationship between antipsychotic-induced akathisia and tardive dyskinesia and suicidality in schizophrenia: Impact of clozapine and olanzapine. Acta Psychiatr Belg, 101, 128-144. ResearchGate Link

Duxbury, J., Wright, K., Bradley, D., & Barnes, P. (2010). Administration of medication in the acute mental health ward: Perspective of nurses and patients. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19(1), 53-61. PubMed Link

Patient reports involve general support for medication, but a desire for more communication between providers and patients, as well as more support in dealing with side effects of medication.