The medical model of diagnosis has become a dominant idea in the field of mental health, but it hasn’t always been this way. As a therapist, I will explore whether mental health diagnosis is a useful way of thinking about human suffering.

When are psychological diagnoses used?

- For reimbursement for third-party payers.

- Mental health professionals communicating with colleagues.

- Mental health professionals communicating with clients

In the first use, insurance companies and government agencies use diagnoses because they want to ensure that people only receive a treatment if they need it and that they are being given the most appropriate treatment for their problems.

In the second use, mental health professionals are trying to convey the most pertinent information about their clients and give their colleagues the highest quality understanding of a client’s situation.

In the third use, mental health professionals are trying to help clients understand what they are experiencing and why.

The natural question that arises here is whether the medical model of diagnosis is the best way to accomplish those aims. In order to address this question we will explore:

- Are “mental illnesses” real?

- Is thinking in terms of “mental illness” and diagnosis helpful to clients?

Defining the Medical Model

There are many ways to define the medical model of diagnosis. I will offer two. First, Gerald Klerman was highly involved in the creation of the DSM-III and was the highest ranking psychiatrist in the US government at the time. Just before the DSM-III was approved by the APA, Klerman published the following:

- Psychiatry is a branch of medicine.

- Psychiatry should utilize modern scientific methodologies and base its practice on scientific knowledge.

- Psychiatry treats people who are sick and who require treatment.

- There is a boundary between the normal and the sick.

- There are discrete mental illnesses. They are not myths, and there are many of them.

- The focus of psychiatric physicians should be on the biological aspects of illness.

- There should be an explicit and intentional concern with diagnosis and classification.

- Diagnostic criteria should be codified, and a legitimate and valued area of research should be to validate them.

- Statistical techniques should be used to improve reliability and validity.

(Klerman, 1978)

I would distill this perspective down to two main tenants:

- There is such thing as “true mental illness” or “chemical imbalance” in which psychological symptoms cannot be understood in terms of the person’s psychology.

- “Mental illness” can be divided up into a finite number of discrete diseases, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression.

The Optimist and the Weirdo

In order to properly understand where this way of thinking came from, we can look to the two men that have been most influential in creating and advocating this model.

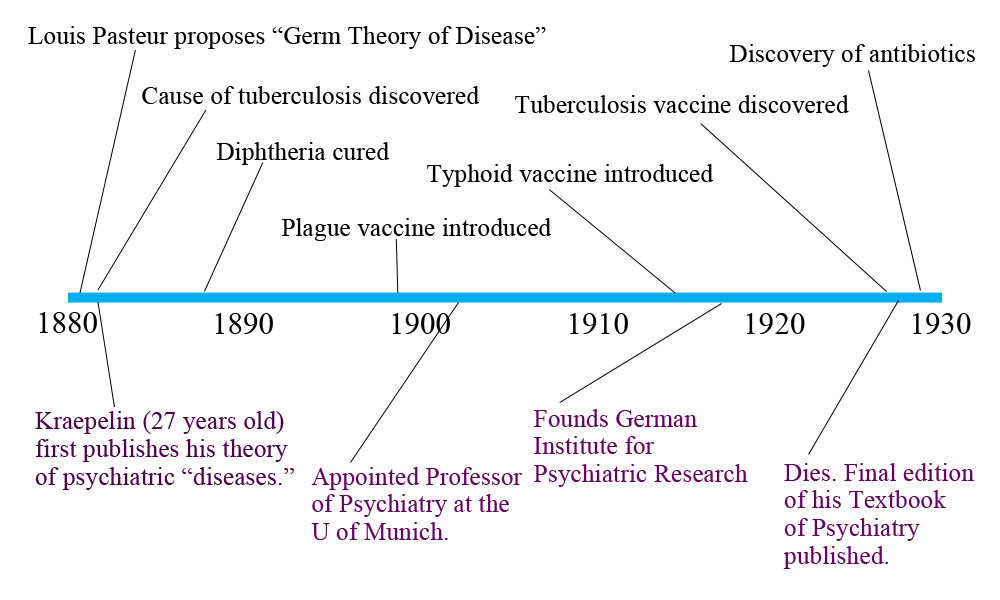

Emil Kraepelin can be thought of as an optimist. He was a German psychiatrist, a contemporary of Freud, who first proposed the idea of “psychological diseases.” In order to understand where this idea came from, we need to look at what was happening in medicine at the time. Kraepelin first published his theory just after Louis Pasteur proposed the Germ Theory of Disease. During Kraepelin’s career, he saw the shift in medicine from thinking in terms of imbalances and humours to thinking in terms of germs and diseases. He saw this shift in thinking lead to enormous advances in helping people.

As you can see, Kraepelin saw the field of medicine discover the causes of major diseases and develop cures and vaccines. He hoped that the disease model, if applied to psychiatry, could could lead to similar advances. So he set out to try to discover psychiatric diseases. Since every real disease shares common symptoms, etiology (cause), and response to treatment, he believed that if he could correctly group symptoms, they would also share an etiology and response to treatment.

A Real Psychiatric Disease

In order to clarify what Kraepelin meant by mental disease, it can be helpful to look at a condition that actually meets those criteria. Wilson’s Disease is caused by mutations in the Wilson’s Disease Protein Gene (ATP7B) which causes copper accumulation. It has a single cause. Wilson’s Disease causes depression, anxiety and psychosis in addition to tremors and jaundice due to liver and nervous system damage. It has a recognizable cluster of symptoms. Removing copper from the system (through chelation) prevents further damage. Everyone with Wilson’s Disease responds in a predictable way to treatment.

Schizophrenia, Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorder are examples of so-called diseases that do not even come close to meeting Kraepelin’s criteria. After 100 years of grouping and regrouping symptoms, psychiatry has found extremely few diseases with symptoms, etiology and response to treatment that properly cohere. Certainly this way of thinking has not led to the kind of advances Kraepelin had hoped for. If Kraepelin were alive, I believe he would advise us to look for another paradigm.

Robert Spitzer was a Real Weirdo

Robert Spitzer was the creator of the DSM-III and chiefly responsible for taking Kraepelin’s ideas from relative obscurity to being the dominant paradigm in the mental health field. The adoption of DSM-III in 1980 was the most decisive move in the history of mental health away from thinking in terms of personal experience and the uniqueness of the individual in his social context, and toward the medical model.

Spitzer’s influence on the field was enormous. DSM-I and DSM-II both represented the view of psychological problems as being expressions of inner-conflict and difficult life experiences that were only able to be properly understood by understanding the individual or family. Spitzer’s DSM-III was the decisive break to a view of psychological problems as being best understood as specific disorders. There is no longer a need to understand the context.

Why was the mental health field willing to listen to Spitzer? In the 1970’s there was a crisis in psychiatry and the field was looking for a new paradigm. There was a broad antipsychiatry sentiment in academia and popular culture from Thomas Szasz and Michel Foucault to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Third-party payers were demanding that psychiatry demonstrate the efficacy of their practices as they wanted to be paid to treat people with increasingly mild distress. There was pressure from the emerging field of psycho-pharmaceuticals to be able to market their drugs for specific diseases and newly deinstitutionalized patients. Conflicts between various theoretical camps, and those who viewed psychological theories as too subjective were destabilizing. And psychiatrists were feeling threatened by other professionals delivering psychotherapy (Resnick vs. Blue Shields, 1980 was a court case that prohibited Blue Shields from requiring psychologists be supervised by an MD in order to provide therapy).

Psychiatry was obviously facing huge problems and it makes sense they were looking for a savior to save them. They chose Robert Spitzer.

In a 2003 interview with NPR, Spitzer described himself as someone who is much more interested in fitting puzzle pieces into a system than he is in understanding human emotion. In fact, he said that he did not view himself as having a particularly good understanding of people. As a 12 year-old boy, he would graph his attractions toward 5 or 6 girls at his summer camp. After retiring from psychiatry, he proceeded to develop a complicated categorical system for ballroom dancing. However, the ballroom dancing community has been less willing to adopt Spitzer’s categories than has mental health field.

When Spitzer began developing the DSM-III in 1974, diagnosis was an unpopular specialty. He was able to appoint himself to head all 25 committees. The development of the manual was not based on any research. Former Columbia Professor David Shaffer (who worked with Spitzer on the DSM-III) described the process as one in which a group of psychiatrists met in a small room and argued with each other loudly. He said that the loudest person would be the one whose view prevailed. In these discussions, they concluded it would be “ludicrous” to call racism a disorder, but that PMS was. Spitzer was in favor of keeping homosexuality a disorder but backed down after fierce protest. In other words, these categories were based on a small group’s subjective opinions rather than discovering actual diseases with symptoms, etiology and treatment response that properly cohere.

Why Did the Rest of the Field Follow Psychiatry in Adopting the DSM-III?

It is clear that psychiatry was looking for a new paradigm to reestablish their position atop the mental health field. But why did other professions follow? For starters, the most influential mental health professionals in government and private insurance were psychiatrists. This led to private insurance companies and government agencies becoming much stricter about requiring diagnosis after DSM-III. There was also a growing shift from out-of-pocket payment for therapy to an increasing reliance on third-party payers.

So Is Diagnosis Helpful?

While a fair amount of research has been put into trying to prove the DSM’s diagnoses are reliable, there has not been a single study aimed at testing whether using diagnoses increases therapeutic outcome. However, all evidence shows that mental health treatment as a whole has not improved since diagnosis has become ubiquitous. Clearly, Kraepelin’s hopes have not come true.

If Not Disease, Then What?

Returning to the three main reasons mental health professionals use diagnoses: (reimbursement, communicating with colleagues, communicating with patients), we can think of other paradigms that might be more effective at accomplishing these aims.

Other possible paradigms include symptom-oriented descriptions (listing client symptoms and severity without trying to group them into a disorder) and complaint-oriented descriptions (describing the client’s own reasons for seeking treatment). Consider the following:

I believe that we can better accomplish these aims without using the medical model of diagnosis. I do not believe there is any reason to believe that the diagnoses listed in the DSM are “real disorders” in the sense that both Kraepelin and Klerman hoped they would be.

What are your thoughts about the medical model of diagnosis vs symptom-oriented or complaint-oriented approaches?

This article is FANTASTIC!! Thank you for your accurate historical analysis and very pertinent question.

To answer it: I fully agree that we can throw the DSM out the window and probably be much better for it. I would love to live in a world without the DSM, characterized instead by compassion for human suffering (subjectively and individually defined) and real support to humans in distress — and out of it, too!

Report comment

This is an excellent short summary of a long century of error, which hopefully is coming to an end. For great detail about this history, I highly recommend a recent book, American Madness: The Rise and Fall of Dementia Praecox, by Richard Noll (2011, Harvard University Press).

I think you’re quite right to suggest that Emil Kraepelin himself, given the full perspective of today’s accumulated experience, would reject the medical model outright.

Report comment

The medical model of diagnosis is wishful-thinking on the part of psychiatrists and service providers. Wouldn’t it be nice if one could neatly classify human emotions as specific diseases and have a little pill to cure each one. It certainly would make life easier for psychiatrists but, shucks! human nature and life in general refuse to fit neatly in little boxes. I would say: get realistic and stop dreaming!

Report comment

One fundamental problem with diagnosis on the basis of “symptoms”, I’ve found, is that this only describes the way a person’s problems appear on the surface, especially to others. It doesn’t explain the inner dynamics contributing to the apparent dysfunction. So the person gets told their “problem” is what is visible, when in fact the real issues could be much deeper. For example, telling someone they have a mood disorder may not help at all, when the issues are stemming from identity, belonging and self-esteem. They will end up spending time trying to control “the moods”, and avoid the deeper issues. I’ve found it makes more sense to think of myself as an individual with a story than to try to think in terms of “symptoms”.

Report comment

It’s a good article. I didn’t know Mr. Kraeplin was 27 when he came up with this crap. Makes me hate him more. Some young whipper snapper setting the seed for the destruction of millions of lives, or at least playing a large part in it.

Fake doctors don’t get to use the word ‘symptom’ around me and be taken seriously. It’s my new rule. But complaint oriented help, I see no problem with. What you need to remember is that often it is not the person complaining to the psychiatrist, but the person who wants the psychiatrist to strip away somebody else’s freedom and human rights who is doing the complaining.

It’s a steaming pile of pseudoscience, and I would personally be ashamed of myself if I’d trained as one. The ones with a history of human rights abuses need to be put in prison, and that’s a lot of them.

Report comment

I definitely think psychiatric diagnosis need to be reframed as a unique area of medicine that is not comparable to diagnosis like cancer or diabetes. But I think we are too entrenched in the medical model to give it up completely.

You left out a couple important way psychological disorders are used

– In the courts, to determine whether someone is mentally capable to stand trail or if their culpability for a crime is reduced because of mental disorder

– For children receiving special education services in school

-Determining rights under ADA

In short, all the ways our government tries, for better or for worse, to create a level playing field for people with mental disorders. If we revert to calling them symptoms, then what would be the process for providing equal protection under law? One school might allow accommodations for children who show the symptom of being easily distracted, another might not. One employer might discriminate in hiring, another might not. One judge might think a person under psychosis is fully liable for their actions, another might not. How we handle these issues now is far from perfect, and psychiatrists and the DSM have too much power in the system, but I think the medical model needs to be reformed instead of done away with.

Report comment

It doesn’t matter what the intentions of a judge are, to punish or be ‘therapeutic’, being sent to psychiatry after a crime is a fate worse than prison.

Even the Norway shooter called it a “fate worse than death” this week in the press. He knows what he faces, a cushy Norway prison, or the living hell of being turned into one of the millions of human bodies who are owned by psychiatry lock, stock and barrel that psychiatry can do whatever they wish to, regardless of how the former owner of that body feels about it.

It makes me want to throw up just thinking about how horrible it would be to be a criminal who is sentenced to psychiatry rather than prison. It’s horrific.

Report comment

As I said, the relationship between psychiatry and law is far from perfect. I have very mixed feelings about the insanity defense, and i’m against forced treatment. However, as a matter of justice, there seems to be a difference between someone who commits a crime intentionally, and someone who commits a crime when s/he was not fully aware of the circumstances or potential outcomes of their actions. And Norway prisons are nothing like US prisons.

Report comment

“However, as a matter of justice, there seems to be a difference between someone who commits a crime intentionally, and someone who commits a crime when s/he was not fully aware of the circumstances or potential outcomes of their actions.”

If someone has shown themselves to be dangerous you have to lock them up. Why does society insist on torturing them with psychiatry, when many would prefer prison? Why isn’t the person at least given the choice? Trust me, even if you think sending a criminal to psychiatry isn’t a ‘punishment’, it is.

Report comment

As long as we need insurance to fund access to mental health professionals (including psychiatrists, counselors and therapists)the requirement for diagnoses, and thus labeling, will continue. We forget that business, not patient needs, drive the medical profession (e.g., the 12 minutes pcp’s spend with patients in order to be cost-effective). Let’s not leave out most doctors and hospitals from this description, either.

More to the sociological point, mental disorders continue to carry a stigma, maybe even more so in a society that values and seeks “perfection”. I am always surprised at how long my 20-something clients wait before seeking counsel; fearing what others (even themselves!) will think. Of course, there are people with mental health disorders we ought to avoid, like sociopaths or paranoid schizophrenics, but many of us – 15-17 million Americans, more than AIDS, cancer, or heart disease according to the NIMH — encounter depression each year. Depression benefits from medical intervention as much as cancer benefits from psychotherapy. I believe that most everything that happens to us human beings is a biopsychosocial event, inextricably intertwined with all that we are. Optimizing who we are, treating ourselves well, calls for us to seek out many interventions as a natural part of the human experience. It’s too bad we’ve allowed some of those interventions to be such hot potatoes.

Report comment

“Diagnoses” are just descriptions of what we find uncomfortable or puzzling or difficult to manage. The DSM IV itself clearly states that “there is no assumption that people having the same diagnoses are similar in all important ways.” In other words, two people with the same diagnosis may have different things wrong with them and require different approaches to help them. Well what’s the point of having a diagnosis that doesn’t identify the actual problem or direct an effective treatment? Answer: there is no point.

I only ever used psych diagnoses when I had to in order to get the person’s service paid for. I chose the diagnosis that would be most likely to get the person the service they needed. If I had to explain the diagnosis to my client, I’d explain that the insurance company needed me to put down some numbers so they’d be willing to pay, but that I put little stock in their “diagnosis” because I knew their situation was unique and could not be described by a code number. I sometimes even read them the criteria and asked them if they thought it fit their situation. There was never any reason for me to use the diagnosis as part of therapy. It was an annoyance and a distraction at best.

—- Steve

Report comment

Sounds good.

Report comment

And using bogus diagnosis as a way to get paid is a crime against the so called patient that will haunt him or her for the rest of his/her life. This is total fraud and violation of human rights no matter how nicely you try to describe it.

Many in the mental “health” profession learn to profess lies by updiagnosing to get maximum insurance payments from the victims’ health insurance. Bipolar fraud was committed in outrageous numbers as a misdiagnosis for PTSD and other distress since PTSD didn’t provide lavish lifelong benefits for lethal drugs to destroy countless lives with the pretense bipolar was biological and PTSD was not.

The DSM is total fraud junk science that destroys countless lives for an increasingly fascist global “new world order” to make slaves of humanity for the psyhchopathic power elite. See Dr. Paula Caplan’s THEY SAY YOU’RE CRAZY and her web site on the huge harm caused by psych diagnoses she is protesting with victims now.

Thre is no justification for these bogus, life destroying stimas whatsoever!

Report comment

I went to Group Therapy 3-4 years ending in 1978. I was cured of lifelong emotional repression and dysfunctional condition.

Only much later, 25 years later did I think or realize “Oh yeah, that is what they now make so much hoopla about and label as ‘schizophrenia'”. Oh yes, I had taken meds which I now know were anti-psychotic SZ meds and had seen the word Schizophrenia on the social assistance forms but soemhow, incredibly, it had meant nothing to me -no more than the words, ‘depressed’, ‘anxiety’ or ‘blunted aspect’ etc – I didn’t care- I was only concerned with my real world inside that I was battling with and always , yes always wanted to fix.

I didn fix it. I did not ‘get better’, I did not learn to be obedient and behave to someone else’s standard – I fundamentally changed my metabolism , my emotional functioning – primarily through energetics and confrontational therapy.

Interestingly , as I look around 35 years later to find the practices that I know cured schizophrenia, they are very hard to find. Most of the psychotherapists are doing thing tan simply cannot cure sever problems and worse than that they abhor doing the things that would cure.

…

Facilitating patients to be angry! Holy boom Bats! Sounds like communism! what’s next? Freeing them from the plantations? Letting them go off their meds?

…..

….

Miraculously , somehow I had escaped indoctrination, I din’t know I was a label and I didn’t know I had an incurable brain disease.

Lucky old me. It couldn’t happen today.

…

At the time I thought I must be ‘one of a few’, but for the next twenty five years I never met another like myself. I never thought about it, my only concern was to blend in and hide my past.

In 1985, I started a corporate career. In the first week I passed by and walked in on an Anti-psychiatry conference. I thought: I want to get up and tell them my story – then I realized that would be career suicide , so I walked out. I know other people like myself through the internet now – they too have built new lives and they refuse to destroy them by going public.

We are here, we walk among you, you would never guess what we once were, but this society is far to dangerous to come out for those that need to integrate with the mainstream. The APA and the multi-billion dollar pharmaceutical industry not only does not cure anyone, it treats cured people as enemies and creates an environment which is hostile to the healed and the cured.

The APA’s business is to diagnose in order to administer chemical lobotomies to socially problematic people.

Nobody in all the groups (often two per week) and weekends for myself that I attended ever mentioned the word ‘diagnosis’- many simply resolved their problems. I was not trying to be ‘cured’ of anything either, if a you went to a group, you went to work – no matter who you are or where you are at, you can always work on something- that is the education of therapy – learning growth processes. My sudden and startling realization in 1977 one day as I was by myself that I was fully alive was an unexpected bonus.

I doubt that environment could arise again – now it seems everyone is obsessed with their ‘diagnosis’ and well they should – the APA diagnosis can destroy their lives and even kill them.

Report comment

“Julia on May 16, 2012 at 5:03 pm said:

In short, all the ways our government tries, for better or for worse, to create a level playing field for people with mental disorders.

..

How we handle these issues now is far from perfect.”

—–

You need to stop drinking the PharmaProp Koolaid. The Government has been bought by PharmaCorp.

And there is no ‘we’. “We’ don’t handle anything, ‘they’ do. When they come to your door to take you off for forced drugging, try telling them about the ‘we’.

Report comment

The topic of “mental illness” covers a broad spectrum of situations that we face as humans.

Behavioral challenges, learning disabilities, sudden altered states of minds, physical injuries, diseases that manifest with psychological components, age related mental changes, etc.

Regarding psychosis and mania:

By consensual agreement within the American Psychiatric Association psychiatric diagnoses are descriptive labels only for phenomenology, not etiological or mechanistic explanation for syndromes. Thus, a psychiatric diagnosis labels a pattern of signs and symptoms, but offers no hypothesis concerning the mechanism(s) of the clinical phenomena.(Davidoff et al.,1991).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classifies psychotic illnesses as “Psychosis Due to General Medical Conditions”, and “Substance Induced Psychosis”. (DSM-IV Codes 293.81 & 292.11).

Distinguishing medical conditions and substance-induced psychosis from schizophrenia or Bipolar disorder through clinical presentation often is difficult.

Psychosis Due to a Medical Condition involve a surprisingly large number of different medical conditions, some of which include: brain tumors, cerebrovascular disease, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Creitzfeld-Jakob disease, anti-NMDAR Encephalitis, herpes zoster-associated encephalitis, head trauma, infections such as neurosyphilis, epilepsy, auditory or visual nerve injury or impairment, deafness, migraine, endocrine disturbances, metabolic disturbances, vitamin B12 deficiency, a decrease in blood gases such as oxygen or carbon dioxide or imbalances in blood sugar levels, and autoimmune disorders with central nervous system involvement such as systemic lupus erythematosus have also been known to cause psychosis.

A substance-induced psychotic disorder, by definition, is directly caused by the effects of drugs including alcohol, medications, and toxins. Psychotic symptoms can result from intoxication on alcohol, amphetamines (and related substances), cannabis (marijuana), cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, phencyclidine (PCP) and related substances, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, and other or unknown substances. Psychotic symptoms can also result from withdrawal from alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, and other or unknown substances.

Some medications that may induce psychotic symptoms include anesthetics and analgesics, anticholinergic agents, anticonvulsants, antihistamines, antihypertensive and cardiovascular medications, antimicrobial medications, antiparkinsonian medications, chemotherapeutic agents, corticosteroids, gastrointestinal medications, muscle relaxants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, other over-the-counter medications, antidepressant medications, neurleptic medications, antipsychotics, and disulfiram . Toxins that may induce psychotic symptoms include anticholinesterase, organophosphate insecticides, nerve gases, heavy metals, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and volatile substances (such as fuel or paint).

Before assigning the diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder or Schizophrenia due diligence should be asserted in the clinical evaluation of psychotic and manic symptoms to address “Psychosis Due to General Medical Conditions”, and “Substance Induced Psychosis” (DSM-IV Codes 293.81 & 292.11).

Improvements in the diagnostic accuracy and treatment of psychosis is cost-effective for both the mental health consumer and society. Advocacy for mental illness must include the consideration of underlying etiological factors of psychiatric symptoms.

If you are looking for research and case studies regarding underlying causes of psychosis and mania here is a site that lists many of them:

http://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/

Report comment

In my opinion, mental health advocates need to collaborate on making alternative and complimentary options available.

The diverse membership of the International Society for Ethical Psychology and Psychiatry (ISEPP) is the main reason why I chose to become a member and be a dedicated volunteer.

Membership includes psychiatrists, psychologists, professional clinical counselors, academic researchers, educators, lawyers, psychiatric survivors, concerned family members, other mental health professionals, and advocates.

Members of ISEPP are the parents who lost children, individuals who were harmed by psych meds and mental health professionals who testified at FDA hearings to get black box warnings on psych meds.

…

Since I am not a mental health provider I feel it is important to support those who are in the position to provide non-drug alternative options to individuals who are seeking help.

At this point, the evidence is clear. While all the king’s horses and all the king’s men are still assessing, or contributing to the core problems in the mental health care system, we are overlooking the real sickness, the schizophrenic nature of mental health advocacy.

Why do advocates waste so much time in adversarial conversation and so little time on finding ways to advocates for ethical, best practice solutions?

Advocates should be collaborating on ways to get affordable, evidence-based help to children who are battling learning disabilities, behavioral challenges and emotional difficulties.

I was thrilled to see this decision by a Federal Judge in Fl that has the potential of preventing parents/educators to choose medication management over Applied Behavioral Therapy for symptoms of autism because they could not afford the safer option.

Child advocates should be celebrating this victory, regardless of affiliations to organizations.

http://isepp.wordpress.com/2012/05/15/what-are-affordable-ways-to-help-develop-social-behavioral-and-cognitive-skills-when-dealing-with-autism/

Report comment

Hi Tim

Nice blog. A couple of little things. Foucault (Birth of the clinic) speculates the birth of the ‘medical model’ or ‘germ-theory’ = specific silver bullet – back to some Parisean clinics in 1800. One of the things that makes Foucault’s story interesting is that most of the senior doctors were off at the Napoleonic wars, and in little clinics around Paris, not the main hospitals, is where this new paradigm came in being – ‘nek minit’ there was a rush for cadavers, grave robbing began, as they went to search for diseased tissue, etc etc. Pasteur was an expression of this new ‘gaze’. I think we are seeing some parallels now as the mainstream services get more entrenched in the medical model ‘gaze’ – especially driven by defensive medicine and financed by big pharma – whilst in numerous small clinics an emerging number of clinicians are appearing that view their work through what Wampold calls the ‘contextual model’ lens. This view highlights ‘common factors’ research (things all therapies have in common).

Now where this gets interesting is in this conversation with colleagues that you list. As the contextual model stresses the active engagement of both client and therapist in a meaningful ritual intended to be healing; agencies looking at their work through the contextual model are having conversations with each other as to whether you and your client are actively engaged – as the research suggests this is the important thing. There is not so much conversation in these agencies about the problem itself.

Thank you once again for this blog

Report comment

Kathe Skinner, M.A., L.M.F.T.

on June 2, 2012 at 11:04 am said:

As long as we need insurance to fund access to mental health professionals (including psychiatrists, counselors and therapists)the requirement for diagnoses, and thus labeling, will continue. We forget that business, not patient needs, drive the medical profession (e.g., the 12 minutes pcp’s spend with patients in order to be cost-effective). Let’s not leave out most doctors and hospitals from this description, either.

More to the sociological point, mental disorders continue to carry a stigma, maybe even more so in a society that values and seeks “perfection”. I am always surprised at how long my 20-something clients wait before seeking counsel; fearing what others (even themselves!) will think. Of course, there are people with mental health disorders we ought to avoid, like sociopaths or paranoid schizophrenics, but many of us – 15-17 million Americans, more than AIDS, cancer, or heart disease according to the NIMH — encounter depression each year. Depression benefits from medical intervention as much as cancer benefits from psychotherapy. I believe that most everything that happens to us human beings is a biopsychosocial event, inextricably intertwined with all that we are. Optimizing who we are, treating ourselves well, calls for us to seek out many interventions as a natural part of the human experience. It’s too bad we’ve allowed some of those interventions to be such hot potatoes.

Report comment