The Indian Health Service (IHS), the main resource for health care for enrolled Native Americans in the United States, represents an extension of treaty rights. To remind you, Article VI of the U.S. Constitution states:

“[A]ll treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land…”

Not that this enshrined idea has held much credibility for indigenous people across North America over the years, but that’s what the Constitution says. By mentioning it, I mean to clarify that for many members of the 564 federally-recognized tribal communities (carrying the politically-meaningful but racially-fictional label, ‘Native American’) access to health care has already been a right for some time, a treaty right, and never an ‘entitlement.’ By contrast, members of the 100 or so still ‘unrecognized’ native communities across the U.S. (some of which do have state recognition) are not entitled to access the Indian Health Service system.

The fact that the IHS, a descendent of the U.S. Public Health Service, continues to provide health services appears particularly encouraging, especially when one considers people in Indian Country have the lowest life expectancy, and highest rates of diabetes, poverty, crime victimization, and suicide of any ethnic category in the U.S. census.

The sweep of service provision is quite wide. IHS provides comprehensive health care to about 1.9 million of the 4.3 million enrolled American Indian and Alaska Natives in the U.S.1 with a total 2014 annual budget of nearly $4.6 billion, of which $266 million is allocated to mental health and substance abuse programs.2 But the need has always outstripped capacity, and the IHS budget has increased at barely the inflation rate for health care, despite enjoying its first expansion in many years under President Obama.

Indian Health Service itself offers exceptional opportunities for its critics, including criticisms from its overseers. Conservatives turned to the chronic malfunctions at IHS as ammunition against proposed Obamacare, and later on, to help skewer Obamacare’s launch issues. Yet another of many demands to fix IHS agency ‘dysfunction’ came last May from Indian Affairs Committee Chair Senator John Tester (D-MT), who built on efforts of past chair and former Senator Byron Dorgan and his committee. Dorgan led a bilateral committee investigation of the IHS Billings, MT region back in 2010, which found, according to Derek Wallbank of the Minneapolis Post:

- IHS employees “with a record of misconduct” were frequently reassigned or placed on paid administrative leave rather than being terminated. In some cases, employees stayed on the federal payroll for more than a year without working.

- Employees stole narcotics from some facilities, and almost all of those facilities that weren’t stolen from had inadequate controls to prevent narcotics theft.

- IHS failed to ensure that its employees maintained current licenses, and didn’t provide evidence it was aware of cases where employees state licenses were revokes or suspended.

- Most IHS facilities in that region are now at risk of losing their Medicare and Medicaid certification.3

I worked as an IHS psychologist from 2000 to 2004 and personally witnessed similar disturbing practices all around me at that time. I’ll likely hark back to encounters with those IHS dysfunctions from time to time on this blog, but I want to make an important point right away with respect to understanding at least some of them:

- Follow the money.

Like many managers of poorly-funded programs serving the poor, IHS administrators are highly motivated to find cash in creative, possibly desperate ways. This is probably how IHS mental health programs came to rely on Medicaid reimbursement to offset chronic underfunding.

Being a ‘Comprehensive Rehabilitation Facility’ (Inpatient and/or Outpatient) under Medicaid allows a particular IHS facility to bill for ‘encounters’ at specified rates. For example, an outpatient Medicaid encounter may be defined as a face-to-face meeting between a ‘patient’ and a health care provider of at least 5 minutes (most encounters would be more likely coded at 10 minutes or more). Rates vary by state, but the current encounter rate for an IHS Medicaid patient in the state of Washington (where I live) is $294.00.4

Traditionally (an ironic word in Indian Country), a counseling or therapy session with an individual or family is usually thought of as taking about 50 minutes. Thus, listening and talking as a psychologist or counselor with a ‘patient’ at IHS about problems in living life could represent ‘one encounter’ under Medicaid, i.e. $294 (where I live).

However, a psychiatric nurse can provide a ‘medication management’ meeting at a frequency of three or more encounters during this same amount of time, i.e. $882.

You begin to understand. This was how I came to understand why an independently-contracted psychiatric nurse was paid at about the same annual rate as my yearly full-time IHS salary in 2002—while putting in only two days per week at our clinic. Rolling kids (and their parents) through 20-minute ADHD evaluations was a routine practice of this colleague. Whole Indian families began to have hyperactivity and attention issues. A closet economy awoke on the reservation—4 hits of Adderall for $10 was the last street price I heard. Indian Health Service was a big supplier. I recall when nine elementary school Indian children overdosed on imipramine after being told by a peer they’d all be getting high together. The medication had been delivered to a minor picking up a prescription for an adult family member at our Indian Health Clinic.

I became concerned about all this, but it only got me in trouble when I brought it up. Medicaid—with its intrusive, unbelievably cumbersome and bureaucratic record-keeping and billing system was and is providing a supplemental cash cow for Indian Health Service’s meager budget. I was informed as a non-medical professional, I was out of my job description and shouldn’t rock the boat. Since my time, the Indian Health Service has authorized prescription authority across all its facilities for psychologists trained in pharmacotherapy.

Medicaid is not the only incentive within the IHS mental health system for labeling and medicating indigenous people instead of talking to them and their families about their historical and current circumstances and related emotional and behavioral fallout. A Western biopsychiatric ‘cultural’ ideology dominates the Indian Health Service’s Mental Health Manual5, the official policy and procedure manual for federally-delivered mental health help in Indian Country.

Don’t be deceived into thinking tribally-managed programs are exempted from the structure imposed by this manual—they have to follow its tight template in order to maintain their IHS-approved grant funding under Public Law 638, which allows tribes to take over and ‘self-manage’ federal programs. With Orwellian irony, tribes deciding to exercise PL 638 and seeking to ‘independently manage’ mental health programming must follow IHS guidelines stipulated in this Mental Health Manual in order to retain their federal funding.

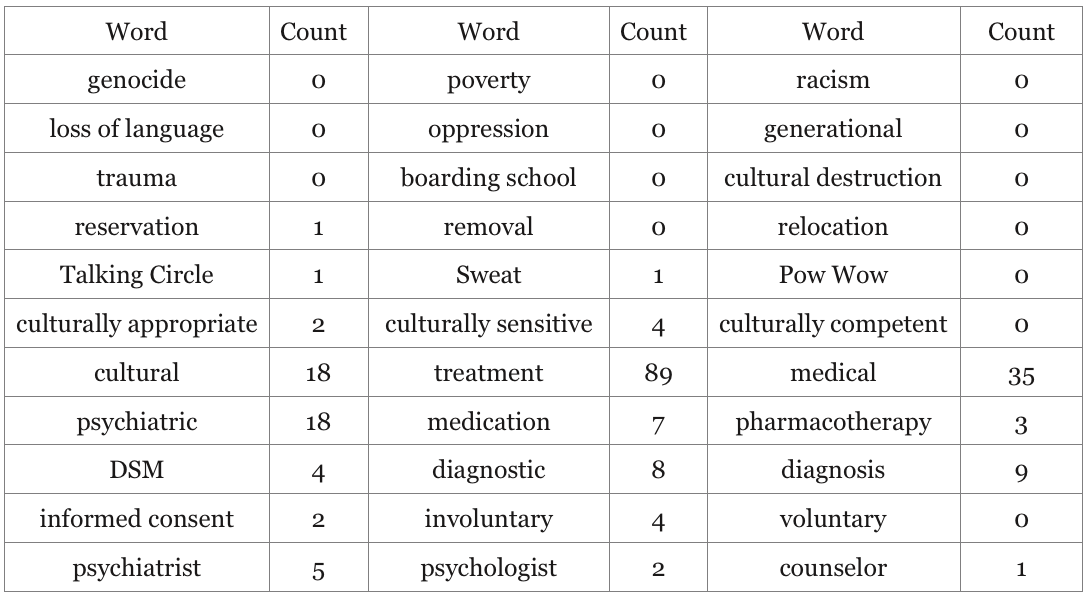

One way to demonstrate how this biopsychiatric culture dominates is to offer you a simple word count from within the IHS Mental Health Manual.

I chose the following list of words by asking myself: What are the ‘keywords’ one hears pertaining to the psychological well-being of native people, overheard at indigenous wellness conferences, in indigenous commentary and research, keynote addresses, and within every day conversations with American Indian and Alaska Native tribal members?

The resulting table is below. You may find it interesting to go to the link yourself at the end of my post and do your own searching for words (control ‘f’ for pc’s, and command ‘f’ for Macs). I’d be interested in what you discover.

Detecting the True ‘Culture’ of Indian Health Service Mental Health Programs By Counting Words

It’s tragically unsurprising to me to detect so many uses of the word ‘cultural’ in the IHS Mental Health Manual alongside so few words that actually pertain to the shared cultural-historical experiences and resiliencies of American Indian and Alaska Native people.

If we take the most representative words for what’s in this manual, the true ‘cultural’ predilection of mental health services to Native Americans coming to the Indian Health Service is ‘psychiatric medical treatment’ emphasizing ‘diagnosis’ and ‘medication.’

The idea that the word ‘culture’ in the Indian Health Service Mental Health Manual has anything to do with the rich and varied healing traditions of American Indians and Alaska Natives appears to be a convenient accident.

* * * * *

References:

1 Office of Inspector General, Access to Mental Health Services at Indian Health Service and Tribal Facilities

2 Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service, 2014, Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees

3 ”Senators Demand National Investigation into Indian Health Service Mismanagement,” Derek Wallbank, Minnpost Online, 9/30/10,

4Department of Social and Health Services, Medicaid Purchasing Administration, Memo 11-44

5U.S. Indian Health Service, Indian Health Manual, Part 3 – Professional Services, Chapter 14-Mental Health Program,

Oh wow, I think you just illustrated three of my favourite theories:

1 one of psychiatries main functions is to be the drug delivery agent for big pharma

2 another of psychiatries functions is to make sure no one thinks about why people are distressed

3 neo-liberal economic funding paterns are a foul way of delivering health care and social services leading to services cutting costs by implimenting easy to administer systems that look good on the books but which do not answer clients problems.

Report comment

Thanks so much for your comment, John. I’m with you on all points except your last (I may not quite get your intent)–I believe the mish-mash of various political agendas creating this dysfunctional system are learned behaviors across generations that re-perpetuate the so-called ‘mental health problems’ that big pharma’s psychiatrists sedate and medicate. The political struggles are incorporated into the entire dysfunctional system. The polarities fight it out, but nothing really gets fixed. I’m hoping we can somehow step outside, take a longer view, see how we got here, and bust the whole paradigm. Best, Dave

Report comment

you wrote: “Follow the money”

When lots of social service agencies compete for small pots of money from a big pot, usually government, it often results in managers pushing workers to do shoddy work and impliment quick fixes such as the ones you outlined above. It makes it harder for the real work of understanding what is going on with a perticular client or for a whole community.

The funding model and giving business a bigger say in public life, such as evidenced by the power of Big Pharma makes it much harder to unlearn the behaviours you have outlined above.

Report comment

Excellent, John. I understand what you mean and agree, my ‘meta-systemic preoccupations’ notwithstanding.

Report comment

Thanks for this. I really enjoyed listening to your appearance on Madness Radio late last year (http://www.madnessradio.net/madness-radio-indian-country-psychology-david-walker/), so I am happy to see you now blogging here.

Report comment

Yes, thanks so much, uprising. I really appreciated Will Hall giving me a chance to say a few things on his wonderful show. Thanks for posting the link to that. I also have the interview on my website, along with my dandy new book trailer–www.tessasdance.com (I had to put in a plug for it). Best, Dave

Report comment

It’s so sad… Just looking at this table shows one exactly what is wrong with psychiatry.

Report comment