From GatherFor/Medium: “Maslow spent six weeks living at Siksika — which is the name of the people, their language, and the Blackfoot Reserve — in the summer of 1938. His time there upended some of his early hypotheses and possibly shaped his theories . . . Whereas mainstream American narratives focus on the individual, the Blackfoot way of life offers an alternative resulting in a community that leaves no one behind.

. . . According to Blood and Heavy Head’s lectures (2007), 30-year-old Maslow arrived at Siksika along with Lucien Hanks and Jane Richardson Hanks. He intended to test the universality of his theory that social hierarchies are maintained by dominance of some people over others. However, he did not see the quest for dominance in Blackfoot society. Instead, he discovered astounding levels of cooperation, minimal inequality, restorative justice, full bellies, and high levels of life satisfaction. He estimated that ‘80–90% of the Blackfoot tribe had a quality of self-esteem that was only found in 5–10% of his own population’ (video 7 out of 15, minutes 13:45–14:15). As Ryan Heavy Head shared with me on the phone, ‘Maslow saw a place where what he would later call self-actualization was the norm.’ This observation, Heavy Head continued, ‘totally changed his trajectory.’

. . . Maslow then wondered whether the answer to producing high self-actualization might lie in child-rearing. He found that children were raised with great permissiveness and treated as equal members of Siksika society, in contrast to a strict, disciplinary approach found in his own culture. Despite having great freedom, Siksika children listened to their elders and served the community from a young age (ibid, minutes 16:35–17:07) . . .

Differences Between Maslow’s Theories and Blackfoot Beliefs

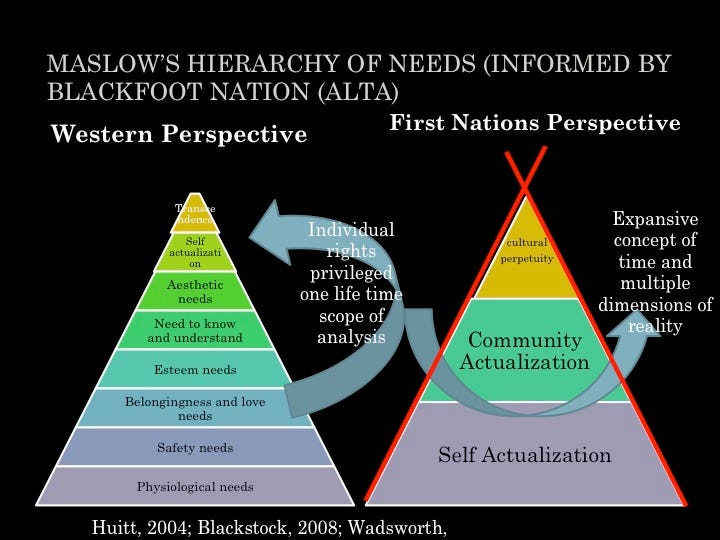

. . . To help explain the different emphases of the Western worldview and the views of First Nations, Dr. Cindy Blackstock, herself a member of the Gitxsan tribe who interviewed members of the Blackfoot Nation, created the illustration below (Michel, 2014):

Blackstock makes clear that there is great diversity among First Nations, but the above diagram captures some of the similarities she’s found in her study of them, including the Blackfoot. I summarize my understanding of her diagram below.

Self-Actualization

Maslow appeared to ask, ‘how do we become self-actualized?’ Many First Nation communities, though they would not have used the same word, might be more likely to believe that we arrive on the planet self-actualized. Ryan Heavy Head explained the difference through the analogy of earning a college degree. In Western culture, you earn a degree after paying tuition, attending classes, and proving sufficient mastery of your area of study. In Blackfoot culture, ‘it’s like you’re credentialed at the start. You’re treated with dignity for that reason, but you spend your life living up to that.’ While Maslow saw self-actualization as something to earn, the Blackfoot see it as innate. Relating to people as inherently wise involves trusting them and granting them space to express who they are (as perhaps manifested by the permissiveness with which the Siksika raise their children) rather than making them the best they can be. For many First Nations, therefore, self-actualization is not achieved; it is drawn out of an inherently sacred being who is imbued with a spark of divinity. Education, prayer, rituals, ceremonies, individual experiences, and vision quests can help invite the expression of this sacred self into the world . . .

Community Actualization

As Maslow witnessed in the Blackfoot Giveaway, many First Nation cultures see the work of meeting basic needs, ensuring safety, and creating the conditions for the expression of purpose as a community responsibility, not an individual one. Blackstock refers to this as ‘Community Actualization.’ Edgar Villanueva (2018) offers a beautiful example of how deeply ingrained this way of thinking is among First Nations in his book Decolonizing Wealth. He quotes Dana Arviso, Executive Director of the Potlatch Fund and member of the Navajo tribe, who recalls a time she asked Native communities in the Cheyenne River territory about poverty:

‘“They told me they don’t have a word for poverty,” she said. “The closest thing that they had as an explanation for poverty was ‘to be without family.’” Which is basically unheard of. “They were saying it was a foreign concept to them that someone could be just so isolated and so without any sort of a safety net or a family or a sense of kinship that they would be suffering from poverty.”’ (p. 151)

. . . As Blackfoot scholar Billy Wadsworth (of the Blood, or Kanai Tribe) summarizes in dialogue with Cindy Blackstock (2011), Maslow did not ‘fully situate the individual within the context of community.’ If he had done so, and also more deeply integrated the Blackfoot perspective, ‘the model would be centered on multi-generational community actualization versus on individual actualization and transcendence.’

Maslow himself may have agreed with this critique. Scott Barry Kaufman (2020) shares an excerpt from an unpublished Maslow essay from 1966, 23 years after he published his paper on the Hierarchy of Needs, called ‘Critique of Self-Actualization Theory,’

‘self-actualization is not enough. Personal salvation and what is good for the person alone cannot be really understood in isolation. The good of other people must be invoked as well as the good for oneself. It is quite clear that purely inter-psychic individualist psychology without reference to other people and social conditions is not adequate.’

What else emerges when we see the individual as deeply situated in community?

Circles, Not Triangles

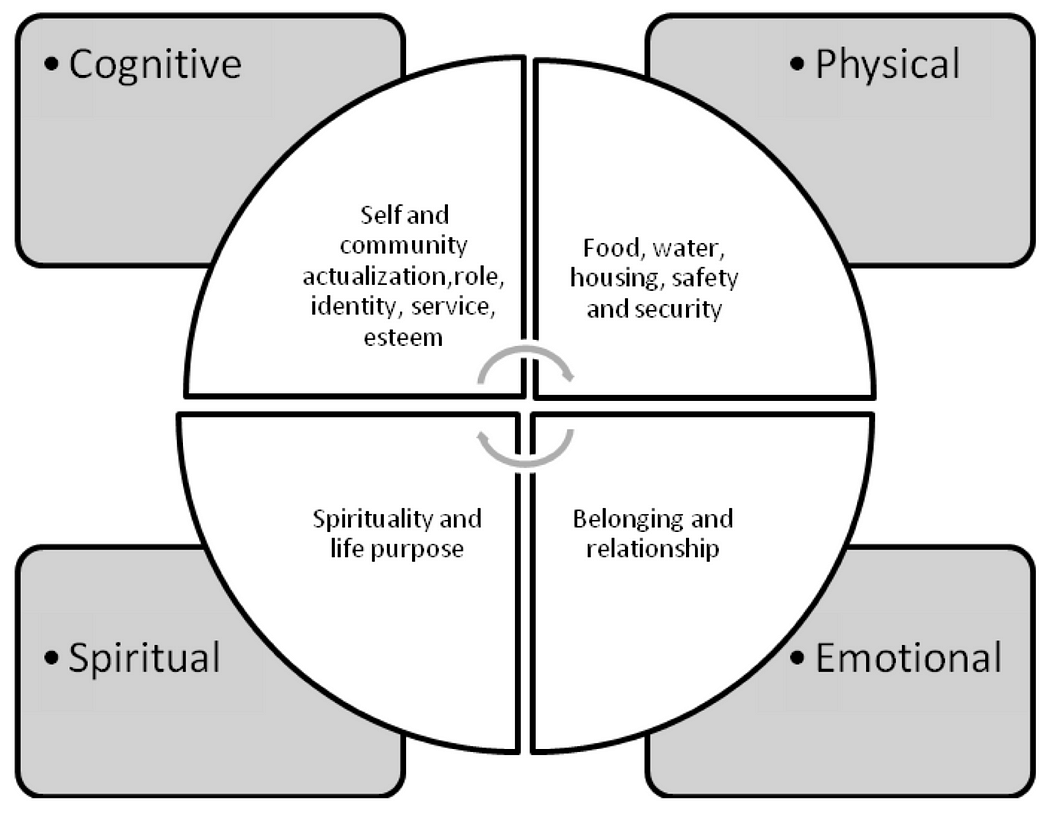

The triangular models above suggest that there’s a place to start meeting our needs and a place we end up. But is it true that our needs follow Maslow’s hierarchy of ‘prepotency,’ where some needs consistently take priority over others? Maslow (1943) himself indicates there are many exceptions to his hierarchy and Blackstock (2011) agrees, citing Seneca First Nation member and psychologist Terry Cross:

‘Cross (2007) argues that human needs are not uniformly hierarchical but rather highly interdependent […] [P]hysical needs are not always primary in nature as Maslow argues, given the many examples of people who forgo physical safety and well-being in order to achieve love, belonging, and relationships or to achieve spiritual or pedagogical objectives. The idea of dying for country is an example of this as men and women fight in times of war.’

Blackstock represents Cross’ ideas in the circular model below:

This circular model reveals thinking in line with many First Nations: depending on the situation, the order in which our needs must be met is subject to change. A circular model captures the inter-relatedness of our needs and helps highlight that we can experience needs simultaneously and in changing order. This way of viewing needs makes more sense when seeing an individual as deeply rooted in a community, especially because a community is capable of meeting multiple needs in parallel. While one individual is cooking, another may be keeping children safe, while another may be negotiating peace with people from other tribes . . .

Why Haven’t We Heard About the Blackfoot Worldview Before?

Though Maslow saw full bellies, low inequality, and rates of self-actualization at 80–90%, why didn’t he alert the world to all we could be learning from the Blackfoot? He clearly held them in high regard, as he indicated in journals and in his biography.

It’s possible that Maslow may have faced dismissal if he had publicized Blackfoot teachings. Dr. Richard Katz, author of Indigenous Healing Psychology: Honoring the Wisdom of First Peoples, Harvard professor, and personal friend of Maslow’s speaks to this point in a podcast conversation with Scott Barry Kaufman (minutes 28:50–32:20). He says he never spoke directly with Maslow about this, but postulates that Maslow may have been concerned that elevating Siksika teachings might diminish the validity of the ideas he was putting forth. Such barriers to Indigenous contributions have remained in academia until today (Blackstock, 2019).

Despite the fallibility of our mainstream institutions, publicly challenging prevailing worldviews is risky business. Galileo’s elevation and defense of the Copernican heliocentric solar system, for example, led to his being labeled a heretic by the Catholic Church and placed under permanent house arrest.

By offering compelling alternatives, Indigenous worldviews pose a threat to our status quo. Lakota Medicine Man John Fire Lame Deer offers one poignant contrast between the world he grew up in and the world of ‘the white man’:

‘Before our white brothers came to civilize us we had no jails. Therefore we had no criminals. You can’t have criminals without a jail. We had no locks or keys, and so we had no thieves. If a man was so poor that he had no horse, tipi or blanket, someone gave him these things. We were too uncivilized to set much value on personal belongings. We wanted to have things only in order to give them away. We had no money, and therefore a man’s worth couldn’t be measured by it. We had no written law, no attorneys or politicians, therefore we couldn’t cheat. We really were in a bad way before the white men came, and I don’t know how we managed to get along without these basic things which, we are told, are absolutely necessary to make a civilized society.’ (Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions, p. 70)”

***

Back to Around the Web