Sciences have peaceful periods and torrid times — “normal science” and “scientific revolutions”, as Thomas Kuhn called them. Revolutionaries have strong feelings about their subjects but they rarely self-describe as revolutionaries, especially in science. By necessity, their focus is narrower. Young scientists (the ones with bold new ideas) defend the photo-realism of their brushstrokes more than the general impression of their canvas. The revolution is slow. Little by little, it spans an entire career and it does so unnamed.

One of these revolutions, as bold as Darwin’s, has been gently smouldering for the last twenty-five years and it’s about to combust. It’s about our wellbeing.

“Mental illness” and “neurodiversity” might sound like brethren ideas. They are, after all, about the same phenomena. But like fire and water fighting for the same piece of wood, they can’t both succeed. In technical terms, they are competing paradigms; contestants in a scientific revolution.

“Mental illness” and “neurodiversity” might sound like brethren ideas. They are, after all, about the same phenomena. But like fire and water fighting for the same piece of wood, they can’t both succeed. In technical terms, they are competing paradigms; contestants in a scientific revolution.

In 1998, Judy Singer coined “neurodiversity”. With just one word, she moved the lens — from “mental illness” and its hospital drip-trolley vibes, to biodiversity, natural, strong and dignified. Singer drew from the social model of disability, which brings attention to the disabling thing (think: stairs for a wheelchair owner or text for a dyslexic). Before that, the medical model of disability diagnosed people’s distress by examining only the person, rather than the person-in-their-environment.

The medical model’s lens had unintended consequences. It enfeebled the people it was tasked with empowering. It made them dependent. And their dependency became dollars for medicine. Dollars are hard to walk away from. And so it makes sense that the American Psychiatric Association and its international cousins retain that lens, even today. Judy Singer’s revolution would not be over in a day.

Scientific revolutions are fought over phlogiston and oxygen, over waves and particles, background radiation, dark matter and tectonic plates. They are fought by scientists with skin in the game. They fight for their reputations and jobs. Rarely, however, are they fighting for their lives. That’s what makes this revolution special. Neurodiverse people, like Judy Singer, aren’t just fighting to exist in the conversation. They’re fighting to exist at all.

Oxygen doesn’t get to speak for itself. If it did, I wonder what it would say?

Quit boiling me off to figure me out. Trust me when I tell you who I am. I know.

How foolish would a chemist be to not listen to oxygen and keep calling it “phlogiston”? To continue to plug away in a lab when they could just ask and believe the answer.

I asked a neurodiverse crowd, “What do you feel when someone suggests you’re ‘living with a mental illness?’” They replied:

@Bxx: eye roll until my face turns inside-out

@Bxx: That makes my stomach drop, extremities tingle, and ears ring.

@Cxx: I feel discounted, belittled, shamed & surprised

@ixx: I feel the RAGE

@Fxx: it makes me feel like I have to explain things very slowly with very small words. I tense up, I experience irritation

@Hxx: i’m never gonna talk to you again if you say that.

@uxx: shut down, like the lid of a box is closing on my head

@Exx: Frustrated, alienated, defensive, tense.

@Cxx: I feel dread, a sense of tightness and unease in my body

@nxx: Angry, rejected, tired as all hell

@mxx: I feel discredited and written off, like all my accomplishments are nothing. Like I’m just some crazy person

@Nxx: Nauseated. Critiqued. Dismissed.

@lxx: Oof, immediately activated and sick tummy, like I want to run.

@Wxx: Nauseous, pissed, unseen, dismissed, bullied.

These people are writhing against “the Personal Tragedy model” of neurodisability. I share their discomfort at being labelled “ill”. Although I experience distress acutely, I don’t have a disease, a bug, or an error. I have a body. I have a nervous system. And just like everyone else, when my circumstances are untenable, my body protests.

Medical science has had great success in finding and labelling disease-causing bugs like bacteria and viruses which nobody doubts are real things. Yet in their search for such bugs of the mind, they have had so little success that philosophers publish papers and go to conferences built around the question, “are these things even real?”

There are two simple reasons why experts continue to search for psyche-bugs despite over a century of abject failure. One of those is germ theory.

Germ Theory

Germ theory is a fundamental concept in modern medicine that posits that many diseases are caused by microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi. The development of germ theory in the 19th century revolutionized Western medicine, leading to significant changes in our view of disease, hygiene, and public health. It became the scaffold for western medicine’s ownership of “health”.

Psychology and psychiatry are not the first to hunt enthusiastically for a germ that isn’t there. Pellagra is a disease characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia, which can be fatal if left untreated. It was widespread in the United States and Europe, particularly among the poor, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the early 20th century, Dr. Joseph Goldberger, a physician and epidemiologist working for the United States Public Health Service, was tasked with investigating the cause of pellagra. Goldberger conducted a series of studies in search of the elusive germ that caused the disease.

However, his research led him to conclude that pellagra was not caused by an infectious agent, but rather by poor diet. He discovered that the disease was associated with a lack of fresh vegetables, fruits, and protein in the diet, which was common among poor, mostly black, populations in the southern United States. He was able to induce and cure pellagra in experimental subjects by modifying their diets, demonstrating the crucial role of nutrition in the disease.

Goldberger’s findings were met with resistance from many physicians and public health officials who were reluctant to accept that pellagra was not an infectious disease. He had a fire on his hands, not unlike the fire that Judy Singer kindled one hundred years later. This time, it’s not just a few medical careers and reputations at stake. It’s the $36 billion psychopharmaceutical industry and psychiatry itself. These two industries together, along with hospitals, insurance, and legal infrastructure, are known as the psychiatric-industrial complex. Not exactly the same size as the military-industrial complex, but bigger than the prison-industrial complex, this giant lends its heft to the notion that distressed people have a disease.

In places where no bugs exist, medical science will even transmute parts of the human organism itself into a bug so as to fight it. Remember the Human Genome Project? “When we’ve mapped the entire genome, disease will become a thing of the past!” We heard this claim not from overcaffeinated futurologists but from esteemed scientists. The logic was, “if we understand the source code for the construction of a human, we can correct the bugs”. If they weren’t wearing a labcoat and speaking in Latin, we’d notice that they were proposing eugenics.

And then it was the human brain map — if we can just know everything physical, we can find the fault. But measuring skulls with finer and finer instruments is still measuring skulls. A $500 million version of this frenzied search was recently announced to similar promise. Many fascinating things will be uncovered, but it won’t be “the bug” because the bug doesn’t exist. Our distress isn’t a mistake. It’s us reacting as nature intended us to react when circumstances are untenable.

A thoughtful objection to this, um, objection, is, “but surely some things are biological errors. What about, say, people who are born “missing” a limb?” To which one only has to reply, “missing according to whom?” To make a mistake, there must first be an idea of what is correct. And animals aren’t “right” or “wrong”. They just are. Human beings, in their infinite wisdom, made up the idea of a “good” or “bad” or “correct” or “incorrect” person. Such ideals are so pervasive that even the pathologized lean into them. These are the people who gain comfort from hearing from a doctor say, “your suffering is real. It’s because of your biology.” In another time it was a priest saying “your suffering is real. It’s because of the demon.” For people whose suffering has been denied, these suggestions are powerful indeed.

Madness has long sought an explanation and many have tried it. Poets, sages, preachers, doctors, historians and judges have weighed in. Over the previous century, one of these collectives has stamped its authority — psychiatry. Psychiatric classification is king. The American Psychiatric Association publishes a diagnostic manual every five to ten years which arranges new and old “symptoms” under headings like “Prolonged Grief Disorder” or “Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified”. Under each such heading you will find diagnostic instructions like, “must exhibit a pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with their functioning or development, with symptoms present before the age of 12.” It’s quite a volume:

“Over two inches thick and with a thousand pages, it’s unlikely to find its way to many beaches.” (https://thenewinquiry.com/book-of-lamentations/)

Dry as it may be, it sells out every time. Its theology is having a moment. But it’s fast losing its prestige. Even psychiatric practitioners themselves are getting the gag. They sense the drugs they’re prescribing aren’t as magic as we thought. And there is the second reason the medical model is so hard to shake—big pharma:

“Psychopharmacology is in crisis. The data are in, and it is clear that a massive experiment has failed: despite decades of research and billions of dollars invested, not a single mechanistically novel drug has reached the psychiatric market in more than 30 years.” (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3406532/)

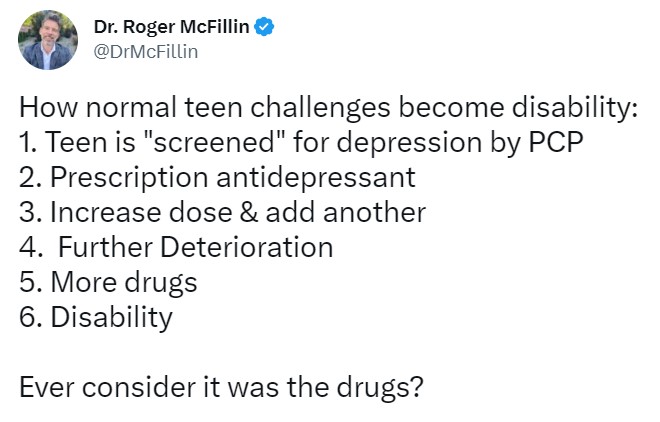

Alongside practitioners’ growing doubt about the realness of psychiatric nosology are their doubts about the drugs they’re supplied with. As one clinical psychologist recently asked:

Whether burning about the chemistry or the “illnesses”, the fire inside medical-industrial’s machinery targets ever-shifting phenomena. Presentations of human distress shift across time, culture, and identity. To capture one “illness” across these spectra inside a diagnostic text is a task no more achievable than to capture the diversity of life inside one zoo. Should we even try?

Paradigm shifts

Conveniently for us, one of the most cited texts on earth sidesteps our ontological puzzle by telling science’s history—by telling stories. Thomas Kuhn, in the Structure of Scientific Revolutions, reimagined the way knowledge shifts over time. Rather than progressive, in a straight line, his history describes periods of “normal science” interrupted by revolutions.

Incommensurability

During a revolution, paradigms tussle and the humans who advocate for these frameworks talk right past each other.

“…the proponents of competing paradigms practice their trades in different worlds… Practicing in different worlds, the two groups … see different things when they look from the same point in the same direction.”

Kuhn labelled this feature ‘incommensurability’. We know it more colloquially as ‘cognitive dissonance’. Such dissonance is one thing when it’s a scrap about gravity. It’s another thing altogether when dignity and identity are on the line. Dissonance catches fire.

Dissonance happens over the question, “is this true?” Relief comes from asking, “what is happening?” instead. And here, what is happening is that power is shifting to a generation of people who a talking to each other at last. Escaped from the loneliness of psychiatric offices, we are now communicating with each other directly — via chat rooms in the ‘90s, on myspace in the ‘00s, and now on Zoom and Tiktok. It was an internet chat room of Autistics that brought Judy Singer to coin our clarion call in the first place.

“Neurodiversity” isn’t a cute new thing. It’s scientific revolution of huge importance. And unlike the revolutions before it, it is being led by the subjects of its study — by the collective power of our own voices.

But where is the science and what are the outcomes?

Report comment

The scientific-paradigmatic commentary is great here. But the deeper you apply the philosophy/sociology of science, the less it feels like it’s just technocratic/bureaucratic routine, or even pharmacological profiteering.

It begins to look like local and temporary prejudices enter the equation, such as: “a white middle class kid wouldn’t do that in this city” or “this isn’t what we usually do with black guys in this town”. Things like: “we expect this kind of behavior from a gangster black guy, but not from a white minister’s son” start to enter into the equation.

There’s no reason to believe that psychiatric practitioners are aware of their own local biases, or that they spend much time in other localities. It also doesn’t appear that a psychiatrist would question or seek to correct the biases of another psychiatrist, because they consider themselves to be scientific practitioners, rather than highly biased individuals.

If a psychiatrist in a redneck city labels someone a homosexual with no evidence, that label is likely to carry on in a progressive city, even though the progressive psychiatrist doesn’t hold the same prejudices. When reviewing each other’s notes, they ought to consider where the other psychiatrist came from.

When coupled with the “scientific” and bureaucratic problems in the field, the role of cultural bias is exacerbated. It now appears to be a free-for-all of localized prejudices, with the appearance of clinical objectivity. It looks like a police force that has the power to lock someone up, or say “get outta town!” And all of this is based on the very unscientific evidence of local gossip and slander.

Report comment

I find the term neurodiverse incredibly offensive and no better than the meaningless terminology it is meant to replace. I agree with much of what the author had to say but by using that term much of the target audience hears a dogwhistle and tunes out.

Report comment

https://youtube.com/@metabolicmind

Through the letterbox on my way down the garden path, a final note to say this.

There are no “right” or “wrong” animals. Animals just are. I believe I coined that phrase way back.

BUT I also say this, as all vets know….there ARE ill animals.

Animals that neurotically pee everywhere even in their beds. Animals that are miserable. Animals that are overly aggressive. Animals that seem disassociated and unresponsive. Unhappy animals. You take the animal to the vet and the vet asks…

“What are you feeding the animal on?”.

The vet does not so often say…

“This animal needs psychotherapy”.

No therapist asks that food question of the human animal. Are humans so egotistical as to think themselves beyond being just an animal? There IS a scientific germ, and it does have consequences on the brain. That germ is the mass industrial poison of sugar, spewing by the tonnage into the human animal’s well, that biohazard fuel tipped hourly into the oasis pool in the dry waddi.

That toxin is, in my opinion, one of the major reasons, though not the only reason, for all human and non human animals seeming to display signs of “neurodiversity”.

Please do check out the channel link.

But what I like about your article is the quite separate issue of how the world ought to accept individual “differences” and “differences in choice”. As this freedom to be as you want to be is highly medicinal of any misery. But by that very token, it is a freedom that should allow someone to say they do feel ill, and allow someone else to say they do not feel ill.

The freedom to declare yourself “ill” is part of the same freedom to declare yourself “different” or “normal” or “never ill”.

Freedom to be “different” is vital in life. Part of “difference” may be found in any individual saying…

“I feel ill in my metabolically dysregulated brain after binging on chocolate muffins at the oasis pool all my life”.

Or even, even, even…

“I feel ill in my brain because I have what I choose to believe is schizophrenia”.

Or even, even, even…

“I feel ill in my brain because I was traumatized at the sugary oasis pool by a creep selling me chocolate muffins”.

Or even, even, even…

“I feel ill in my brain because I am trying to spiritually transform through psychosis”.

THE ILL HAVE A RIGHT TO FEEL ILL.

That is one of their many “differences”, and the acceptance of “difference” is very healing.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I’m sorry but I find this article deeply confused because it’s not clear what exactly you mean to include in ‘neurodiversity’. You say it’s an alternative conception of mental illness but your article uses four different terms: disability, distress, neurodisability, and madness. Yet these terms are not at all synonymous or coextensive. ‘Distress’ is hardly all there is to mental illness. And a disability is by definition permanent. A revolution that defined everything we now call a mental illness as a disability would be catastrophic. It would essentialize the condition and suggests that it’s chronic and unchangeable, when in fact mental disorders are often transient or curable. So it would actually have the effect you’re accusing the medical model of, namely enfeebling the people it was meant to empower, by taking away their belief in recovery.

Of course, if, as you claim, disability is not an inherent characteristic of a person because it arises by reference to human ideals and in the context of human interactions (which is true), whereas the person ‘just is’, then you can’t claim that ‘identity is on the line’. That’s a direct contradiction. I’m also not sure how I am to square the notion of ‘neurodisability’ with the claim that ‘just like everyone else’, your distress is a reasonable response to your circumstances. How exactly is your brain disabled then? And how is ‘neurodisability’ different from a medical doctor telling you ‘your suffering is real. It’s because of your biology’? After all, a serotonin imbalance could be called a neurodisability (brain permanently unable to regulate serotonin).

Also I think you’re making the mistake of throwing out the baby with the bathwater by denying the importance of any kind of internal disease process in mental illness in favor of causation by ‘untenable circumstances’. I have often experienced distress and symptoms of mental illness while my circumstances were perfectly fine and not untenable at all, so they could very much be called ‘a mistake’. If the medical model fails by only looking at the person rather than the person-in-their-environment, your model fails because you don’t seem to want to look at the person at all. I guess that makes sense if you conceive of persons as having static disabilities or neurodiverse brain types that are products of nature (“us reacting as nature intended”) rather than having been shaped by the past in ways that can potentially be undone or improved. Just because biological psychiatry has not succeeded in elucidating the processes by which people come to be shaped by the past with ill effects, that doesn’t mean nobody has. Personally I think that claiming that psychology, psychoanalysis, trauma research and related disciplines have not produced any valid knowledge about mental illness in 100 years is the height of ignorance. Which is why the statement ‘Trust me when I tell you who I am. I know’ isn’t necessarily true. It took me years of studying to begin to understand who I was and what parts of my mental suffering I could reasonably expect to heal and what parts I couldn’t. Prior to that my ideas about myself were seriously flawed and hopelessly superficial. Obviously it can cause huge anguish if someone in a position of power (e.g. a psychiatrist) keeps overriding the way you’re feeling, but let’s not fall into the opposite mistake of believing that our own minds are fully transparent to us.

It’s fine to say that biological psychiatry is garbage, because it is, but someone will have to develop a viable alternative to it and given the multiple contradictions and confusions here, I don’t think this is it.

Report comment

I was doing ok reading your so-so comment until you said THIS: “or neurodiverse brain types that are products of nature (“us reacting as nature intended”) rather than having been shaped by the past in ways that can potentially be undone or improved.” Are you aware that being autistic evolves from Neanderthal and/or Denisovan hybridization with so-called “anatomically modern humans,” and that being autistic is a natual evolutionary neurotype of person expressing a high percentage of those other human neurotypes ? All humans are actually hybrids, just like when you breed a donkey to a horse. It’s just that some humans continue down a Dredd Scott – Buck v. Bell kind of delusion that they are all knowing, superior humans to all others, and a type of “pure-bred” “anatomically modern human,” which is not true. Again, we are all hybrids, a spectrum of hybidization of different human lineages, and you can’t just say being autistic ought to “be undone or improved.” That’s a massively inappropriate Eugenics attitude and ia very wrong. Autistic people bring many special skills and abilities to the betterment of all humankind, skills and abilities other neurotypes of humans don’t have. Autistic skills and abilities enhance the ability of all humans to survive. So, on account of that one statement, I have to really take issue with what you said. Neurodiversity is a thing, and it is real. Being autistic is neurodiverse, and we autistics are not lesser than anyone.

Report comment

Having had a brother who suffered with schizophrenia for over 35 years before he passed away and having known people diagnosed with various forms of mental illness I agree and disagree with the premise of this article. My Aunt who was in a wheelchair would have loved to walk again. She adapted to her condition and was able to make changes to her surroundings. She found her way through life.

Many of us, from time to time experience confusion, depression or other “symptoms” which have been labeled “illness”. But they can be an appropriate response to circumstances. Job’s friends got it right when they went to visit him and silently grieved with him for a week. They got it terribly wrong when they started blaming him for his misery and trying to fix him.

Some mental illness can and should be treated, oftentimes including medication. Other times people just need someone to listen empathetically. And sometimes it’s just the way it is and you have to learn to cope with the world. One size does not fit all, but in our assembly line world where efficiency and cost effectiveness are the most important metrics, people become invisible.

Report comment

Removed for moderation

Report comment

I am not at all convinced by the emerging ‘neurodiversity’ paradigm. As the commentators have said, it is not even clear what we mean by this term, but one of the most notable features of some of those who define themselves as ‘neurodivergent’ is the intensity with which they hold on to their diagnostic labels – typically, ‘ADHD’, ‘autistic spectrum disorder’ but also many others. Hardly an alternative to the diagnostic model, but some kind of strange supplement to it. In any case, what exactly is the ‘neuro’ bit here? Yes, let’s acknowledge and welcome diversity in all its forms, but the ‘wired differently’ claim for the ‘neuro’ bit has never been identified. We are all ‘wired differently’… and paradoxically, the rapidly expanding boundaries of what is called ‘neurodiversity’ is heading towards including all of us. So, then we will be back to square one.

Report comment

The freedom to be “different” means the freedom to call yourself what ever you like.

The freedom to “believe” means the freedom to have any understanding of who you are that you like.

Freedom is healing.

Being ordered to be “different” according to someone else’s insistence is not freedom. Being ordered to “believe” something that you do not is not freedom.

The free must be free to call themselves anything.

And the free must be free to not like the word “neurodiversity”.

Report comment

This article on the scientific revolution of neurodiversity is eye-opening! It’s essential to embrace diverse perspectives and challenge traditional views on neurological differences. Thanks for sharing this insightful piece!

Report comment