From Truthout: “During [the time of deinstitutionalization], a series of landmark legal cases, notably Lessard v. Schmidt (1972) and O’Connor v. Donaldson (1975), ushered in the strictest ever due process protections for people facing involuntary psychiatric commitment, resulting in a new legal standard. The state would now have to prove a risk of imminent danger to self or others in order to justify individuals’ deprivation of liberty.

There was almost immediate pushback from medical and family caregiver communities. In 1973, psychiatrist Darrold Treffert published an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry entitled ‘Dying with Their Rights On.’ Treffert referenced a number of tragic deaths of disabled people deemed not committable under the new laws. He argued that had they been eligible, these tragedies would not have occurred. These anecdotal examples were used as pretext for rolling back the clock to the previous ‘need for care’ standard.

This destructive rhetorical strategy continues to this day. Sixty years after deinstitutionalization began, politicians and pundits across the political spectrum falsely declare it to be a failure — when in reality, the vision has yet to be funded or realized.

And in a narrative that has gained traction among liberals, deinstitutionalization is blamed for houselessness and mass incarceration, expressed in the trope ‘prisons are the new asylums.’ Hospitals are dangerously framed as a ‘kinder’ alternative to jails, prisons and houselessness, leading to calls to ‘bring back the asylum.’ Pro-force activists falsely declare that the Housing First program, the gold standard for permanent supportive housing, has ‘failed‘ — in their view, yet another reason to reopen the institutions.

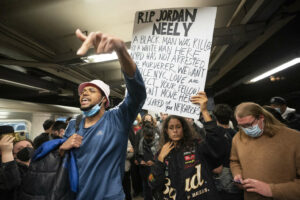

They seize on mass shootings, subway pushing incidents, and other horrific but extremely rare acts of violence committed by disabled people — who are far more likely to be at the receiving end of violence — to call for more force in the name of ‘treatment before tragedy.’ After the Sandy Hook shooting in 2013, former Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pennsylvania) led a multiyear legislative effort to scapegoat ‘mentally ill’ people for mass shootings and to expand involuntary and restrictive care federally. The bill never passed in Congress, but elements were folded into the 21st Century Cures Act.

Murphy was influenced by the work of E. Fuller Torrey, psychiatrist and founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC), a think tank advocating for involuntary outpatient commitment, euphemistically rebranded as Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT). Now on the books, in some form, in 47 states, these programs compel individuals to comply with court ordered ‘community treatment,’ under threat of inpatient commitment for noncompliance.

Brian Stettin, longtime policy director at TAC, helped to write the AOT laws in New York in 1999. In July 2022, he became the Adams administration’s senior adviser for severe mental illness, and authored the city’s psychiatric crisis care agenda, which heavily emphasizes the expanded use of AOT. Critics point out that AOT orders have been shown to be disproportionately enforced on Black and Brown people.

Today, we can be said to be living in a rising era of ‘carceral sanism.’ ‘Sanism’ is oppression faced due to the imperative to be ‘sane,’ ‘rational’ and non- ‘mad/crazy/mentally ill/psychiatrically disabled.’ In Decarcerating Disability, Liat defines carceral sanism as ‘forms of carcerality that contribute to the oppression of mad or “mentally ill” populations under the guise of treatment.'”

***

Back to Around the Web