Stopping psychiatric drugs is often difficult. And in many cases, it is done far too quickly. Therefore, the patient may develop unbearable withdrawal symptoms, which the doctor often interprets erroneously as a relapse of the disease.

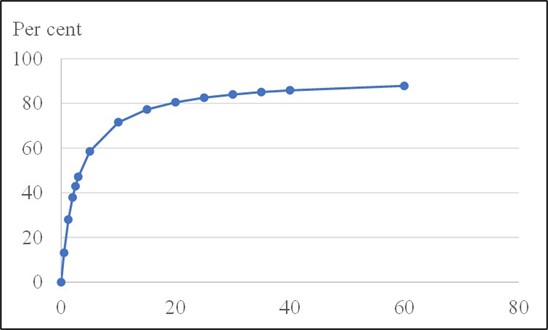

It is important to know how a tapering process should be carried out. Unfortunately, very few doctors know that the binding curves of psychiatric drugs to brain receptors are hyperbolic in shape. Here is one for citalopram, a depression drug:

To reduce the risk of withdrawal symptoms, it is necessary to respect the form of the binding curve. It is therefore clearly wrong to reduce the dose by halving it from step to step, which most doctors do.

When doctors halve the dose, it might go well the first time when the dose is halved from 100% to 50%. This is because the vast majority of patients are overdosed and are therefore still high up on the binding curve for psychiatric drugs when they come down to 50%. According to the FDA’s package insert, citalopram should be administered at an initial dose of 20 mg once daily, generally with an increase to a dose of 40 mg/day. Thus, by halving the dose from 40 mg to 20 mg, very little happens. In both cases, about 80% of the receptors are occupied.

But already the next time, when the patients go from 50% of the starting dose to 25%, it can go wrong. For example, in a patient who is on 20 mg/day of citalopram, a reduction from a full dose to a quarter of this dose means that receptor occupancy goes down from 80% to 60%. If there are no withdrawal symptoms this time, they will usually come when you take the next step and come down to 12.5% of the starting dose (corresponding to 40% receptor occupancy). It is also way too fast for many patients to change the dose every two weeks, which many guidelines recommend.

The physical dependence on the pills is often so pronounced that it takes many months, in some cases years, to fully recover from them. One of the worst withdrawal symptoms is extreme restlessness (akathisia), which predisposes to suicide and violence, and in rare cases homicide.

The shape of the binding curve is respected if a certain percentage of the previous dose is removed. If you start by removing 10% of the dose, you come down to 90% of the starting dose, and if you are down to 50%, you should not reduce to 25% but only to 45%. These principles have been known for decades and were meticulously described in 2019 by Horowitz and Taylor (the article is behind a paywall).

Psychiatric drugs are not sold in the low doses that are necessary for a successful withdrawal. But there are several methods one can use to produce low doses. On the frontpage of my website, Deadly Medicines & Organised Crime, there are links to instructions about how to do this. There is also a list of people who are willing to help patients withdraw, no matter where they live, because ongoing help can be provided via the Internet. Such help is strongly recommended. And there are “A practical guide to slow psychiatric drug withdrawal” and “Tips and tricks”, which is about producing small enough doses, e.g. by using a nail file and a scale for tablets, counting beads in certain types of capsules, or dissolving capsule content in water.

My book, Mental Health Survival Kit and Withdrawal from Psychiatric Drugs, describes this in detail. It is available for free in a serialised version on the Mad in America website and also available for free in Spanish, French and Portuguese on my website Institute for Scientific Freedom. In addition, it has been published in Danish, Dutch, Italian, and Swedish.

If you are a patient, then be prepared that many doctors say it is impossible to experience withdrawal symptoms when lowering a dose far below the smallest dose that is commercially available. This only demonstrates their ignorance about basic principles of clinical pharmacology.

Another method for acquiring very small doses is to use tapering strips, which doctors from any country can order from the Regenboog Apotheek in Amsterdam, a GMP-compliant compounding pharmacy.

On the website www.taperingstrip.com (available in multiple languages), everything is explained and standardised forms for individual drugs can be downloaded. The only thing the doctor needs to do is:

- Fill in the patient’s data (as for a regular prescription) and address for delivery

- Fill in the doctor’s own data (for verification that it’s a valid prescription)

- Fill in the start- and end-dose (enabling the pharmacy to make a leaflet with the daily doses)

Doctors who have doubts about how to fill in the form, or have other questions, are welcome to call Paul Harder at +31 625 072 020 or email [email protected].

The website was founded by Peter Groot and Jim van Os and the principle was developed by the User Research Centre of the Brain Department of the University Medical Centre of Utrecht.

The website informs doctors and patients about tapering the medication by gradually reducing the daily dose, thereby preventing or minimising withdrawal symptoms. Via the patients, the pharmacy receives useful feedback on how the tapering trajectory went, which can help improve the tapering schemes.

Several scientific studies have been published (freely available) based on information derived from the patients:

Groot PC, van Os J. Successful use of tapering strips for hyperbolic reduction of antidepressant dose – a cohort study. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2021; Aug 27.

Groot PC, van Os J. Outcome of Antidepressant Drug Discontinuation with Taperingstrips after 1-5 Years. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020;10:2045125320954609.

Groot PC, van Os J. Antidepressant tapering strips to help people come off medication more safely. Psychosis 2018;10:142-5.

van Os J, Groot PC. Outcomes of hyperbolic tapering of antidepressants. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2023; May 9;13:20451253231171518.

The website list of practitioners able to assist patients to withdraw from psychiatric meds is not current. Dr Charles Whitfield died in 2021.

Report comment

Having been led by my research to the work of the Orthomolecular Pioneers, Peter Breggin and Walther Bowman Russell, I attempted a number of times to withdraw from the Haldol/Lithium “cocktail” so popular with psychopharmacologists in the late 70s and early 80s.

Their instructions for taking a “drug holiday” were always the same: Taper down to a 2mg Haldol tablet and then stop. Experience eventually showed me that I could not quit 2mg per day “cold turkey”. I read up on titration and ground the Hadol tablet to a powder, eventually taking only a few grains of it every other day or so.

I stopped sleeping, but I felt good and lay in my bed all night listening to classical music on WCRB in Boston. After about two weeks, normal sleep patterns restarteded themselves. I knew I would never convinced that I needed to ingest those toxic products again.

The closer was my psychiatrist’s reaction to my success. He was furious that I had not followed his withdrawal protocol. Then he declared my remission “spontaneous”, leaving the door open for the “incurable brain disease, or suicidal ideation” to return. And he declined to make any more appointments with me or report my improvement to Veterans affairs. He then went on to be President of the APA and “write the book” (he had some help I guess) on psychopharmacology,

Report comment