Editor’s note from Robert Whitaker: We recently noticed on X/Twitter the posting of an article, published in Lancet Psychiatry, that was pitched as a review of the literature regarding the effectiveness of “alternative psychosocial interventions for people with acute, non-affective psychosis?”

The authors concluded that while there was abundant evidence from RCTs that antipsychotics are effective in treating “acute psychosis and reducing relapse,” and there was a much “smaller evidence base, of general low quality, in a few hundred people, for potential benefits of non-drug interventions.”

In particular, it derided the research that Jaakko Seikkula and colleagues have published on Open Dialogue outcomes, writing that: “Examining this literature, study design and reporting make it virtually impossible to comment on any benefits OD may confer. The design of studies would, at best, fulfill criteria for service evaluation, and there is evidence of allegiance bias, selection bias and reporting biases (selective reporting of outcome).”

I personally thought this article was a hatchet job, an article posing as an “objective” review of the evidence for “non-drug alternatives,” but done with the intent of reifying antipsychotics as the only “proven” treatment for psychosis, and dismissing research that told of positive outcomes for Open Dialogue and other such programs that embraced “selective use” of the drugs.

At that time, I didn’t notice that the article was two years old, and I wrote Jaakko Seikkula asking for a comment. He hadn’t seen the article, but once he had, he wrote a Letter to the Editor of Lancet Psychiatry. The editors rejected it, stating that such letters had to be written within four weeks of the print publication of the article.

Here is the letter that Jaakko Seikkula submitted to Lancet Psychiatry:

***

Commentary:

Use of neuroleptics in psychotic crisis is not an “either-or” question. Correcting the wrong statements of Jauhar and Lawrie about Open Dialogue studies

I read with an interest and curiosity the paper of Sameer Jauhar and Stephen M Lawrie titled “What is the evidence for antipsychotic medication and alternative psychosocial interventions for people with acute, non-affective psychosis?”

My curiosity turned into confusion about the purpose of this paper. It is presented as a critical analysis of studies that have provided support for alternatives to the use of neuroleptic medication for psychotic patients, but in fact it presents a prejudiced and selective review of the scientific literature.

The main part of the paper focused on RCT studies. However, placebo trials are reported to have many different types of problems affecting the reliability of the findings.1 As Taylor et al. note, “RCTs measure efficacy, but the controlled environment of a RCT affects the generalizability of the results in the ‘real world’, especially when high drop-out rates, short trial duration, and the selection bias in patient recruitment are considered. (…) The drop-out rates of even relatively brief RCTs in medication trials in psychiatry can be up to 70% or even 80%, confounding the applicability of the results. In addition, large multicentre RCTs are expensive to conduct, which militates against undertaking long-term or maintenance studies.”

In addition, the big problem with RCTs is that the efficacy found in such “laboratory” trials does not translate into the same efficacy in the real world. It is estimated that 20% of the reported efficacy is lost in everyday clinical practice.2 In addition, it is found that the efficacy of the trials has been exaggerated.3

The authors refer to studies about Open Dialogue in psychosis. It appears, however, that the authors did not read any articles published by the authors of the OD studies. None of the OD “findings” that the authors presented were true. How can Lancet approve papers without checking whether the information in the published paper is accurate? Should there not be a peer review process to guarantee that the arguments given are accurate and valid?

There are nine scientific papers about the outcomes in first episode non-affective psychosis in Open Dialogue care in Finnish Western Lapland. These studies are out of total three cohorts of research between 1992–2005. As an example, one of the papers4 is a quasi-experimental study among first-episode schizophrenia patients comparing two historical OD cohorts in Western Lapland with patients in another province in Finland. In the comparison group (N=14), all of the patients used neuroleptics, while in the OD groups (N=22/23) only 8 did. One significant element of OD is a selective use of neuroleptics based on the unique needs of every patient: some patients may never go on the drugs, some may use them for a time, and some may stay on them for a long time. The other core elements of Open Dialogue practice are to introduce early meetings in the crises, inviting the family and other relevant social network to active process of care, and in the therapy meetings focusing on generating dialogue to understand what has happened.

In the comparison group, at the two-year follow-up 50% had recovered from psychotic symptoms (7/14) while in the OD groups 63% and 82% (14/22 and 19/23) had recovered. Moreover, in the comparison group, only 6 of 14 had returned to full employment or active job-seeking, while 14/22 and 21/23 in the OD groups had. Among those recovered were all those patients who did not use neuroleptic medication.

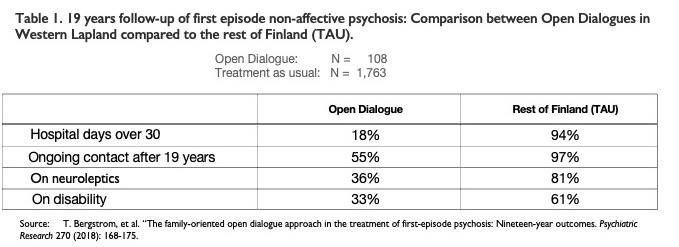

The differences in favor of OD were significant. In an observational study5 about 19-year follow-up comparing OD patients to “treatment as usual” (TAU) patients in Finland, this difference in outcomes persisted. The follow-up was based on data from the Finnish national registration of patients.

The statistics show significant differences in long-term outcomes. After 19 years, half of the patients in the TAU group were still in need of active care, compared to 28% of the OD patients. In the TAU group, 81% used neuroleptics compared to 36% in the OD patients. Sixty-one percent of the TAU group were on disability at the end of 19 years, compared to 33% in the OD group.

When studying6 the role of neuroleptic medication in the difference of outcomes, it was found that after adjustment for confounders, moderate and high cumulative exposure to antipsychotics within the first 5 years was consistently associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes during the 19-year follow-up, as compared to low or zero exposure.

We published studies on the outcomes in the three first-episode non-affective psychosis cohorts, and the outcomes were consistent across all three, confirming high external validity of the naturalistic design. Interventions studied in RCTs are typically much less effective once they are delivered in the real world. Since the Open Dialogue studies were already conducted in the real world, there is no such loss of efficacy. The external validity is higher in the naturalistic studies.

When we assess the use of neuroleptics as a treatment for psychosis, it is essential to conduct research in a real-world setting, because that is the only way we can find the real impact of their use. And in the real world, it is not a question of either using the medications or not using them, but rather of creating a process that enables us to select those who can benefit from the drugs, those who do not need them, and perhaps most important, those for whom neuroleptics are harmful. Open Dialogue practice is an example of how such real-world care can lead to much improved long-term outcomes.

The article by Jauhar and Lawrie dismissed OD without reviewing the study results that have been published, and most important, without referencing the 19-year results that showed much superior outcomes for those treated with OD compared to TAU. To dismiss OD without reviewing the study results does a disservice to your readers.

Given the fact that the antipsychotics / neuroleptics can create the positive symptoms of ‘schizophrenia,’ via anticholinergic toxidrome. And they can also create the negative symptoms of ‘schizophrenia,’ via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

The antipsychotics / neuroleptics should NOT be a first line of treatment for all in emergency rooms.

But, since I recently had a, relatively good, experience with emergency services and hospitals with a loved one. I do have a recommendation for an alternative, for those who are manic and psychotic.

Now I say ‘relatively good,’ since it did result in three hospitalizations, which is not good. A little background, my loved one had been abruptly taken off two heart meds, since they were known to cause kidney failure, so they should not have been prescribed to my loved one together in the first place.

Nonetheless, at my loved one’s first hospitalization, I was able to prevent him from being put on an antipsychotic. He was calmed down with a benzo instead, which did not work. The second time he was hospitalized, I was not able to prevent him from being put on an antipsychotic, abrupt drug withdrawal from which caused a very severe super sensitivity manic psychosis.

I was able to prevent him from being given anticholinergic drugs at his third hospitalization, but he was psych hospitalized. He was given a low dose of lithium (600mg/day) only. He complained because he was kept in the psych ward for over a week, while most were let out within days, on antipsychotics.

However, the low dose of lithium did work to calm down my “non-violent” loved one. It has been about four months since he was let out. He’s now off the lithium, may be slightly manic, but in a good way (he’s actually cleaning his home). But … so far, so good.

I’m sure OD would likely have been helpful too, but they don’t have OD programs near me.

Report comment

Yes these toxic powerful compounds are quite effective like a sledgehammer can demolish a nail into a plank- taking good care of both the nail and that piece of wood for good. On shot!

Report comment

Is the evidence strong enough to support medicating of nearly all with antipsychotics long-term?

I would like to comment “antipsychotics are effective in treating acute psychosis and reducing relapse” on the background of how many are medicated and how long. Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health found excessive medication and World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) suggest how to solve these problems. The solution seems to be a shift of paradigm and revolution to obtain recovery (9).

Nearly all randomized controlled trials (RCT) use a “wash-out” period before randomizing to

placebo or drug because it was considered unethical not to give antipsychotics. Both Carpender and Bola 2011 found that studies with antipsychotics-naive participants are safe and therefore not unethical.

Leucht et al. found in 2017 that 14% placebo respons for acute good symptom reduction, and 9% benefit i. e. 91% had no benefit of drugs.

Dalbø et al. (Norwegian Institute of Public Health) (1) concluded 2019: “ It is uncertain if antipsychotics compared to placebo affects symptoms in persons with early psychosis” because antipsychotic-naive participants are missing.

Iversen et al.(2) found 2018 in “Side effect burden of antipsychotic drugs in real life – Impact of gender and polypharmacy”: Use of antipsychotics showed significant associations to neurologic and sexual symptoms, sedation, and weight gain, and >75% of antipsychotics-users reported side effects.

Lindstrøm et al. (3) reports 2001 total of 94% of side effects for patients under maintenance treatment.

Danborg et al.(4) conclude that: “The use of antipsychotics cannot be justified based on the evidence we currently have. Withdrawal effects in the placebo groups make existing placebo-controlled trials unreliable.”

The strict claim of antipsychotic-naive research leaves the medication of nearly all patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia without justification and, therefore, maintenance results without relevance because of possible withdrawal effects.

According to Leucht et al. 2012 “nothing is known about the long-term effects of antipsychotic drugs compared to placebo. Future studies should focus on the,outcomes of social participation and clarify the long-term morbidity and mortality associated with these drugs.” The study was based on 7 to 12 month.

Schlier et al. 2023 (5) conducted the first meta-analysis pooling the long-term effects of antipsychotic maintenance versus discontinuation on functional recovery in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The result was that the benefit of maintenance disappears after two years. The clinical experience that the disease returns on discontinuation is an illusion as abstinence is ignored.

Sohler et al. 2015 (6) found in “Weighing the Evidence for Harm from Long-term Treatment with

Antipsychotic Medications, A Systematic Review” no evidence for long term treatment: “We believe the pervasive acceptance of this treatment modality has hindered rigorous scientific inquiry that is necessary to ensure evidence-based psychiatric care is being offered.”

This evidence for medicating nearly all is already very weak, but there is no evidence at all for long-term medication.

UN Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health, WHO and UN

United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health Mr. Puras has called for «World needs “revolution” in mental health care» due to “unequivocal evidence of the failures of a system that relies too heavily on the biomedical model of mental health services, including the front-line and excessive use of psychotropic medicines, and yet these models persist” (7).

WHO (60) followed up with the “(n)ew WHO guidance (which) seeks to put an end to human rights violations in mental health care”: “This comprehensive new guidance provides a strong argument for a much faster transition from mental health services that use coercion and focus almost exclusively on the use of medication to manage symptoms of mental health conditions, to a more holistic approach that takes into account the specific circumstances and wishes of the individual and offers a variety of approaches for treatment and support”. Compulsory Community Treatment Orders and forced injections of antipsychotics are ineffective and unethical.

The WHO-OHCHR guidance launched October 2023 seeks to improve laws addressing human rights abuses in mental health care (WHO-OHCHR 2023 (8) ) to support countries in reforming legislation in order to end human rights abuses and increase access to quality mental health care.

Treatment-As-Usual (TAU) did not improve patients recovery, mainly due to resistance to giving up excessive medication. Legislators can solve this deadlock by following OHCHR suggestions and removing legal permission for forced drugging. This could promote a shift of paradigm of treatment of schizophrenia towards recovery (9).

References:

1. Dalsbø TK, Dahm, KT, Øvernes, LA, Lauritzen M, Skjelbakken T. [Effectiveness of treatment for psychosis: evidence base for a shared decision-making tool] Rapport 2019. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet, [Norwegian Institute of Public Health ]

2019.

2. Iversen TSJ, Steen NE, Dieset I, et al. Side effect burden of antipsychotic drugs in real life – Impact of gender and

polypharmacy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;82:263-271. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.004 Nov 7.

PMID: 29122637.

3. Lindström E, Lewander T, Malm U, Malt UF, Lublin H, Ahlfors UG. Patient-rated versus clinician-rated side effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia. Clinical validation of a self-rating version of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU-SERS-Pat). Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55 Suppl 44:5-69. doi:10.1080/080394801317084428

4. Danborg PB, Gøtzsche PC. Benefits and harms of antipsychotic drugs in drug-naïve patients with psychosis: A systematic review. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2019;30(4):193-201. doi:10.3233/JRS-195063

5. Schlier et al. 2023. Time-dependent effect of antipsychotic discontinuation and dose reduction on social functioning and subjective quality of life–a multilevel meta-analysis. EeClinicMedicine Volume 65, 102291, November 2023. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102291

6.. Sohler N, Adams BG, Barnes DM, Cohen GH, Prins SJ, Schwartz S. Weighing the evidence for harm from long-term treatment with antipsychotic medications: A systematic review. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86(5):477-485.doi:10.1037/ort0000106

7. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Dainius Puras “World needs “revolution” in mental health care – UN rights expert” online publication 06 June 2017. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2017/06/world-needs-revolution-mental-health-care-un-rights-expert?LangID=E

8. WHO “New WHO guidance seeks to put an end to human rights violations in mental health care” online publication 10 June 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/10-06-2021-new-who-guidance-seeks-to-put-an-end-to-human-rights-violations-in-mental-health-care

9. Keim, Walter. Paradigm Shift to Promote a Revolution of Treatment of Schizophrenia to Achieve Recovery. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 11, n. 12, dec. 2023. ISSN 2375-1924. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v11i12.4866

Report comment

Lancet Psychiatry have, by refusing to publish this, declared an open hostility to at least Open Dialogue, if not all alternative treatments, for so-called schizophrenia. There would be immense global interest in a debate between Jaakko and TAU psychiatry. Lancet could have published this letter with a note attached as to the delay between Jauher and Lawrie’s paper and Jaakko’s response. It must have occurred to the editors of Lancet there would have been immense international interest and contact Jaakko for his reaction? What’s their responsibility? Do you know whether any other journals have contacted both Jaakko and Jauher & Lowrie to continue the debate in their pages. It would certainly boost readership (and rankings) amongst some lower-ranked journal – what an opportunity.

Just what is Lancet Psychiatry’s fear? Psychiatry came into existence mid-nineteenth century because the courts recognised their moral authority and granted them the power to incarcerate citizens. They made various claims about their ability to predict dangerousness. Is that the fear which drives psychiatry – that they will be exposed as charlatans and at that point their moral authority is considerably diminished – and the courts will be overwhelmed with people saying they have been wrongfully detained – and that is a scenario thats far scarier to contemplate?

Thanks Jaakko and Robert for bringing this to our attention.

Report comment