Editor’s note: This article by Gaurav Datta was first published on Mad in South Asia.

Some of the most marginalized and stigmatized people in a community are those with psychiatric diagnoses and those who are HIV positive. What remains common about these two groups are how they are portrayed through a “humanitarian gaze” as helpless, burdensome, and unable to contribute meaningfully—their lives are often reduced to how much they cost (Global Burden of Disease). In this piece, Gaurav Datta takes us through a pictorial journey of the lives of some of these people at Philip AIDS Center. Among death, despair, dehumanization, and drugs (antipsychotics), Datta challenges our ideas of humanitarian care and biomedicalization in showing how residents take care of each other.

NIGHT

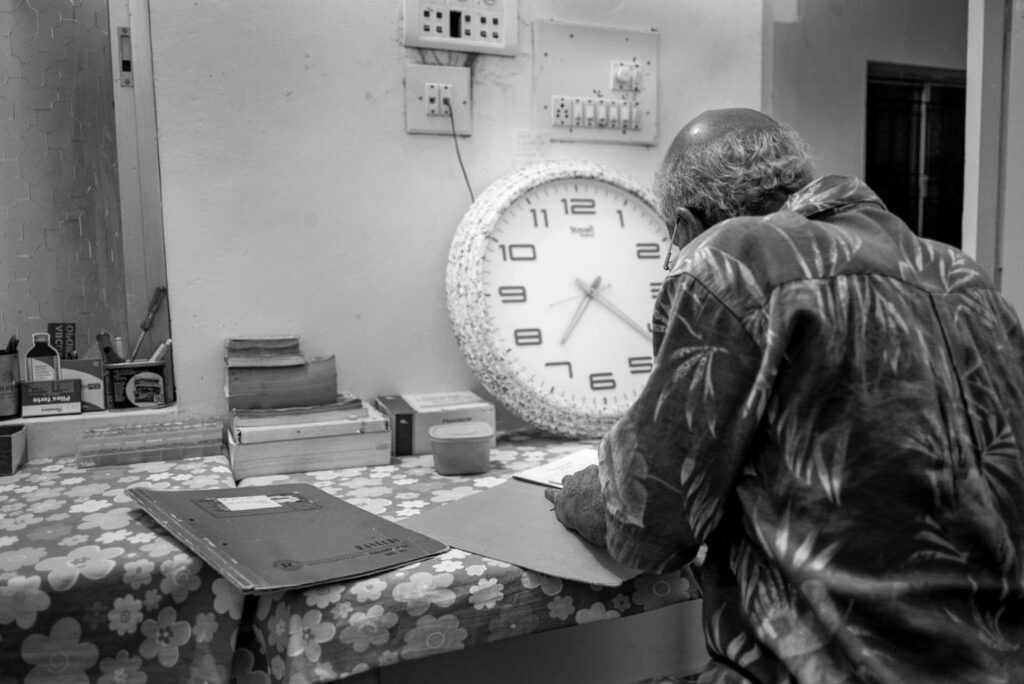

When the Sisters called Father Paul to the patient ward that night, he asked me to come along but did not reveal why. Ajay was at the door as usual, but this time he did not greet Father Paul with his daily question “maut kab aayega?” (when will death come?). Father Paul followed his routine of visiting the patients in a sequential manner, first the balcony, then to the TV room, the dining room, the male ward, and finally to the female ward where Jaya ben was. Two of the Sisters had gathered around Jaya ben, trying to feed her a mix of dal and rice from a steel plate with raised rim. Jaya ben just sat there on a chair, probably too tired to swallow, and also too tired to resist. A senior Sister came into the room with a bag full of chikoos, and cheerfully announced “These are so sweet, perfectly ripe! We will have a fruit salad party tomorrow.” Maybe Jaya ben would enjoy the chikoo more, I thought. Someone remembered that there were grapes as well and went off to get them. Another Sister went to find a bowl to mash the chikoos and grapes for her. Father Paul went around the room, touching the foreheads of the other residents until he reached Jaya ben. He spoke to her, chiding her playfully to eat. Jaya ben’s face did not light up on seeing him this time as it usually did, but had a look of extreme tiredness and exasperation, almost begging to be freed from this ordeal. He took her pulse, blessed her on the forehead, and asked me to follow him to the ‘medicine’ room. I was hesitant, but complied anyway.

THE NEXT DAY

Father Paul was supposed to leave for another city, so we had an early breakfast at 6:15 am. Everyone was worried about Jaya ben. She had been having epileptic fits for a few days, and had cut her forehead having fallen down from the bed. The Sisters and other residents had then made a bed for her on the floor, and were now debating whether to get her admitted to a neurology ward in the hospital instead of a taking her to a psychiatrist. Jaya ben had been diagnosed with ‘psychosis unspecified’ along with HIV, and has been on different anti-psychotics and sleeping aids for more than 5 years. “Admitting a female patient would require someone to stay with her. With Father Paul gone for a few days and one Sister with Jaya ben, how can the two of us look after all the residents?” one Sister sighed. “She hasn’t been eating much lately, and is getting weaker and weaker” I said. “Let’s see for some time, I will return if there’s an emergency” said Father Paul. Afterwards, at prayer following the sermon, Father Paul asked us to pray for Rajesh—another resident’s speedy recovery who was supposed to go into surgery today for a small tumor that had been delayed for quite a while. “And our beloved Jaya ben, may she recover quickly as well.” We all prayed.

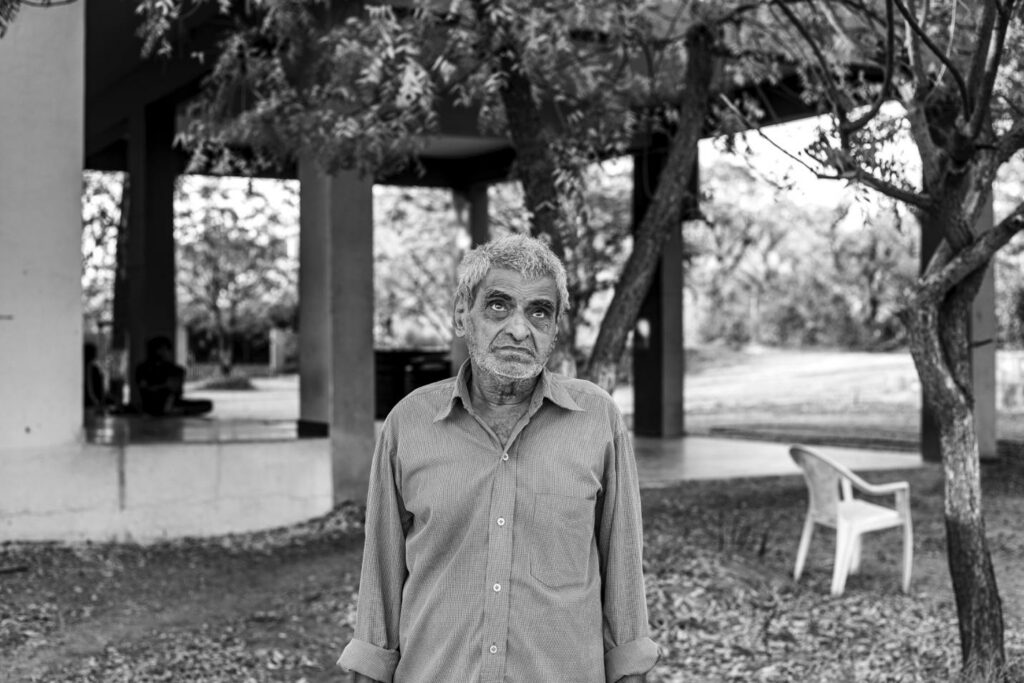

The Socially Abandoned People Of Philip AIDS Centre Living With HIV/AIDS

To imagine the landscape not as a passive entity, but as a silent witness to their struggles and resistance.

To imagine these people as having traversed these landscapes losing all their belongings and sense of self.

To whom do we attribute the ability to care?

To what extent do we challenge our own assumptions on care and the ‘Humanitarian gaze’?

Susan Sontag writes in Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors that “Where once it was the physician who waged bellum contra morbum, the war against disease, now it’s the whole society”, and this war has now extended to the ‘diseased’ as well. She further goes on to add that “Military metaphors contribute to the stigmatizing of certain illnesses and, by extension, of those who are ill”, and that “the most terrifying illnesses are those perceived not just as lethal but as dehumanizing, literally so”. Now, as antiretroviral therapy (ART) becomes more accessible and people with HIV live longer, it is important to remember that palliative care also constitutes an important aspect of HIV care (Harding, 2018), and it is this form of interpersonal care among the residents that I attend to in this essay.

Recognizing that the media’s depiction of HIV/AIDS has primarily been one of “death voyeurism”, which has strongly shaped the view that people with HIV/AIDS and psychiatric disorders need to be cared for by ‘us’ (Campbell, 2008), and that ‘they’ are incapable of caring for others and which continues to be perpetuated in global health (Charani et al., 2022), I wanted to shift away from the ‘humanitarian gaze’ and use these photographs both as a way to depict and challenge existing notions of care. Thus, to recognize the act of caring itself as resistance, resistance to the biomedicalization and dehumanization of their illness experience, and as acts of solidarity and survival in this world (Cook, Trundle, 2020).

It could be tempting to dismiss the role of role of medicines in the lives of these people: Father Paul established this Centre in the memory of his nephew Philips whom he lost to HIV/AIDS at a time when antiretrovirals were not easily available, the residents know very well that the antiretrovirals are what keeps them alive. It could also be tempting to undervalue the biomedical care as provided by the Sisters and think of it as ‘pharmaceutical domestication’, or to overstate the role of spirituality and prayers. To instead, recognize that the various forms of care as co-existing with each other, often unsettling and defying strict categorization.

Notes On The Photographs

All photographs were taken between 2015-2022, combining the methods of participant observation, volunteering, visual ethnography and photo-elicitation. The names of residents have been changed to protect their identity, and all the residents photographed gave their informed consent to have the above photographs published. For the residents who were unable to provide consent, they were either not photographed, or photographed in a way to not reveal their faces.

References

- Campbell, David. The Visual Economy of AIDS, 2008. https://www.david-campbell.org/photography/hivaids

- Charani, Esmita et al. (2022), The use of imagery in global health: an analysis of infectious disease documents and a framework to guide practice. The Lancet Global Health, Volume 11, Issue 1, e155 – e164

- Cook, J. and Trundle, C. (2020), Unsettled Care: Temporality, Subjectivity, and the Uneasy Ethics of Care. Anthropology and Humanism, 45: 178-183. https://doi.org/10.1111/anhu.12308.

- Harding, R. (2018). Palliative care as an essential component of the HIV care continuum, Lancet HIV 2018; 5: e524-530.

- Sontag, Susan (1989). Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. Penguin Classics.