While conducting research in rural Northern India, Ayurdhi Dhar spoke to a woman whose mother had vivid visual hallucinations of Indian wedding processions. When Dhar asked how this woman’s mother coped with her hallucinations, the woman said nothing about medication or therapy. Instead, she replied, “What do you do when there’s music? You dance!”

Through conversations like this, Dhar discovered that “what we call hallucinatory phenomena was really common and not always pathological, or even problematic” for her project’s participants. Unfortunately, though, biomedical views of mental health, which say hallucinations and other mental symptoms must be addressed medically, are increasingly prevalent in India and other South Asian countries. According to Dhar, this biomedical influence is dangerous not only because it limits possibilities for healing, as it would in any region, but also because it lacks relevance to South Asians in particular. “I was looking at the global mental health movement coming in and erasing these diverse ways of being human,” Dhar explains.

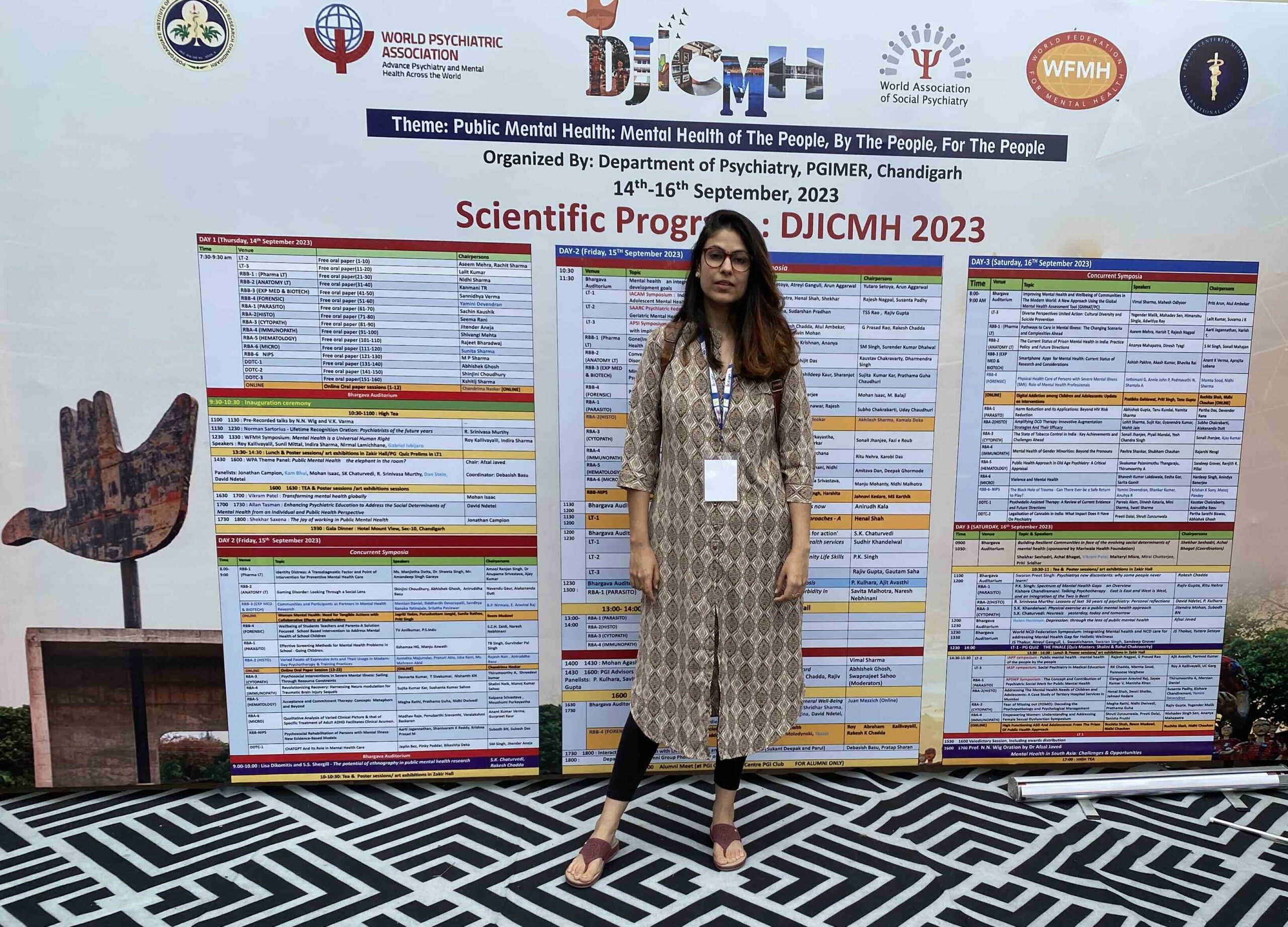

This issue is exactly what Dhar aims to address through Mad in South Asia (MISA). She was already involved with Mad in America before founding the affiliate site—she became a science writer, and later a spotlight interview host, after connecting with MIA’s science news editor at a conference while doing her PhD at the University of West Georgia. When Dhar later moved back to India, she saw this as the perfect time to start an affiliate site centering experiences unique to South Asia.

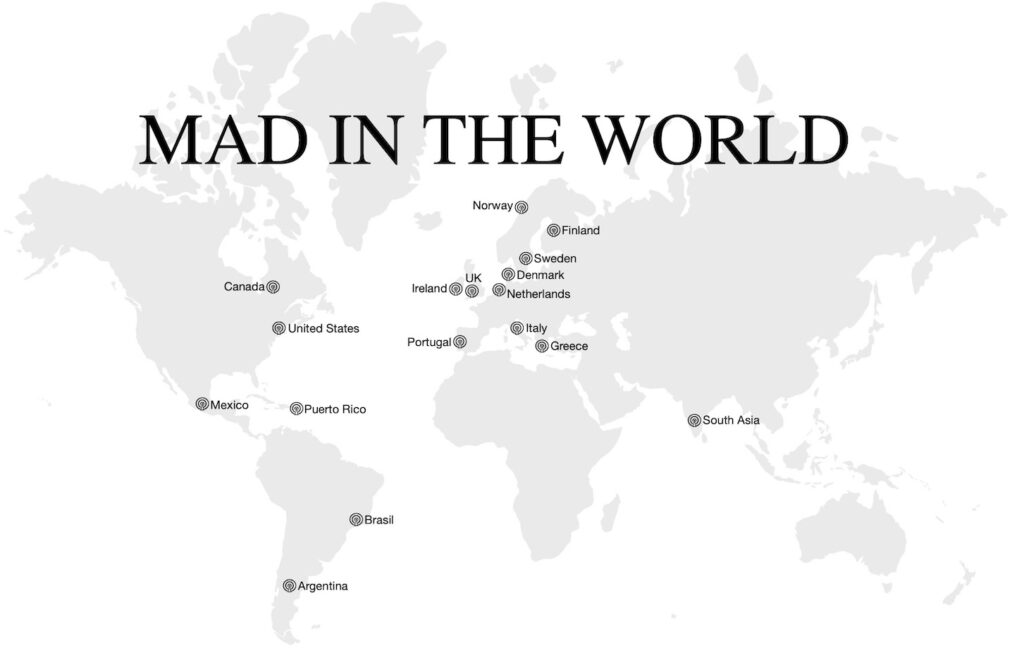

Instead of focusing solely on India, Dhar chose to include other South Asian countries—Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Bhutan, and Nepal—because of the similar cultures and subjectivities they all share. As stated on MISA’s “About” page, this was an opportunity to collectively put forth “a psychology that is created by us, for us,” pushing back against Western-dominated views of psychology.

For example, Dhar criticizes the “internal paranoia of the other” that’s popular in the West. “There’s a romanticization of boundaries, cutting off the toxic people in your life,” she says. “But when your sense of self is built through other people, cutting them off is not that easy… In a place like India, it’s very common to just keep people you hate close to you.”

Dhar hoped MISA could help counteract the influence of the South Asian diaspora in the US—who, as she puts it, have “no idea what it’s like to live in South Asia.” She adds, “They think that just because some things are true for them, [they’re] true for all South Asians.”

This population often ends up pathologizing situations that are normal in South Asian culture, such as family members making decisions for one another. “In most of the world, you make decisions for others, they make decisions for you,” notes Dhar. “Sure, it can be problematic if you live in a culture that doesn’t do that… but not in places where that’s just common.”

Back in India, Dhar got to work putting together a team for MISA—but finding others whose views aligned with MISA’s alternative standpoint proved difficult. “It’s very rare to find people with a critical edge,” Dhar says. Because of this, she doesn’t like to call MISA a “mental health thing,” since this term tends to draw in people with a more conventional outlook on emotional distress.

In the end, Dhar turned to her existing connections, including current team member Sugandh Dixit, as well as Kimberly Lacroix, who Dixit knew from their shared work in community mental health. Together, the group built a website with pages for research news, expert opinions, personal stories, podcasts and interviews, and resources. The site also includes pages for two of South Asia’s East Asian neighbors, China and Vietnam.

The group focuses on South Asia-based research studies and perspectives in order to promote South Asian viewpoints that differ from Western ones. For example, Dhar notes that doctors in India must prescribe medications chosen by the government, reducing the sway pharmaceutical companies have over their thinking. Because of this, they’re often aware of problems in the psychiatric field that clinicians in Western countries remain blind to. “I have never in my time in the US heard psychiatrists say diagnosis doesn’t have an objective entity,” Dhar explains—but in India, doctors have said this to her outright.

“These guys [have] deep sensitivity to context,” she says. “But that’s dying.”

As the biomedical model strengthens its grip in South Asia, Dhar finds herself particularly worried about those in rural areas, where NGOs have begun sending in community health workers (CHWs) as part of global mental health campaigns, which often do more harm than good. “Farmers in India are killing themselves,” says Dhar. “These CHWs go and say, hey, it’s just a chemical imbalance, because I have information that you don’t. So take an antidepressant.”

Dhar adds that South Asian culture’s “reverence” for medicine makes this phenomenon especially dangerous. “[South Asians] will listen to the doctor,” she says. “He’s treated like God. So if they’re told that you take this pill, they will take it.”

Another objective of MISA, then, is to fight against this by featuring alternative approaches still present in South Asia. Recently, for example, MISA sent reporter Rohini Roy to a number of faith healing sites, which exist around the world but are especially prominent in South Asia. This project culminated in a four-part series of reports sharing the stories of these sites’ visitors—many of whom arrived after first trying psychiatric treatments that proved unhelpful.

Dhar explains that the rise of the biomedical model has created a “witch hunt” against these sites, and many have already been shut down or seriously restricted in their practices. While it’s true that abuse has happened at some sites, Roy and Dhar both argue that this is a reason to regulate faith healing sites, not to shut them down. “Anytime you have somebody with a position of power, they can abuse people and exploit them,” Dhar notes—the same being true for psychiatric hospitals, which Dhar also hopes to publish a report on in the future.

“I want MISA to eventually be able to represent the multiple ways people take care of themselves and each other in different places,” Dhar says. This opportunity to learn from others’ experiences is something she appreciates about the Mad in the World network—particularly because her interest in mental health is primarily academic rather than based in personal experience. Dhar says that the stories of those who run other affiliate sites help her stay motivated to continue her work at MISA by reminding her of its importance. “The harm is so, so real,” Dhar says. “You can forget sometimes that there are people under it. Real people with real horror stories.”

Moving forward, Dhar hopes to expand MISA’s geographic reach, since the current team is “pretty India heavy.” “We’re really trying to get people from other parts of South Asia,” she said. “I just keep asking people, if they know someone in Sri Lanka or Bangladesh or Nepal, to let us know.”

She also expresses concerns about the challenges MISA may face as it continues to evolve. For one, she mentions that journalists in India have to be careful not to say anything that could be construed as anti-national, which can make it hard to openly discuss problems causing mental suffering in India today.

In addition, Dhar believes backlash against MISA’s alternative outlook may increase as the website’s reach expands. While responses from readers have so far been overwhelmingly positive, those from experts are more mixed. Dhar explains that people from fields like public policy, anthropology, social work, and public health generally seem to connect with MISA’s approach, but that psychologists sometimes have a “raging reaction,” like one woman who recently approached Dhar at a conference.

“She cried,” Dhar recalls. “She was so mad about the things that I had said. She wanted to punch me, but thankfully she did not.”

Still, Dhar refuses to give in to MISA’s critics. As she puts it, “If you don’t piss some people off, then what are you doing?”

Good article. As she puts it, “If you don’t piss some people off, then what are you doing?” Go Dhar!

Report comment