When Laura Lopez-Aybar was thirteen, she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder (BPD). According to her clinicians, these were serious illnesses that would alter the course of her future, requiring her to take medication indefinitely because she would never be able to regulate her emotions on her own.

Throughout her teenage years, everything Lopez-Aybar did was treated as a sign of her mental illness. When she started experimenting sexually as a teenager, this was apparently a consequence of her BPD. When she danced alone in her bedroom to let off steam, this was a sign of a manic phase. “I was getting medicated, locked up, and basically incarcerated both in my house and in psychiatric institutions,” she says. Yet when she showed distress about these abuses, this too was apparently just further evidence of her inability to cope. “I was destined to live under my mother’s roof for the rest of my life,” she recalls.

But as she got older, Lopez-Aybar recognized flaws in the stories she’d been told about herself—and she started to question the value of the therapies she’d been prescribed. What would the positive affirmations her therapists taught her ever do to combat the abuse she was facing? What good was medication if all it did was transform her from a high achiever with an off-the-charts IQ score to a student too sedated to manage her hygiene, let alone stay alert during classes?

But as she got older, Lopez-Aybar recognized flaws in the stories she’d been told about herself—and she started to question the value of the therapies she’d been prescribed. What would the positive affirmations her therapists taught her ever do to combat the abuse she was facing? What good was medication if all it did was transform her from a high achiever with an off-the-charts IQ score to a student too sedated to manage her hygiene, let alone stay alert during classes?

These early experiences inspired Lopez-Aybar to get her PhD in clinical psychology and focus her research on psychiatric violence and social determinants of health. “I wanted to, and I still want, delusionally, to change the field and the world of psychiatry,” she explains.

Her clinical training only reinforced her existing concerns. “I worked in carceral settings throughout my entire training,” she says. Once, during a particularly distressing clinical internship, she reached out to colleague Jose Luiggi-Hernandez for support and, learning that he was a science writer for Mad in America, discovered that they shared many of the same views.

Growing up in a highly religious household, Luiggi-Hernandez was always taught to see his problems as his own fault, issues he could only resolve through his relationship to God. “I thought there was something inherently wrong with that,” he says, “but I didn’t have the words or the material to make sense of what my own thoughts were.”

This was until, in college at the University of Puerto Rico, he was assigned readings by Freud and Marx that argued that larger societal forces, rather than individual faults, were the sources of psychological distress. “Suddenly, I had this new vision of why we suffer,” says Luiggi-Hernandez. “We don’t suffer because we have a personality that’s broken. There’s not something wrong with our brain.” Rather, he realized, mental distress was “embedded within our larger social, cultural life.”

Luiggi-Hernandez’s studies also exposed him to the problems with psychiatric institutions themselves. “I always thought there was a possibility of doing something different,” he says, and getting involved with Mad in America confirmed these suspicions. Now, Luiggi-Hernandez is a professor and clinician, with his work centering on critical and decolonial psychology.

As Lopez-Aybar and Luiggi-Hernandez talked further, they concluded that Puerto Rico needed its own Mad in the World affiliate. While Puerto Rico is officially a territory of the United States, Luiggi-Hernandez explains, “The only thing that’s actually American about Puerto Rico is the legal aspect.”

Because of this, he says, “A lot of people here wouldn’t be able to read Mad in America articles,” not only because their first language is Spanish rather than English, but also because the challenges Puerto Ricans deal with have little overlap with those faced by Americans. In particular, since Puerto Rico is, in essence, a colony of the United States, colonialism has a heavy impact on both Puerto Ricans’ mental health and the ways their distress is addressed by the health system.

“It’s been pretty colonized into the minds of the people here that the only approach and the best approach is the biomedical approach,” says Lopez-Aybar.

The US, she explains, has at least some diversity of thought when it comes to mental health, but Puerto Rican psychiatry tends to “double down on oppression,” not only denouncing non-Christian modes of healing, which are widespread on an island as culturally diverse in Puerto Rico, but actually viewing them as satanic. In addition, Luiggi-Hernandez says, Puerto Rican psychiatrists often feel pressure to not only imitate their American counterparts but to actually outdo them, acting “almost like a cartoon version of what they think American psychology and psychiatry is like.”

“Right now, the discourse is very much like, Medicate yourself, you have to use medication,” says Lopez-Aybar. “Everyone’s diagnosing themselves with a thousand diseases.” What people aren’t talking about are the broader political and economic circumstances that influence mental health, including everything from poverty and gentrification to the environmental impact of climate change. “As a mental health provider,” Lopez-Aybar explains, “you have to be neutral. You can’t have any political opinions… Activism is kind of demonized in the mental health field.”

This puts a damper on any possibility of meaningful systemic change. “There’s no dialogue around alternatives to mental health,” says Lopez-Aybar. Certain “islands of people” are working to address this, but because they’re all detached from each other, it’s difficult to band together and make a real difference. It doesn’t help that Puerto Rico lacks political sovereignty. “Our resources are being taken away from us,” says Luiggi-Hernandez. This economic strain only makes it harder to implement alternatives.

On Mad in Puerto Rico’s site, Lopez-Aybar and Luiggi-Hernandez publish interviews, testimonies from psychiatric survivors, research and editorial news, and informational resources about topics like withdrawal symptoms. Through this, they aim to highlight the alternative approaches that are currently overlooked in Puerto Rico, connecting these with decolonial activism.

So far, the response to Mad in Puerto has been mostly positive. People often reach out to thank the team or ask for advice about finding support services they can trust, although this can be tricky to respond to when so few alternatives exist to recommend. Meanwhile, some psychologists have offered positive feedback or even mentioned that they used Mad in Puerto Rico’s content in their actual training activities.

At the same time, Lopez-Ayber says, using “more radical terms” can lead to backlash. For example, she posted a video about the term “psychiatric survivor” and received responses from people arguing that their own experiences with psychiatric treatment were beneficial. Similarly, psychologists sometimes claim that Mad in Puerto is creating stigma, even going as far as to suggest that the violent abuses called out by the site aren’t real. “It feels, sometimes, pretty personal,” says Lopez-Aybar. After all, these abuses often resemble her own experiences.

In addition, the team sometimes struggles because Mad in Puerto is still a “super passion project,” as Lopez-Aybar puts it, which means they’re not only balancing it with their full-time careers but also paying for parts of it out of their own pockets. While the team has experience obtaining funding for research, securing more funding for Mad in Puerto Rico would involve an entirely different process that neither team member is familiar with. Donations, meanwhile, are hard to acquire because, Lopez-Aybar explains, “People here are fighting for their lives. Spending money is a commodity.”

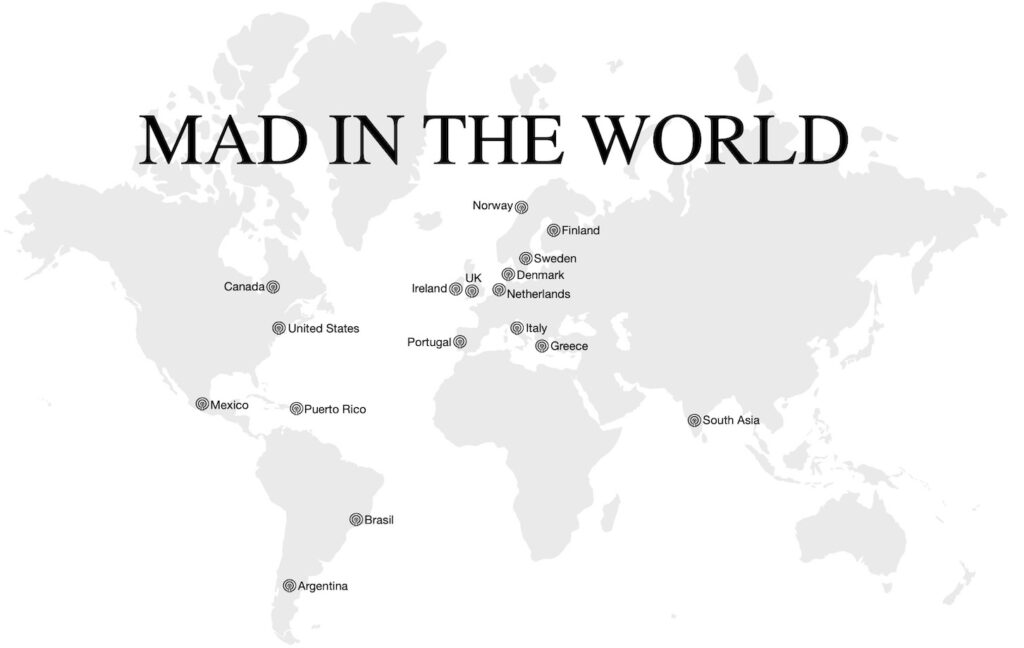

Even so, the team is constantly thinking of projects Mad in Puerto Rico could take on next: a photo book of psychiatric survivors, a list of resources for accessing support, collaborations with other Mad in the World sites. They also hope to expand beyond the site itself, hosting poetry readings and film showings with creators whose work aligns with their mission or providing trainings for providers on topics like the Power Threat Meaning Framework, an alternative to the DSM. “I have a whole world of ideas,” says Lopez-Aybar.

Well this is great to see and your home is still not well represented in our country not a state and your history is vast and deep. I think of Lin Manuel Miranda and his song Puerto Rico and I hope the money did get there for aid and support.

I would love to know more about the histiry in all systems and this for all the other sites. I would line some Histiry and cultural heritage lessons and fun and enjoyable along with the sorrow and tragedies. Thanks for your efforts.

Report comment

Bravo

Report comment