On June 18, the British Medical Journal published an article by Christine Lu, et al., titled Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study.

Here’s the conclusion paragraph from the abstract:

“Safety warnings about antidepressants and widespread media coverage decreased antidepressant use, and there were simultaneous increases in suicide attempts among young people. It is essential to monitor and reduce possible unintended consequences of FDA warnings and media reporting.”

Note the slightly rebuking tone directed against the FDA and the media.

Source of Data

The researchers interrogated the claims databases (2000-2010) of eleven medical insurance groups who collectively cover about 10 million people in 12 geographically scattered US locations. All groups were members of the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN).

The general concept behind this sort of research network is that computerized insurance claims data represent an enormous repository of potentially very useful information, which researchers can readily tap for answers to questions that are difficult to resolve with smaller-scale data. MHRN’s website, under the tab “Funding,” states:

“Initial funding for the MHRN is through a 3-year cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Mental Health (U19 MH092201 “Mental Health Research Network: A Population-Based Approach to Transform Research”) and through a supplement from NIMH to the existing Cancer Research Network funded by the National Cancer Institute.

During the initial funding cycle, the MHRN developed core infrastructure for collaborative research and conducted four developmental research projects to test and leverage that infrastructure in specific clinical areas.”

The Lu, et al., study is one of these four projects.

MHRN’s “virtual data warehouse” contains information on inpatient and outpatient treatment, and outpatient pharmacy data. It also contains, for deceased members, the date and cause of death.

The present study included all adolescents (10-17), young adults (18-24), and adults (20-64) in the eleven insurance groups.

Variables Studied

From the pharmacy data, the authors calculated the quarterly percentages of individuals who were dispensed an antidepressant.

The frequency of suicide attempts was measured by the quarterly incidence of “poisoning by psychotropic agents,” (ICD-9 code 969), that resulted in inpatient or ER treatment.

The frequency of completed suicides per 100,000 members was also calculated quarterly. Although the other data elements are presented for each quarter up to the end of 2010, the completed suicide data stops at the end of 2008. The authors explain: “There is generally a lag time of 12-24 months for both reporting of deaths and availability of data; therefore we analyzed data on deaths up to and including 2008.”

Time Frame

The study’s time frame was from the first quarter of 2000 to the last quarter of 2010. The researchers divided this time frame into three segments:

1. The pre-warning phase (2000, q1 – 2003, q3)

2. The phase-in period (2003, q4 – 2004, q4)

3. The post-warning period (2005, q1 – 2010, q4)

The FDA black box warnings were mandated in October 2004.

The authors justify the use of a phase-in period as follows:

“To deal with the possibility of an anticipatory response to the warnings, we considered the last quarter of 2003 to the last quarter of 2004 as a ‘phase-in’ period that spanned the entire period of FDA advisories, the boxed warning, and intense media coverage, and excluded these five data points from the regression models.”

Regression, in this context, basically means finding a line-of-best-fit through a series of points which represent data on a graph.

Results

The study included approximately the following numbers of individuals:

Adolescents (10-17) 1.1 million

Young adults (18-29) 1.4 million

Adults (30-64) 5 million

The results for the three age groups are set out in graph form and are designated Figures 1, 2, and 3.

Let’s start with the adolescent graphs (Fig 1)

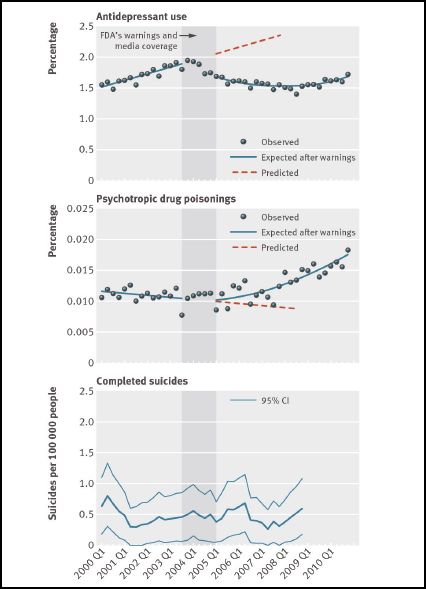

Fig. 1 Rates of antidepressant use, psychotropic drug poisonings, and completed suicides per quarter before and after the warnings among adolescents enrolled in 11 health plans in nationwide Mental Health Research Network

Adolescents (10-17)

The graph is divided into three parts. The upper part shows antidepressant use, quarter by quarter, for the period of the study (2000, q1 – 2010, q4). Each dot represents the percentage of the 1.1 million adolescents that were taking antidepressants in that particular quarter. So in the first quarter of 2000, a little over 1.5% were taking the drugs, and so on.

The middle part of the figure shows the percentage of adolescents who were treated for psychotropic drug poisoning in each quarter.

And the lower part shows the number of completed suicides (per 100,000) in the group, plotted quarterly, and graphed as a continuous line (the dark green line) rather than as dots. The lighter lines represent the 95% confidence interval. In other words, the chances are 95% that the true suicide rate for the population lies between these lines.

The slightly darker vertical band that goes up through the middle of all three graphs is the phase-in period (2003, q 4 – 2004, q4). The solid lines in the upper and middle sections are the regression lines for the pre and post warnings data. The post lines are curves because the authors report that this fitted the data better. The orange dotted lines in the post area are simply the projection of the pre-warning regression lines; i.e. a projection of what purportedly would have happened if the warnings had not been issued. Completed suicide data for the last two years of the study was not available.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

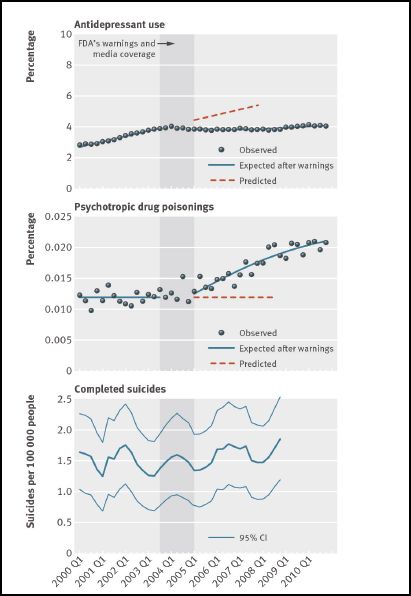

The data for the young adults (Fig 2) is presented similarly.

Fig 2 Rates of antidepressant use, psychotropic drug poisonings, and completed suicides per quarter before and after the warnings among young adults enrolled in 11 health plans in nationwide Mental Health Research Network

Young Adults (18-29)

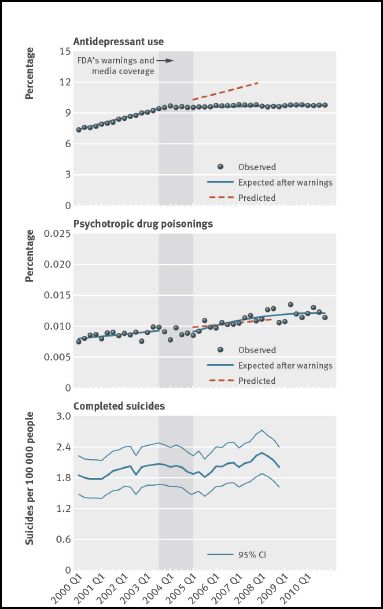

The data for older adults is shown in Fig. 3

Fig 3 Rates of antidepressant use, psychotropic drug poisonings, and completed suicides per quarter before and after the warnings among adults enrolled in 11 health plans in nationwide Mental Health Research Network

Older Adults (30-64)

The FDA warnings were not aimed at adults. The authors state that the adults were included in the study “…as a ‘control’ group.”

From all of this data, the authors draw the following results/conclusions:

1. The FDA safety warnings, plus the media coverage, “decreased antidepressant use.”

2. There were simultaneous increases in suicide attempts by young people.

3. It is essential to monitor “unintended consequences” of black box warnings and media reporting.

4. Completed suicides did not change for any group.

The main thrust of the article is expressed in the final paragraph:

“Undertreated mood disorders can have severe negative consequences. Thus, it is disturbing that after the health advisories, warnings, and media reports about the relation between antidepressant use and suicidality in young people, we found substantial reductions in antidepressant treatment and simultaneous, small but meaningful increases in suicide attempts. It is essential to monitor and reduce possible unintended effects of FDA warnings and media reporting.”

Again, we see the rebuking tone aimed at the FDA and the media.

NIH Press Release

As mentioned earlier, the study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which is a division of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study was published on June 18. On June 19, NIH issued a two-page press release via its own website, Medline Plus.

Here are some quotes from the press release, interspersed with my comments and observations.

“Teen suicide attempts rose nearly 22 percent after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned about dangers of antidepressants, a new study finds.”

This statement is false. What the study found was that within the HMO Research Network’s insurance plans in ten states, psychotropic drug poisonings (including, incidentally, according to the press release, poisonings by marijuana, amphetamines, and Ecstasy), that required medical treatment, rose by the stated amount. This is only one method of attempting suicide, and in many cases might not be attempted suicide at all. The study provided no information on the incidence of confirmed suicide attempts measured as such. Incidentally, ICD-9 code 969, which Lu, et al., used as a proxy measurement for suicide attempts, also includes “poisoning by caffeine”!

The statement is also misleading, in that the changes in the rates of psychotropic poisonings were measured not against the previous rate of poisoning as is implied in the above quote, but against the projected rate, based on the 2000 – 2003 regression line. This is critical because regression lines can be extraordinarily poor predictors, as any stock market analyst can attest.

Regression lines are also easy to manipulate by the simple expedient of delineating the time boundaries to show a desired trend. In the present study, for instance, the exclusion of the phase-in data from the pre-warning regression analysis definitely had the effect of lowering the poisoning trend projection in the young adult group (Fig 2), and probably had this effect in the adolescent group (Fig 1). Excluding the phase-in data from the regression analysis was an arbitrary decision. The researchers might just as readily have used a simple pre-post cutoff based on the quarter in which the warnings were mandated.

It is also noteworthy that the percentage changes in antidepressant prescriptions and psychotropic poisonings were assessed solely on the 4th quarter of 2006. The authors’ statement on this matter is interesting:

“In addition, we also provided absolute and relative differences (with 95% confidence intervals)…in the second year after the warnings (that is, in the last quarter of 2006), which were estimated by comparing the overall changes in outcome attributable to the warnings with counterfactual estimates of what would have happened without the warnings.”

Note the unwarranted causal implication (“attributable”), and the assumption that the authors knew what would have happened had the warnings not been issued. “Counterfactual” according to my Webster’s means “contrary to fact.” I’m not sure what the authors had in mind in describing their projections this way.

There is also, I think, a suggestion in the above quote that the result applies to the general population. This, however, would only be the case if in fact the group of individuals studied had been selected at random from the US population. This is emphatically not the case. The study group comprised all the individuals between ages 10 and 65 who were enrolled in the eleven MHRN insurance groups in the 12 states.. This group, for instance, is certainly not representative of uninsured people, nor of people in other locations.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Following the warnings, antidepressant prescriptions for young people fell by more than a fifth. At the same time, suicide attempts rose, possibly because depression was being undertreated, according to background information in the study.”

This statement is false. What the study found was that antidepressant prescriptions for adolescents (10-17) declined from a peak of about 1.9% in 2003, q3 to a low of about 1.3% in 2008, q2, and then climbed to about 1.7% in 2010, q 3 (Fig 1). But the figures for young adults (18-24), who are presumably included in the term “young people” as used above, remained remarkably constant at about 4% from 2004, q1 to 2010, q4. The only “fall” for this group is a notional fall from the trend line. (Fig. 2)

Again in this quote, we see the implied causal link to suicide attempts, and even a suggested explanation: “possibly because depression was being undertreated.” The study provides no information on general nationwide trends in the frequency of suicide attempts, and even if suicide attempts were trending upwards during the period in question, there are many other possible explanations. Also in this quote we see the invalid substitution of the term “suicide attempts” for psychotropic drug poisonings.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“‘We found a substantial reduction in use of antidepressants in youth, and also in adults — who were not targeted by the warning,’ said lead author Christine Lu, an instructor in population medicine at the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston.”

Here again, this statement is false. The antidepressant use data for young (Fig 2) and older (Fig 3) adults remained almost perfectly flat in the post-warning period. As noted earlier, the only falls were from the projected trend lines.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Lu attributes the drop in prescriptions to the FDA’s warning and resulting media coverage. ‘To a certain extent, the FDA’s black box warning was legitimate, but the media emphasis was really on suicide without noting the potential risk of undertreatment of depression. Because of that, there has been an overreaction, and that overreaction has sent alarming messages to parents and young people,’ she said.”

Note the skilful tightrope walking. Dr. Lu and the NIH want to bash the media for publicizing the link between antidepressants and suicidal activity, but at the same time not overly antagonize the FDA. The media ignored the “potential risk of undertreatment”; the media overreacted; the media caused alarm. Big bad journalists need to get into line!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Then we have a truly magnificent piece of psychiatric spin:

“Although the initial studies showing an increased risk of suicide in teens taking antidepressants prompted the black box warnings, researchers never proved that the medications were the cause of the increased risk of suicide, only that there was a link.

Likewise, though the current research finds a strong association between the uptick in suicides and the drop in antidepressant use, Lu and her colleagues weren’t able to definitively show that a decrease in antidepressant prescriptions was directly responsible for the recent increase in suicide attempts.”

The deliberations and the data on which the FDA black box warnings were based were comprehensive, and showed a clear link between antidepressant use in young people and suicidal activity. And the evidence was sufficient to convince the FDA to take action.

The findings in the Lu, et al., study do not come even close to this standard. But by counterposing them in this way, the NIH is trying to convey the impression that the findings of the present study are comparable in quality to the earlier work.

Note also the blatant falsehood: “…the current research finds a strong association between the uptick in suicides and the drop in antidepressant use…” [Emphasis added] In fact, the Lu, et al., study found no increase in completed suicides. They stated clearly in their abstract: “Completed suicides did not change for any group.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Coverage of the warning may have had unintended consequences, Lu said. Doctors may have been less willing to prescribe antidepressants and parents may have been fearful of letting their children take them, she said.

The lesson, Lu said, is that the media and the FDA should strive for the right balance so potential overreactions don’t occur.”

Again, big bad media needs to get in line and print only what psychiatrists tell them to print (“the right balance”).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Undertreating depression is worse than the slight increase in suicidal thoughts antidepressants may cause, Lu said. ‘It’s also a reminder for doctors to weigh the risk of a drug with the risk of not treating or undertreating the condition,’ she said.”

This is extremely misleading. Note how the concerns on which the boxed warnings were based are dismissed: “…the slight increase in suicidal thoughts antidepressants may cause.”

The pediatric meta-analysis data on which the FDA deliberated in 2003-2004 are written up in detail (131 pages) here. Tarak Hammad et al published the formal journal report in 2006. It is clear that great pains were taken to include in the primary outcome measure only adverse events that had clear suicidal potential. The primary outcome, which was labeled “suicidal behavior or ideation,” contained three elements:

- Suicide attempts, and/or

- Preparatory actions towards imminent suicidal behavior, and/or

- Suicidal ideation

The overall risk ratio (drug vs. placebo) for the three elements combined was found to be 1.95 (95% CI, 1.28 – 2.98). The risk ratio for suicidal behavior (first two items) was 1.90 (95% VCI, 1.00 – 3.63). In other words, the individuals in the studies who took the drug were about twice as likely to have made a suicide attempt, and/or made preparations for imminent suicide, and/or had been actively thinking about suicide than those who took the placebo. This is emphatically not something to be dismissed as “a slight increase in suicidal thoughts…”

Hammad et al acknowledged the limitations of their study, but went on to state:

“Despite the limitations, the observed signal of risk for suicidality represents a consistent finding across trials, with many showing RRs [risk ratios] of 2 or more. Moreover, the finding of no completed suicides among the approximately 4600 patients in the 24 trials evaluated does not provide much reassurance regarding a small increase in the risk of suicide because this sample is not large enough to detect such an effect.”

They also provide the following interpretation of their findings:

“…when considering 100 treated patients, we might expect 1 to 3 patients to have an increase in suicidality beyond the risk that occurs with depression itself owing to short-term treatment with an antidepressant.” [Emphasis added]

In addition, since the issuing of the black box warnings in 2004, there have been two studies confirming the link between suicidal activity and antidepressants.

Olfson et al 2006 found:

“…in children and adolescents (aged 6-18 years), antidepressant drug treatment was significantly associated with suicide attempts (OR [odds ration], 1.52; 95% CI, 1.12-2.07 [263 cases and 1241 controls]) and suicide deaths (OR, 15.62; 95% CI, 1.65-infinity [8 cases and 39 controls]).”

And Olfson et al 2008 found:

“Among children, antidepressant treatment was associated with a significant increase in suicide attempts (odds ratio [OR] = 2.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06 to 4.10; cases, N = 51; controls, N = 239; p = .03).”

Press Coverage

The Lu, et al., article, and the authors’ conclusions, received wide coverage in the general media. Most of the mainstream media simply regurgitated the gist of the study plus the press release with additional quotes from two of the authors, Christine Lu, PhD, and Steven Soumerai, ScD, both from Harvard’s Department of Population Medicine.

Both the Washington Post and The Boston Globe delivered the authors’ message pretty much without reservation. Here’s a quote form the Washington Post:

“…Wednesday’s study wrote that while the government’s actions in 2003 and 2004 were legitimate and thorough, ‘FDA advisories and boxed warnings can be crude and inadequate ways to communicate new and sometimes frightening scientific information to the public.’ Likewise, researchers argue that while media attention can create much-needed awareness…sometimes ‘the information may be oversimplified and distorted when communicated in the media.'”

And from The Boston Globe:

“The study’s authors say that patients and doctors, frightened by news coverage that exaggerated the risk of antidepressants, shunned treatment that might have prevented the suicide attempts.”

In fact, there is no information in the report as to whether the victims of the poisonings had taken antidepressants or not.

And amazingly,

“Steven B. Soumerai, a coauthor and a Harvard professor of population medicine, said black box warnings typically have little effect on physician behavior, unless they are accompanied by news reports.”

In his attempt to castigate the press for publicizing the black box warnings, has Dr. Soumerai inadvertently shot psychiatry in the foot? Do psychiatrists actually pay more attention to news reports than to FDA warnings?

Bloomberg also ran the standard story:

“A widely publicized warning by U.S. regulators a decade ago about risks for teenagers taking antidepressants led to plummeting prescriptions and increased suicide attempts, Harvard University researchers said.”

Note the clearly implied causality (“led to”), the exaggeration (“plummeting”) and the mischaracterization of psychotropic poisonings as “suicide attempts.”

“‘After the widely publicized warnings we saw a substantial reduction in antidepressant use in all age groups,’ said Lu, an instructor in population medicine at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, in a telephone interview. ‘Warnings, especially widely publicized warnings, may have unintended consequences.'”

“Lu said the focus by the media on the risk of suicide, even though the review of data found no increase in completed suicides, frightened patients and parents.”

Again, the big bad media frightening patients and parents.

But Bloomberg also obtained some rebuttal quotes from Marc Stone, MD, a senior medical reviewer at the FDA:

“‘It’s a stretch to say that the people that are committing suicide or the increase in suicide attempts has to do with the prescription of antidepressants,’ Stone said in a telephone interview. ‘There’s absolutely nothing in the study to say that these are the people who would have been prescribed the antidepressants if it weren’t for the warnings.'”

“There are other issues that could be influencing the drop in antidepressant prescription and rise in poisonings, Stone said. The data presented in the study shows a steady increase before the warnings in antidepressant prescription rates for adolescents while drug poisonings remained relatively steady. The rise in poisonings after the warnings when prescriptions declined slightly in that group doesn’t show a link between the two events, he said.

‘They’re describing a very strange phenomenon in society that’s supposedly being held back by antidepressant use,’ Stone said. ‘It doesn’t stand up to what we know about the mental health situation in the United States.'”

I could find nothing in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, or the LA Times about the study or the press release.

Medscape, a web resource for physicians and other health professionals, toed the party line:

“The safety warnings were covered widely in the media and led to a decrease in antidepressant use by young people, but at the same time, there was an increase in suicide attempts, Christine Y. Lu, PhD, of the Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and colleagues found.”

Again, note the inaccurate characterization of drug poisonings as “suicide attempts.”

“The researchers say that it is possible that the warnings and extensive media attention led to ‘unexpected and unintended population level reductions in treatment for depression and subsequent increases in suicide attempts among young people.'”

And the focus on the “extensive media attention.”

The APA drew attention to the Lu, et al., study in a Psychiatric News Alert, but the tone of the piece was appropriately and, I must say, surprisingly, skeptical. The only quote was from Mark Olfson:

“Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center and an expert in mood disorders, told Psychiatric News that ‘the new findings shed little light on the complex associations between anxiety and depressive disorders, antidepressant treatment, and the risk of self-harm and suicide. The measure of suicide attempts used in this study, psychotropic poisonings (ICD-9 code 969), is only loosely related to suicide attempts. Most suicide attempts in young people do not involve poisoning by psychotropic drugs and most intoxications do not represent suicide attempts.’

Because of the recent substantial increase in unintentional poisonings from stimulants, Olfson stated that the increase in psychotropic overdose could be a result of an underlying substance use disorder rather than suicide. ‘This trend [of psychotropic overuse by youth], which may be driven by complex societal factors, deserves study and clinical attention,’ Olfson concluded.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Finally, the most reasonable interpretation of the Lu, et al., data is that following the black box warnings, the long-standing increase in the use of antidepressant drugs was halted, but suicide rates remained about the same (N = 7.5 million).

Some History

This is not the first attempt to discredit/undermine the black box warnings for these drugs. In September 2007, Robert Gibbons, PhD et al published Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents in the American Journal of Psychiatry. The paper was based on a study of US and Dutch SSRI prescription rates to children and adolescents from 2003 to 2005, and was funded by NIMH grant. The authors reported the following results:

“SSRI prescriptions for youths decreased by approximately 22% in both the United States and the Netherlands after the warnings were issued. In the Netherlands, the youth suicide rate increased by 49% between 2003 and 2005 and shows a significant inverse association with SSRI prescriptions. In the United States, youth suicide rates increased by 14% between 2003 and 2004, which is the largest year-to-year change in suicide rates in this population since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began systematically collecting suicide data in 1979.”

And drew the following conclusions:

“In both the United States and the Netherlands, SSRI prescriptions for children and adolescents decreased after U.S. and European regulatory agencies issued warnings about a possible suicide risk with antidepressant use in pediatric patients, and these decreases were associated with increases in suicide rates in children and adolescents.”

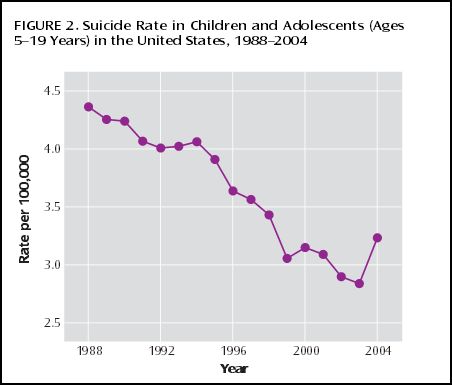

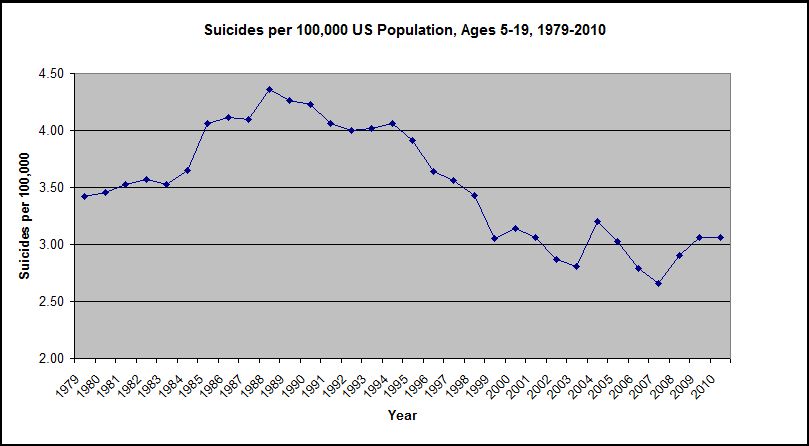

The report contains a graph showing a sharp increase in suicide rates for children and adolescents (5 – 19) between 2003 and 2004.

The data for this graph was extracted from the CDC WONDER Compressed Mortality Database (up to 2002) and from the CDC WISQARS Injury Mortality Report Database (2003 – 2004). On the face of it, this graph does seem to show a dramatic increase in completed suicides for this age group between 2003 and 2004. But when we look at the bigger picture, this trend is not so obvious.

On July 1, I extracted completed suicide rate and population data from the CDC website for the period 1979 to 2010. The Gibbons et al graph is for ages 5 – 19. I was unable to obtain that graph from the CDC site, but I was able to collate the raw data and draw the graph using Excel software. Here’s the graph:

As can be readily seen, the increase in the suicide rates for this age group from 2003 to 2004 does not appear as marked or as noteworthy when viewed against the wider background. Drawing conclusions from short-term trends is fraught with potential for error. Dr. Gibbons et al were obviously aware of these issues, and provided a lengthy discussion/argument in support of the relevance of the associated trends. Nevertheless, here’s their closing paragraph:

“In December 2006, the FDA’s Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee recommended that the black box warning be extended to cover young adults, and in May 2007, the FDA asked drug manufacturers to revise their labels accordingly. If the intent of the pediatric black box warning was to save lives, the warning failed, and in fact it may have had the opposite effect; more children and adolescents have committed suicide since it was introduced. If as a result of extending the black box warning to adults there is a 20% decrease in SSRI prescriptions in the general population, we predict that it will result in 3,040 more suicides (a 10% increase) in 1 year (17). If the FDA’s goal is to ensure that children and adults treated with antidepressants receive adequate follow-up care to better detect and treat emergent suicidal thoughts, the current black box warning is not a useful approach; what should be considered instead is better education and training of physicians.”

The Washington Post ran an article on the Gibbons et al study, Youth Suicides Increased As Antidepressant Use Fell, September 6, 2007. The article included the following quotes:

“Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, said, ‘We may have inadvertently created a problem by putting a ‘black box’ warning on medications that were useful.’ He added, ‘If the drugs were doing more harm than good, then the reduction in prescription rates should mean the risk of suicide should go way down, and it hasn’t gone down at all — it has gone up.'”

“The trend lines do not prove that suicides rose because of the drop in prescriptions, but Gibbons, Insel and other experts said the international evidence leaves few other plausible explanations.”

Given the behavior of the trend line since 2004, these quotes suggest, at the very least, an over-reaction from the authors and from the NIMH. And the fact that the NIMH funded both studies suggests that they may have an agenda: to promote antidepressant drugs as safe, and to downplay any indications to the contrary.

If the NIMH genuinely wants to explore the sources/causes of suicide, they need to recognize three facts:

1. Suicide is a complex, psychosocial phenomenon, and its roots/causes vary enormously from individual to individual, and from community to community. Psychiatry routinely asserts that the root, or major cause, of suicide is depression, but this assertion is meaningless because suicidal activity/rumination is one of psychiatry’s defining features of depression. A genuine understanding of human actions involves so much more than assigning labels.

2. The facts surrounding any completed suicide are always, by the nature of the matter, at least partially hidden.

3. Any attempt to understand suicide must involve a detailed, open-minded exploration of individual cases. Variables that appear associated with suicide trend lines provide, at best, suggestions that might inform these explorations, but can also be very misleading.

Anecdotal Information

At the present time, there is a great deal of anecdotal information, on the Internet and elsewhere, to the effect that individuals who were not previously suicidal, became so, shortly after starting SSRI’s. The psychiatrist Joseph Glenmullen drew attention to this graphically and convincingly in Prozac Backlash (2000). Here’s a quote:

“…the key elements in these stories appeared to be the ‘dramatic change’ observed in these people after starting Prozac, how ‘out of character’ their behavior was on the drug, and the often extraordinary degree of violence not only toward themselves but toward others.”

Elsewhere in the book, Dr. Glenmullen makes it clear that his comments apply, not only to Prozac, but to all drugs in the SSRI category. Psychiatrist Peter Breggin has made similar points. AntiDepAware has accumulated an enormous amount of anecdotal information on this matter.

Psychiatry tends to dismiss these kinds of concerns as “anecdotal.” In this context, “anecdotal” usually means: based on casual or incidental information rather than on systematic observations and evaluations. In particular, the term suggests a subjective, rather than an objective approach.

But in fact, the raw data for virtually all psychiatric research is anecdotal in this sense. If a person reports suicidal ruminations after taking an SSRI, this is anecdotal. But if a study participant reports that he’s feeling better after taking an SSRI, this is also anecdotal. And if 20 people make essentially similar statements, that’s 20 anecdotal statements. And if they make these statements by answering 17 questions on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, then we have 340 anecdotal statements. The fact that the HDRS-17 is widely used, and yields numerical data which can be collated into rows and columns and analyzed with sophisticated computer programs doesn’t alter the fact that the raw data is anecdotal.

No one on this side of the issue is suggesting that a large proportion of people taking antidepressant drugs kill themselves. If that were the case, then the drugs would have been removed from the market long ago. What is being contended, however, is that these drugs are inducing strong suicidal urges in a relatively small proportion of individuals who had not previously had thoughts of this kind, and that some of these people are succumbing to these urges, and are taking their own lives. That is indeed anecdotal information. But it’s also very important, and it warrants investigation even if it involves only a fraction of one percent of the people taking the drugs. To dismiss these widespread and credible contentions on the basis of the dogmatic insistence that the drugs are wholesome, or that the individuals were probably suicidal to begin with, is simply unconscionable. This is particularly the case in that firstly, the proof of the wholesomeness of these products is also, ultimately, based on anecdotal information, and secondly, there is no way to reliably identify the individuals concerned prior to prescribing the drugs.

Prescribing these psychoactive drugs is like playing Russian roulette with someone else’s life. The notion that this information should be suppressed because it might scare people from taking the products is cruel, callous, and irresponsible. Psychiatry’s persistent and self-serving efforts to suppress this information is a national, and indeed, worldwide, scandal.

The Lu, et al., study, and the NIH press release, reminds me of a statement made by Patrick B. Kwanashie, Assistant Attorney General in Connecticut, after the Adam Lanza murders/suicide:

“Even if you can conclusively establish that Adam Lanza’s murderous actions were caused by antidepressants, you can’t logically from that conclude that others would commit the same actions as a result of taking antidepressants. So it’s simply not legitimate, and not only is it not the use to which they are proposing to put the information not legitimate, it is harmful, because you can cause a lot of people to stop taking their medications, stop cooperating with their treating physicians just because of the heinousness of what Adam Lanza did.”

Psychiatry’s Suppression of Information

The Lu, et al., study has been subjected to a great deal of criticism. These criticisms have been cogent and valid, but there is also a bigger picture. The Lu, et al., study was never meant to be about science. It was about spin and PR. Its purpose was to attack and embarrass the media in order to keep them in line. The fundamental message in the study, and in the NIH press release, is: If you reporters print bad things about antidepressants, this will lead to reduced usage of these products, which in turn will lead to more suicides, and you will have blood on your hands! Psychiatry is intellectually and morally bankrupt. It has no valid response to its critics and is increasingly resorting to this kind of spin and PR.

Organized psychiatry realizes that it has lost the present debate on its logical/scientific merits. They realize that their only hope for survival as a profession hinges on their ability to control the media. In the pursuit of this objective, there truly are no depths to which they will not sink.

Over the past two decades, I have become convinced of two things:

1. SSRI’s, and possibly other psychiatric drugs, are inducing strong suicidal and violent urges in some people.

2. This information is being systematically suppressed by psychiatry and by the NIMH. To the extent that they acknowledge it at all, they pretend that this suppression is in the public interest.

If there was ever a time when we need courageous and well-informed reporting, it is now. Let us hope that the press has sufficient integrity and courage to resist psychiatry’s tawdry blackmail, to follow the evidence, and to print the truth. In this context, it is very encouraging that neither the New York Times, nor the LA Times, nor the Wall Street Journal took the Lu, et al., bait.

It is time to end the charade. The link between psychiatric drugs and suicide/violence needs urgent study by independent, adequately funded investigators who are given access to all the information.

* * * * *

This article first appeared on Philip Hickey’s website,

Behaviorism and Mental Health

My question for Christine Lu would be; if psychiatric drugs really do prevent suicides how many young people do we need to start down the path of lifetime of psychiatric drug taking and disability to save that one young person from suicide ?

10, 100, 1000, 10,000 ?

Report comment

Call me selfish but I wouldn’t do the psych med nightmare again to save the next guy from suicide.

Report comment

Copy_cat,

That’s a great question!

Report comment

And according to your graph, it seems the increased drugging of children in the early 1990’s, and the potential and seemingly actual increased suicide levels of children on these drugs, at the exact same time the psychiatric industry was pushing so many antidepressants and ADHD drugs onto children, may also have resulted in Joseph Biederman’s claims that the drugged kids needed to be put on the antipsychotics ( to decrease suicide levels, and increase antipsychotic / major tranquilizers sales.)

How do the type of drugs given, and stigmatizations given, relate to this study? My personal experience with drug induced suicides is of youth throwing themselves in front if trains or lighting themselves on fire, out of despair at the stigmatization, and appalling drug effects is heartbreaking. How is defaming and force medicating children, what the UN calls “torture,” acceptable any longer?”

Report comment

Someone Else,

There certainly appear to be some genuine trends in the graph, but I don’t know what factor(s) are driving these trends.

Report comment

I’d rather ask why the authors didn’t try to figure out which of the kids supposedly trying suicides weer indeed not prescribed anti-depressants at the time. I’m not sure you can find this data in that particular database but if indeed then it’d strike me as lazy to say the least. Also there could be another explanation for the trend (which is bogus to begin with but let’s take it at face value) – withdrawal. If people took antidepressants and stopped them – we all know how bad this can go. In general there is a million problems with this study…

Report comment

Hence, all warnings ought to be removed from all currently regarded dangerous substances as well as other sorts of dangers . . . they just induce the behavior one wished to prevent. I wonder how many people put flammable substances near a hot stove after reading they are highly flammable? The temptation must be greatly increased by the challenge. Or people that overdose on over the counter drugs like Advil? Etc. The discovery here will revolutionize labeling.

Or, ought we to conclude something else? Perhaps we ought to.

Report comment

AgniYoga,

Yes. And information about dangerous ignition switches should be suppressed, because it will make people fearful of using their cars!

Report comment

Anti depressants will never work, as pointed on the Star Trek episode This Side Of Paradise

“Happiness Comes From Struggle ” http://youtu.be/19o4IhxifNw

Report comment

Copy_cat,

Very wise words!

Report comment

Dr. Hickey,

This is another very thorough, hard hitting excellent article on the ongoing SSRI antidepressant debacle/

Have they no shame? Oh, right. You answered that by saying psychiatry is intellectually and morally bankrupt.

If one is on to their PR spin games, it’s hard to stomach a lot of their articles since they have obviously been written by people with no conscience, empathy or concern for their fellow humans. But, the fact that these lies have been spread so widely through the media to push these toxic drugs on children/teens when they have been shown to have little if no efficacy beyond placebo in many studies and are known to cause suicide, violence, mania, apathy and many other dangerous side effects shows that many practicing psychiatry especially the KOL’s at the highest level are very dangerous, character disordered intraspecies predators in my opinion.

Report comment

Donna,

It is indeed hard to stomach. And what they lack in validity, honesty, and logic, they try to make up for in salesmanship and spin of the extremely sordid variety.

Report comment

Well, if they have all the data it should be very easy to determine how many of the kids who attempted suicide were on anti-depressants at the time instead of just showing how many tired to do it. Additionally the criteria for attempted suicide is so bs that it should not even be treated seriously…

Report comment

Wow, you show some remarkable examples of data manipulation. Measuring the increases/decreases in trends against projected data instead of actual data is amazing, or cutting the graph at the point where the trend line stops fitting into your hypothesis are at the very least bad science at the worst misconduct…

I just have one note on the anti-depressants and suicide: I have recently returned from a neuroscience conference where I saw a very interesting poster showing some mouse studies on effects of SSRIs and environment on depressive-like symptoms induced by chronic stress. In short, stressed mice were divided into 4 groups:

placebo group transferred to enriched environment (“recovery” scenario)

placebo group transferred to stress-inducing environment (“no recovery” scenario)

SSRI in enriched environment

SSRI in stress-inducing environment

The results were interesting: the group on SSRI in recovery-inducing environment did slightly better than placebo kept in the same environment in some tests (or comparable on others). However, for mice remaining under stress the placebo group did far better than SSRI which deteriorated at a much bigger rate.

Of course these are short term studies on mice but if translatable to people suggest that simply dumping SSRIs on someone and leaving them in a hole does more harm than good and the only use of these drugs (if they’re needed at all) must come with or proceeded by a significant change in somebody’s life circumstances. Well, not surprising I guess to people at MIA…

Report comment