The biweekly Mad in America Parent Resources Q&A section is a safe place to ask questions and share concerns about children, families, and alternatives to conventional psychiatric treatments and have them answered on site by one of our subject experts. Please email your questions to [email protected]. Your identity will be kept confidential. Questions may be edited for length and clarity. An archive of past Q & A’s can be found here.

Question:

My son was diagnosed with schizophrenia five years ago and now lives in a residential facility with a holistic treatment approach. He has suffered much but is emerging as a kind and creative guy focused on his treatment (medication, therapy, meditation, sobriety, and health) and working towards his goals.

However, his father has repeatedly and aggressively tried to coerce him to get off medication, telling him that he will only recover if he stops taking them. My son and his provider have repeatedly asked him to stop, and the stress of his father’s pressure is setting him back. What should we do?

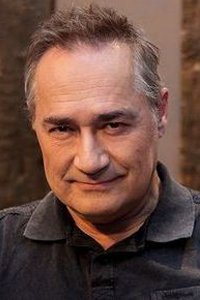

Reply from Ben Furman, M.D.:

Years ago, I worked as a psychiatrist in a psychiatric hospital in a rural town here in Finland during the summer months. The nurses there complained to me that there was a small but vigorous religious sect in town that tried to undo their good work by convincing patients to discontinue their medication after their release from the hospital. Following the adage, “if you can’t beat them, join them,” I suggested we organize a celebration at the hospital in honor of our patients and invite their families and community members — including the aforementioned sect.

Sure enough, when the celebration took place a couple of weeks later, members of the sect were among the guests. We even granted them permission to sing a few of their chants — accompanied by an accordion — on the corridor of our ward. That one day made a big difference in our relationship with people we had perceived to be our number-one adversary.

Learning to Listen

There are many beliefs about the best way to help people suffering from mental health crises, and it’s unlikely that we will ever reach a consensus. The readers of this website are likely to have heard about an increasingly popular treatment approach known as “Open Dialogue,” which offers a way of allowing differing opinions to be voiced and heard. Everyone has the right to his or her views, and everyone’s views are acknowledged. When people feel that they have been acknowledged, it becomes easier for them to hear and acknowledge others.

However belligerent your son’s father may seem, please be kind to him. Acknowledge his opinion. Perhaps your son will be able to discontinue his medication when the time comes. If he recovers well, in a few years he may be on track to try to taper off his medication under controlled conditions discussed with his healthcare providers and with support from family and friends. At that point, you may be able to tell the father sympathetically, “You were right, but your timing was too hasty.”

Long vs. Short-term Drug Use

Given your son’s diagnosis, I assume that he is taking prescribed neuroleptic drugs. I like to think of neuroleptics not so much as medication but as a kind of doping, like the substances athletes use to improve their performance. The drugs do not cure psychosis but do tend to sedate the brain. When the brain is running amok, producing hallucinations and delusions, a bit of sedation can indeed be helpful. The patient may consider their side-effects worth the price, at least for a while. A Bulgarian colleague of mine has demonstrated that when drugs are presented to patients as “doping substances” that can help them achieve their goals, rather than medicines for a crippling condition, the patients’ compliance to treatment is greatly improved.

Finally, I think you should talk to your son and help him find a way to respond constructively to his father’s convictions. There is often a small voice inside patients telling themselves similar things, so practicing responses to his father can help him learn to respond well to his inner voice, too. Perhaps he could say something like, “Dad, I know you mean well, and I have the feeling that the day will come when I will try to wean off my medication and follow your advice. Right now, I still feel I need the medication for some time because it stabilizes me, so I can benefit from my therapy. I know you want the best for me and I’d appreciate it if I could have your support.”

Navigating the choppy waters of differing and sometimes conflicting opinions and beliefs about mental health can be frustrating not only to service users but also to family members. The best way to handle these divisions is to show curiosity, allow everyone to have a voice, and then do what seems best.

Ben Furman is a Finnish psychiatrist and an internationally renowned teacher of solutions-focused therapy. He is the founder of the child-friendly Kids’ Skills method, which is based on the idea of converting children’s problems into skills that children can learn with the help of their family and friends. For more information about Ben, visit www.benfurman.com. The Kids’ Skills app is available for download at www.kidsskillsapp.com.

Ben Furman is a Finnish psychiatrist and an internationally renowned teacher of solutions-focused therapy. He is the founder of the child-friendly Kids’ Skills method, which is based on the idea of converting children’s problems into skills that children can learn with the help of their family and friends. For more information about Ben, visit www.benfurman.com. The Kids’ Skills app is available for download at www.kidsskillsapp.com.

Editor’s note: Mad in America supports informed consent in the prescription and use of psychiatric drugs. You may wish to review our The Science of Psychiatric Drugs section. Our new “Psychotropic Drugs in Children and Adolescents” section provides information about ADHD drugs; information about other medications will follow soon.

The truth is that the psychiatrist has replaced the father. That’s why the son obeys the psychiatrist, that’s why the father rage. Behind the question of the drug, there is the substitution of paternal authority.

Typical systemic problem in which the psychiatrist participates: “schizophrenia” is always a systemic problem.

Report comment