In the 1960s and 1970s, the Italian mental-health system was in the midst of revolution.

Ignited by the psychiatrist Franco Basaglia—who had seen patients strapped down, silenced, abused, and incarcerated—it began in the city of Trieste. From there, Italy instituted nationwide reform, culminating in the Italian Mental Health Act of 1978, or the “Basaglia Law.” Psychiatric hospitals were gradually shuttered. Treatment was moved to community-based care.

But as the organizers of Mad in Italy repeatedly, passionately express, Italian mental-health care still runs on the biomedical model. Disease is still the paradigm; psychotropic drugs are still the standard approach. And revolution, they say, is still necessary—in Italy, and around the world.

The only question: How to get there.

“Strategy is really important . . .We want to be goal-directed. We don’t want to be beating around the bush,” said Marcello Maviglia, cofounder and co-administrator of the nearly two-year-old Mad in America affiliate.

“I don’t believe in being a Don Quixote. I don’t want to fight against the windmill. I am aware that we are frail. We have limitations,” he said. But given the wide reach of MIA’s global community, “I’m also aware that we have a huge audience.”

Maviglia, a psychiatrist and behavioral health specialist based at the University of New Mexico, runs the site with Laura Guerra, a pharmacologist, biologist, and mental-health advocate based in Bolzano, northern Italy. Its main focus is research, publishing articles on failures of the disease model and the effectiveness of alternate, humanistic approaches. The goal is policy change; the means is data.

“It’s evidence-based. It’s science-based,” said Guerra, who translated Peter Breggin’s Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal and, more recently, Joanna Moncrieff’s The Bitterest Pills: The Troubling Story of Antipsychotic Drugs.

The publication of the Breggin translation was a significant moment, Maviglia said. “Before that, nobody was questioning, really, the use of pharmacology . . . Laura brought some science into the debate.”

Guerra has long tried to persuade people that drugs don’t work the way the biological model says they do. She has long worked to disseminate information on withdrawal. Back in 2014, she was a member of La Faretra—an association in Bolzano that advocates for youth mental health rights and organizes conferences on the topic—when she met Mad in America founder Robert Whitaker at an event.

A few years later, she helped create a Facebook page that challenged the pharmacological approach and offered info on psychiatric drug withdrawal: Mat in Italy, with a “T.” Among the stories posted were translations from Mad in America; the page shared content with several other groups devoted to recovery and critical psychiatry. Its reach began to spread.

That was how she met Maviglia. He was a longtime critic of the biomedical model who had participated in the Basaglia campaign before heading to the States for graduate training in psychiatry.

From the start of his career, he was “shocked” by the power and influence of the biomedical paradigm and was deeply versed in psychotherapeutic alternatives. He became even more invested in them after he married an Iroquois woman and started advising on Native American mental health, which is traditionally holistic and community-based. Recently, he helped start a clinic aiding people in withdrawal from psychotropic medications.

But all of that runs counter to the conventional narrative, which Mat in Italy did its best to correct. In the beginning, Guerra said, “consumers were completely surprised about this information—because they only had psychiatrists’ information, which says that ‘Your brain has a chemical imbalance, and you need drugs to balance it.’”

Meanwhile, blowback began from the psychiatric establishment. Certain professionals who follow the biomedical model turned defensive, personally attacking Guerra and Maviglia. “It was evil. It was evil,” he said. She agreed: “It was crazy. . . . Every day, it was a war.”

Eventually, they realized they needed to post their articles and make their points from a more established platform, “something like Mad in America.” In the throes of such disputes, they decided to create an official MIA affiliate in Italy.

It launched in July of 2019. The affiliate retains a kinship with Mat in Italy, with articles and readership criss-crossing both platforms. Mat in Italy has 2,800 members; Mad in Italy’s official Facebook page has 2,283 likes. Together, they said, Mat and Mad in Italy get the word out to providers and users both.

“Even in terms of concrete help,” Maviglia said, “at least we are able to say to people that there is an alternative to drug use: You don’t have to stay on your meds for the rest of your life.”

On Mad-In-Italy.com, the home-page banner features an image from Michelangelo’s fresco from the Sistine Chapel—God’s finger tipping Adam’s with life. Beneath it are pull-down tabs devoted to disorders; drugs; substance dependencies; “Voices from Italy,” including testimonials of lived experience; resources, articles, and videos; and links to MIA global.

Its “Who We Are” page lists Maviglia and Guerra as administrators, along with Antonino Napoli, an activist and meditation instructor with lived experience, and Dan Monticelli, a hypnotherapist, theologian, and author of several books (including New Paths to Recovery: Behavioral, Physical and Spiritual Potentials for Cannabis, coauthored with Maviglia and Geneva Thompson).

But day to day, most of the work is done by Maviglia and Guerra. “We are essentially two,” she said. And funding, he said, is “zero.”

Aside from publishing content, Maviglia and Guerra also provide information to readers who reach out with questions about tapering, withdrawal, or other issues involving psychiatric medication.

They connect each day at 6 a.m., Maviglia’s time, to “address those issues that consumers usually raise,” he said. “We discuss clinical cases on a daily basis with the intent of providing feedback. We are not providing medical care. We frame our feedback as suggestions, which people find to be very useful.”

“Many people thank us for our information,” Guerra added. “I think our information has reached many consumers, and also many psychiatrists.” This is, she said, a ripple effect of the affiliate’s influence.

Which points to more evidence of its impact: The language used by Mad in Italy, and by other reform groups in the country, is seeping into the wider conversation, gradually changing how consumers, providers, and, now and then, even someone in government discuss mental health. Instead of “mental illness,” they’ll use “emotional distress.” Instead of “treatment,” they’ll say “recovery.” Concepts like peer support and the need for psychiatric drug withdrawal centers are also trickling down into the wider conversation.

All of this, Maviglia said, is no small thing. Although he often feels “philosophically and academically isolated” from others in the field of psychiatry, he is confident that Mad in Italy is making a difference. “We are influencing the debate in the media, and probably also in the mental health network,” he said.

In the future, he hopes to increase their “person power” with the addition of staff. He also hopes to collect data “from our members and around Italy” with mental-health surveys that would then be published in peer-reviewed journals and posted online in an effort to reach those in official positions. Such research is a way to alter policy, he said.

“That is our mission, and I think it is doable. . . . I do not believe in setting limits,” he added. If they aimed any lower, they would be “undermining our goals.”

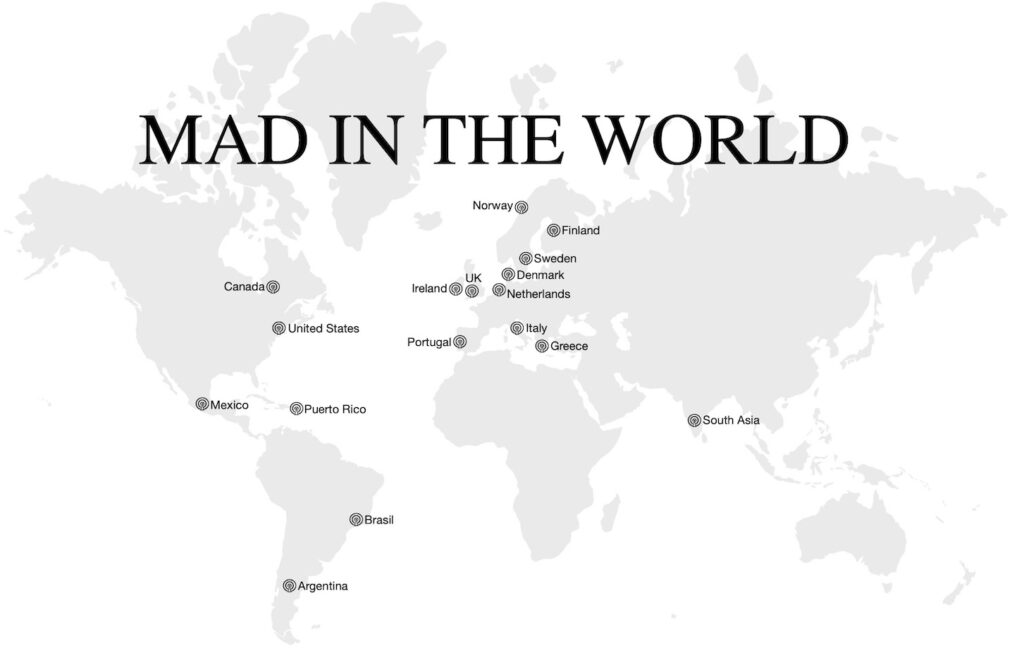

This is one reason being part of the Mad in the World community matters to them. They see that their aims and activism are shared by global colleagues. “We’re very conscious of the Brazilian experience, the Mexican experience, the Latin American experience in general—as well as the European experience,” he said.

They believe in “the synergistic aspect of a network,” he said. They want “to share information, articles, and experiences with the other Mad entities around the world.” They see such international fellowship as key to fostering an agenda with Italian institutions and agencies, constantly pushing for change.

“This international collaboration could translate into something extremely revolutionary,” he said.

*****

MIA Editors: Over the next 10 weeks, we will be publishing a profile of each of the Mad in America affiliates. They have banded together as a “Mad in the World” network.

I think it would be great if someone could fund translations of certain books (Moncrieff, Whitaker, etc.) into many different languages.

Report comment

“Certain professionals who follow the biomedical model turned … evil ….” Most definitely, “certain professionals who follow the biomedical model” will stoop to the lowest levels of criminality to cover up their industries’ scientific fraud and systemic crimes against humanity.

“Every day, it was a war.” And “certain professionals who follow the biomedical model,” indeed, did turn it into a war. Despite the fact that we (the independent and honest psychopharmacological researchers and psych survivors) have overwhelming scientific evidence of the iatrogenic etiology of the two “most serious” DSM “mental illnesses.”

Whitaker’s “Anatomy,” et al, credibly points this out in regards to “bipolar.” And the fact that the anticholinergic drugs (including the antidepressants and antipsychotics) can create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome. And the antipsychotics (aka neuroleptics) can also create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

“This international collaboration could translate into something extremely revolutionary,” let’s hope and pray that happens.

As one who is also an artist, who has noticed Marc Chagall – a Jewish artist who survived the Nazi psychiatric holocaust of the Jews – painted this “war” decades ago. I’d really like to see humanity end “certain professionals who follow the biomedical model” (DSM’s), reign of terror and error. So we may hopefully put an end to the repeating of the worst of human history, and our current “war,” against the scientific fraud of the DSM and psychiatric aspect of the ICD.

Thank you for all your truth sharing Marcello, Laura, Mad(t) in Italy, and MiA.

Report comment

I go along with those who oppose the use of the term “mad” to describe psychiatric inmates and those who have been psychiatrically labeled. This is extremely demeaning and not at all liberating, if that’s the intent.

Report comment