Jay Schulkin was a laboratory neuroscientist, outstanding for his extraordinarily broad perspective that deeply engaged the human condition. His recent books, for example, include: Mind in Nature (2023); The Anatomy of Fear (2024); Suicide in the United States (2024); A perspective on Opiate Addiction (2024).

Jay also deeply engaged the concept of “allostasis”—the relatively recent idea that the brain’s key purpose is to predict what the body will need, and then to coordinate all physiology and behavior to get it. The concept helps explain how social and psychological stresses adversely affect mental and physical health. Jay’s contributions to this topic span several decades, including a book, Allostasis, Homeostasis, and the Costs of Physiological Adaptation (2004), and a significant review, “Allostasis: A Brain-Centered, Predictive Mode of Physiological Regulation” (2019).

Jay managed a wonderful career (and successful life) as an independent thinker on a shoestring. I hope that readers will find this brief eulogy inspiring.

Tolstoy’s Hermit: Jay Schulkin

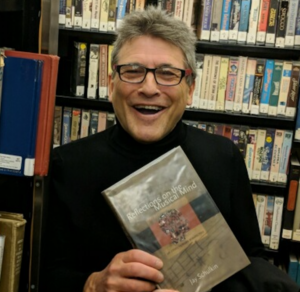

Jay Schulkin, a neuroscientist and philosopher of prodigious curiosity and energy, has died at age 70 of hepatic cancer. According to his wife, April Oliver, “he had a smile on his face and a tear in his eye—completely at peace.”

One colleague remarked that Jay’s research and thought were broad as the Pacific and deep as the Mariana Trench. This applied equally to his wisdom and love. Jay resembled Tolstoy’s wise hermit to whom a troubled king put three questions: When is the best time to do things? Who is the most important one? What is the right thing to do? Jay knew. Only one time is important—now; only one person is important—the one in your presence; only one thing is important—to do good.

And that is how Jay lived—hermit-like in his simplicity and modesty—wearing flip-flops in winter, eating plainly, drinking little, and unconcerned for money or fancy titles. He slept where he tired—4-5 hours on a cot in the lab—and showered in the men’s room. This left him freer than most to live in the now. True hermithood escaped Jay because he was intensely social. He was, perhaps, more like the medicant Siddhartha, traveling the earth with a bowl in confidence that he would be fed. Jay’s openness and courage fostered an astonishing range of long-term friendships and scientific collaborations.

Jay Schulkin was born in New York City on December 29, 1952, and grew up in the Bronx where his dad, who’d survived WWII as a bombardier over Europe, drove a bus, and his mother worked as a hospital administrator. Jay was short, but compact and athletic, reminding one of an old-time halfback before they bulked up so immensely in the gym. He always maintained his athleticism by swimming and walking.

During his hardscrabble youth on very mean streets, Jay earned a Bachelor of Hard Knocks, which delayed until age 23 his matriculation to the State University of New York Purchase. There he studied philosophy, guided by an important mentor, Robert Neville, who became a long-term friend. Following a timely graduation, Jay enrolled in 1978 for a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. However, he soon moved to neurobiology, having been captivated by his studies with George Wolf, a beloved teacher at New York University. Yet Jay always continued to practice philosophy without a license, publishing on topics such as pragmatism and aesthetics, and on his admired philosophers, such as Peirce and Dewey.

In neurobiology, Jay initially focused on a key problem, how the brain and endocrine system regulate our powerful appetite for salt. For these studies, mentored by Eliot Stellar and performed in Alan Epstein’s lab, he was awarded the PhD in 1983. Jay then proceeded to Rockefeller University where he was mentored by Bruce McEwen, a major figure in neuroendocrine regulation. Ultimately, across 45 years Jay published a stunning 523 papers on diverse topics of neuroendocrine regulation, including one soon to appear in the prestigious journal Cell, titled “CRH, Frontal Cortex, and Social Behavior.” CRH (corticotropin releasing hormone) became perhaps Jay’s favorite molecule because of its ubiquity—roles regulating endocrine systems all over the body and brain and, critically, the placenta.

During his graduate and postdoctoral studies, Jay established a peripatetic pattern—that would prove life-long—rotating between his host laboratories at NYU, Penn, and Rockefeller. By distributing his mentors and connecting them “serendipitously,” Jay drew them into collaborations and then into planned projects that, crucially for all, garnered grant funds from the McArthur Foundation and the National Institute for Mental Health. I was added to Jay’s portfolio in 1988 when he intercepted my first paper on “allostasis”—how stress drives the brain to overdrive the body—passing it to Stellar and McEwen, who then coined the term “allostatic load” and popularized it in innumerable publications.

Jay and I might never have met but for his courage in pursuit of clarity. In his lecture to our department of hard-core cell biologists, he had ranged widely—so far as connecting a neuron’s molecular calcium channels to the philosophy of Herbert Spencer. I was captivated, but also wondered if he might have been a little high. He wasn’t, of course, but when my musing reached Jay through a garrulous mutual acquaintance, he accosted me in the hall and asked with a disarming smile if I’d go for a drink and explain my concerns. Thus began my experience of his focused attention and many joyous meetings.

I would share my socio-political concerns, and Jay would confide his direct experience from the streets. I would share some acerbic view of a colleague, and Jay, while understanding perfectly, would take the deeper, more charitable stance. Despite his unclear prospects at 31, Jay never seemed concerned. Then he met April Oliver and married her in 1990, moving to Washington, DC, where she had a “real” job. It seemed that Jay’s catch-as-catch-can lifestyle must end. Instead, it flourished.

In Washington, Jay established connections at the National Institute of Mental Health, first as a research associate in clinical neuroendocrinology and later in a branch for disorders of mood and anxiety. Contemporaneously, he was appointed research professor in Physiology and Biophysics at Georgetown University, and also senior director of research at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Jay even established a research program with the National Zoo. Three of Jay’s publications from 1997 suggest the diversity:

- Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses in temperamentally shy children.

- Treatment of depression by obstetrician-gynecologists.

- Preliminary observations on the relationship of calcium ingestion to vitamin D status in the green iguana.

Jay Schulkin published 37 books on topics ranging from pragmatism to the corporation, from Oliver Wendell Holmes to the biology of lactation, and from the musical mind (Jay played clarinet) to the biology and philosophy of sports. Most were published by leading university presses, including 11 by Cambridge, four by MIT, three each by Oxford, Johns Hopkins, and Columbia, and one by Princeton. One testimonial to their quality must suffice. Jay’s colleague, the outstanding obstetrician, Errol Norwitz, writes that Jay’s book, The Evolution of the Placenta and Birth (2012, with M. L. Powers), “literally changed my life and the course of my research.”

When Jay left Penn, we remained in touch. He’d call maybe once a month, often leaving a brief message: “Hi, thinking of you. Much love,” and a time to call back. Jay would ask about my work and family, and my state of mind; then he’d relate with pride and joy his own news of family and work. Jay rarely complained about his treatment by others, and then it would be his effort to understand and move forward. He proffered advice only on request, and I don’t recall his ever seeking my advice. Apparently, April’s counsel was all he needed. In preparing this document, I discovered that Jay maintained a similar connection with dozens of others, men and women across several continents, and at the highest levels of science and medicine. All describe the identical messages and their identical impact.

Jay expressed such vitality, warmth, and positivity; such empathy, curiosity, and mental energy; such kindness, generosity, and sense of gratitude—it seems at times unreal. I think of a border collie racing to and fro, gathering souls instead of sheep, patiently herding us toward a better place. Since Jay was never in psychotherapy, I wondered how he managed this amazing life on his own terms, and how he acquired the hermit’s wisdom so early?

When I asked recently, Jay responded, “learned a lot from Erich Fromm in Locarno, Switzerland, in the summer of 1974.” But a 22-year-old, no matter how wise the teacher, doesn’t learn all that in a summer. Asked if maybe he’d acquired the tough lessons during his hard-knock adolescence, and if maybe the softer, kinder features were gifts from his mother by whom he was so loved, Jay replied, “Not so far off.”

There isn’t a person on earth who knew Jay who didn’t admire &/or adore him. A gentleman who won’t ever be forgotten.

Larry Isaacs MD (SUNYPurchase classmate)

Report comment

Thank you for this lovely portrait of a lovely, very special man.

Daniel Todes

Report comment

Thank you for this most thoughtful tribute. I have read it at least six times now, and each time I pick up a new gem. This is someone who truly knows my husband.

Report comment