Genetic testing has been hailed as helping bring about personalized depression treatment. Theoretically, people may be genetically suited for some specific drugs and less suited for others. We can now guide the choice of antidepressants based on genetic testing. But does that lead to better outcomes?

Not according to a new study in JAMA Network Open. Researchers tested whether an antidepressant choice guided by genetic testing was better than the antidepressant choice with normal clinical judgment. They found that genetic testing did not affect antidepressant efficacy: 24% of the participants “responded” to treatment, and response rates were similar whether they received the testing or not.

“No significant difference in reduction of depressive symptoms was observed,” the researchers write.

That low response rate is particularly striking, given that recent studies have found much higher responses to placebo. For instance, a Cochrane review found a 42% response rate for drug placebo treatment, even for severe depression, and a ketamine infusion trial found a 57.9% response rate for an active placebo.

The research was led by Cornelis F. Vos and Sophie E. ter Hark at the Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The study included 56 patients randomly assigned to receive genetic testing-guided antidepressant choice and 55 patients who received treatment as usual (antidepressant choice guided by clinical judgment). All patients received tricyclic antidepressants.

The research was led by Cornelis F. Vos and Sophie E. ter Hark at the Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The study included 56 patients randomly assigned to receive genetic testing-guided antidepressant choice and 55 patients who received treatment as usual (antidepressant choice guided by clinical judgment). All patients received tricyclic antidepressants.

In the genetic testing group, the researchers assessed the patients’ CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and determined the starting dose of antidepressants based on these findings.

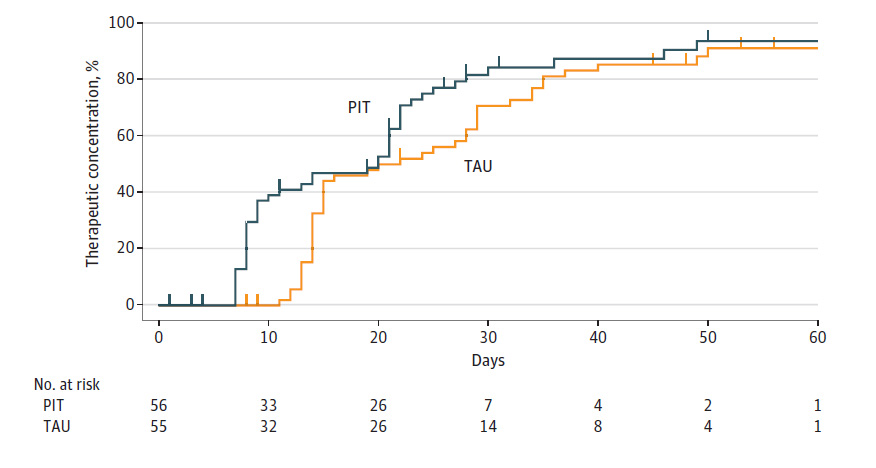

According to the researchers, the primary outcome was whether genetic testing helped the drugs reach “therapeutic plasma concentrations.” They found that about 80% of both groups attained this level. However, those who received a drug guided by genetic testing did reach therapeutic plasma concentrations more quickly: after 17 days rather than 22 days, on average.

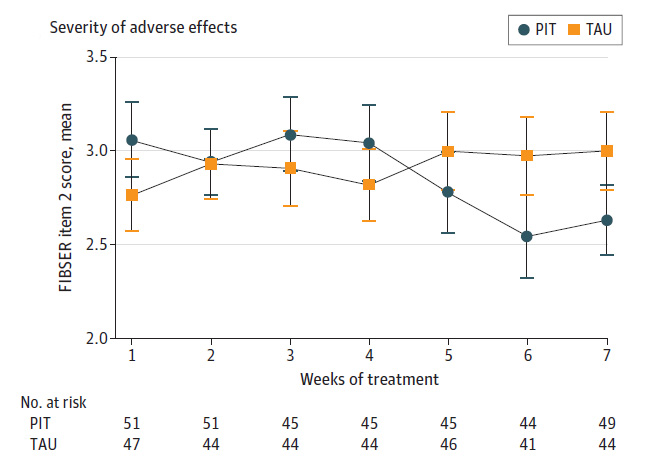

The other outcomes assessed by the researchers were changes in depressive symptoms and adverse effects. The researchers found that genetic testing doesn’t increase the likelihood that the drugs work, with both groups experiencing low response rates. Likewise, the researchers found no difference in adverse effects, on average.

However, they suggest that their study supports the idea that genetic testing can help reduce the harmful side effects of the drugs over time.

In the first four weeks of antidepressant use, those who had antidepressants chosen via genetic testing had more severe adverse effects from the drugs. However, in weeks 5 through 7, those who had genetic testing had less severe side effects. Thus, the researchers conclude that choosing a drug based on genetic testing may reduce the length of time people experience harmful side effects (or reduce the severity over time). However, as the study ended after seven weeks, we can’t see if this pattern holds true for more than those three final weeks.

In sum, the study showed that personalized treatment based on genetic testing did not lead to more improvement in depressive symptoms or fewer harmful effects on average but that there was a potential signal for reduced severity of side effects over time. In addition, the number of people responding to antidepressants was far lower than would be expected, even if the subjects had received a placebo.

What conclusion should we draw from this? The researchers write that their study was a success:

“These findings indicate that pharmacogenetics-informed dosing of tricyclic antidepressants can be safely applied and contributes to personalized antidepressant treatment.”

****

Vos, C. F., ter Hark, S. E., Schellekens, A. F. A., Spijker, J., van der Meij, A., Grotenhuis, A. J., . . . & Janzing, J. G. E. (2023). Effectiveness of genotype-specific tricyclic antidepressant dosing in patients with major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 6(5), e2312443. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.12443 (Link)

It seems like someone could make a lot of money running clinical trials that show a company’s products work better than antidepressants to relieve depression.

Report comment

Apparently, regular trips to the gym or outdoor walks already meet that standard!

Report comment

Thank you for posting this article that makes clear that the study’s official conclusion doesn’t fit the discussion of the results. How do authors get away with that?

I would welcome more discussion of different uses of gene testing.

Not all genetic testing is the same. The different panels on the market for psychiatric use test different genes and for different objectives. I would like to see additional articles on such matters.

Regarding Depression: Reference to one gene test that has been found helpful is discussed below.

I welcome any news of improved medical screening in the psychiatric setting because of the medical neglect that both of my daughters suffered, and because it has long been known and discussed in the literature that admission to a psychiatric ward delays medical diagnosis. It is especially wrong to use toxic disabling drugs as First Line Treatment, when so many medical problems cause psychiatric problems and need to be discovered and treated.

One useful gene test screens for an easily treatable medical condition that causes symptoms of depression; it tests for the patient’s ability to efficiently metabolize folate. Symptoms that are common to both that particular medical condition ( lower conversion rate of folate) and to depression may improve with the use of the supplement L-methyl folate, which is said to be useful as either monotherapy or as an adjunct to an anti-depressant. Obviously, if the patient is not getting better on an anti-depressant, but is in danger of withdrawal symptoms from hasty discontinuation of that useless and risky drug, it seems reasonable and prudent to add on the L-methyl folate which is something that your body naturally and adequately makes when all goes well.

We were interested in genetic testing for the purpose of reducing harm. Doctors ignored the results and forced the use of the worst drug anyway, to the horror of all of us.

Report comment

And this is how genetic testing COULD be helpful. Instead of testing for ONE GENE that creates ALL cases of “depression,” we should be testing for genes that explain a SMALL PART of the cohort which can actually be “treated” at its cause! Such discoveries will remove a certain number of sufferers, while not raising the belief or expectation that some magical one-gene solution will mean EVERYONE suddenly gets better!

Report comment

This is junk science. A 7 week trial! That shows nothing, really. And the authors’ conclusions contradict the discussion of their data.

Report comment