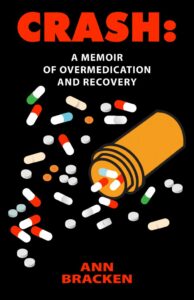

Crash: A Memoir of Overmedication and Recovery (Charing Cross Press, 2022) by Ann Bracken

It sneaks up on you—depression, overmedication, and just depressed and overmedicated author of Crash Ann Bracken was by the time she realized that depression was the least of her worries. One minute, the reader is immersed in an isolated world of a terrified child whose mother never “comes back” from “mental illness” and the treatment she endured for decades. The next minute, the reader’s heart pounds, his or her head swims, and breath catches in his or her chest right along with Bracken’s. When did Ann’s migraine start? How many medications is she taking? How long has her husband been speaking to her like that? Why does every one of Bracken’s doctors sound the same?

It sneaks up on you—depression, overmedication, and just depressed and overmedicated author of Crash Ann Bracken was by the time she realized that depression was the least of her worries. One minute, the reader is immersed in an isolated world of a terrified child whose mother never “comes back” from “mental illness” and the treatment she endured for decades. The next minute, the reader’s heart pounds, his or her head swims, and breath catches in his or her chest right along with Bracken’s. When did Ann’s migraine start? How many medications is she taking? How long has her husband been speaking to her like that? Why does every one of Bracken’s doctors sound the same?

Why does every one of her doctors sound the same indeed—including the fact that not one of them asked her about her relationships (or anything else about her environment) before they adjusted (usually increased) her medication both in terms of dosage and variety. Bracken weaves together research on the harmful side effects, known since at least the 1970s, of psychotropic medication, especially the interactions of multiple psych meds, with her personal experience of some of these exact harms as well as finally understanding what she as a child witnessed of her mother’s experience of these harms. Her portrayal of herself as a dutiful, compliant patient in order to avoid the harshest treatments but also because she at one point trusted her doctors implicitly (as many do) makes the length of time she was in an abusive marriage all the more heartbreaking.

The demands of the mental health industry for its “patients” to be compliant is still an unfamiliar feature to many. I’ve talked to more people in mental and emotional distress in the last few months than I have in the few years before the pandemic, and nearly all of them have seriously considered checking themselves into a hospital for relief—and not even as a last resort. None of them had any concept of just how severe the expectation would be to conform to whatever “wellness” looked like to the “treatment” providers, to say nothing of the major rights violations, dehumanizing treatment, mandatory medication, and other mainstays that have scarred so many psychiatric survivors. The people I’ve talked to that were considering voluntary commitment saw the hospital not even as a lesser of all options but as an overall healing place that would benefit them. Most of them are still under the impression that, if they check themselves in voluntarily, then they are able to engage in any of the “services” a psychiatric ward provides and that they are free to leave at any time.

This is very often not the case because, once you enter a psych ward, you are basically assumed to be incompetent and therefore, when you leave and what you’ll do for the duration you’re there are not up to you. Hospitals are incentivized by insurance and a medical system that loses money if people get healthy and don’t depend on it anymore, so they are interested in maximizing a person’s stay for the cashflow from reimbursements rather than for their well-being. This is stating the obvious for the veterans of the psychiatric system, but most of this is still not common knowledge.

The mistrust of doctors has been growing the last few decades, especially in the last three years. But, even as an increasing number of people are seeking alternatives to the Western medical model, it is still largely taboo to question a whitecoat about their recommendation of psych meds, as if these pills are sacred or something. And it makes sense: everyone who is not a doctor repeats the refrain “don’t start or stop medications without talking to your doctor,” in concert with the mantra that “it’s okay” to “need” medication oozing out of society’s pores. It is important to start or stop medication under the guidance of a doctor but emphasizing this without qualifications—like what philosophy the doctor has about “mental illness,” for example—seems to have led people to the conclusion that doctors are to be worshipped rather than the more appropriate one, which is that psych meds are dangerous substances.

Bracken portrays this fear of crossing doctors in mental health matters aptly in Crash; she notes just how widespread the practice is of correlating the level of “illness” with willingness to comply. This is a dangerous amount of power to give doctors, not just because it bestows the ability to force harmful chemicals down the throat of anyone they deem to “need” them (if a “patient” pushes back or even asks questions it’s construed by mainstream doctors as simply a demonstration of the need for said chemicals). It also allows those who are at best ignorant and indoctrinated (because they were trained by pharmaceutical companies; more below) and at worst intentionally seeking more power for themselves to define reality.

This is probably one reason “mental illnesses” have “skyrocketed” since (and even before) the pandemic: Big Pharma, aka companies who seek ever-increasing markets for their products that cause the very symptoms they claim to “treat” (and more!), has been allowed to define what “mental” and physical illness is for decades—even more so with the release of the DSM 5 in May of 2013. “Mental illness” is now defined by the market needs of criminal cartels that rely on force, intimidation, and deceit for their business practices. And they’ve trained an unwitting army of “mental health professionals” as well as medical/health care workers, advocates, current patients and “allies” to perpetuate their narratives.

The myth of the chemical imbalance theory even showed up in a Christian lay-counselor training I was in recently: during our unit on depression and suicide, the trainer extolled the benefits of SSRIs—of course using a personal story to emphasize the effectiveness of the medications without even giving lip service to the proven fact that every human being’s biochemistry is different, just as (and maybe even because) everyone’s life experience is different. He recited the same line that many “mental health advocates” repeat: “Just like a diabetic needs insulin, there’s no shame in needing antidepressants if you’re experiencing depression.” This is not the article to discuss whether insulin is actually an appropriate treatment for type 2 diabetes, but it’s important to note, since it’s the most commonly used analogy for promoting the use of psych meds as a “treatment” for “mental illness,” that there is actually some—growing yet suppressed—question about the line of thinking that type 2 diabetics “need” (or should be given) insulin, so in that way, then, perhaps it is an apt metaphor. The conflation of mental illness with physical illness is a stronghold in this culture, and it’s the bedrock of Big Pharma’s business plan.

Bracken tackles the chemical imbalance myth as she places the deep harm psychotropic medications do, especially in concert with other psychotropic medications, squarely in the light. In Crash, she relays the research she did about the long-known harms of psych meds as she discovered it—first with disbelief, then with confusion, then with anger, then with confidence that her doctors either didn’t know about it (or else why would they be making the recommendations they were making for her multi-med regime) or had other research to refute it. She did not suspect the immediate dismissal that her erstwhile trusted doctor gave her. When she pointed out that the list of symptoms she was experiencing were exactly the ones listed in the tomes of research she had come across about the “side effects” (as if suicidal thoughts are a mere bother off to the side) of psych meds, her doctor didn’t even ask to see these studies or ask any questions at all. He simply parroted the line that too many psychiatric survivors have heard: “It’s the depression/anxiety/[insert diagnosis here] returning. That’s why you need to stay on your meds for life.”

Bracken’s doctor told her exactly that: that her brain had been damaged by depression (of course it couldn’t be the medications he was prescribing her) and she needed to stay on her antidepressants for life to keep the depression from returning. Her doctor himself was on them, and he considered living depression-free worth all the other side effects of the medications, including his potentially marriage-destroying lack of libido. This is not an extreme case: Crash is a poignant reminder that there are still so many people suffering under the biomedical model and being told that their symptoms are simply a “chemical imbalance” without environmental factors being taken into account. So many people consuming multiple kinds of medications—more for the side effects that other medications are causing than their original complaints—without having given fully informed consent. It is still shocking to read how horribly many doctors are willing to treat their patients, and how they persist in willful ignorance about the harms their prescriptions are causing. And it’s worth asking if doctors might have something like Stockholm Syndrome related to Big Pharma, just as many of the highly institutionalized “patients” that viciously attack anyone who questions the safety and efficacy of medications might.

Bracken does not explicitly call out Big Pharma, though. Doctors certainly have some culpability in this situation as it is their job to make sure they are adequately trained and properly keeping up on the latest studies, as well as the funders of those studies. But they are mostly doing what they’re trained to do; people don’t know what they don’t know. Medical schools and licensing boards have been deeply infiltrated by Big Pharma such that the pharmaceutical industry is basically writing the curriculum that future doctors have to learn well enough to pass licensing boards. To ensure that doctors don’t question the prevailing narrative of their benefactors (the drug industry), most of the bribes the pharmaceutical industry offers to prescribers are simply irresistible. No book can cover everything, but Bracken doesn’t mention Big Pharma’s tentacles and influence hardly at all in a book about overmedication. Big Pharma has taken an even more prominent role in molding our culture, demanding conformity and breaking up families if individuals don’t go along with the dominant narrative. Even “mental health advocacy” groups default to encouraging people to not stop taking their meds and pushing for increased access to mental health “services,” which nearly always means increased access to medication with lip service to therapy.

The other curious aspect of Crash is that Bracken never identifies as a psychiatric survivor. She’d “qualify” to be considered one, but, to stay aligned with the movement’s principles, it’s vital that people self-identify as a psychiatric survivor. I don’t personally know Bracken so I can only hazard a guess, which would be that perhaps she believes that the root cause of her “mental illness” was not genetics, though her mom faced depression so severe that she was overmedicated for probably the rest of her life despite Bracken’s efforts to stop that. It wasn’t a brain-chemistry imbalance, either. It was, in fact, the 28 years of slow-release abuse in her marriage. Once she came to terms with needing to end her marriage and went through the process of doing that—not without pain itself—she was free from the mental and emotional suffering that her doctors had prolonged for years not just by overmedicating her, but by not bothering to ask about things like her relationships, career satisfaction, and other environmental factors that obviously play a huge role in a person’s well-being but are still rarely brought up in mainstream mental health “treatment.”

Though Bracken did not challenge Big Pharma (instead focusing on doctors’ complicity) and did not mention the accomplice role many mental health “advocacy” organizations have perhaps unwittingly taken on, her story is a powerful, heartbreaking wake-up call about how the severely damaging effects of medications that claim to relieve suffering can threaten generations in a family. It’s an essential voice in the puzzle of mental and emotional distress that demands more of doctors, calls for us to stop compartmentalizing human beings and reminds us that we are only as healthy as our environments. Unless we’re taking psych meds—then, we’re probably a whole lot worse off than we could be. And doctors know or should know that by now.

Hi Megan,

Thanks so much for your positive and insightful review of Crash. I’m glad that you found the book worthwhile and want to take the time to answer your critiques about not calling out Pharma and not identifying as a psychiatric survivor, though I certainly do.

As a writer, I’m sure you understand that we all make decisions about what to include and what to focus on in a work. At the time I wrote the book, I felt like it would be unwieldy for me to take on the role of Pharma, though I am certainly aware of how they push drugs on all of us and have a stranglehold on medical education. What got me to write the book was hearing Sam Quinones, author of Dreamland, talk about the opioid epidemic and how doctors had told patients they’d never become addicted–or at least only 1% of them might……When I heard that, I realized I’d been smack in the middle of the whole story because that’s exactly what happened to me.

I chose instead to tell the intertwining story of my mother and myself and how we were both treated for chronic pain and depression in much the same way–dismissed and over-drugged–even though our experiences were 30 years apart. I felt that if I could show that and show how the drugs most likely influenced the course of my mother’s inability to recover, and then paired Mom’s story with mine, people would more clearly see that the drugs are the problem. Along with our highly medicalized and decontextualized view of so-called mental illness.

While I don’t explicitly say I am a psychiatric survivor, I think that message came through loud and clear in the ways I expose how harmful Mom’s and my treatments were. It is my hope that people who read the book and are not in the world of MIA and other critical sources will begin to question their treatments, do some research, and above all, stop doing what isn’t working.

The hospital where I spent a week as an inpatient is directly across the street from me. See the poem “A Therapeutic Environment” linked below for my experience of visiting a friend there. It was terrifying to cross the threshold into the awful ward that had not changed in 17 years. I also linked the poem “The Hopkins Doctor Diagnoses Me” to show the power of psychiatry.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2020/01/hopkins-doctor-diagnoses-me-ann-bracken/

https://www.madinamerica.com/2018/05/therapeutic-environment-ann-bracken/

I have also written two pieces for the MIA family page and have linked one below where I talk about the importance of parental rights to informed consent when it comes to care for their children. I find it unconscionable that any psych drugs are given to young people and speak out whenever I get the chance–mostly to my friends and relatives if they are open.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2023/04/qa-what-is-informed-consent-and-what-should-i-know-to-help-my-child/

One last word about being a psych survivor—-It took 19 years for the feelings of terror and fear to arise after the two car crashes I endured while heavily drugged. Now that the feelings have finally surfaced, I struggle to drive on expressways and have to use a weighted blanket, CBT techniques, and herbals like Rescue Remedy to drive across town to see my daughter. I also did EMDR which helped a great deal. All of that because two doctors never took the time to look deeper into my situation and chose to drug me with opioids and benzos instead.

Lastly, about my awful marriage. I wanted to show how the long-term effects of mean teasing can be so harmful to a person. I never knew I was being abused and dated many men who teased me in mean ways and then said I couldn’t take a joke–though not anymore! That behavior from men in my circle was completely normalized. I’ve done whatever I can to break the destructive pattern for my own children, but I see verbal abuse rippling through my extended family and many of my relatives’ relationships. To reframe what happened to me, I actually see my experience of chronic pain and depression as a gift to get me out of a very painful marriage. I’ve had a second chance to make a good life and I’m very grateful. I also don’t have any more feelings of depression!

Thank you again for your thoughtful reading of Crash. I’ve read much of your other work and appreciate seeing you here on Mad in America.

All the best,

Ann

Report comment

In Mexico in the 90s it was common knowledge among physicians that opioids, even newer ones then and benzos were very addictive. Opiods were not prescribed outside terminal conditions. Rarely in low doses for no more than 5 days for acute conditions…

It was kinda cultural to avoid them.

Report comment

Yes, and the research I did showed that it was well known here in the US as well. But the story that Purdue told over and over about the drugs not being addictive somehow persuaded doctors that rule no longer held. Even if one doesn’t become addicted–which I did not, I think because the drugs never took away my headache pain–one can suffer from the harmful effects. In my case, I fell asleep at every stoplight and eventually had two car crashes that woke me up and pointed me into a new direction.

Report comment

Wow, sorry…

Around the end of the 90s I was there in the US a few years and they did have a more casual attitude towards opioids. But, you did the research :).

So I guess opioids for headaches was after 2006?

Report comment

No, my doctor prescribed opioids from 1996 to 2000. I’m so grateful that I’m ok.

Report comment

I haven’t read the book, but as it is presented in this article… It sounds like a much needed voice on an under talked about issue.

I too went down this rabbit hole of decades of over medicated “care”. As well as a very long list of psychiatric diagnosis that are on my permanent health record. It entailed a decade of me being chemically, mentally and emotionally confined to my couch and home… Unable to be an effective parent to my children.

Worse, when my son was 3 and having severe emotional and behavioral problems, my psychiatrist recommended a pediatric psychiatrist and he was put on some of the same medications as me…at 3 years old.

Since I was following my dr.s orders.. I couldn’t see that much of his problem was an ineffective mother and believed them when they said he inherited my genes.

My son suffered greatly.

At 18 years old, he took himself off the medications and never spoke to another psychiatrist…and he got better. I was inspired to take myself off the medications and never spoke to another psychiatrist…and I got better.

Thank you both for presenting this.

Report comment

Hi Ann

I especially liked your focus on the physicians. Patients and the public want to believe that their doctors are well meaning, and it seems as if doctors are excused from their role in perpetrating psychiatric abuse. Often psychiatric survivors describe their abusing psychiatrist as compassionate or doing the best they can. It was so refreshing to read a realistic portrayal of the hypocrisy and profit motives of psychiatry.

Report comment

Hi Ceceila, thanks for commenting. I’m very sorry to hear that both you and your son endured years of drugging. In reading your story, it was no surprise that your son would have behavior problems. Why do shrinks alway s neglect to look at the family ecosystem? I’m not sure what the answer is, but I’m pretty sure neither of us would ever consult a shrink again. All the best to you!

Report comment

In psychiatry no one wants to ask what happens to the patient ten , fifteen or twenty down the line after decades of compliance what happens to the patient. They don’t want to find out because they have poor outcomes!

Report comment

I bought the book. I am still reading.

I had the headache (as did my mother).

Everyday for 12 years. It went away when I passed through menopause (as did my mother’s)

I am drug free, these days.

So far … I think the book is very brave.

I can not explain my behavior on psyche drugs. That was an altered state.

I was not suicidal before the drugs and I am not suicidal after the drugs.

I told them I wasn’t sad. They said it was “clinical depression” (a bunch of malarkey).

I did give it some thought how my mother experienced her headache in the context of being a 50’s housewife (married), while I experienced it as a first generation feminist (I had to work). This gave me some perspective on how the same human condition gets experienced during different periods of history (and will be different 100 years from now)

I have abandoned the why’s of what is now long ago in my personal history.

It is a well worn caricature of a woman.

I remain curious though – why did it not kill me? (when this medical guessing game they play has killed others) How did I survive? (when others didn’t). Why did I survive? Unknown.

Part of the problem may lie in the use of that word “compliance”. It means “obedient”. There is no way under the sun, as a living creature, I can knowingly be obedient to some stranger in a white coat, who is instructing me to swallow a substance that I believe harms me. Neither their insistence that they know what’s best for me, nor my insistence that those substances harm me – can be proven. The ultimate “he said, she said”.

I recall, from early on in my ordeal – it felt like I had been knocked down and I could not get up. This was bizarre (I am extraordinarily good at getting back up). But in hindsight – that was the whole point – sedate that complaining woman!

No wonder no one gets well! (or I guess some people think they do)

I only have one regret in life, and that is that I ever spoke with a “doctor”. Someone should really teach those people how to say “I don’t know”.

Report comment

Muchos médicos son narcisistas. Y la industria farmacéutica es su propia psicopatía.

Report comment