Editor’s Note: Over the next several months, Mad in America is publishing a serialized version of Peter Gøtzsche’s book, Critical Psychiatry Textbook. In this blog, he discusses withdrawal and how to taper off psychiatric drugs. Each Monday, a new section of the book is published, and all chapters are archived here.

Psychiatrists and other doctors know very little about abstinence symptoms, which they mainly reject, and about how to taper off psychiatric drugs safely.135 One should never start psychiatric drug treatment without having a tapering plan, but no one taught doctors how to stop the drugs, whereas they have learned from their professors and the pharmaceutical industry when to start them and always to blame the disease for untoward symptoms, ignoring the troubles they have caused.

It is much easier to renew a prescription than to stop an addictive drug, and it generates a much greater income, as more patients can be seen in a day.

Patients who want to stop drugs are mostly left to fend for themselves and they share their experiences on the Internet and on social media. This is the reason why I thought it might be valuable to write a book about why and how to withdraw psychiatric drugs.8 Volunteers found the book so important that they translated it into Spanish, French and Portuguese. It is available in these languages on my website, scientificfreedom.dk, and has also appeared in print in English,8 Danish, Swedish, Dutch and Italian.

Patients who want to stop drugs are mostly left to fend for themselves and they share their experiences on the Internet and on social media. This is the reason why I thought it might be valuable to write a book about why and how to withdraw psychiatric drugs.8 Volunteers found the book so important that they translated it into Spanish, French and Portuguese. It is available in these languages on my website, scientificfreedom.dk, and has also appeared in print in English,8 Danish, Swedish, Dutch and Italian.

Few people can taper off the drugs themselves, and psychiatrists may feel disrespected when patients ask to come off the drugs they have instituted. A common notice in hospital patients’ charts is: “The patient doesn’t want drugs. Discharged.” It is therefore often psychologists, other therapists, pharmacists, friends and relatives that help patients come off their drugs.

Most patients are unable to judge themselves because the drugs have changed their brains. When in the midst of painful psychiatric drug withdrawal, their brain is in a state of drug-induced crisis and it is truer than ever that they cannot believe what their mind tells them. Patients will usually feel they are themselves and will try to explain away their odd behaviour if confronted with it. They will often totally deny that they have become irritable, agitated, hostile or difficult in other ways and will react with anger over such “accusations.”21,135

This is one of the reasons it is so essential that patients are not alone, but that close relatives or friends can observe them carefully. It can be dangerous if the patient’s false explanations are accepted. The patient should therefore allow friends and family to contact the therapist if they are concerned.135 When patients have left suicide notes, only very rarely is there any indication that the drug was the problem; patients don’t know this and think they have gone mad.7:79

It often requires strong determination, a lot of time, patience, and a long tapering period to come off the drugs while making the abstinence symptoms bearable. It can usually be done within a few months but can take more than a year. Psychiatrist Jens Frydenlund has told me that his record is eight years for an SSRI. He has worked with drug addicts for decades, and, like other psychiatrists who have experience with both legal and illegal drugs,135 he says that it is generally much easier to stop heroin than to stop a benzodiazepine or an SSRI because the abstinence symptoms with heroin disappear rather quickly.

What we need more than anything else in psychiatry are withdrawal clinics, with easy and quick access free of charge, and education about the harmful effects of psychiatric drugs, how to stop them, and above all: How to avoid starting them. Public investment in such clinics would be highly profitable and beneficial in terms of fewer disability pensions, fewer suicides and other drug deaths, much healthier citizens, and fewer serious crimes.

Nurses, psychologists, social workers, teachers and other non-prescribing people have often been taught that their task is to push people to get a diagnosis and to comply with the prescribed medication. They should be taught the opposite, that psychiatric diagnoses should be avoided and that drugs should be used for as short a time as possible and preferably not at all.

Patients don’t care about the academic wordplays whose only purpose is to allow the drug companies to continue intoxicating whole populations with mind-altering drugs. The patients know when they are dependent; they don’t need a psychiatrist’s approval that their experience is real, and some say the withdrawal from a depression pill was worse than their depression.608

The patients have been fooled by their doctors who were fooled by their leaders who were fooled by the drug industry. A recent survey of 1829 New Zealanders who were on depression pills showed that only 1% had been told anything about withdrawal effects or addiction.609

Progress is very slow. In 2020, the UK mental health charity Mind said it signposted people to street drug charities to help them withdraw from depression pills because of the lack of available alternatives. A voiceover said on BBC about this initiative: “Although they are not addictive, they can lead to dependency issues.” What’s the difference?

In November 2019, the Danish National Board of Health issued a guideline about depression pills to family doctors that was dangerous. As I knew from experience that it doesn’t lead anywhere to complain to the authorities, I published my criticism in a newspaper article.195 The Board of Health was given the opportunity to respond but declined—a sign of the arrogance at the top of our institutions related to important public health issues. They won’t admit they got it wrong.

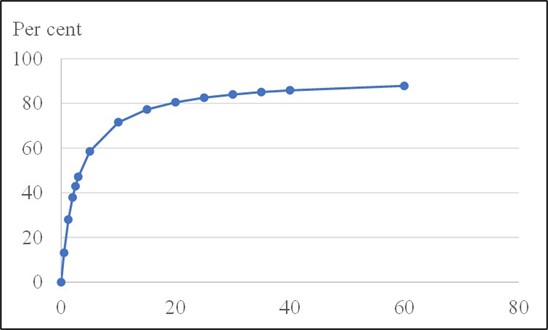

Although the author group for the guideline included a psychiatrist and a clinical pharmacologist, they didn’t seem to know what a binding curve for depression pills to receptors looks like (see graph).

Hyperbolic relationship between receptor occupancy and dose of citalopram in mg

(Courtesy of Mark Horowitz281)

As with other medicines, the binding curve is hyperbolic. It is very steep in the beginning when the dose is low, and flattens out and becomes almost horizontal at higher doses.281,610

It is important to be familiar with these issues. With my Danish colleagues, who have with-drawn many patients, I have written repeatedly about the principles in Danish newspapers and elsewhere since 2017. It is therefore strange that the board recommends halving the dose of depression pills every two weeks, which is far too risky.

At usual dosages, most receptors are occupied because we are at the top of the binding curve where it is flat. Since virtually all patients are overdosed, they might remain on the flat part of the binding curve after the first dose reduction and not experience any withdrawal symptoms. It could therefore be okay to halve the dose the first time. But even this might cause problems because psychiatric drugs are nonspecific and influence more than one type of receptor.281 We don’t know the binding curves for all these receptors. The patient could be on the steep part of the curve for one of the receptors at the start, or on the steep part in particular regions of the brain.

Already the next time, when going from 50% of the starting dose to 25%, things can go wrong. Should the withdrawal symptoms not occur this time either, they will almost certainly come when you take the next step and come down to 12.5%.

It is also too fast for many patients to change the dose every two weeks. The physical dependence can be so pronounced that it takes many months or years to fully withdraw from the pills.

As noted earlier, fast withdrawal can cause akathisia, which predisposes to suicide, violence, and homicide.

A withdrawal process must respect the shape of the binding curve, and become slower and slower, the lower the dose. These principles have been known for many years and were explained in an instructive paper in Lancet Psychiatry in March 2019,281 eight months before the Danish National Board of Health published its dangerous guideline.

After decades of inaction and denial,7 some progress is now being made. I co-founded Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry in 2014 and, as noted earlier, I was immediately attacked by the top of British psychiatry.302 I requested and was granted an opportunity to publish a rebuttal of their nonsense.311 The Council was established at a meeting in the House of Lords by filmmaker and entrepreneur Luke Montagu who had suffered horribly from withdrawal symptoms for many years after he came off his psychiatric drugs,8:97 and he wanted to highlight their harms.

After setting up the Council, Luke founded the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Prescribed Drug Dependence (APPG), which successfully lobbied the British Government to recognise the issue. He also succeeded to get support from the British Medical Association and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. That led to a ground-breaking review by Public Health England with several key recommendations, including a national 24-hour helpline and withdrawal support services.310 These recommendations do not only focus on the traditional culprits, opiates and benzodiazepines, but also on depression pills.

In December 2019, the APPG and the Council published the 112-page Guidance for Psychological Therapists: Enabling Conversations with Clients Taking or Withdrawing from Prescribed Psychiatric Drugs.611 This guide is very detailed and useful, both in relation to the individual drugs and in terms of the guidance offered to therapists.

In 2016, I co-founded the International Institute for Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal (iipdw.org), originally based in Sweden, now in the UK.

I have not had success with Danish parliamentarians. Although they were always positive when I explained why major changes are needed in psychiatry, they are afraid of going against the psychiatrists who are quick to tell them that psychiatry is outside their area of expertise.

Mind, the most influential organisation for psychiatric patients in Denmark, wasn’t forthcoming either. When I tried to get an advertisement in their member journal in 2017 for a withdrawal course I planned for psychiatrists, patients and others, they refused to accept my ad.8:99 But after I went to their headquarters with a documentary film crew, they felt pressured to give in to my reasonable request, which was in their members’ interest.

When I informed Psychiatry in the Capital Region about our course, Poul Videbech complained about to the Patient Safety Authority, which did not react to his complaint until five months later when we had already held the course. They noted they did not intend to take any action.

By the end of 2017, psychiatrist Jan Vestergaard tried to get a two-hour symposium about drug withdrawal on the programme for the annual meeting of the Danish Psychiatric Association in 2018. Even though the meeting lasted four days, with parallel sessions, the board declared there wasn’t room for the symposium. Vestergaard had asked me to speak at his meeting and I did not accept this censorship. I booked a room at the conference hotel and held a two-hour symposium for the psychiatrists in the morning, which we repeated in the afternoon. I mentioned in the ad in the Journal of the Danish Medical Association that several psychiatrists had urged us to hold a course on withdrawal of psychiatric drugs at the same time as their annual meeting.

My PhD student on the subject, Anders Sørensen,607 also lectured. Later, when we strolled around in the corridors, we learned that young psychiatrists had been scared away from attending because their bosses would see them as heretics and might retaliate, but the room was pretty full, nonetheless.

On other occasions, psychologists, social workers, and nurses who wished to attend my lectures or courses have told me similar stories about receiving dire warnings from their superiors that if they showed up, it would not be well received at their department. This is diagnostic for a sick specialty. It tells a story of a guild that behaves more like a religious sect than a scientific discipline because in science, we are always keen to listen to new research results and other points of view, which make us all wiser.

The Cochrane Collaboration, which I co-founded in 1993, was also uncollaborative.8:106 Anders and I had submitted a protocol for a Cochrane review of studies of withdrawal of depression pills, but the editors sabotaged it. The Cochrane depression group sent us on a two-year mission that was impossible to accomplish, raising their demands to our protocol to absurd levels with many irrelevant requirements, including demands of inserting marketing messages about the wonders that depression pills can accomplish, according to psychiatric dogma. Cochrane did its utmost to defend the psychiatric guild, its many false beliefs, and the drug industry, forgetting that its mission is to help patients.

It was bizarre. In the midst of all our troubles, Anders wrote to me that our review was quite simple, as we just wanted to help people wishing to come off their drugs but weren’t allowed to do so: “What kind of world is this?”

The 8th and final reviewer functioned as hangman. He denied a long array of scientific facts and used strawman arguments accusing us of things we had never claimed. We were accused of “painting a picture” about avoiding depression pills, which did not represent the scientific consensus.

The reviewer wanted us to “Start with a statement as to why antidepressants are considered by the scientific community to be beneficial … in treating a broad range of highly disabling and debilitating mental health problems” and accused us of being unscientific because we had not mentioned the beneficial effects. We responded that our review was not an advertisement for the drugs and that it was not relevant to discuss their effect in a review about stopping using them. Furthermore, a Cochrane review should not be a consensus report.

The editors also asked us to write about the benefits and to mention that “some antidepressants may be more effective than others”, with reference to the fatally flawed 2018 network meta-analysis in Lancet by Andrea Cipriani and colleagues (see Chapter 8, Part Thirteen).271

A Cochrane editor asked us to describe how depression pills work and what the differences are between them, and a reviewer wanted us to explain when it was appropriate and inappropriate to use depression pills. But we were not writing a textbook in clinical pharmacology, we were just trying to help the patients come off their drugs.

We wrote in our protocol that “Some patients refer to the discredited hypothesis about a chemical imbalance in their brain being the cause of their disorder and therefore also the reason for not daring to stop.” The hangman, who believed in the chemical imbalance nonsense, opined that we dismissed many decades of evidence of neurochemical changes observed in depression and accused us of having suggested with no evidence that prescribers perpetuate untruths to justify drug prescription. He also wanted us to mention ongoing prophylactic depression pill treatment, “a well-accepted clinical strategy,” which was outside the scope of our review. Moreover, all the maintenance studies are flawed. We were wrongly accused of having conflated relapse with withdrawal symptoms, and the hangman argued that most people who had taken depression pills for extended periods could stop safely without problems, which is blatantly false.

He also wanted us to remove this sentence: “the patients’ condition is best described as drug dependence” referring to the DSM-IV drug dependence criteria. We replied that, according to these criteria, no one who smokes 20 cigarettes every day is dependent on cigarettes.

The level of denial, obfuscation, confusion and censorship was so high that I saw this as one of several signs of the impending death of Cochrane as an organisation.146

We will publish our review in a journal whose editors are not morally and scientifically corrupt and who have the patients’ interests at heart. We uploaded all 8 peer reviews, our comments to them, and our final protocol, as part of an article we published about the affair in 2020.612

The psychiatrists and other doctors have made hundreds of millions of people dependent on psychiatric drugs and yet have done virtually nothing to find out how to help them come off them again. They have carried out tens of thousands of drug trials but only a handful of studies about safe withdrawal.

Many psychiatrists continue to turn a blind eye to the disaster they have created and argue that we need more evidence from randomised trials, but such evidence is unlikely to be helpful, as withdrawal is a highly individual and varying process. Furthermore, isn’t over 150 years of waiting enough? There has been no good evidence base either about how to come off opium, morphine, bromides and barbiturates.

I shall not repeat the extensive advice I gave in another book about drug withdrawal,8:93 only repeat a few things and add some more.

The patient needs a support person during withdrawal. It is rare that such a person can be a doctor, as most doctors expose their patients to cold turkey withdrawal and then conclude that the patients still need the drugs. But it is a good idea to inform the usual doctor that a withdrawal is about to start and hopefully get the doctor interested in helping out. Automatic renewal of prescriptions over the phone should not occur, as the risk is that drug treatment will continue for many years.

The patient should try to find a person who has succeeded with withdrawal, a recovery mentor, and involve that person in the withdrawal.

Psychologists can be very helpful. It can be overwhelming when the emotions, which have been suppressed for so long, come back, and in this phase, it can be crucial to get psychological support to handle the transition from living emotionally numbed to living a full life.

A health professional or recovery mentor will rarely be able to support a patient on a daily basis. Other support people are needed, which can be relatives or friends.

It is often huge work to help a patient get through withdrawal, and it doesn’t end there. The support person should wrap it all up together with the patient and summarise the withdrawal process, including the most important symptoms experienced along the way. The patient should be offered continued support, as there is a risk that the patient would want to come back on the drug if a situation is stressful, which can cause some of the withdrawal symptoms to return, even long after a successful withdrawal. It can take many years before the brain becomes normal again.

The patient needs to know that the support person will always be available, and the feeling of security and that someone cares can have a strong healing effect.

One should not try to taper off a patient who doesn’t have a genuine wish of becoming drug-free. It is unlikely to work. But this should not be used as an excuse for doing nothing. We need to explain to the patients that long-term treatment is very harmful and we should try to persuade the patients to start a withdrawal process.

With three experienced colleagues, I have written a short guide to psychiatric drug withdrawal, with tips about how to divide tablets and capsules. We also made an abstinence chart that allows the patient to follow the symptoms over time, and I have provided a list of people willing to help with withdrawal and links to videos of our lectures on withdrawal.613 There are many websites set up by psychiatric survivors8:198 that offer good guidance, e.g. theinnercompass.org, created by Laura Delano who lost 14 years to psychiatry7:298 but reclaimed her life after she had read Whitaker’s famous book, Anatomy of an Epidemic.5

In Holland, former patient Peter Groot and psychiatrist professor Jim van Os have taken a remarkable initiative. A Dutch pharmacy produces tapering strips, with smaller and smaller doses of the drug, making it easier to withdraw. Their results are also remarkable. In a group of 895 patients on depression pills, 62% had previously tried to withdraw without success, and 49% of them had experienced severe withdrawal symptoms (7 on a scale 1 to 7).614 After a median of only 56 days, 71% of the 895 patients had come off their drug.

Each strip covers 28 days and patients can use one or more strips to regulate the dose reduction. There is a website dedicated to this, taperingstrip.org. People in other countries currently try to convince pharmacies to produce tapering strips.

It is important to get a successful start. It is often best to remove the most recently started drug,135 as withdrawal gets harder the longer the patient has been on a drug.135,614 It is also important to withdraw psychosis pills and lithium early on, as they cause many harms.135 Withdrawal can cause sleeping problems, which is a good reason to remove sleep aids last.

It is not advisable to withdraw more than one drug at a time, as it makes it difficult to find out which drug causes the withdrawal symptoms.

It is rarely a good idea to substitute one drug for another, even if the new drug has a longer half-life in the body and would be expected to be easier to work with. Some doctors do this, but a switch can lead to additional withdrawal problems because the two drugs may not target the same receptors, or to overdosing, as it is hard to know which doses should be used for the two drugs in the transition phase. But it may be necessary, e.g. if the tablet or capsule cannot be split.

It is generally not advisable to introduce a new drug, e.g. a sleeping pill if the withdrawal symptoms make sleep difficult. It is better to increase the dose a little.

The dose reduction must follow a hyperbolic curve. This means that you reduce the dose every time you taper by removing the same percentage of your previous dose. If you reduce the dose by 20% each time, and you have come down to 50%, you should remove 20% again next time, which means that you now come down to 40% of the starting dose.

One layperson withdrawal community found that the least disruptive taper is when you reduce the dose by 5-10% per month,615 but I would not recommend this approach. If you reduce by 10% per month, it will take two years before you come down to 8% of your starting dose, so if you are on four drugs, it may take you eight years to become medicine-free. And the longer you take a drug, the greater the risk of permanent brain damage, and the harder it is to come off it.

The last small step can be the worst, not only because of physical issues but for psychological reasons. The patient may ask himself: “I have taken this pill for so long; dare I take the last small step? Who am I when I don’t take the pill?” The doctor may laugh and tell the patient that it’s impossible to have withdrawal symptoms when the dose is so low.616 If that doctor is involved in the withdrawal and behaves like a “know-it-all” guy, the patient should find another doctor.

Citalopram is recommended to be used at dosages of 20 or 40 mg daily, and it will surprise any doctor to know that even at a dose as low as 0.4 mg, 10% of the serotonin receptors are still being occupied.281 This means that the patient might experience withdrawal symptoms when going from that small dose to nothing. Psychiatrist Mark Horowitz admitted that if the patients had come to him before he had experienced the withdrawal symptoms himself, he would probably not have believed them when they said how difficult it was coming off a depression pill.616

***

To see the list of all references cited, click here.

If you are right, it’s like a story: a few Aesculapius-alike or similar humans battling millions of Fausts.

Report comment

“We were accused of ‘painting a picture’ about avoiding depression pills, which did not represent the scientific consensus.”

Oh no, blame that on me (all distress caused by 9/11/2001 was already blamed on a “chemical imbalance” in my brain alone, by my former psychologist, when I was picking up her medical records). And I painted a whole bunch of pictures visually documenting psychiatry’s iatrogenic illness creation system, their iatrogenic “bipolar” epidemic, via various historical art forms.

My artwork is now so “too truthful” it turns American Lutheran psychologists – who want to “maintain the status quo” (the “pedophile empire”) – into God complexed attempted thieves, according to a thievery contract I refused to sign.

My loved one is now on 300mg of lithium. He seemed okay, when I visited him this afternoon, but my mom said he called her this evening, and he was not doing well. His psychiatrist knows I don’t want him on the anticholinergic drugs, since my family doesn’t respond well to them.

God help us in my loved one’s healing journey, and please say a prayer for us, if you are a believer. If I can some day help my loved one wean off the lithium, should I assume a hyperbolic withdrawal of lithium is also the best way? There’s a dearth of information on the internet regarding withdrawal from lithium.

Report comment

By the way, thank you for all your truth telling and activism, Dr. Peter. It is so very important!

Report comment

Thank you so much for this critical information, Dr. Gotzsche and MIA.

I just got a case today in which the patient had no idea he was on an SNRI antidepressant (Cymbalta) because it was given for pain, along with gabapentin. I can’t fathom how many people are in the same situation. Opioids have become so demonized and difficult to prescribe in the US and now people are given drugs that are even worse (in different ways) and have no warning or knowledge of the dangers.

Frying pan into the fire…

Report comment

Perhaps the approval process for psychiatric medication should require clinical trials that demonstrate whether or not the medicine can be successfully discontinued. If no successful withdrawal plan can be clinically demonstrated, at least would-be patients would understand they are to be medicated for life and could give real informed consent to such medication.

To the extent that receptor binding is hyperbolic as suggested here, it should also be mandatory for psychiatric medicines to be made available in very low doses to accommodate tapering.

Report comment

Would you have to taper off Lexapro after taking 5mg once a day, for almost 2 weeks? What’s considered long term when taking anti-depressants?

Thank you.

Report comment

Grundbog i psykiatri (2017) Simonsen & Møhl, p 657:

This danish book for psychiatrist repeat the same mistake that you write above. They recommend stepping Down every 1/2 year, with 20% reduction of the psychofarmaka. They write following: “ved forsøgsvis udtrapning af antipsykotisk medicinering, efter længerevarende behandling, bør dette ske langsomt (fx. 20% dosisreduktion hvert halve år).” I’ve seen the consequenses of medication in practice. It is heartbreaking. I don’t wish to be ‘a know it all’ guy. But I wish to understand why this happens over and over again. It is a crime

Report comment