Pop culture, media, books, and research shape our perception of truth through master narratives or dominant storytelling. In American culture, the master narrative of resiliency often paints a heroic figure who, despite the odds, overcame adversity and ended up on top. This ability to “bounce back” from adversity often serves as a source of inspiration and is praised in American culture. However, applauding individual resiliency often overlooks racist, patriarchal, and capitalistic structures that require people to be resilient in the first place.

A recent article in press with the American Psychologist addresses issues with traditional conceptions of resiliency in psychological research. It then suggests a way forward that redefines narratives and centers the identities and experiences of Black, Indigenous, and LGBTQ+ individuals and communities.

In efforts to have a strength-based approach to the study of adversity and trauma, psychology and other allied disciplines incorporate concepts of resiliency into their work. For instance, when examining the impact internalized homophobia has on LGBTQ+ mental health outcomes, researchers also highlight LGBTQ+ community connectedness as a powerful protective factor in overcoming adversity.

Although this preferable approach moves beyond traditional deficit-based frameworks, a team of psychologists led by Kate McLean, director of the LISTEN (Learning about Identity through Story Telling and Engaging with Narratives) Lab, argue that a “structural-psychological approach” to resiliency will improve strength based frameworks. This framework moves beyond the narrow and dominant focus of individual experience to account for broader socio-political context and historical factors that uphold systems of inequality and impact individual functioning.

The team writes:

“The hyper-focus on the individual in theory, design, and measurement promotes a story about resilience that hinges on individual responsibility and blames people for their poor choices without attention to the lack of choice that structural entities impose.”

They “argue for a redefinition of resilience in the context of these larger structures of inequity and oppression and the cultural and historical forces that continually shape them.”

Examples include using race and socioeconomic status as variables without recognizing racism and capitalism.

They explain that researchers, industries, and academic disciplines (like psychology) that fail to link individual functioning to macro structures are complicit in creating and using “harmful master narratives about resilience.

This is seen “in the form of publications, funding, and intervention efforts paid to concepts like grit and growth mindset, in which children of color and poor children, for example, are expected to overcome the “odds” of racism and poverty by developing individual strengths.”

The question, they argue, “is not whether children can (or should) nurture a growth mindset, but why we collectively invest so much attention and resources in a story about individual-level skill sets rather than a story about the sociohistorical context that created the need for these interventions in the first place.”

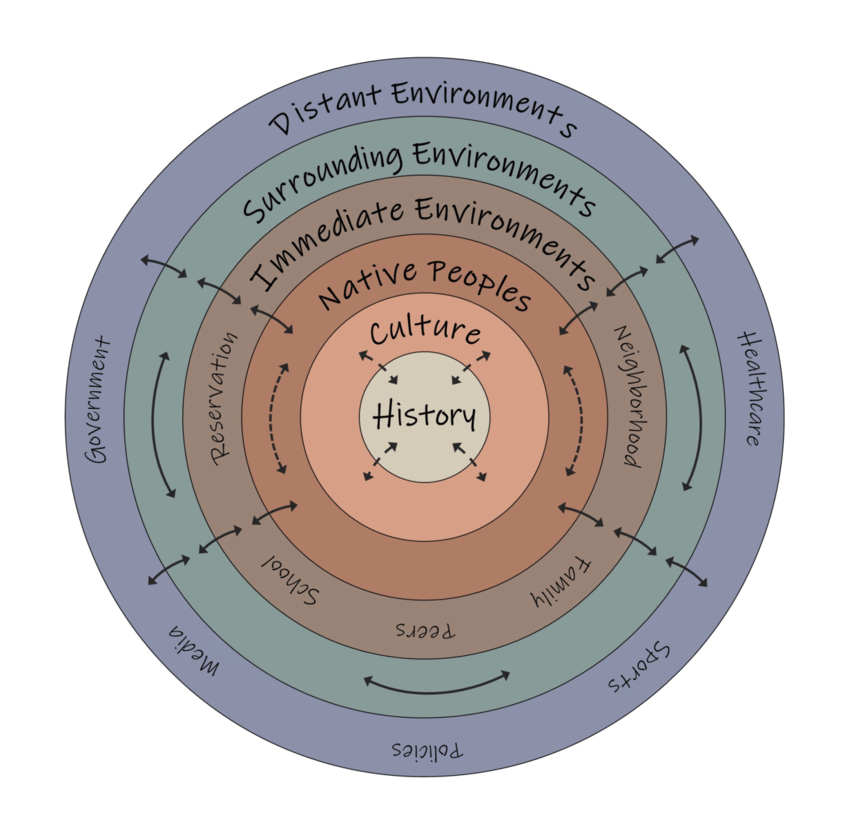

The researchers argue against Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model, the traditional model used in psychological research to understand resiliency. They then draw on scholarship that has rightfully centered the voices of marginalized groups to uplift the “Indigenist Ecological Systems Model” and the “M(ai)cro Model” as examples of a structural-psychological approach to resiliency.

The Indigenist Ecological Systems Model

The Indigenist Ecological Systems Model

When discussing the resiliency of Indigenous communities, traditional models fail to account for the erasure of Indigenous culture and stolen land through settler colonialism. Failure to recognize the ongoing legacy of such violence perpetuates harmful master narratives of resiliency and makes efforts to raise awareness and reduce disparities fall short. They use the following example to explain:

“It is impossible to facilitate Native peoples’ resilience and reduce educational disparities without reckoning with the legacy of boarding schools and the trauma of violently assimilating children by stripping their bodies and minds of their culture (e.g., language, clothing) – settler colonial practices still present in higher education.”

Furthermore, traditional models make false assumptions about protective factors contributing to resiliency. For example, in contrast to what traditional models imply, for Indigenous peoples, extended ancestry and access to culture and history are central to health and well-being.

The M(ai)cro Model

Traditional models include larger social contexts that shape individual experience (e.g., legal and educational systems) but wrongfully fail to acknowledge systems of power that organize the functioning of these systems. Drawing again on the example of educational disparities, the researchers write:

“To examine school belongingness for children of color without integrating the racist structures that were designed to disadvantage them and advantage white children, such as segregation and tracking, leaves any attempt at understanding academic resilience or addressing educational disparities severely flawed.”

Advocating for the M(ai)cro Model, the researchers urge scholars to see the individual and the structure as inseparable and shaped by larger power structures.

In sum, “a structural, psychological perspective is one that centers the societal systems of power, oppression, and marginality while respecting the individual-level capacity of all humans to resist, transform, and thrive.”

By using this approach, master narratives of resiliency, which glorify individual triumph, can be replaced with narratives of resistance. Narratives of resistance value the collective resistance communities have in the face of adversity. Furthermore, they value how unique identities navigate systems of oppression and simultaneously acknowledge power, inequality, and socio-political and historical contexts that require communities to be resilient in the first place.

These models and critiques are a first step. They can and should be adapted and extended to create additional models for other communities facing ongoing marginalization via systems of oppression.

****

McLean, K. C., Fish, J., Rogers, L. O., & Syed, M. (2023). Integrating Systems of Power and Privilege in the Study of Resilience [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/yhmj9 (Link)

In the context of oppressive systems, Resilience means replacing screams of pain and tears of vulnerability with a bitter, sardonic sneer.

Report comment

People used to say mind over matter. But either way it’s bullshit.

Report comment