In the first essay of this three-part series, I noted that current estimates of the incidence of antidepressant withdrawal range from 1% to 50%; and that patients’ beliefs and hopes, and the availability of alternative treatments, influence how they hear explanations of antidepressant risk.

Now let’s think about where and when patients hear those explanations. Most often it will be just before a prescription is written, in a discussion of “Procedures, Alternatives and Risks”—the PAR conference, as physicians learn it in medical school. The PAR is supposed to present benefits and risks for each of the treatment alternatives a patient might consider. But the PAR process is more complicated than you might think.

Benefits: Managing the Placebo Effect

Antidepressants, on average, add a small increment of improvement over what a placebo offers. For example, in one review, placebo reduced depression symptoms by half or more by an average of 35-40%. For antidepressants, that average was only slightly higher: 42-53%. These results suggest that, on average, most of the value of an antidepressant is coming from its placebo value. After all, we do call these medications “anti-depressants”, right? Perfect.

This is so important, here’s one more striking example. In a study of patients with migraine headache, patients were aware that they might receive a placebo or an anti-migraine medication called Maxalt. Those who were given a placebo but who were told that it was Maxalt had more pain reduction than those who were given Maxalt but told it was a placebo. Even those who were given a placebo and told it was a placebo had a substantial reduction in pain compared to those who received no treatment.

Think about what this means for providers who are trying to offer a patient accurate information about an antidepressant. They know that the patient may indeed choose to take it, so they try to maximize antidepressant’s placebo value. The prescriber must somehow describe a small-to-medium potential benefit and a substantial array of risks, including risk of severe withdrawal symptoms, without undermining the patient’s belief that the pills could help. In other words, even if the antidepressant itself doesn’t directly contribute much, the placebo benefit can be substantial—unless the prescriber has sown doubt in the patient’s mind while trying to be transparent about what can be expected.

You see? Two goals are in direct conflict here: fully informed consent versus maximizing placebo value. An effective prescriber must actively balance these two goals.

Risks: The Nocebo Effect

On the flipside lies similar PAR challenge: patients deserve an accurate account of risk. But too much emphasis on a treatment’s potential risks can increase expectation of those potential problems and thus increase the experience of them (a “nocebo effect”). For example, in a review of trials of COVID-19 vaccine trials, people in the placebo groups had nearly as many adverse effects (headache, fatigue, nausea, muscle pain) as people in the active vaccine group, but only with the first dose. With the second dose, adverse effects were far higher in the vaccine group, presumably because vaccine was indeed inducing an immune response leading to those symptoms, while the placebo group, having weathered the first dose, had lower expectations for problems.

Therefore, an effective prescriber must convey information about antidepressants’ risks without creating too strong an expectation for such problems. It’s just like the balancing act required to maximize placebo value, but in reverse: in this case, minimizing expectations while conveying accurate information.

Further, there are a lot of side effects and risks to consider. Offering a litany of all known concerns would be too lengthy: substantial risks could be overshadowed by the long list of little ones. Instead, the prescriber chooses which risks to present. Generally, this includes any risks that are dangerous, and any that are extremely common. (In addition, I often present the risks that a patient is likely to run into on the internet with even a simple search. I’d rather they hear about these risks from me, where I can shape how they sound.)

Thus, in the PAR process, two goals are in direct conflict: fully informed consent versus maximizing the medication’s value. I hope this is starting to sound nearly impossible to you. In the face of this challenge, I suspect prescribers likely tip this complex balancing act toward the treatment they think is most likely to help their patient. (Decreasing patient autonomy, but from benevolent motivation.) This means the prescribers’ beliefs about benefits and risks have a very strong impact on how a treatment is described.

Prescribers Are Human Too

Humans use shortcuts to estimate risks, especially in conditions of uncertainty. These shortcuts are often wildly inaccurate. For example, the “availability” shortcut: if an example of a particular event comes quickly to mind, we think the event is common; whereas if an example is hard to find in memory, we think the event is rare. This obviously leads to errors when the event is striking and dramatic (e.g. a terrorist attack) or off one’s radar (e.g. treatment-resistant tuberculosis).

Imagine how this affects a clinician’s thinking. If one of their patients recently had a great response to a particular antidepressant, then if they’re like most humans, the clinician will evaluate the benefits of that antidepressant more positively than if it’s been a long time since seeing such a response. Likewise, if they haven’t recently seen a patient have significant withdrawal symptoms (perhaps because their patient left and never told them about it; or perhaps because they didn’t ask), then if they’re like most humans, the clinician will evaluate the risk of antidepressants with less concern than if they saw a recent severe case.

In other words, prescribers are subject to common cognitive errors (patients too). These include confirmation bias (more likely to hear and see results that support one’s previous beliefs); the well-traveled road effect (a repeatedly used tool, such as an antidepressant, is more likely to be used again); and many others.

Too Many Options

Prescribers also fear that if they presented the entire menu of options, they’d be sitting with the patient for many minutes, explaining each treatment and its pros and cons. Some of the treatment options for depression are quite complicated: transcranial magnetic stimulation, for example; or how to use a light box correctly. The clinician might regard some treatment options as ill-suited to that particular patient: ketamine, for example, in a patient with bipolar disorder (because research has only just recently been expanded to include bipolar depression). Thus, prescribers narrow the range of options considered, focusing on those they think are most likely to help. Here, the balancing act is self-preservation, if you will, versus patient autonomy.

The Process Is Actually Backwards

Thus… while attempting to balance information to maximize placebo value and minimize nocebo effects; and while being human (subject to cognitive biases, error-prone mental shortcuts, and desiring self-preservation); in actual practice, the consideration of Procedures, Alternatives and Risks occurs in reverse: the prescriber decides what one or two treatments might be best and then presents those alternatives to the patient. Maybe three. Only rarely would the full smorgasbord be offered. In other words, the decision-making begins with the provider, not the patient.

To partially reverse this sequence of events in favor of greater patient involvement, multiple groups have advocated a process referred to as Shared Decision-Making (SDM) (including Britain’s National Health Service, in their most recent guidelines.

Shared Decision-Making

SDM doesn’t necessarily mean sharing the entire smorgasbord of treatment options, although that’s one way to start. It means sharing the decision-making process after disclosing the risks and benefits of at least a few treatment options. Unfortunately, although treatment results are better when patients are involved in decision-making, healthcare professionals do not easily adopt SDM and even institutional efforts to make it routine have often failed. One of the reasons: creating informative Patient Decision Aids (PDAs) is difficult.

Patient Decision Aids

PDAs are supposed to help providers share treatment decision-making, including paper or video or digital educational materials focused on a specific health problem. They aim to empower patients by presenting information in an understandable manner, hopefully decreasing confusion about options and helping make sure that treatments selected truly align with patients’ preferences and values. But in practice, they haven’t become common. Here are two reasons why.

First: PDAs are like the consensus statements from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: for matters of controversy (e.g. whether to say “phase out” or “phase down” fossil fuels”), PDAs tend to present the most conservative views.

Perhaps that’s why so few PDAs about depression say anything about antidepressant withdrawal: it’s too controversial? In one of the largest PDA libraries available, there are seven PDAs on depression. How many of them address antidepressant withdrawal? Just one, and only if you count this description: “Quitting your medicine all at once can make you feel sick, as if you had the flu (headache, dizziness, light-headedness, nausea or anxiety.”

Secondly, providers are hesitant to use PDAs because they interfere with the sensitive and complex process I just described: balancing the need for information transparency with the need to maximize a treatment’s value by maximizing patient confidence in whatever treatment they choose. Even a well-balanced, conservative PDA could tilt a patient away from a treatment that could be very helpful for them. So rather than start from a generic presentation of the full smorgasbord of treatment options, clinicians tend to focus on a few, presenting those options in the best possible light.

Unfortunately, this leaves the PAR vulnerable to the profound influence the pharmaceutical industry has had, and continues to have, on clinicians’ concepts of “best options”. In particular, the entire concept of “FDA-approved” treatments is an egregious twist of public trust: since companies must have FDA approval to market a new product, and the only way to get such approval is to run randomized trials that cost millions of dollars, only new expensive drugs can earn FDA approval. Generic drugs do not because there is no financial incentive to run the necessary large trials. Thus, new drugs are loudly touted as “FDA approved”, which obviously suggests, even without stating it as such, that all the other treatments patients might consider are “not approved”, which certainly sounds like “disapproved”. Not the right starting point for creating a good placebo effect.

The pharmaceutical industry has many other means of influencing clinicians’ concepts of “best options”: attractive, personable “reps” make office visits, with samples alone a sufficient inducement (which many clinicians use to allow a few patients access to a new treatment they cannot otherwise afford). So, no question, “pharma” has strong influence. Some clinicians work actively against this influence: no office visits for reps, no samples, staying skeptical about industry influence on published articles, presuming that randomized trials are slanted in favor of the company’s drug (especially if they sponsored the study), waiting for broad clinical experience (not company publications) to show that a new medication really gets better results than inexpensive generics, and believing that only long experience will reveal the true risks. Granted, not all clinicians are thus cautious.

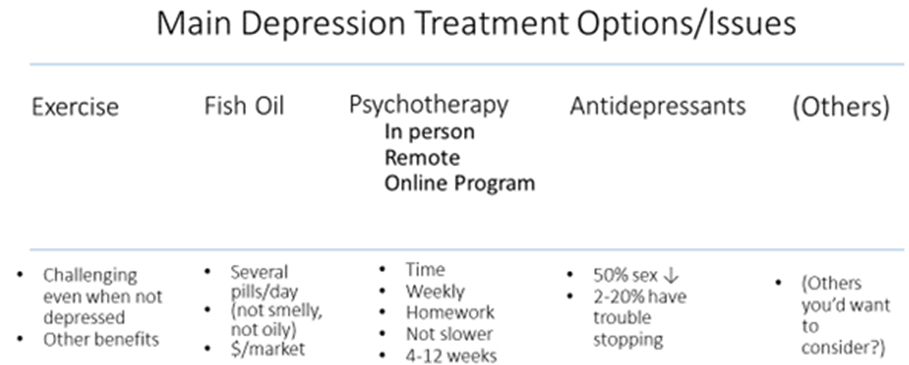

To avoid clinician-narrowing of options, moving too quickly to antidepressants and offering only a choice of which antidepressant to take, here’s a broad PDA. It’s just a first draft, because the next step in developing PDAs is to seek input from users: patients and providers. Then revise, and revise again—hopefully not becoming so watered down in seeking consensus that no one wants to use it!

Just as an example, then:

I used “2-20% have trouble stopping”. That’s an example of consensus seeking. If it elicits equal criticism—too low and too high—then perhaps it’s about right for now, until we have more data.

Conclusion

By examining placebo effects, nocebo effects, and recognizing the inevitable effects of patients’ and providers’ beliefs and biases, I hope to have convinced you that a balanced PAR is difficult, but not entirely impossible. However, imagine doing this in a busy primary care practice, where most antidepressants are started. Tried to get an appointment lately? Tried to find a new PCP lately?

Otherwise, I don’t have great solutions to offer. Why write all this, then? Two reasons: first, I hope to show readers that there are important reasons why the risk of antidepressant withdrawal has not been well explained to people before they start them. These reasons must be considered by anyone who wishes to change the way antidepressants are prescribed.

Secondly, I have a hunch to share. What if we could identify in advance the patients who will have severe withdrawal problems? They could be given much stronger warnings about this risk. And if they’re already on an antidepressant, they could be given careful tapering instructions about taking slow small steps down.

In the last of these three essays, I’ll describe my hunch and suggest some of its implications.

So much about why withdrawal in particular has been left out of provider-service user conversations is missing from this piece (one major factor being the complete lack of belief in service users). PAR is but one aspect in a very large ecosystem of responsibility and accountability. Additionally there are real themes of ethics but merely touched on here that open into the larger conversation about the actual clinical efficacy of these drugs in the first place, about whether or not we should be even using them at all. The political and economic influences on this system are not addressed either. There is so much missing here from a piece aimed to address some sort of middle ground on this issue. It seems that major factors of influence have not been taken into consideration. Also, for a significant percentage of service users there is no informed consent at all, in any way, and often there isn’t even more than 1 option of treatment suggested. I feel like this article was written in a foundation of an alternate reality instead of within the context of what the system actually looks like, and how it functions.

Report comment

Laura, thanks for your comment. I agree.

Report comment

It’s not so hard to figure out: He obviously has a hard time picturing himself NOT writing prescriptions.

Report comment

Many of these comments from multiple c ommentators sound hostile and angry and personally critical of the author. As a 40-year user of antidepressants (raised to dislike and avoid any medication). I was astonished. After many, many efforts to control my severe deoression–including electroshock therapy–I finally found a combination of drugs that brought me into complete remission, a place I have been for 5 years now. I am convinced that the cause of my depression is chemical. I also exercise, get enough rest, socialize, care for my grandchildren, and am learning to play the piano at age 75. I wish we once again lived in a world where civil discourse is the rule.

Report comment

You don’t speak for everyone.

Report comment

We’re you told “you have borderline personality disorder. That’s why the ECT didn’t work?”. We’re you abused in psych wards?

Have you been subjected to ongoing attacks based on being “a borderline”? Many of those attacks came from “professionals.”

This author is proposing that lying to patients is fine. Some of us object to being lied to. Some of us consider lying to patients malpractice.

I wish we lived in a world where survivors of psychiatric abuse didn’t have to live in fear.

Report comment

I wish we didn’t live in a world where “my life is fine. I’m not homeless. I’m not alone. I feel good about psychiatry therefore everyone else should too and should stay silent about the ways they were harmed because I’m fine” wasn’t yet another way to silence people who are suffering.

Report comment

Hearing different points of view is just too much for some people.

Report comment

“I am convinced that the cause of my depression is chemical. I also exercise, get enough rest, socialize, care for my grandchildren, and am learning to play the piano at age 75.”

Why mention the things you do if you’re convinced that your depression is chemical? It sounds like you just want to let the angry and hostile commentators know that they’re defective and should feel shame, that no one cares how they feel and that they don’t deserve any support in dealing with broken lives post-psychiatric hell. These are messages I receive every single day, so if this is your message it is redundant. I am shamed, blamed and ostracized on a daily basis. There is no help. No one cares. Most people I encounter are like you: extremely judgemental, okay with the rampant abuses of the health care system. Sorry that I’m not one of those upstanding citizens who doesn’t mind that doctors lie. Sorry I don’t enjoy the same privilege that you do. Congratulations, you made me cry.

Report comment

I care about you very much, KateL.

Report comment

I’m so sorry that you’ve been harmed so much by this system, KateL. Your comments resonate. You deserve so much better. We all do, even the ones who don’t realize it. Meds always stop working, and then you’re left with the frightening realization that they didn’t actually make anything better, they just jacked your brain and made you detached.

Report comment

The purpose of the MAD website is to highlight what happens long term to patients put on these toxic CNS drugs over the long term-particularly to those put on complex polypharmacy regimens. The answer is clear! Very poor long term outcomes and harm.

Report comment

Some of the pieces on here are notorious for that.

Report comment

My goodness! Don’t you think everyone should have their say?

Report comment

Thank you, Birdsong.

I guess some people don’t understand the terror of being sick from withdrawal, alone, unable to do basic tasks, no support services, no medical care, no family, no transportation, no emergency contact…slowly dying alone… while some professional goes on and on about how what psychiatry does isn’t evil capitalist torture and somebody thinks that if they don’t have all these problems and they’re learning to play the piano it’s because they’re morally superior somehow.

I’ll be glad when it’s finally over.

Report comment

You’re most welcome, KateL.

I think one of the hardest things in life is learning how to not let someone’s smug, insensitive remarks get to me. Which is hard to do because sometimes there seems to be so many smug and insensitive people. So most of the time I just consider the source and forget about it because it’s bound to happen again.

But whatever you do, KateL, please don’t ever let it make you give up.

Report comment

KateL, I know what it’s like to be misjudged and mistreated by medical professionals, many of whom seem to have special talent for automatically disregarding people with a psychiatric history. And a lot of other people can be pretty good at that, too. It’s totally wrong and totally cruel and shouldn’t happen to anyone, but the sad reality is the patient’s diagnosis precedes them, which is why I never share my medical history to regular people and make every effort to avoid the medical world as much as possible.

Report comment

Notorious for calling out lies and abuse?

Report comment

I actually do give up. It’s so clear that there’s no help in this world for the extreme long term trauma I live with, alone in everything and even on so called “advocacy” spaces people still gaslight, victim blame and try to silence me. Nothing is going to change. The victors are the ones who lie and blame shift and assert their smug superiority as though their privilege is a result of moral superiority. If I can’t figure everything out completely alone while being criticized and shamed and attacked then I just get kicked again and if I don’t smile about it here comes another kick in the face.

Report comment

KateL, I totally get how you feel. And no one has any business suggesting that the way you feel is in any way your fault. It’s bad enough the world’s not ready to hear the truth, and it’s not your responsibility to make people listen. I felt better when I stopped looking for support in the “medical” arena, and I’m not surprised that so many of the so-called “advocacy” spaces aren’t much better. So sometimes giving up can actually be a good thing, as long as you don’t give up on yourself.

Report comment

Clarification: It didn’t take long for me to stop looking for validation from people in the medical or “mental health” arena because most of them are trained to use DARVO (deny, attack, reverse victim and offender) in order to ward off lawsuits. But I have found a lot of comfort finally knowing who the assholes actually are, thanks to the internet.

Report comment

Oh it must be so hard to be a doctor. So so hard. So hard so very hard. Oh well, you took an oath what happened to that. Oh informed consent is so hard. It’s so very hard. It’s so very very hard. Not buying it.

Report comment

Let me guess: the ones with withdrawal issues have personality disorders.

Report comment

How do you know that any patient is harmed by the drugs? Oh that’s right, you used us all a lab rats the last 40 years.

Report comment

Exhibit A of avoid psychiatrists like the plague.

Report comment

How about an Exhibit B for psychologists?

Report comment

Wow. I find this article to be rife with hugely flawed thinking and frankly, it’s insulting. I’m not sure where to begin, nor do I have the energy to respond, so maybe someone else would like to comment.

Report comment

I can sum it up in two words: Medical Chauvinism.

Report comment

I’d bet a hundred bucks the reason that’s going to be given for why “some” patients have withdrawal is going to be another gaslighting and blaming tactic that allows the prescribers to wash their hands of the whole mess while the people in withdrawal still have no solution or hope except “figure out yourself, the corrupt system that caused this has fully abandoned you.”

Report comment

“But, Sweetie, we lied to you for your own good! Why can’t you understand that? Why can’t you see that we knew you wouldn’t be able to handle anything like “information”, or “facts”? We did the best thing for you and we’re sorry that you’re so mentally ill that you can’t see it.”

Report comment

The author’s playing politics and doesn’t even know it.

Report comment

Preach

Report comment

I will.

Report comment

🙂

Report comment

I agree, finding a just and fair middle ground would be great. But what I see is we have bad systems, where doctors are both uninformed, and misinformed, by big Pharma and psychiatry. But there is also a lack of ethics issue on the part of many doctors.

For example, none of the doctors even knew that a common withdrawal effect of the antidepressants was “brain zaps” or “brain shivers,” until 2005.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247806326_'Brain_shivers'_From_chat_room_to_clinic

That’s an example of doctors being misinformed … and highly hubris filled. But since all doctors were taught in med school about anticholinergic toxidrome – so all doctors already know that both the antidepressants and antipsychotics can create “psychosis” – via anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Yet since too many doctors tend to deny this knowledge to their clients, there is also a lack of ethics issue on the part of the doctors, who deny the commonly known adverse effects of the anticholinergic drugs.

Report comment

We get it. It is still a massive failure of informed consent.

Nocebo effect is also caused by losing trust in doctor expertise, beneficent intention, and respect for my autonomy when they don’t give needed information to make reasonable decisions and lie about how medications they prescribe work.

It really is ok to tell people that the primary effect of antidepressants is placebo, the mechanism of limited helpful drug effect is unknown, and that effect is likely related to potential issues with withdrawal to a meaningful minority of patients, more than the initial side effects that only <5% of people that are typically warned about before initiating despite the claim there isn't enough time. You will be expected to stay on these medications for months to years to indefinitely depending on your response. This can be true and you as clinician can also say that considering your symptoms, this may be a worthwhile option. It really isn't complicated and takes 8 seconds.

I really wish I had that conversation before before I started medications, instead of when I was being admonished for wanting to stop and made the mistake of assuming I ought to include my psychiatrist in that decision. I wish I never had that conversation at all. It would have helped me communicate better about my needs/experiences/fears of the medications as I took them, but may have helped me decide that my distress wasn’t bad enough to be worth the risk of taking drugs from a person undeserving of my trust, which in retrospect I believe would have served my mental health much better.

Really, if a treatment works by necessitating maximizing confidence, as if it was a confidence game, it probably shouldn’t be on offer in the first place.

Report comment

“Really, if a treatment works by necessitating maximizing confidence, as if it was a confidence game, it probably shouldn’t be on offer in the first place.”

BINGO!!!

Report comment

And mainstream medicine today, particularly psychiatry, has and is largely proven itself to be nothing more than “a confidence game,” a con, a scam

https://psychrights.org/2013/130429NIMHTransformingDiagnosis.htm

… which means the doctors have chosen to become the “evil” Pharmakia forcing “witches,” about whom the Christians were forewarned against, in the Holy Bible.

Perhaps, all doctors should think twice, prior to adopting this societal role? Thankfully, due to Covid, some decent doctors are speaking out against the “status quo.”

https://thephaser.com/2023/11/pfizer-the-covenant-with-death-dr-james-thorp/

Report comment

…and no one should be paying for placebo pills.

Report comment

This guy apparently seems to think people aren’t capable of gathering quality information on their own via the internet. And for some reason, he doesn’t seem to realize that people might actually be better off WITHOUT a doctor’s egocentrically biased salesmanship. Does he even LIVE in the 21st century???

Here’s what I think is really going on: the characteristic tendency to infantilize “patients”, along with a growing fear of becoming irrelevant in the internet age.

Report comment

Unfortunately, I think they’ve got a whole new generation young people brainwashed, judging by comments on social media.

One person said that she “needs to be on several medications, because my body doesn’t produce serotonin.”

Someone replied to her, “every body produces serotonin naturally.”

She replied, “Right…so you’re saying that my therapist and my psychiatrist both lied to me?”

Someone asked if she’d been tested for serotonin deficiency. She said, “It’s not like that. I have clinical depression and ADHD. People who have these illnesses are lacking serotonin.”

Her belief system is more the rule than the exception. I wish I’d had access to the information that’s accessible now, but I feel like there’s a strong wave of “trust your doctor” happening. I’ve tried to explain to people that what they were told is made up, but they just get angry.

Report comment

The level of defensiveness is very disturbing. And for most people there’s no talking them out of it, which I think it stems from a subconscious fear of having to face painful emotions.

Report comment

CORRECTION: The level of ignorance and defensiveness on the part of both service users and so-called “clinicians” is VERY disturbing, almost as disturbing as how eagerly the media keeps repeating psychiatry’s shameful lies.

Report comment

You’re right, though, Birdsong… the information about the devastation these drugs can cause is widely available now. We don’t have to rely on people who have a problem with informed consent.

Front page NY Times today:

After Antidepressants, a Loss of Sexuality https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/09/health/antidepressants-ssri-sexual-dysfunction.html?smid=nytcore-android-share

Report comment

If an article like that in The NY Times doesn’t make people think twice about taking so-called “antidepressants”, I don’t know what will.

Report comment

Yep, today at least people have the benefit of this info being available on the Internet… since they probably won’t get it from prescribers

Even the experts quoted in the article engage in gasli…um, denial of patient experiences.

This quote is just one example:

“I think it’s depression recurring. Until proven otherwise, that’s what it is,” said Dr. Anita Clayton, the chief of psychiatry at the University of Virginia School of Medicine and a leader of an expert group that will meet in Spain next year to formally define the condition.”

I think it’s a really clever stance, since she knows that PSSD will never be proven. She’s aware that nothing the experts study (in the areas of “mental illness” or “how psychiatric drugs work/don’t work/cause a huge number of side effects/lead to lasting damage”) has ever been proven. All they have are theories, which are usually disproven 40 years later.

So, saying, “until PSSD is proven, it’s the depression recurring” is really clever. It allows them to continue to put the responsibility on the patient indefinitely.

Report comment

Dr. Clayton’s remark jumped out at me too, but I don’t know why it did because that’s business as usual in psychiatry-land. And how much more “proof” does anyone need?

Report comment

Thank you for talking openly about the withdrawal effects of anti-depressants. I have been on and off anti-depressants for many, many years. The withdrawal effects are and can be extremely debilitating. I wish someone had informed be better as well, I wished I had listened to my own experiences and not allowed the providers to keep “pushing ” them on me. I tried to tell them and they said “you’re wrong, these kinds of withdrawals aren’t listed, you must be experiencing something else” I admittedly, believe them and I paid a tremendous price.. September 5th of this year I almost died because of these medications and the lack of provider support, both in proper medication management and general mental health support. Due to this, I will never do that to myself again and I hope our mental Healthcare system changes to be help and support each and every human being that needs and wants help. Part of the problem is over-prescribing, lack of proper patient education and a lack of care when that gets challenging or rough. It’s my personal, real life experience that thinks primary care doctors shouldn’t be prescribing anti-depressants. They arent properly trained and honestly, neither are the Psychiatrist. Anyone who knows what these medications actually and still prescribes them without full disclosure or as you put it “picks the ones, they think you should be on” should have their licenses taken away. People suffer because “you don’t have enough time”.. come on!!! There was so much BS in this article! The only thing worth talking about is the withdrawals and the incredible amount of side effects that a patient WILL encounter. Stop defending what’s wrong in the mental health world. Use your voice for the good of human beings that are being hurt. We know doctors are human too, however where’s that human when YOUR deciding my life with my limited input. We suffer, not you. I’ve had 1 doctor in all my anti-depressant journey who showed any humanity and compassion. It was after I almost died, she cried and her tears where from her heart breaking that she thought she had given me the anti-depressant that lead to that horrible day in mine and my family’s life.. we need more truth than the pretty commercials give you as “information ” this effects a human life! Anti-depressants change that for good and bad. I’m not saying anti-depressants are bad for everyone, I speak only for myself. Yet I know others struggle as well. More truthfully informed information is what we are asking for. A full picture. Believe it or not, not all patients are conservative. Sometimes the benefits can out way the risk. We need this autonomy, we need to be included in life changing decisions.

Report comment

“The prescriber must somehow describe a small-to-medium potential benefit and a substantial array of risks, including risk of severe withdrawal symptoms, without undermining the patient’s belief that the pills could help.”

The patient has an irrational belief that the drug is the answer, so the clinician must tiptoe around honest information to maintain this belief? What kind of reasoning is this? This is a clinician rationalizing why prescription of an antidepressant is necessary.

In this scenario, “maximizing the placebo effect” is an euphemism for “babying the patient along” or “keeping the patient in the dark”.

What is the point of “maximizing the placebo effect” by persuading someone to take a drug with significant risks? (Yes, 2% risk withdrawal is ludicrous and 20% is far too low. But even if the risk was as low as 20%, that’s a pretty big risk. What would you think if a surgeon told you risk of death from an operation was 20%? Makes you think twice, right?)

There is no conflict between being honest about the marginal efficacy of antidepressants and maximizing the placebo effect by talking them up. The supposed conflict can easily be resolved by — talking up a placebo! As long as you’re going to fabulate, do it with a relatively harmless drug.

Yeah, we know prescribers don’t have time to explain everything someone should know before choosing a psychiatric intervention, especially given the billows of misinformation obscuring the benefits and risks of every alternative. That’s what makes informed consent so difficult — doctors don’t actually know anything about the interventions. Taking shortcuts due to uncertainty means prescribers customizing a fiction for each patient and hoping for the best.

Report comment

“The patient has an irrational belief that a drug is the answer…”

I think the biggest problem is how most “clinicians” have an irrational belief in themselves.

Report comment

If a drug’s efficacy is so low that one could render it ineffective by accurately describing it, it seems the logical thing to do is not prescribe it. Informed consent and patient autonomy ought to take priority, both because of ethics and because the patient is better aware of their goals and values than a medical professional could ever be. Also, such minimal effects would seem to be suggestive that the medication is not actually more effective than placebo, and is simply appearing more effective due to partial de-blinding due to side effects.

Report comment

Truly a mad world – there is no such thing as an ‘antidepressant’ its purely a marketing term. I understand the regulators allow the term to be used if a drug company can show only two positive trials. What this means is a tiny none statistically meaningful reduction on the HamD. Furthermore the regulators are completely uninterested in any other prior studies that show no effect or major harm.

We all know how adept and well practised industry is at data manipulation including all out fraud attracting billions in fines, not to mention corrupting everything from peer review, funding the regulators and controlling journals.

A major issue is primary care has become a production line, doctors have indeed mainly become ‘prescribers’ time tight and massively stressed and subjected to control and manipulation by an industry clearly completely out of control and causing more harm than it can ever do good.

Am I right in thinking for example that by some estimates prescribed drugs, taken as prescribed are now the third or forth leading cause of death? no doubt they will enter pole position when we discover that prescribed drugs are also massively implicated in heart disease, stroke and respiratory illness.

Our food system is poisoned, people are sat down staring at screens all day, mind numbing body and brain harming jobs, surrounded by corporate manipulation, cut off from nature, community, meaning and purpose, in massive debts with more human beings in the UK now living in destitution and we are all witnessing our leaders driving us off the cliff. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/destitution-uk-2023

There is a long history of drugs marketed as safe and effective and it seems to take about 30 years and millions of people harmed before anything begins to change. Then its far far too late, the mindset, the harm, the system is entrenched.

Is this part of your informed consent discussion? NEXT.

Report comment

The good doctor admits that placebo outperforms antidepressants ( I assume he is referring to SSRI’s) yet had he been in any other specialty other than psychiatry such as oncology or cardiology then he and the profession would cease prescribing antidepressants since they are ineffective and there is more harm done long term than any benefit.

The Need to Treat, Need to Harm and Need to cure calculations do not apply to Psychiatry since prescribing worthless and ineffective drugs to patients is justified. For example aspirin was recommended for those at risk of stroke of cardiac events but after it was found to increase stroke risk it was reversed! There is no medical reversals in the cult known as psychiatry.

Report comment

“I suspect prescribers likely tip this complex balancing act toward the treatment they think is most likely to help their patient.”

This statement is false since guidelines for prescribing in this “profession” mandate the NEWEST drug in that class be prescribed first NOT what the one prescriber feels would be best for the patient. These so called guidelines in psychiatry are designed to cater to big Pharma and guaranteeing new drugs or new drugs that are tweeked for patent extension and guaranteed a lucrative market! The proscriber is forced to write a script for the newest and least understood drug compound.

Report comment

Given the placebo data on antidepressants, the correct interpretation is that patients with depression should be given a placebo as the first line of treatment and the doctor should maximize the benefit for the placebo.

Report comment

I wonder how employers feel when they realize how much of their healthcare expenses are actually just a placebo effect?

Report comment

So where is Jim’s voice in this dialogue. Published articles should have a codicil or requirement to at least reply once or twice. Writing is only one part of a dialogue.

Report comment

Hi Mary. Fair enough, I should say *something*. But I worried about doing harm with these essays, causing variations of anger from irritation to fury. Not healthy for anyone. I wrote them because I hoped that there might be an ear for the “middle ground”. Overall, I’d say that was an almost complete failure. So I’ve not been replying to Comments for fear of just making things worse.

I loved AltoStrata’s “There is no conflict between being honest about the marginal efficacy of antidepressants and maximizing the placebo effect by talking them up. The supposed conflict can easily be resolved by — talking up a placebo!” Indeed, that’s why fish oil appears right after exercise (which is no placebo but hard enough to do regularly even when *not* depressed).

Just as an aside which I hope might actually *be* helpful, here’s a little more info on fish oil. Most doses have about the same benefit as a placebo pill. Beating placebo requires 750mg or more of EPA, in a form at least 2/3’s EPA vs DHA, according to several analyses of randomized trials. Since EPA-rich forms *do* beat placebo, doctors can recommend “fish oil” (without necessarily specifying the harder-to-find form) without violating the ethical principle they’re supposed to follow about not prescribing placebos. Right, right, I know: some don’t follow that principle. And yes, the principle involved is fully informed consent. And yes, there are fascinating studies (e.g. as described

here… https://www.health.harvard.edu/mental-health/the-power-of-the-placebo-effect) about placebo treatments still working even when people were told they were being given a placebo.

Here’s a thought for everyone: notice that no one commented my mention of Sara Schley’s book BrainStorm, From Broken to Blessed. I’d love it if everyone who’s still reading would get a copy and read it. It’s one of the best psychiatric success stories, and illustrates what we can sometimes do that’s *good*. True, it took a lot of false starts and bad outcomes to get there. But that makes the good outcome more believable.

Anyway, thanks for your note and invitation to jump back in. I think on balance it’s best if I not try for true “dialogue”. Not because I’m deaf to the comments being made. I think I understand most of them, and the pain and frustration that lies behind them. Best not to stir that up further without something more helpful to offer, I think. Wishing you all well —

Jim Phelps

Report comment