One of the most important elements of the Szaszian worldview is that liberty and responsibility are two sides of the same coin. His writings are clear that with the liberation of the mental “patient” should come responsibility for his or her actions, reactions, productivity, failings, and crimes. This manifested most clearly in Szasz’s opposition not only to civil commitment, but to the insanity defense as well. He opposed the view of the mental “patient,” most notably the “psychotic” or “schizophrenic” one, as incapable of acting with agency (either due to “disease” or past trauma).

The insanity defense is an issue I have thought about a significant amount. Up until recently, I was weakly in favor of keeping it. Surely someone who was hallucinating a fact that caused them to commit a crime should be treated differently than one who was not, right? Should the hallucinations affect the mental state of the person performing the crime as it relates to intentionality, though, this would already be true in the criminal justice system without an insanity defense. The state of mind of the defendant would be considered in a typical criminal trial, regardless, and considered in charges, convictions, and sentencings.

It is also unclear whether defendants know what they are getting into with an insanity plea. In fact, according to Jim Gottstein of the Law Project for Psychiatric Rights, the average person found not guilty by reason of insanity is actually incarcerated for longer than they would have been had they simply gone through the justice system. They are also far more likely to be subjected to other forms of coercive psychiatric measures. (While those can happen to criminal prisoners as well, it is rarer.)

It is important to acknowledge that, should we concede that a hallucinating or delusional individual lacks agency, and cannot prevent themselves from becoming dangerous, a lot of justifications for civil commitment policies may follow from that. Individuals deemed not fully in control of themselves are controlled by others in our society to prevent damage to themselves and others. This may make sense with toddlers, but not with adults. (The extent to which this is justified for adolescents is hotly contested; I consider myself a proud supporter of youth rights and the expansion of medical capacity in general, but that is a discussion for another day.)

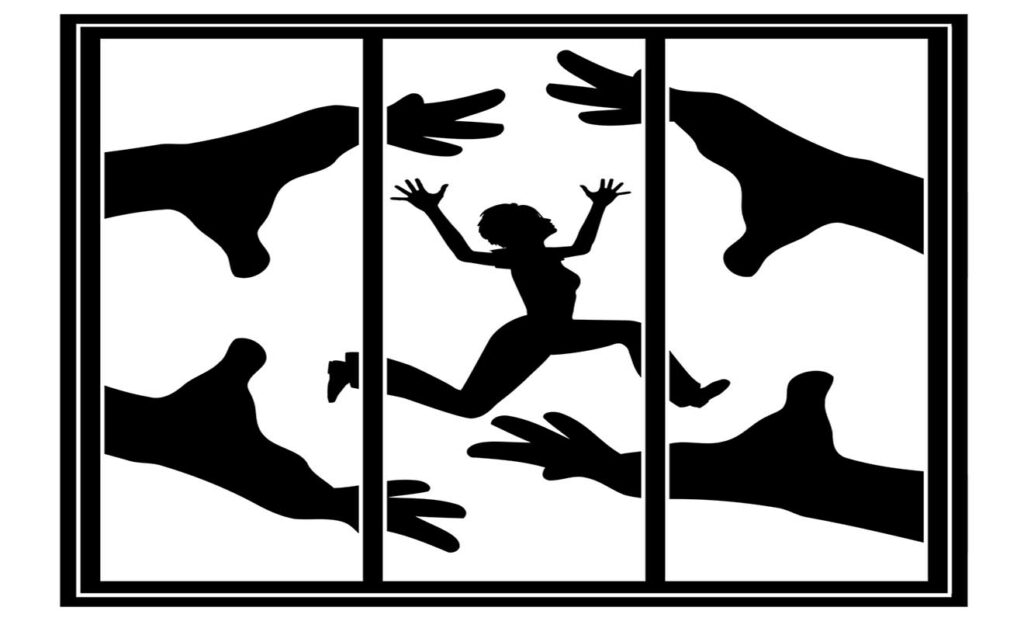

Many individuals with so-called “psychotic disorders” are deeply offended by implications that they simply cannot help themselves but to become violent. They are and always have been in full control of their actions. It is not uncommon to come across rightfully indignant comments from people who have been ascribed such psychotic labels that “Having bipolar disorder doesn’t excuse you from being a criminal!” or “Schizophrenic people aren’t inherently prone to violence!” To call violence a “symptom” of “mental health issues,” and to say that those labeled as having such “issues” cannot help themselves, is so wholly offensive that it would be unconscionable to apply to any other oppressed minority group. Yet, the “schizophrenic” or “psychotic” individual is permitted to be discriminated against and infantilized in this way.

Szasz has also been widely criticized for his portrayal of those deemed “schizophrenic” as “liars.” In hindsight, this was surely a poor choice of words on his part, especially out of context. One must look at a fuller quote to understand him better: “I believe viewing the schizophrenic as a liar would advance our understanding of schizophrenia. What does he lie about? Principally about his own anxieties, bewilderments, confusions, deficiencies and self-deception.” His choice to use the word “liar” may be seen as inflammatory, but in context, his not a fundamentally different point of view from trauma-based understandings of psychosis. In describing psychosis as a form of self-deception about uncomfortable realities, he is not invalidating the struggles themselves that the “psychotic” individual faces. Rather, he seeks to help the person develop this same insight and become better adjusted versions of themselves.

In Schizophrenia: The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry, Szasz argued that the oppressed “schizophrenic” individual ought to not only be freed not from psychiatric bondage, but “improved” upon his release. This aspect of his writing is often overlooked; he wanted to aid in the quality of life of those diagnosed with psychotic disorders beyond simply relieving them of their chains. To him, this constituted a “clearly desirable goal” to be pursued “intelligently and properly.” Rather than continuing incarceration and chemical straitjackets, he believed in common sense solutions: guiding the freed people to become competent, self-sufficient, productive members of society.

The disease-mongering psychiatrists would object to Szasz’s goals for the “schizophrenic,” stating that this is too much to expect of someone with such an “illness.” They would huff and puff that you should not expect so much of this poor, diseased individual. They would say that, despite all of the advancements of medical technology, the involuntarily declared “schizophrenic” could not yet achieve competence despite their best efforts “treating” him.

Does this align with the view of formerly incarcerated “psychotic” individuals? Well, no, at least not most of them. As with any formerly abused or tortured people, some may claim to be grateful after, to love their former oppressor. This occurs with victims of all kinds. Regardless, when it comes to those who feel they benefit from a coercive system, Szasz is not against their right to set up advance notice for psychiatric compulsion if they so want to. To him, when someone arranged for their own psychiatric incarceration or violent “treatment,” it was compatible with his vision (so long as they did not impede others’ right to resist this same compulsion). When looking at default policies, though, we cannot look to the fawning responses of a select few individuals. We must look at the views of the majority, the typical impacts on their lives, and the implications for society as a whole.

The typical coercively diagnosed and treated “schizophrenic” has a very different take from the disease-monger on their plight. Psychiatry is needlessly abusing them, violating their human rights, making them traumatized and incapacitated. The stories are coercive, violent, harrowing—yet, the psychiatrist is “helping,” simply because he says he is. Despite all this “help,” the “schizophrenic” cannot contribute normally nor make himself capacitous, and this is justification for more “treatment.” Any objections by the “schizophrenic” constitute more proof that they lack insight to know how much the psychiatrist is “helping.”

Most people diagnosed with so-called serious mental illness have the goals stated by Szasz: to be competent, employed, and functional. How many have been helped with that goal by their “helper” psychiatrists? Well, not many: that would be bad for business. One may say that cure is often less profitable than permanent customers in all of healthcare, which is of course an issue in itself. However, it is especially abhorrent when one is using manufactured diseases to torture someone into perpetual bondage, for profit, to possibly deadly ends. According to the Institute for Scientific Freedom, it has been proven in numerous studies that these “treatments,” especially “involuntary” ones—for “diseases” that are subjectively and unreliably “diagnosed”—massively shorten life spans for those using them.

Beyond coercive psychiatry, Szasz was a harsh critic of other types of oppression. Szasz’s criticisms of psychiatric bondage were what he is best known for, but he was also vehemently against misogyny and racism. He repeatedly spoke out against misogyny, for some examples in Schizophrenia: The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry and The Maternity Hospital and The Mental Hospital. He compared the oppression of women in traditional marriages and maternity wards, respectively, to the oppression of “patients” by psychiatrists. He viewed coercive marriages and childbirth practices as being unethical violations of individual freedom.

In addition, for the case of People v. Cromer, Szasz traveled thousands of miles to testify against Cromer. She was a white woman who viciously murdered a black child. Did she have a hallucination that he was attempting to attack her? No. Did she have delusions which would lead her to believe he was about to be violent? No. Was she so separated from reality as to not comprehend what she was doing? No. Her stated intention was to eat the boy to make herself more beautiful. She consciously entered into this act, knowingly causing the death of a child, for her own selfish gain. Szasz could not let her attempt to fool herself and others to believe that this murder was anything less than a conscious act of evil.

Szasz’s belief in autonomy and responsibility regardless of sex, race, or alleged mental state showed throughout his life. Were he to say that women or black people were too feeble to be considered equally before the law, this would cause great moral offense in most people now. However, as we see from history, that was unfortunately not always the case for the public. What is so obvious now as to be considered indisputable was not so in previous times. (It must be heeded that discrimination is still a very real factor for many women and black people. However, at minimum, the letter of the law and most of society have changed in a way that they have not yet for “mental patients.”)

Perhaps in the future this equality will be extended to individuals who experience altered states of consciousness, experience strong emotions, or have beliefs or lifestyles outside of the norm. Those deemed insane by society are still ardently discriminated against. Even supposedly “liberal” and “democratic” outlets portray them stereotypically, calling for what amounts to collective punishment in a manner which would never be accepted for any other group. Coercive commitment practices are an affront to the individual, international law, and human dignity.

By setting standards of equality, competence, and accountability, Szasz’s missions actually align with those for whom he truly cared. Rather than setting a warped, Kafkaesque trap of insight for clients, he advocated for their stated interests. In the future, he will be remembered as a fierce advocate for one of the most marginalized groups in American history. Though he did not believe in an afterlife, I could only hope there is some similar way for him to see that day come from beyond the grave.

I think this is a good summary of Szasz’ ideas, but I think there are critics now of conventional psychiatry that are making much more cogent criticisms. I wish someone would write something on MIA about, say, Loren Mosher, who risked, and lost, his prestigious position with NIMH because he spoke out about what he saw was wrong about the way psychiatry treated its patients. I was lucky to have been able to spend time in a place in Canada inspired by Soteria House, and it was a great help to me.

Report comment

I agree that to seperate out the insane criminalfrom the same is a mistake but the question of how we address criminality is important. I think responses always need to be flexible.

My father tried to kill my step mother, he was mad with rage but not in the technical sense insane. It would not have mattered if he was hallucinating, people needed to be safe and he needed people to watch over him and talk him down. Criminality is a problem.if communities as is madness.

Report comment

Society needs to be protected from people who’ve broken the law regardless of their agency. Whether they can regain their agency is another matter entirely.

Report comment

Society also urgently needs to be protected from self-styled “mental health professionals” who disable the brains of their trusting clients with chemical and electrical lobotomies, or who arbitrarily assign degrading labels based on the invalid “diagnoses” concocted by DSM panel members.

Report comment

As is how we help people necome responsible citizens after they have committed crimes

Report comment

What you say is true, however, psychiatry perceives its role as protecting society from people who in many cases have not broken the law. No one I think disputes that society should be protected from people who break the law regardless of agency, but with all due respect, I don’t think that is the key issue here. The key issue has to do with whether it is right to incarcerate and drug someone against their will when they have not done anything wrong. There use to be a law which says that people are innocent until they are proven guilty. This is no longer the case. In many cases, people are being pronounced guilty by psychiatry before they have done anything wrong to deserve it.

Report comment

I agree with you 100%.

I don’t think psychiatry protects people; I think it’s dangerous on many levels.

Report comment

Very good article if I do sat so myself

Report comment

Having been a good friend of Tom’s I would agree with much of your analysis. Most critics of his are not close readers of his many books. He was a very sensitive, humane, and exceptionally learned individual, a rarity in our current intellectual atmosphere. My book co-authored with my friends and colleagues, Stuart Kirk and David Cohen, Mad Science: Psychiatric Coercion, Diagnosis, and Drugs relied on much of his conceptual framework girded by the latest scientific data.

Report comment