From Investigative Journalism Foundation: “Every five weeks Kirsten Anvik takes two buses to a strip mall pharmacy in Esquimalt, B.C., to pick up 300 milligrams of an antipsychotic medication. Then, with a vial of the drug in hand, she pushes through an interior door that connects the pharmacy to a medical office and sits in the waiting area, dreading the injection to come.

A 54-year-old single mother, Kirsten — who goes by Kir — once aspired to teach yoga. But that dream vanished soon after she was prescribed Abilify Maintena. ‘My balance started going off,’ she says, ‘and I was getting nerve muscle spasms in my limbs.’ She also began to notice debilitating nerve pain, swelling throughout her body, and problems with her hips. ‘Little by little, my body started to stiffen up.’

She says that the drug has taken a toll on her mind as well, that it dulls her emotions and causes brain fog. She takes four other medications —lisdexamfetamine, pregabalin, clonazepam, and zopiclone — to minimize its effects.

Abilify Maintena is the injectable form of Abilify. Both are widely prescribed to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Their active ingredient, aripiprazole, activates dopamine receptors in the brain. Aside from its possible physical side effects — which include loss of balance, muscle pain and stiffness, inner restlessness, weight gain, seizures, and involuntary muscle contractions — aripiprazole has been linked to compulsive behaviours, such as pathological gambling, binge eating and hypersexual activity.

Despite the harm the drug can cause, and the harm Kir says she’s experiencing, the B.C. government is forcing her to take it. She isn’t allowed to stop — or to swap it out for a substitute she might better tolerate.

. . . Under B.C.’s Mental Health Act, involuntarily detained patients like Kir are not only stripped of their right to refuse treatment, they are unable to appoint a trusted friend or family member to act as a substitute decision maker.

If Kir doesn’t show up for monthly injections, she’ll set off what she calls a traumatic chain of events: her family doctor will alert her case manager, who will alert her psychiatrist, who will sign a medical warrant authorizing police to bring her to the hospital so she can be forcibly injected.

She knows well the feel of handcuffs, the startling burst of activity when the police appear. One time they came for her when she was sick, sitting in a robe on her couch, eating ice cream. She says their insistent knocking — which she describes as ‘sharp and ominous’ — made her feel instantly ill. Upon opening the door, she told a police officer she had to use the bathroom. The next thing she knew, her ice cream was in the sink and she was in handcuffs.

For a long time, Kir lived with anxiety about her provincially mandated appointments. Had she lost track of time? Had a month already passed? She’d shudder at the sight of the police. Once, when a friend spotted her in a Walmart aisle and called out her name, she froze in fear. Out of context, her friend’s voice was unrecognizable; Kir thought the police were about to swarm her.

For eight years, she has wanted nothing more than to feel well physically and to have control over all aspects of her life. ‘I’ve got these invisible shackles on me,’ she says.

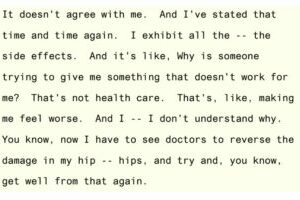

. . . Kir repeatedly has asked her psychiatrist to take her off Abilify Maintena.

‘You have a voice,’ he reminded her recently. ‘But unfortunately you don’t have a choice.'”

***

Back to Around the Web