Thanks to excellent work of Mark Horowitz and David Taylor we now have the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines for Antidepressants, Benzodiazepines, Gabapentinoids, and Z-drugs. I consider this very good news for all who want to taper withdrawal-causing prescription drugs safely, and for all who want to help them as best as they can. The new guidance offers strong and comprehensive support and will aid development of new guidelines and will help to improve existing ones. In the UK, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has already updated advice about Stopping antidepressants.

Unique in the new guidance is concrete practical advice on how to implement personalized gradual tapering schedules in which the dose is gradually reduced in multiple steps, which get smaller as the daily dose gets lower. This gives the body time after each step to adjust to a slightly lower dose, which makes withdrawal symptoms less likely to occur, or not occur at all. When withdrawal still occurs, there will be more time to do something against it. Why tapering in smaller steps works better than in large steps is obvious: the risk of destabilization after a dose reduction of for example 1 mg will be smaller than after a dose reduction of 5 or 10 mg or more.

One of the practical tools mentioned in the new Maudsley Guidance are the tapering strips I have been working on for almost 15 years. In the Netherlands, they have been prescribed to more than 20,000 patients. I receive many questions about them. Can anyone can use them? Why and how were they developed? How well do they do work? This blog gives some answers.

Can anyone use tapering strips?

In most countries it will be possible for patients to use the tapering strips, when their doctor judges that they meet their needs and no alternative is available. The new Maudsley Guidance explains that tapering strips can be prescribed off-label. The UK General Medical Council (GMC) defines off-label prescribing as the prescribing of medicines which are used outside the terms of their UK license, or that have no license for use in the UK. Unlicensed medicines are commonly used in some areas of medicine, such as psychiatry. This may be necessary when ‘there is no suitably licensed medicine that will meet the patient’s need’, when ‘the dosage specified for a licensed medicine would not meet the patient’s need’, or when ‘the patient needs a medicine in a formulation that is not specified in an applicable license’ (GMC, 2021). According to the FDA, ‘healthcare providers generally may prescribe the drug for an unapproved use when they judge that it is medically appropriate for their patient’ (FDA, 2018). This also applies to the prescribing of lower than available licensed dosages for tapering, as are being used in the tapering strips—dosages which have all been batch quality controlled and certified by the independent Laboratory of the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association.

How can tapering strips be prescribed?

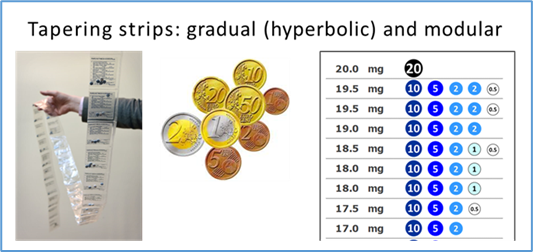

Prescribing a personalised tapering schedule when using tapering strips has been made as easy as possible. Prescriber and patient together decide on the duration, start dose and end dose of a planned taper. For the pharmacy this is enough information to work out the corresponding hyperbolic tapering schedule and to provide all the required daily dosages for it to the patient. Every daily dose is precisely determined and separately packaged in the small sackets of one or more tapering strips. An option has been created to request a free tapering recommendation. This will result in personalized tapering advice that can be used as a prescription for the chosen tapering schedule, or to choose another schedule when this is judged to be more appropriate. Tapering strips are currently available for more than 60 different prescription drugs.

Why and how were tapering strips developed?

A short history of withdrawal

To explain why tapering strips were developed I first take a short dive into the history of withdrawal. Withdrawal occurred from the very moment withdrawal-causing prescription drugs were prescribed. The first reports in the medical literature are almost 70 years old. A telling example is a randomized study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1958. In this study, significant withdrawal was observed after abrupt discontinuation of meprobamate, a sedative that was then often used for treating anxiety and insomnia. Withdrawal symptoms observed in this study were various degrees of insomnia, vomiting, tremors, muscle twitching, overt anxiety, anorexia, ataxia, hallucinosis with marked anxiety, tremors much resembling delirium tremens and grand-mal seizures. The report ends with a spot on and surprisingly modern recommendation which is completely in line with the new Maudsley Guidance: ‘that it seems wise to discontinue slowly, to prevent the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms’. In 1958.

Why was so little done to prevent withdrawal?

Over the years, countless patients have suffered from withdrawal, often with severe consequences. Why then, despite such early recognition of withdrawal, was so little done to prevent them? An explanation that is often put forward is that withdrawal was not well recognized and mistakenly interpreted as relapse. Reinstating the drug was often the quickest cure for withdrawal, strengthening the belief that staying on the drug was necessary to prevent relapse.

There is another possible explanation that sheds more light on the development of the tapering strips. This pertains to the absence of adequate tools to facilitate gradual discontinuation, which made it very difficult or impossible to follow the sensible advice in the 1958 study I mentioned. The crux of the matter lies in the necessity for dosages lower than those typically included in the limited range of standard dosages registered by the FDA. It is now generally acknowledged that much lower dosages are required than that. Without them, safe tapering of withdrawal-causing prescription drugs is difficult or simply not possible.

In light of this, it is difficult to understand why psychiatric associations and regulatory bodies like the FDA, EMA, MHRA and NICE always seem to have assumed that the available limited range of licensed dosages are adequate for most prescription drugs—with notable exceptions like insulin. Available licensed dosages allow patients to start using prescription drugs without knowing if they will be able to discontinue them later. Metaphorically speaking, this is akin to allowing pharmaceutical companies to sell cars without having to verify if they have brakes that are functioning.

Many patients understood what the problem was

Early on there were patients who understood that lower dosages were needed for safer tapering (Moore, White, Framer, Groot). As did some professionals like Prof. Heather Ashton, who developed the Ashton Manual to help patients to safely come off benzodiazepines. The work of Mark Horowitz and David Taylor, who experienced withdrawal themselves, demonstrates how important such personal experiences can be to understand and appreciate problems of withdrawal.

How patient contributions led to the development of tapering strips

In 2004 Dutch wood carver Harry Leurink proposed the making of a ‘medication withdrawal strip’: ‘A very gradual decreasing dosage of medication packaged in strips with a time sequence’. He did this after he had desperately been trying for years to come off benzodiazepines without succeeding. Each time he tried he suffered so much from withdrawal, that he was forced to start using benzos again. I have repeatedly and reproducibly experienced withdrawal myself, each time after I forgot to take the daily dose of the antidepressant venlafaxine I had been using since 2004. This started me thinking about finding ways to prevent withdrawal also. In 2012, unaware of Leurink’s idea, in the Journal of the Royal Dutch Medical Association I proposed to develop stop-packages.

A very fortunate accident

It was a very fortunate accident that emeritus professor Dick Van Bekkum, who was then already 87 years old, read the article. I very much doubt if we would have had tapering strips today if he hadn’t. Van Bekkum was founder and Chairman of the not-for-profit foundation Cinderella, which had started a project to develop Leurink’s medication withdrawal strip for the antidepressant paroxetine. The working assumption was that a strip for a limited number of days would suffice to prevent withdrawal.

This, as we now know, was a very naive assumption, but it turned out that making this assumption was a big advantage, because it was clear that it would be technically feasible to create such a single strip, which made the project less daunting and more approachable. Van Bekkum contacted me and asked if I would work with him on a voluntary basis to develop what we now call a tapering strip for paroxetine. He was very outspoken: ‘We don’t need new guidelines to be able to do something. We can make this strip and that’s what we will do. When we have it, we will see what comes next’. A decisive moment. I agreed and added venlafaxine as a second antidepressant for making a tapering strip.

A pharmacist needed to be involved

We were faced with practical problems we knew we could only solve with the help of a pharmacist who would work with us to develop the tapering strips, make them and provide them to patients. Together, we set out to find one. The second pharmacist we approached was Paul Harder of the Regenboog Pharmacy in Bavel. He was willing to work with us and had some brilliant ideas about how to make the strips. Practical problems I had foreseen vanished in thin air. Within a year, the first tapering strips for paroxetine and venlafaxine could be made available to patients.

Way too fast

A tapering strip to taper paroxetine ‘gradually’ in 28 days is better than stopping abruptly, but not good enough. A justified comment on the website Surviving Antidepressants was that ‘28 days to get off paroxetine is way too fast. It takes months or years’. This made us realize that we had to improve things, which we did by developing a modular system in which multiple tapering strips can be used to come up with any personalised tapering schedule a doctor wishes to prescribe.

After the first tapering strips became available, patients as well as doctors made clear to us that there was a greater demand for tapering strips than only for paroxetine and venlafaxine—that they were also needed for other antidepressants, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, antipsychotics, opioid painkillers, anti-epileptics and other withdrawal-causing prescription drugs.

What I learned from my own tapering experiences

I began contemplating withdrawal when I discovered that forgetting a single daily dose of venlafaxine resulted in almost immediate withdrawal. An indescribable unpleasant sensation in my head appeared, sometimes within hours, and certainly within a day. This instilled fear in me, as it resurrected old anxieties and thoughts of suicide. While these thoughts didn’t immediately render me suicidal, they alarmed me. I had been severely depressed and knew that such feelings could escalate. My father had taken his own life in 1979, and I was determined not to follow the same path.

In the beginning, I did not connect these negative feelings to withdrawal, because I forgot to take my medication only occasionally. It took quite some time before I was certain that forgetting it was the cause of my misery. Discovering this was a relief and made my life much easier, knowing that taking the missed dose would make me feel better within hours or at most one or two days.

Explaining the importance of lower dosages for tapering

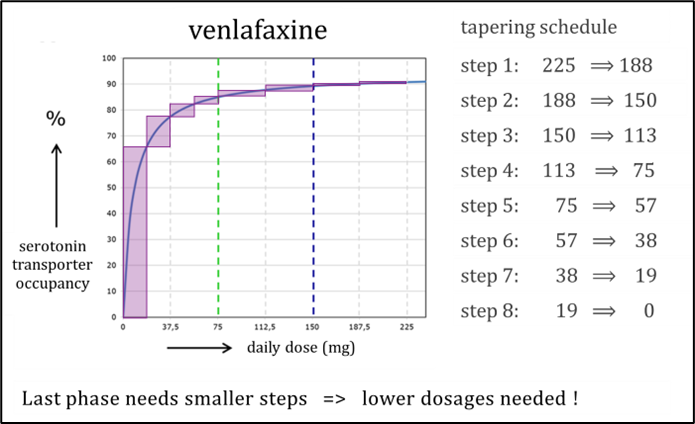

As many others before me, I came to realize that it would be necessary to make dose reductions smaller as the dose got lower. To explain this, in 2015 I came up with the picture below, which I used to make visibly clear that the last ‘small’ dose reduction of 18.75 mg of a linear taper of venlafaxine has about 3 times as large an effect on the occupation of the serotonin transporter as all 8 previous dose reductions of more than 200 mg combined.

When in 2019 Mark Horowitz and David Taylor published their landmark paper about hyperbolic tapering, I was thrilled. They gave us something to help convince the psychiatric community that safe tapering ‘is not quite like the standard texts say’, as David Taylor had put it so well already in 1999. The publication of the new Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines makes me happy again. However, first and foremost, practical solutions are needed which can readily and easily be prescribed and used right now. Theory and guidelines can come later.

Do it yourself tapering should not be necessary

It is possible to taper by for instance opening capsules, counting beads and putting them back. My own partner did this years ago, to taper the venlafaxine she had used for some time without a positive effect. She succeeded, but not without difficulty. Static electricity was a problem, coughing or a draft through an open door was a problem, lack of concentration could be a problem. I found the whole process distressing and strongly felt that it was wrong that she was forced to do this because no better options were available. She was trained as a molecular scientist, had a PhD and had done years of laboratory work, which certainly helped her to successfully complete her bead-counting taper. Others may not be so lucky and will fail such a do-it-yourself taper even when they try as best as they can.

Earlier in this blog I wrote that pharmaceutical companies have been allowed to sell cars without having to verify if they have brakes that are functioning. It should not be necessary to instruct patients to make these brakes at home themselves. When they can use tapering strips they don’t have to. Tapering strips enable physicians to flexibly prescribe and implement personalized tapers without needing to work out a tapering schedule and explain to a patient how to implement it. For me, this is comparable to how we can use our mobile phones. All we have to do is click. No need to know or do all the things our phone knows and does to connect us with others.

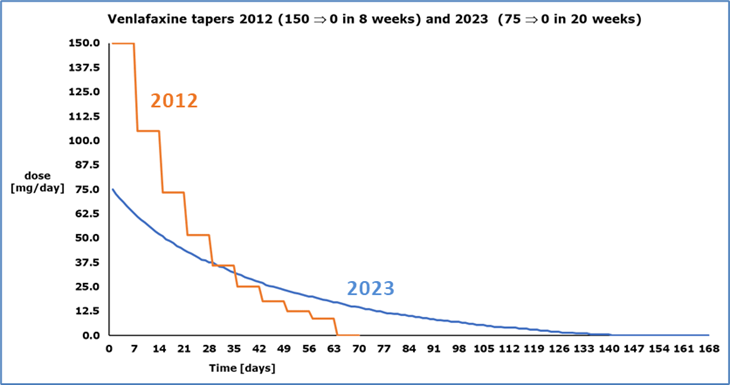

Experiencing the practicality of using tapering strips

As a patient I have experienced how easy it is to use the tapering strips myself. In 2023, for the second time, I decided to try to come off the venlafaxine I had been using for almost 20 years. A previous attempt in 2012, to taper from 150 mg/day to zero in 8 weeks, had failed. My educated guess was that 20 weeks to taper from the 75 mg/day which I had been using since 2012 could work for me. My GP agreed, filled in the prescription and within a week I could start my taper. The figure below shows that the 20-week hyperbolic tapering schedule I used is much more gradual than the ‘gradual’ 8-week stepwise tapering schedule I used in 2012.

The big difference between my 8-week and my 20-week taper

My 2012 ‘gradual’ taper was part of an N=1 experiment published in 2016. The taper itself was not difficult for me. I experienced complaints at certain moments, but they were much less than after forgetting a daily dose. Overall, I judged my 2012 taper to have gone very well. Problems started a few weeks after I had tapered completely. I became more irritable, slept less well, and thoughts of suicide returned regularly. This was not getting better and I feared it would get worse. After about four months, I decided to restart venlafaxine, hoping it would help me—which it did. Within a matter of weeks, at a dose of 75 mg, I started to feel much better. I decided not to go back to the 150 mg/day I had been using for 8 years, but to stay on 75 mg/day, which I did for another 10 years.

Despite the fact that my taper had failed I was satisfied with this outcome, because I was able to function again. It was of less concern to me that I could not determine if I had suffered from relapse, withdrawal or some form of dysregulation. With the knowledge I have today, I consider iatrogenic dysregulation the most likely explanation.

No signs of withdrawal during my 20-week taper

My 2023 taper was completely uneventful. There were no signs of withdrawal, which made it difficult for me not to forget to fill in the self-monitoring form we urge patients to fill in daily to be able to timely adapt a tapering schedule when withdrawal occurs. For my GP, filling in a prescription was enough to do a very good job.

After my 8-week taper I got problems, after my 20-week taper I remained fine

Because my 8-week taper in 2012 had gone well, I expected that my 20-week taper would go even better, which it did. What I was anxious to find out was what would happen after I had completed my taper. In 2012 this did not go well, which forced me to start using venlafaxine again for 10 more years. What would happen this time, after a taper that was much more gradual?

I was very happy to find out that this time I remained fine—I ended my taper 10 months ago—and more than that. I have lost some weight and the sexual side effects I have experienced from the moment I started to use venlafaxine 20 years ago, which have always been manageable for me, have gotten less. Other than that, I observe little difference.

My more gradual taper enabled me to stop using venlafaxine after 20 years

I speculate that I would have been able to come off venlafaxine 10 or 15 or more years ago if I had then been able to taper gradually enough, and that I would have had to remain on venlafaxine for the rest of my life if I had not had the opportunity to do this.

How well do tapering strips work? What evidence is available?

How representative my experiences with the tapering strips are for others remains to be seen. Patients can differ strongly in how much withdrawal they experience. This may depend on a personal susceptibility, but probably more on circumstances. Patients who experience severe withdrawal often have complicated medication histories. For instance, a history of using one antidepressant after another, in quick succession and with rapidly changing dosages, perhaps using one or more other withdrawal-causing prescription drugs as well, also changing in dose and combinations. Polypharmacy in patients who experience withdrawal is not rare. Guidelines generally do a very poor job in capturing this.

Thus far, it was difficult or impossible to study personalised gradual and hyperbolic tapering

Until recently, personalised gradual and hyperbolic tapering over longer periods of time was not studied because it was difficult or practically impossible to prescribe and implement the required tapering schedules. As a result, we had no data. The introduction of tapering strips marked the first opportunity to systematically study this approach, which we have done in four observational studies, published in 2018, 2020, 2021 and 2023, with a combined number of more than 2800 participants.

Differences with respect to randomized studies

To better appreciate the results of these observational studies, it is important to mention key differences with respect to randomized studies. Participants in our studies are likely a self-selected group of ‘difficult’ patients. Many were long-time users. More than 60% had experienced severe withdrawal during one or multiple tapering attempts in the past. This allowed for a comparison ‘within the person’ for a large number of participants, which is more informative for clinical practice than ‘between group’ comparisons in randomized trials. Many participants had to inform their doctor about the tapering strips, instead of the other way around—especially in the beginning, not as much today. In contrast to randomised studies, there were no exclusions for not having a specific DSM classification, for having suicidal thoughts or for any other reason. Every patient who had been prescribed one or more tapering strips could participate. There was no additional guidance. These differences contribute to greater external validity than can be achieved in randomized studies.

Given the absence of other substantial evidence, the results of our studies should be taken seriously. In summary, the results are that 70% of all participants were able to taper completely and that after 1-5 years 68% of the participants who had tapered completely were still off the medication they had tapered—thus far this was mostly antidepressants. In our last prospective study, ‘withdrawal in hyperbolic tapering trajectories of daily tiny steps was limited and rate dependent, taking the form of an approximate mirror-image of the rate of dose reduction’. In layman’s terms: more gradual tapering leads to less withdrawal.

My conclusion

An as yet unknown, but probably significant, number of people will be able to come off psychiatric prescription drugs like antidepressants, even after years of use and previous failed stop attempts with severe withdrawal, when they are given the opportunity to taper gradually enough to prevent withdrawal.

****

Disclosures: Peter has been involved in the development and research of the use of tapering medication, but not in the production, distribution, or provision of tapering strips, stabilizing strips, or switch strips to patients, for which he receives no compensation. The User Research Centre of UMC Utrecht has received an educational grant from the Regenboog Apotheek.

Thanks a lot for this blog Peter Groot. I have taken Paroxetine for more than 20 years. I have tried to stop twice, both times with severe withdrawals. The last time was 2019. I searched the internet for an expert about stopping with Paroxetine. I could not find anyone. Glad to know you do research and actually develop tapering strips. I hope to find the courage in the next few years to try to stop again, telling my doctor that tapering strips do exist!

Report comment

While the world waits to have access to your brilliant and humanitarian discovery, please know that the majority of these same medications are available in compounding pharmacies in liquid form and tiny changes in doses can be achieved with doctors orders. Withdrawal is a serious problem in the mental health world and too many end up back on the drugs just to avoid it.

Report comment

Dear Joy, withdrawal is indeed a very serious problem we must absolutely do something about. I understand why people resort to using liquid medications, when there are no better options available. But I strongly feel, as I explained in my blog, that better and safer options should be available for them. See this comment I wrote together with Jim van Os in the Pharmaceutical Journal: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/letters/exploring-the-safe-and-effective-tapering-solutions-in-the-nhs

Report comment

thank you Peter for sharing your story. the book is a great resource as is Mark’s site. Are the strips just compounded doses or is there a different manufacturing process?

Report comment

K; There is a diffferent manufacturing process, which means the pharmacist uses the API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) instead of crushed pills and from every batch a sample is send to the laboratory of the Dutch Pharmacist Association (KNMP)

Compounded doses are not always/very rare tested on the amount of medication, which is a crucial factor especially at the end of tapering, together with the importance to avoid varying amounts which can trigger withdrawal symptoms.

Report comment

thank you . I had noticed apparent rapid uptake of compounded olanzapine in a family member who is CYP 1A2 hyper inducer.

Report comment

Yes, Peter, the idea of needing to deal with the complication of understanding how to get the proper dose while using liquids is beyond many people. I am greatly encouraged by the system you have developed. I am very sure your approach will make getting off some of these medications a reality for the first time for many people. Thank you!

Report comment

Thank you for working to help bring to fruition, safe ways to wean off the psychiatric neurotoxins, Peter.

Report comment

We need tapering strips for many opioid meds. I just bought the DEPRESCRIPING

manual…thanks so much! And are these tapering strips available in the U.S.?

Report comment

Ann Maria; every doctor can prescribe them (www.taperingstrip.com).Regarding opioids; they are not allowed to be send to other countries. I know there are compounded low doses in the U.S., but don’t know the company ‘s name.

Report comment

When tapering off venlafaxine I emptied all the capsules into a jar and used a microgram jewelry scale to weigh dosages. Withdrawal from 75mg per day took me over two years. I initially weighed 75mg of sprinkles and reduced the weight by a small percentage every three weeks. It beats counting.

Report comment

The patience required to do that is amazing glad it worked

Report comment

Thank you! Thank you! My son has advocated for himself for over two years about his poly-medications being the cause rather than the cure for his symptoms. He had received very little support from the medical community. Now he has hope. Is it a possibility that tapering strips can become a method of treatment for those who are “addicted “ to non psychotropic drugs as well?

Report comment

Who knows, we can certainly try. Time will tell.

Report comment

Best wishes and positive thoughts to both of you from a family on the same journey

Report comment

Hello Peter

Re: tapping in the uk ( or there lack of)

Firstly, thank you for your efforts and work in this area.

I am a chartered Psychologist supporting a friend coming off anti psychotic medication and we are experiencing a number of obstacles in relation to communicating with her psychiatrist.

A few questions have emerged and even though presenting your papers, research and findings we have been unable to change his dogmatic stance.

Would it be at all possible with the understanding and appreciation your time is precious to as for a zoom call with you at your convenience to discuss further.

In anticipation and with gratitude.

Kind regards, Janice

Dr Janice Brydon

Chartered psychologist

Report comment

Hi Peter, I am on 30mg of Paroxetine 21 years now. I want to come off it, I’ve tried twice before but got very sick from the withdrawals, is it possible to take tapering strips made up like 29mg 28mg 27mg ect, down to 1mg? I want to do this as slowly as possible.

I’m based in Ireland

Report comment

Dear Tom,

when you visit https://www.taperingstrip.com/prescribing-and-ordering/, you can download a form that your doctor can use to indicate the medication you wish to taper, the starting dose, the target end dose, and the duration of the tapering process.

Once the signed prescription is received, the pharmacy will calculate a hyperbolic tapering trajectory for you, and you will receive the corresponding medication. This is essentially what you’re asking for — a gradual, personalized reduction in dosage.

I hope this helps you move forward.

Best regards, Peter

Report comment

Thank you for the reply.

Report comment