With all the recent coverage of the youth mental health crisis and the role of social media, little attention has been given to the way platforms like TikTok promote certain narratives about mental health—shifting not only the conversation but also the way mental health issues are actually experienced.

Young adults on college campuses and elsewhere are being persuaded to interpret their everyday lives through the lens of mental illness as algorithms target them repeatedly with ads and other content. The result is a form of “marketing” that encourages self-diagnosis and the embrace of disorders as identity by watering down the definition of mental suffering—and, paradoxically, minimizing understanding and compassion for those who are truly struggling.

Just ask the students themselves. In conversations with 19 college students and recent graduates around the country and the world, they expressed concern about their generation’s norms for discussing mental health and the way these norms disrupt their ability to cope.

“If somebody had a tough day, I think they’re more likely now to say, ‘My mental health has been rough,’ or use that sort of terminology, than they would have five years ago,” says Veronica, a recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College. For Veronica and other college students, psychiatric terms pop up everywhere: conversations with friends, emails from their universities, and even discussions about characters in literature classes.

“I guess it’s just more ambient now,” Veronica suggests.

Social media reinforces this, allowing younger generations to create an online culture that bursts with accounts run by mental health professionals and memes framing mental illness in funny and relatable ways. On TikTok, a platform where over 60 percent of users are under 30, posts tagged with #mentalhealth have over 100 billion views.

For some, social media is a source of community to rely on when real-life support or connection is hard to find. “Especially for kids who may not have friends around them, it allows them to just have someone tell you you’re not crazy, and you’re valid for being this way,” says Al Bowen, a recent graduate of the University of Colorado Denver.

Misha, a senior at Sarah Lawrence, used to post about his mental health issues on a secret Instagram account back in high school. While situations like nearly having a panic attack while ordering at a coffee shop felt embarrassing to talk about in real life, the account helped to normalize them. “To not be ashamed of something, you have to say it,” Misha explains.

And yet, simultaneously, engagement on social media platforms can be a source of profound distress. Despite having this resource that former generations lacked, rates of mental and emotional struggles still continue to rise among younger generations, with rates of major depressive episodes increasing by 63% for American young adults between 2009 and 2017—and social media likely plays a role in this.

“I feel like a seventy-five-year-old being like, ‘These kids on the internet!’” says Misha. “But no, it’s the kids on the internet.”

“A culture of oversharing”

For one, social media has altered the norms for talking about mental health both online and in person. One recent college graduate who, like others interviewed for this story, prefers to remain anonymous, notices a lack of necessary boundaries. “If you’re talking with your friend about something, you have that baseline level of trust and familiarity with each other,” she says. “But when I have my coworker telling me about all these heavy issues, it’s like, I don’t know you that well. I don’t know if we should be sharing these kinds of things with each other.”

On college campuses, this leads to competitive attitudes surrounding mental health issues. Adriana Adame, a junior at the University of Texas at Austin, hears many of her peers brag about their lack of food and sleep, which she attributes to an academic culture where neglecting your health is seen as a “badge” of success. “People don’t need to suffer to learn,” Adame says. “You can overcome challenges without putting your health in danger, you know?” Still, she finds it difficult to escape this way of thinking when fitting in on campus requires being perceived as hard-working and intelligent by your peers.

Caroline Renas is a junior at Sarah Lawrence—a historically women’s college with a majority-female student body—and links on-campus discussions of mental health to “coquette culture,” an online subculture that frames mental health issues as “womanly things” that are normal or even desirable for girls. Like Adame, Renas recognizes a sense of competition surrounding mental illness. “If you tell somebody that you have depression,” she says, “they’re like, ‘How long have you had that diagnosis? Because I’ve been diagnosed since I was eight.’”

This oversharing may have been worsened by the pandemic, when rising rates of mental health issues and decreased access to mental health services left many reliant on social media to cope. “Not to blame everything on COVID,” says Renas, “but we’ve lost a lot of social awareness for what’s okay to talk about in public… I think that, hopefully, as we move out of pandemic times, people’s social awareness will come back.”

Still, this extreme openness isn’t completely new—especially online. Many current college students spent their middle school years on Tumblr, where glamorization of mental illness was rampant. Misha, remembering graphic images of self-harm he came across on Tumblr at age 11, compares this to seeing a sign in a foreign language and trying to interpret it with limited context. “I had no ability to interact with it critically,” he says. “I could not read the language, if you will.”

This inability to “read the language” can lead young teens to recognize what a behavior is while lacking awareness of its meaning. One sophomore remembers seeing posts about unhealthy behaviors that she viewed as “quick coping skills” because she was oblivious to the “nuance and complexity” underlying them. “There were many behaviors mentioned that I simply would not have thought about beforehand that I wound up engaging in,” she says. “I feel like other people could have a similar experience where they see it and get almost inspired to do so without realizing what it means.”

“Pro-ana” communities, which frame eating disorders like anorexia as positive lifestyles and offer tips for losing weight, also proliferated on Tumblr. Now, this type of content is often subtler, detaching itself from official diagnostic labels while carrying the same messages. One example of this is a trend where users post what they eat in a day and display “almost no food.”

“It’s portrayed as something aspirational because it’s this pretty girl doing it,” explains one recent college graduate. “And if you go into the comments, it’s a lot of young girls being like, ‘I wish I looked like you!’”

Leo, another recent graduate, frequently sees these posts on alleged “recovery” accounts. “It’s a lot of body checking and reinforcing diet culture and not super recovery-promoting,” he says. “It’s like pseudo-recovery, basically.” He used to follow these accounts when he was in a “negative headspace,” leading to a vicious cycle when they only reinforced his symptoms.

For many students, memories of their early social media use cause concern for the generation below them. “I know technically you have to be 13 to join TikTok, but as we know, you can be 8 and be on TikTok,” says Renas. “And I think it’s causing a lot of issues for 8-year-olds being exposed to things that they probably shouldn’t be exposed to.”

Concept creep

Access to content about mental health can be valuable for those who are struggling and don’t know why, providing explanations for events that feel upsetting or out-of-control. “It feels really comforting to know that people are going through similar experiences as you and it’s not just a you problem,” says Renas.

But at the same time, mental health content often involves flat-out marketing—prompting people to redefine themselves as mentally ill.

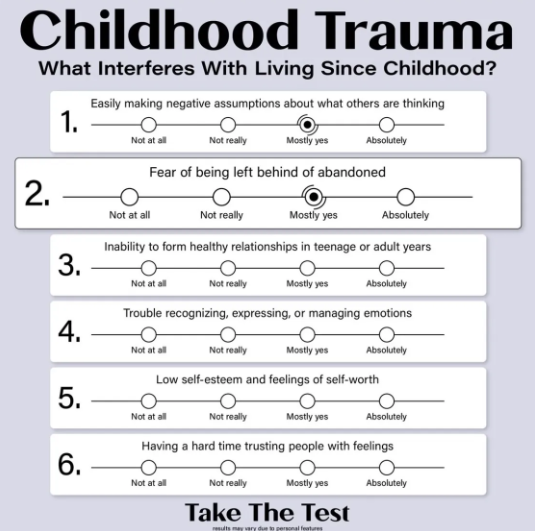

Take this ad, which relies on the fact that most people can’t resist a Buzzfeed-style personality quiz—even one that ends with self-diagnosis. By framing childhood trauma as entertainment, the ad distracts users from their usual associations with the concept and focuses on incredibly common experiences like having low self-esteem or struggling to manage emotions. In this way, childhood trauma is no longer a reaction to distressing events—instead, it’s a personality type, something anyone can discover in themselves, no matter their history.

Other ads ignore symptoms completely, leaning into playful caricatures of a diagnosis. As a result, depictions of psychiatric disorders end up being sanitized, and mental health issues—both online and in three dimensions—become a “funny punch line,” as Adame puts it.

Leo, who often hears students making suicide jokes on campus, says, “People making jokes about it is not increasing awareness in any way… You don’t need to equate failing a test or your future worries with, like, I’m gonna go kill myself. Those are like real experiences that real people have and warrant a little bit more seriousness.” He finds that social media has normalized these jokes to the point where people forget the gravity of what they’re saying. “At one point, I even found myself saying it,” Leo says, “and I was like, no, no, you can’t. Like, this goes against almost every value I have.”

Leo, who often hears students making suicide jokes on campus, says, “People making jokes about it is not increasing awareness in any way… You don’t need to equate failing a test or your future worries with, like, I’m gonna go kill myself. Those are like real experiences that real people have and warrant a little bit more seriousness.” He finds that social media has normalized these jokes to the point where people forget the gravity of what they’re saying. “At one point, I even found myself saying it,” Leo says, “and I was like, no, no, you can’t. Like, this goes against almost every value I have.”

Renas, who believes humor can sometimes be a good coping mechanism, also finds that social media “almost normalizes it too much.” When her peers casually throw around terms like “schizo” and “delusional” or use diagnoses as adjectives (“I’m so OCD”), it sends the message that normal or healthy behaviors are signs of a disorder.

This is an example of concept creep, where the meanings of harm-related concepts expand to refer to broader ranges of events. While concept creep can be a sign of empathy that recognizes overlooked forms of suffering, it also carries the risk of over-pathologizing people. For example, while mental health once meant an absence of mental illness, it’s increasingly conflated with well-being. Because of this, negative but normal experiences are framed as a lack of mental health—which, because of the term’s original definition, automatically implies a need for treatment.

Concept creep can also involve trivialized portraits of specific disorders. As Leo says, “I wouldn’t be surprised if the increase in mental health-focused social media in recent years has sparked these conversations where suddenly all of my friends think they have ADHD because they saw Reels”—short, algorithm-driven videos on Instagram or Facebook—“being like, ‘Can’t pay attention in class? You have ADHD.’”

“It’s a modern day equivalent of what you did as a child,” adds Bowen. “You think you’re sick and you look online and go, ‘Google, am I dying?’ And it goes, ‘Yes, you are. If you have a scratch, you’re dying’—and you think you’re dying.”

The looping effect

Platforms like TikTok use algorithms to curate users’ feeds and repeatedly expose them to the same types of content. Because of this, many people view their social media feeds as reflections of their identities—and when posts center on a specific diagnosis, it can feel like the platform is diagnosing them. Even when a disorder’s symptoms don’t align with someone’s real-life experiences, they may be tempted to incorporate the diagnosis into their self-concept due to the online communities and sense of identity attached to them.

“I think we all want to belong to something,” says Sarah Armstrong, a junior at Brigham Young University. “I think when we see people with ADHD do this, and they’re all thriving and happy and together in an online community, you’re like, that seems like something that I would want to be a part of.”

While this may seem harmless, believing you have a mental health condition can do more than just change your beliefs. For one, seeing increasingly mild distress as symptomatic reduces distress tolerance, so people actually feel distress in a wider range of situations, and low distress tolerance is associated with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses.

Plus, attaching yourself to a diagnostic label can lead to a looping effect, where people, often unconsciously, conform to the categories they see themselves as falling under. In this way, self-diagnosis based on a watered-down list of behaviors can lead someone to eventually develop the disorder’s more serious symptoms.

The looping effect can be profitable for companies in the mental health sphere, who can market not only products themselves but also the very idea of having a psychiatric disorder. Mental health advertising is all over social media—Armstrong gets ads for symptom management apps “probably every day,” while Leo sees ads for actual medications. “When I think of going and getting mental health treatment, I think of going to an office, a little more of a formal process,” he explains. “And then suddenly I’m watching a show on Hulu, and I see an ad in which I can go get anxiety meds online.”

Many students also see ads for clinical trials, like this one. While there’s nothing wrong with seeking participants with a certain disorder, this ad speaks primarily to those without a social anxiety diagnosis, implying that anyone who dislikes large gatherings should seek treatment.

Repeated exposure to these ads can encourage people to apply diagnostic terms to themselves. Veronica, who frequently sees ads for clinical trials on depression, asks, “How does the algorithm decide that I’m depressed? What do I do that makes them think that?” before adding, “Maybe it’s something in my behavior recently that reeks of depression.”

“I think advertisements might be targeting people that are struggling and trying to make it worse, trying to force them to go to their services,” says Bowen—and because of the looping effect, this may be truer than many of us realize.

“Stigmatized in a different way”

Many students do appreciate discussions about mental health on social media for how they reduce stigma and promote openness about mental health topics. “I never worry about having to tell somebody I’m in therapy and them immediately assuming something’s wrong with me,” says Renas, while Fran Kenney, a recent Sarah Lawrence graduate, notes that mental health terminology is “woven into our everyday lives,” making it easier to explain symptoms to the people around her.

Still, stigma around mental health issues isn’t completely gone—and in some ways, it may actually be getting worse. As Misha puts it, “Mental illness is not actually being normalized. It’s just being stigmatized in a different way.”

What Misha means is that, instead of being stigmatized for having a mental illness, people are stigmatized for displaying symptoms that don’t match the social media stereotypes of a disorder. “I feel like I’m constantly comparing myself to how other people describe their own mental illness,” says Halle Martin, a student at Azusa Pacific University. “I feel like I can’t say I’m depressed if I’m not experiencing depression in the same way someone else is.”

In particular, social media’s focus on aspects of emotional or mental distress that students call “cutesy” and “romanticized” tends to obscure the harsher realities underneath. “People will be like, ‘Ah, yes, I know what depression is,’” says Misha. “’I understand the realities of it. I am an ally to the mental health community.‘ And then they walk into your house and they’re like, ‘This is disgusting. There’s something deeply wrong with you.’”

Online tropes can also make it harder to communicate with others about the real difficulties that come along with mental health issues. “I feel like mental illness is literally everywhere,” says Martin. “This makes me feel like the significance of my depression is lost because everyone thinks they have it.”

For some, disclosing a diagnosis still leads to the opposite reaction. “People have less faith in me than they usually do,” says one college sophomore about her experiences disclosing her borderline personality disorder (BPD) diagnosis.

Andy Dente-Ferguson, a junior at Sarah Lawrence, suggests that a dichotomy exists between conditions like anxiety and depression, which are destigmatized to the point of being embraced too widely, and more “taboo” disorders like BPD and schizophrenia, which never stopped being stigmatized. “Where can you go to find the actual support that you need, and also not be coddled fully?” Dente-Ferguson asks.

Other students find themselves facing a similar conundrum, and many with more severe mental health issues have trouble accessing adequate support—especially on campus, where resources are overloaded and often center on milder issues like academic stress. “There’s an unspoken understanding that you cannot enter those spaces with the more unpleasant side of your illness,” says Lila, a psychology student at the University of Kent in the United Kingdom, “because it’s abrasive, disturbing, or just not how someone should behave in public.”

Even when support is available, social media stereotypes can still make it hard to seek help. When Bowen was younger, for example, they attributed their panic attacks and emotional dysregulation to ADHD based on online information—but this label did little to help.

“I was like, I’m just quirky. I just can’t focus sometimes,” Bowen explains. “And so I didn’t get help for like twenty years.”

Better in person

When asked how accepted mental health issues are on his college’s campus, Leo echoes something many others express: “People are accepting, which is great. But I don’t know how far their understanding goes.”

Social media plays a major role in this lack of understanding, normalizing mental health issues without accurately showing what these issues actually are. A 2022 report found that nearly a third of TikToks tagged with #mentalhealthadvice or #mentalhealthtips contained misinformation, while studies on specific disorders have found even higher rates.

Some students, aware of social media’s limited credibility, curate their feeds around research-based accounts or those that align with their own experiences, while others confine mental health discussions to tight-knit groups of friends. “The conversations I have with my friends and my family and people in my life always feel more productive,” says Finn O’Sullivan, a recent graduate from the University of Colorado Denver. “It’s more of a conversation instead of just information being shown to you… It feels more like a community.”

Still, it’s hard to be fully immune to social media and its veneer of intimacy. “You go on Tumblr, you see people being sad, and you’re like, this is life, this is true,” says Misha. “It’s false authenticity that’s still being treated as real authenticity.”

Similarly, Renas has seen a number of YouTubers who are sponsored by BetterHelp—an online counseling service that has gotten in trouble for deceiving customers in the past—claiming to speak about their personal experiences when advertising the service. However, she notices that they tend to follow a similar script. “I don’t know if it’s actually their personal experience or if it’s just what BetterHelp is telling them to say,” Renas says.

Social media also poses the risk of spreading misinformation much more quickly. “In person, if you say the wrong thing in a conversation, someone will be like, ‘That’s not right.’ And then you have to face it,” says Bowen. “You know, the world’s not going to suffer from someone saying something wrong—unless you’re on the Internet, and you have a ton of followers, and there are a bunch of teenagers looking up to you.”

It’s possible that college campuses could help to reshape the conversation around mental health. Noting the difficulty of striking a balance between oversharing and minimizing mental health issues, Leo says, “I wish we had more real conversations where people didn’t feel the pressure to perform and play the Oppression Olympics… I think that’s both the responsibility of students and also the college itself to facilitate spaces for those interactions to happen.”

****

MIA Reports are supported by reader subscriptions and by a grant from Open Excellence. Please subscribe to help fund our original journalism.

Interesting article Zoe:

From a quick scan, 4 questions: I. On the internet or in the internet?

II. Swallowed in the use and being used by the Tech, to be at the edge?

III. Across the ages?

IV. Accepting of mental health labels – If the discussion has been framed by the industry to process “the mentally ill” as a function made in part possible by the aggregation of the ONEness of a soul, into the many, then how can an individual share with others how and then why they managed to Re-cover?

Thanks for sharing your insights!

Report comment

What a great article! I so agree with this analysis of how social media/tech is shaping these discussions. During my college experience (10+years ago now) I knew of some students that were kicked off campus/removed for self-harm, being suicidally depressed, or attempting to end their lives. The college punished them because they were a legal liability. If the student was allowed back on campus they had to have a “treatment team” and agree to go to therapy+take drugs+ talk to a dean of students once a semester.

There were around 8 suicides in my four years at my undergraduate institution. I don’t see how these social media conversations are doing any good for young people. I think the de-stigmatize language is a trap. Disorders like BPD, Schizophrenia, discussions about widespread real child abuse (not just having parents that yell sometimes), poverty, climate crisis anxiety — these topics still seem taboo. I’ve done my own bit of oversharing as an older millennial online and don’t use much social media anymore as a result. My point is that many of these young people will come to regret it. We all know “mental illness” is not just like diabetes. Just look at how “disorders” like schizophrenia and personality disorders are treated…

Report comment

Don’t let tiktok and instagram and social media mesmerise you to the broader structural dysfunctions of which they are just exaggerated examples. ALL thinking, including ALL of your thinking, is group think. Social media is where we find the proliferation of populist opinions and intellectual posturing and forms of ‘virtue’ signalling, including signalling the ‘virtue’ of hating the appropriate group or party. This we might call more vulgar forms of group think in which tribal ethnic elements in our consciousness want to assert superiority which gives a primordial bliss of self-delight. Obviously these archaic residues need to be put away for a more compassionate and intelligent consciousness to operate.

And all political and intellectual lives are conducted within social discourses, are wholly conditioned by them, are wholly governed by the rules and codes of conduct within those discursive fields, so ALL your thinking, writing and speaking is group think UNLESS AND ONLY WHEN it is words to convey something beyond words, as an artist would paint a scene. Then it is not group think at all. So the future basis of consciousness will be poetic philosophic exposition of what is using words, not logic or maths which we can leave to the computers and AI. And it is only your artificial intelligence that feels threatened by AI. Real intelligence sees that being a computer or computer brained person makes you stupid because blind and presumptuous and deluded, rather then intelligent. If a computer believed it’s computer codes were reality, we’d say they were mad. But we believe our words and thoughts are reality, and created stupid computers in our image.

Report comment

I believe there is a stigma to mental health issues = there is a stigma to mental health issues.

Or does it?

Report comment

The TikTokification of Mental Health on Campus is an innovative approach to addressing student well-being. By leveraging a platform students already engage with, this initiative makes mental health support more accessible and relatable. It’s a fantastic way to break the stigma and foster a supportive community!

Report comment

to break the stigma

One first has to accept the advice from those directing it that that there is a stigma.

We do not all.

Report comment

Sadly not breaking anything and certainly not stigma. Just the beginning of time costing when the exploration of LIFE affirming questions spoken need to heard or sens3d.

Report comment

Your comment reminds me of an article I once read on The Guardian titled, “The word ‘stigma’ should not be used in mental health campaigns” by Mike Smith. It’s a really good article, and I think back to this sentence here: “by using words like stigma to describe society’s collective perceptions of mental health problems and the personal and social challenges people face, we accept the stigma and buy into the very concepts we are trying to challenge.”

I acknowledge that people mean well when using the word “stigma,” but with how mental health is being “stigmatized in a different way,” it exposes the flaws of “destigmatization” to begin with. Should the focus really be on “starting conversations” about mental health and suicide or should it be on dismantling the oppression that survivors of mental illnesses and suicide attempts have faced for centuries? The focus should really be on the latter, and with that, the focus should be on “anti-sanism” rather than “destigmatization.” After all, facing human rights violations as a survivor—that’s not stigma. That’s sanism.

Report comment

This article really resonates with me, because as a college student, I’ve also noticed that mental health discussions have focused on “starting conversations.” Never mind that not everyone has the privilege of being vulnerable. Especially as it pertains to survivors of severe mental illnesses, they risk facing ostracism at work or in social circles if they are honest about their state of mind. State violence in the form of police brutality, involuntary commitment, neglect/abuse in psychiatric facilities, and drained finances are also real possibilities. Yet mental health and suicide prevention organizations don’t prioritize bluntly calling out those things. In their own way, they prolong sanism by ignoring those issues and failing to center survivors of severe mental illnesses and suicide attempts in their movements (both of whom are and should be recognized as marginalized groups).

Speaking of which, I’d go as far as to say that the words “stigma” and “destigmatization” are euphemisms for the real issue at play: sanism and oppression. I’ve noticed that the words “stigma” and “destigmatization” haven’t led to improved social standing for survivors of severe mental illnesses. They continue to be sidelined in the mainstream movement and their oppression ignored. Even with social media, there’s a lot of respectability politics surrounding mental health discussions and how people talk about mental health when it’s comfortable for them. Yet when it comes to having harder discussions about it, they want to check out. People need to have their boundaries, but at the same time, I’ve felt the strains of sanism and the performative care from others when I bring up the subject. Sanism continues to plague society in so many ways, from the language to institutions. But how many are ready for those dialogues or to really learn more about that? For the record, I’m a survivor of severe depression, multiple suicide attempts, and multiple hospitalizations myself.

The double-edged sword of social media on mental health dialogues is definitely something I’ll write about in the future, with this article being used as a reference. What colleges (and society in general) need to do differently is to call out systemic sanism and dismantle it in all the structures. Dialogues can be used as catalysts for that, but they need not be the only method. Also, centering those most impacted by sanism (i.e., survivors of severe mental illnesses, suicide attempts, institutionalization) should be prioritized. But I get that since society still sees those groups as “incapacitated” and without autonomy, that will be considered “too radical” of a move. But there is a need to make the mental health and suicide prevention movements radical, and I hope I live to see the radicalism go mainstream.

Report comment

The healthy people claim they have “mental illness” and as a result get awarded different benefits such as the victim status and more social recognition and support. Yet when people with genuine neurological illness like schizophrenia mention their condition or it becomes apparent, they get ostracised and discriminated against. The concept of “mental health” does a lot of harm as it lumps together neurological illness, psychological disorders, and situational problems. Any anti-stigma campaign should be scientific and should clearly differentiate between these 3 categories. By failing to differentiate between such heterogeneous groups “mental health literacy” reinforces the misleading and highly stigmatising concept of “mental illness”. Until people understand this, the oppressed and marginalised will continue to be oppressed and marginalised by the privileged. And the privileged will continue to mislabel their own emotions as “mental illness” and then claim that they are oppressed. Then they divert human rights efforts away from the real victims and onto themselves. As they further marginalise those with genuine illness and push them out of the “mental illness” space.

Report comment