Editor’s Note: This story, written by Carro Magnusson, first appeared on Mad in Sweden.

I don’t know what day it is.

I don’t know what time it is. Or what the weather is like outside. Hardly even what season. In my memory it is always autumn. According to my journals it was March. It doesn’t matter, because I’m cold anyway. The sterile rubber mattress—unworthy of its length to save the laundry in Alingså’s various eiderdown bolsters impregnated with bodily fluids—seems to cool down rather than insulate the little body heat I manage to generate, and the blue-and-white striped county council blanket that I have tightly wrapped around me helps very little. But that’s all I have. If nothing else, it’s the only comfort there is here, in ward 362 at Östra Sjukhuset in Gothenburg. One of the bipolar wards, which I don’t actually belong to but have been sent to due to the usual lack of space.

I’ve come here from the surgical emergency department, where I spent a week to date before having my third mental breakdown that spring. It was called choledochus stones with icterus and it must hurt. That was my least problem with that stay. The staff—at least most of them—were kind and difficult to deal with. After all these years in psychiatry, it’s programmed into my DNA that healthcare professionals don’t want me well and I’ve been avoiding healthcare as much as possible for several years now. Unless absolutely necessary. Pretty sure I broke my foot once, but couldn’t bring myself to seek medical attention. It passed, that too. If there’s one thing that never comes up, it’s surgery because I can’t bring myself to give total power to a doctor. Sadly, that’s exactly what they advised me to do. “Must” was the word they used.

A couple of days before, I had been given permission to euthanize my cat urgently. Another week or so before, another doctor had prescribed a 12-year course of sertraline in two weeks. It would then take about three years before the last withdrawal symptoms stopped. About a week before that, things had ended between me and my girlfriend at the time. Even before that, I had had covid and sustained long-term breathing difficulties that the health center refused to investigate. When I had covid, I read in my medical records that I had been discharged from the outpatient psychiatric clinic in Gamlestaden. “Unjustified” was the explanation. By then I had struggled for three years to get help with the post-traumatic stress that was consuming me in parts. The one, which was partly a result of inpatient psychiatry. Later also outpatient psychiatry, which refused to listen.

The damage to my liver had turned me yellow, as I lay shivering in the hard bed. It must have cut something horribly against the blue bedclothes. You old, you free. I stared straight ahead, out the window that faced another part of the hospital. Daring nothing but keeping my eyes fixed on an anonymous spot on the dirty concrete wall, because I felt like I would be annihilated if I thought about anything at all. Closing my eyes was out of the question. I was in active starvation, had lost 11 kilos in a month, but I had no idea yet. At the emergency department I had tested positive for ketone release, but no one reacted. It felt like I was constantly falling, straight into a pitch black abyss and the only thing that could hold me up was the bland concrete spot right in front of me.

“I understand manias and psychoses, but I don’t understand sadness,” the head doctor on the ward had said. At first she gave a kind impression and it had felt good. As a small extension of the mostly friendly treatment I had received at the surgeon. She came into my room one morning. I was still asleep—still cradled in the soft cloud the sleeping pills created—and didn’t understand what was happening. She told the mental health worker she had in tow to go out and get me a cup of coffee, because didn’t he see I was tired? “Can we talk?” she asked me and before I knew it I had been placed in a chair and had a cup of coffee in my hand. I told her what had happened. She said I was welcome to stay, and then those words. That she doesn’t understand sadness. I had to go back to my bed. And to my sadness that no one understood.

My attempt at average concrete wall-induced self-hypnosis is slightly interrupted when I hear a young person—the one in the next room—outside the door. She is standing and talking on the phone. Perhaps a bit too loud for it to be customary for a care unit, although that is just speculation. I’m not an expert. I don’t know if there is a custom of modesty in hospitals. After a couple of minutes, I hear a mental health worker approach and a discussion about something—perhaps about her high-frequency phone habits—breaks out.

“Take it easy!” it comes from the mental nurse. He also doesn’t seem to have any further idea of whether there is a low-key custom in hospitals or not, because he had raised his voice several decibels. His colleagues come running and now they are all standing there gaping. “Take it easy! Take it easy! Take it easy!” they chant in chorus around the young woman. She becomes noticeably stressed and raised her voice even more, she too. I had become that too. Stressed, that is. Not loud. I wouldn’t have dared otherwise. Someone presses their alarm button and the alarm blares throughout the department.

The alarm. I don’t know how many people have heard that alarm before, if you can even imagine what it’s like before doing it. An ominous hybrid between a fire siren and the “Hesa Fredrik” siren feels like an apt enough description, but it doesn’t give the whole picture. The alarm is designed so that it should sound loud enough to be heard from all departments in the entire psychiatric unit. Now why they don’t just have blaring pagers or some other cozier alternative is beyond me, but there’s so much I don’t know. The alarm cuts through the bones and it is impossible to get rid of the sound, no matter how hard you try. Afterwards, it rings in the ears for a good while and if you, like me, were acutely exhausted and thus hypersensitive to the smallest, smallest sound, it is close to torture we are dealing with.

I hear people come running outside my door and I squint, although I dare not. Desperately pressing the pillow to my ears to try to shut out the sound but it doesn’t help no matter how hard I press. I could have just as easily not. The young person—how old could she have been? Nineteen, twenty years at the most—screaming. A scream in pure, animalistic death terror; she pleads with them to let her go as she is wrestled to the floor with a crash.

“You can’t treat people like this! You can’t treat people like this! You can’t treat people like this!” echoes her voice through the corridor as she is dragged away to the belt bed, the humiliation and the exposure. Both she and the alarm went silent after a couple of minutes and I have tears in my eyes, absorbing some of her fear and making it mine. Because I couldn’t help. Because all I could do was lie here with my grief that no one understands, totally powerless in the face of the fact that another human was being abused with only a thin wall between us and I couldn’t stop it.

“Up with you!”

It is morning. I don’t remember falling asleep. Someone is standing in my room screaming.

“Up with you! You shall not lie and be lazy all day!” continues the harsh voice and I feel someone kicking the bed. An arm grabs mine and pulls me out of bed.

The kind head doctor, who did not understand grief but who understood manias and psychoses, holds my upper arm in a firm grip.

“You shouldn’t lie in bed all day!”

I stare at her in what I have to equate to shock.

“What do you think I should do then?” I asked dejectedly.

“You can draw!”

I certainly could. All departments have a craft room. I had been there a few days before to survey the terrain, as I actually enjoy drawing. They are designed in the same way; two large cupboards stand against the inner wall and a long table with chairs around stands proud in the middle of the room. Only the material differs between the departments. It depends somewhat on how the head of the care unit budgets. Often there are beads, hobby paints, drawing pencils, pastel crayons, paper in a few well-chosen colors, brushes and watercolors. In ward 362 there was a small jar of colored pencils. Most were orange, a few were blue. I think I managed to find a green one too. Complementing these was a smaller stack of white copy paper. There was no pencil sharpener either, so most pencils were unusable as they were too worn. Where there is usually a TV in the wards, there was an empty wall. The sofas—which have since been replaced by chairs in all departments except one when it was said that the patients would not be too comfortable—were not there either. There weren’t even chairs, except in the dining room. What was there was a large whiteboard, which in garish red felt-tip pen announced the rules of the department. All patients must be awake by 07:30. Dinner is served at 3 p.m. You may not stay in the common areas except for meals, which you may not take in the room.

I am unable to answer. It’s certainly not needed either, because the kind senior doctor who didn’t understand grief has gotten a kick out of what I have on my bedside table. A hundred-gram bag of Good and Mixed, two-thirds of the contents left and a half-drunken bottle of Coca-Cola. That’s all I got in three days.

“YOU SHOULD GET UP!” she screams. “You shouldn’t lie here all day chowing down on candy and coke!”

She marches with determined steps out of the room. I look at the clock. It wasn’t even 8:00 in the morning. I feel something in me, a primal force of some kind come to life. Whoever it is tells me that under no circumstances should I accept this anymore. With my last strength, I get out of bed and into my shoes and go after the kind chief doctor. She who did not understand sadness. Because I want to explain that this is not, absolutely not how you treat people in grief or even to someone and even I understand that, lack of university credits and ST service notwithstanding. She had already disappeared behind the heavy, locked sluice door between the ward and the rest of the world when I come out into the lounge. Then I step firmly to the reception and demand to be signed out instead. There is some risk involved in doing so. It may happen that you are given the choice between remaining in the department “voluntarily” or that a care certificate is written. I once asked a senior doctor if it was really legal to do that. “Do you want it legal? Then we will do it legally!” I got in reply. I objected that there was absolutely no need.

As I stand there waiting for the staff, I overhear a conversation between a mental health worker and another patient. Out of respect for her, I do not intend to reproduce it as it was. But I can tell she cried. She cried inconsolably and told how she didn’t want to live anymore. That her life felt unbearable and how she had planned to try to escape from her suffering before the police came and took her there. I glance in her direction, and I see that the man from the staff she is talking to—probably at the urging of the kind head doctor who didn’t understand grief when I had been told the same thing in our first conversation—is making himself unavailable. He stares straight ahead, doesn’t move a minute. Gives no indication whatsoever that he even notices that she is there. She cries and says she doesn’t want to live. He ignores her.

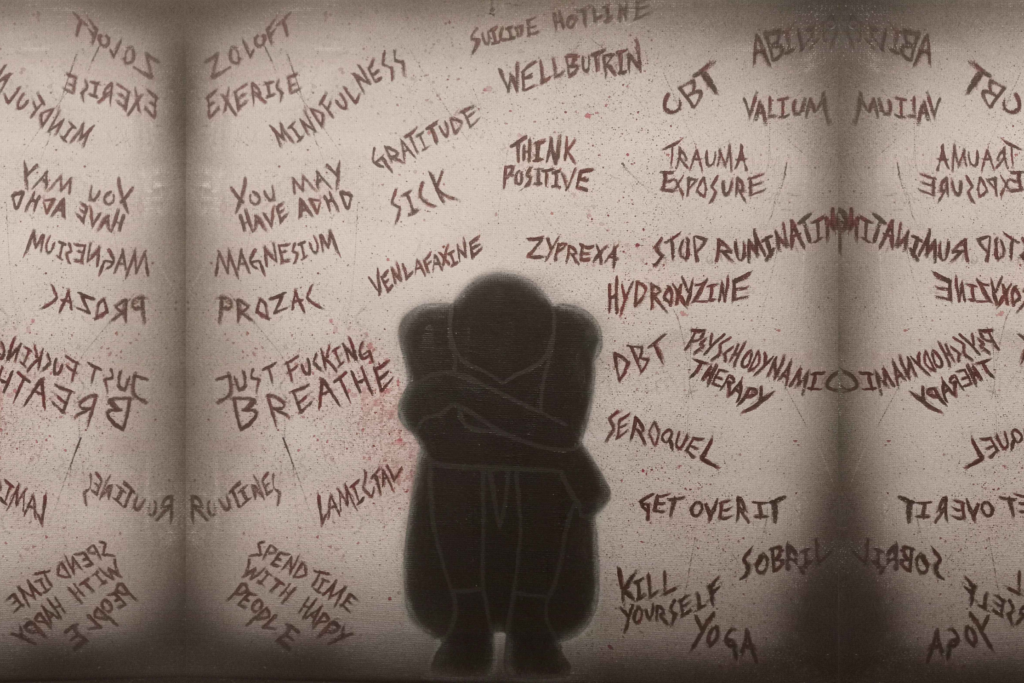

It’s like something is missing. It’s so inhumane. The only real support offered to these people—people who, like me, find themselves in deep grief stuck under a different diagnosis code—is to monologue in front of someone who so obviously goes out of his way not to listen. Although it should be so obvious that it is exactly what a person in grief needs. It is a human reflex to turn to other people when our suffering becomes too overwhelming. Even people with incurable cancer rate lower on pain scales when they get to hold a loved one’s hand for a while, and probably the kind head doctor who didn’t understand grief should at least once in her life have been so eternally sad herself and turned to a fellow human being for to receive comfort and support, and then to feel a little better? Yet there is no understanding that people with psychiatric diagnoses have that need, because our feelings never seem to be allowed to be feelings but are reduced to medical symptoms. The fact that that need is tangible enough for someone to find themselves standing and holding a monologue in front of someone who turns themselves into a wall is telling.

The kind head doctor said she didn’t understand grief, but manias and psychoses. The question is, isn’t it exactly the same thing, anyway? The only difference between me and them—between the bipolar diagnosis and my professionally recognized grief—was that I could present a clear sequence of events that led me to where I was, and that was because it wasn’t that far back in time. For example, a broken childhood that perhaps no one has ever managed to identify as the triggering factor for the manias and psychoses, despite the fact that science speaks its language. There is an underlying cause for every human suffering and it is not spelled chemical imbalance in the brain. The cure is not medication, belt beds, coercion and wall monologues but in someone who takes you by the hand and says “You know what? I understand your sadness.” Maybe in being allowed to lie in bed as long as you want and being allowed to eat sweets when nothing else works.

When I finally get a discharge interview (the kind head doctor resolutely refused to see me and sent me an unknown colleague) and walk out through the heavy sluice door that separates psychiatric patients from the outside world, I think that she was absolutely right, the scared young person in the room next to mine.

You can’t treat people like this.

“How to Heal Intergenerational Trauma with Teal Swan” | EP 60 Healing & Human Potential with Alyssa Nobriga

Report comment

Dear Carro,

Your story is so beautifully written. Love the juxtaposition of the “kind, head doctor” with her actions. I’m so sorry that more pain was heaped on top of the pain you already held.

No, “they shouldn’t treat people like this”, but they do and call themselves wise and good “professionals” for doing so.

Hope that one day your grief softens to the point it is only a hum- a whisper of what it has been.

Report comment

Fortunately, I have never been in a psychiatric facility. But your story resembles some sort of fiction of a hell that seems inconceivable in the 21st Century. And yet it is not fiction. We humans are alienated from one another– and as Carl Jung put it, “Man feels himself isolated in the cosmos. He is no longer involved in nature and has lost his emotional participation in natural events, which hitherto had a symbolic meaning for him.” And of course we can see, that it is not only the poor patient who is denied numinosity, but most of us in the Western world: “Nothing is holy any longer.” (Jung again.) Awhile back, I read about a man who was so depressed he could not bring himself to get out of bed. This went on for quite a length of time. Someone who knew him (I imagine he was a friend) decided on a plan. The “friend” went to his house and simply sat beside his bed–no words–for an hour or so every day and continued to do so until one day the depressed person got up, went on with his life and never returned to the previous state. That was all it took–someone who cared. No drugs or hospitalization was necessary. I am so sad that we have lot our ability to care for one another, whatever that may take!

Thank you, Carro Magnusson, for reminding the world what is still happening. Perhaps some of us will make attempts to relieve the suffering!

Report comment

the horror,the horror. The entire evil is captured in this sharing from Carro. Lies,indifference and cruelty. How do people come back from this experience of trauma? What always amazes me is the worldwide replication of the same disgusting sadistic behaviour from health CARE professionals. Birdsong I’m off to look at Teal swan. K

Report comment

K, Carro’s story is so horrific I couldn’t read it in its entirety.

You ask, “How do people come back from this experience of trauma?” to which I respond many do not, including myself. The so-called “mental health industry” parades itself as a beacon of healing knowledge when all it is is a waking nightmare that for many IS impossible to escape despite their best efforts and/or the misguided urgings of impossibly ignorant people unaware of something best described as their own compassionate cruelty.

But DO check out Teal Swan’s videos; she’s a recent discovery of mine. She just released a video about how people are programmed to believe that expressing negative emotions of any kind are “sins” of some sort, or in today’s “mental health” parlance, an “illness”, instead of what they TRULY are: feelings that carry important messages or, simply signs of our humanity.

Be sure not to miss Teal’s interview @inspiredevolution as it’s truly incredible along with her interview with Alyssa Nobriga EP 60 entitled “How to Heal Intergenerational Trauma”. Both are well worth the time.

Report comment

thank you so much for the recommendations much appreciated.

k

Report comment

My pleasure! ☺️

Report comment

Clarification: Be sure not to miss Amrit Sandhu’s interview with Teal Swan @InspiredEvolution

Report comment

K, your definition of “psychiatry” is SPOT ON: lies, indifference and cruelty.

Report comment

Carro, my hope is that you will always feel free to express your grief in any way that feels authentic to you at any given moment in time for as long as you need to, be in written or spoken form. In other words, I hope you don’t let the rest of your life be dominated by professionals who think it’s their job to tell you how they think you should express – or not express – your own deeply personal grief.

Report comment

…and the same goes for well-meaning people who haven’t learned how to mind their own business.

Report comment

“Something happened and we don’t have words for it.”

MELANCHOLY and the exquisite intensity of life ~ This Jungian Life

Report comment