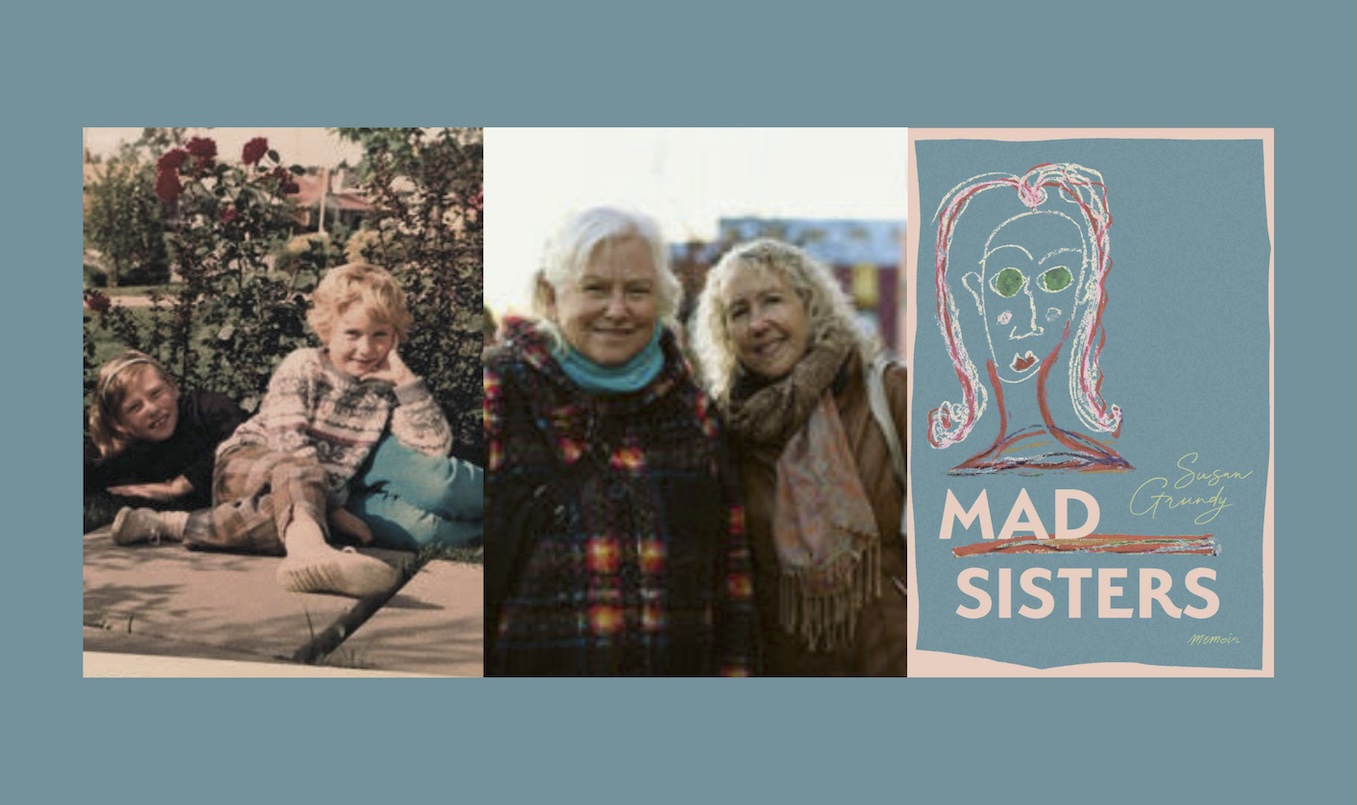

Susan Grundy is an author who writes about the weight of emotional distress and an easier way of being. Her book, Mad Sisters, is a highly personal account of her caregiving journey for an older sister diagnosed with schizophrenia at the age of 13. When not at her writing desk, Susan can be found walking in nature towards a café. She divides her time between Montreal and London.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Brooke Siem: I was lucky enough to get an advanced copy of Mad Sisters. It struck me as odd that throughout the book, you refer to your parents as “Norman” and “Lorna” rather than “father” and “mother.” Can you explain your relationship with your parents?

Susan Grundy: We lived in a very adult-centric household. It wasn’t touchy-feely or “mummy-daddy.” I think that reflects the disconnect between the parents and the children. Another term that comes up a lot is “darling.” My parents called each other “darling,” and my editor picked up on that. My sister, Nancy, and I also call each other “darling,” but there’s a little edge to it between us, like, “Darling, I told you already.” With my parents, it was definitely a term of affection. Thank you for pointing that out. I think it reflects the distance between my parents and my sister and me.

Siem: Can you tell us what happened when you were a child? Your sister Nancy was 13. How old were you?

Grundy: I was 10. We had moved a year earlier from a quiet suburb in Toronto to urban Montreal, a much more upscale area. That meant no sprawling backyards or places to play. It felt much more conservative, and the move was difficult. It was hard to integrate into the new community.

My sister had always been the perfect child before the move and even during our first year in Montreal. She was very obedient to our parents, who were strict with many rules. She followed them, unlike me—I was the rebel, always getting into trouble and seeking fun outside the household. She stayed home and worked hard to please our parents.

When we moved, the school curriculum in Ontario was behind Quebec. Nancy would have been held back a grade, especially since she was a bit older than me, but instead, she worked tirelessly. She stayed glued to her desk that first year and earned top marks in her class, which was impressive but not surprising, given her personality.

Then, suddenly, she had a dramatic psychotic episode. It happened overnight, during a long summer weekend. It was very hot, and we had all gone to bed early. I was woken in the middle of the night by strange noises from our bedroom. At 10 years old, I didn’t understand what I was witnessing. All I can say is, years later, when I saw the film The Exorcist, I couldn’t handle it because it reminded me of her breakdown.

She was hallucinating and screaming, and we didn’t know what was happening. She was taken to the hospital, and a few days later, they diagnosed her with schizophrenia. She was transferred to the Allen Memorial Hospital in Montreal, a psychiatric hospital housed in an imposing white mansion on Mount Royal. Because schizophrenia is rare at 13, there wasn’t an adolescent ward. She was placed with adults, and I think she had a very hard time. She was 13, very feminine, pretty, and blossoming sexually. She told me she was surrounded by adult men. I can’t imagine how uncomfortable she felt in that environment.

When she came home, I didn’t recognize her. She was so heavily medicated. She felt like a zombie—a sister who wasn’t my sister anymore, almost an imposter.

Siem: What year was this?

Grundy: ’68.

Siem: 1968. Definitely a different era in terms of how this would be handled now. For better or worse—that’s highly debatable.

Grundy: Not different enough, but we can talk about that.

Siem: Looking back now, what do you think happened that night when Nancy was 13?

Grundy: I have to contain my emotions when I think about this. Schizophrenia—what does that even mean? That night, I think she just exploded. Hormones, obviously. She was 13. People ask if there was an incident or if something happened. I think she was just fed up. She had been under so much pressure. The move wasn’t easy, and we had no support from our parents. I can’t imagine what she went through. She just broke.

Her way of coping with the family and our situation had stopped working. She couldn’t go on like that anymore. Yes, she was hallucinating. I remember she thought she was Rudolf Nureyev. I remember she thought she was Hitler and wanted to throw herself off the balcony. It was real. It wasn’t made up. But I believe it was this incredible breaking point. It was a place she could go to under pressure. But with proper support and care, she wouldn’t necessarily have to go there. She needed help, and she wasn’t getting it. Like you said, the pivotal moment wasn’t just the break—it was what happened in the hospital.

And here’s an interesting anecdote: the Allen Memorial Hospital had just been in the news at that time for conducting LSD experiments on psychiatric patients for a CIA-funded program.

Siem: I remember reading about the history of LSD and how that came about. I didn’t realize Allen Memorial was involved.

Grundy: There were a few hospitals, but in Canada, that was the one. There was a lawsuit and a settlement—$100,000 per family, under the table. Nancy missed that fate, but she was pumped full of drugs. It was a life sentence for her.

She’s been on those medications ever since. She just turned 70. Her doses may be lower now because her metabolism has slowed, but that day she came home—I didn’t recognize her. She could barely talk; her mouth was frozen, and her tongue felt like lead. She couldn’t pronounce consonants. She looked dead to me.

Eventually, she adapted somewhat, so she wasn’t as much of a zombie, but she had behavioral issues. That was the beginning of her “prison term,” and she’s still living it. I don’t want to say it’s too late for my sister—I have hope—but she’s 70. I certainly wouldn’t want anyone else to go through what she’s endured.

Siem: How much time passed between that night and when she was taken to the hospital?

Grundy: None at all. She was rushed there—hours, really.

Siem: In retrospect, knowing what you know now, do you think there would have been a benefit in waiting and giving it time?

Grundy: I think a little critical thinking about what was happening and the psychology behind her behavior would have been helpful. I’ve been reading a book called Why Psychosis Is Not So Crazy by a professor from Ghent University. It argues for looking into what’s behind the behavior rather than just treating the behavior.

I’m sure there was some level of analysis with my sister, but from what I’ve witnessed as her main point person for decades, her treatment has always been drug-focused. Her appointments are about adjusting medications—nothing about the psychology behind her behavior or what’s really going on.

Siem: Often, the extent to which someone can go low correlates to how high they can go, like with mania in bipolar disorder. With Nancy, you talk about her artistic ability and her brilliant paintings. I can’t help but think the darkness of her psychosis must have influenced her creative side as well. I’d love to hear what’s beautiful about Nancy, what you love about her, and why you’ve dedicated so many years to helping and caring for her.

Grundy: That’s an interesting question because, for the first 10 years of my life, we weren’t friends at all. She was the perfect child, and I was the wild one, so there was a disconnect between us—just like with our parents.

The irony is that we’re closer now than ever. Would we have been friends if she hadn’t been in this situation, where I became her caregiver? I’m not sure.

But the beautiful things about Nancy are her humor and her wit. Readers of the book will see how I wove in her anecdotes—she fires them off one after another. She’s extremely bright. People smile when I mention her name. When we go to a café, everyone knows her and adores her.

Of course, there’s another side. When we fight, it’s not pretty—there can be nasty moments. But her humor, her logic, and her resilience are incredible.

She’s 70 years old and has withstood so much. She was in a locked ward for 14 years but came out and kept bouncing back. It’s harder now because, as you age, you start thinking, “This is my life. There are no more chances. I’m not going to meet someone, fall in love, have children, or be a painter.” She’s fighting her bitterness about that, but her resilience amazes me.

I’m so proud of her strength. I use the metaphor of swimming a lot in the book because it starts with her saving me from drowning. At the beginning of the book, she’s the capable one, swimming in the deep end. I get washed into the deep end and start drowning, and she saves me. By the end of the book, I have this epiphany that may be obvious to others but isn’t always obvious to caregivers: she’s a strong swimmer. I realized I needed to be careful not to overstep when “saving” her because she’s capable of saving herself. It’s about respecting that boundary.

Siem: How is it that you became the primary caregiver instead of your parents?

Grundy: I’ve forgiven Norman and Lorna, and honestly, I wasn’t even mad at them at the time.

When my sister was 25, she’d spent her adolescence revolving in and out of hospitals but had managed to get a fine arts degree, which was amazing. But at 28—sorry, I was 25, and she was 28—she went into the hospital again. This time, she must have stayed too long for their protocol because they declared her chronic.

Normally, she’d be in the hospital for two or three months, but this stay went over three months. She was at the Montreal General Hospital, and we had a family meeting. I remember it very clearly. The doctor, wearing a business suit, was at the head of the table. It was very somber. He said something along the lines of, “It’s best if your sister is transferred to the Douglas Hospital,” which is a psychiatric institution. I don’t remember his exact words, but the implication was long-term care.

There was silence. My parents—my heart goes out to them—didn’t question the doctor. Back then, the doctor was God. I think my mother was taking notes, as she always did in these meetings, but her pen just dropped, and she stared at him.

Siem: Was she exhibiting symptoms at the time that made you all think this meeting was different from the others?

Grundy: There’s one answer to that: she wasn’t responding to the medication.

Siem: What did that mean exactly?

Grundy: It meant that they couldn’t calm her. She’s always been one of those “untreatable” patients. She had gone to the hospital because she was very agitated. I think she was just looking for freedom. She’d been dancing on the roof of her apartment building. She’s never been suicidal, but she was taken away in an ambulance. I think about that often. Rooftopping can be about exploring and seeking freedom—I love rooftops myself. My son loves rooftop exploring. But in her case, it led to her being hospitalized. Sometimes, being in a hospital can actually make you sicker.

I can’t say with 100% certainty why the doctors made the decision, but the explanation we got was that she wasn’t responding to medication. They said Douglas had a great research team and could take better care of her. So, they shipped her off, and she ended up staying there for 13 or 14 years in a locked ward.

During her first year there, my father received a job transfer offer in Germany. He was 60. I suggested he take early retirement, but he accepted the transfer. I think they wanted out.

Nancy had been sick since she was 13 and was 28 by then. She hadn’t lived at home in recent years, and when she had, it was tumultuous. My parents fought with her a lot. They didn’t fully accept her illness and would yell and scream when she misbehaved. I think they wanted to start a new life, so they left.

I stepped up. I was 25, and in a way, it gave me a chance to prove myself—to be responsible and helpful, to gain their approval.

Siem: I got a sense from the book of you stepping into the role of the “good daughter.”

Grundy: My sister and I gradually switched roles. Once she became ill, my marks improved while hers plummeted. I became the responsible one. It was a definite role reversal.

Siem: Looking back over Nancy’s care—referring not to your care but to the medical system’s—can you identify points where you questioned the decisions made or wished things had been done differently?

Grundy: When I started being the caregiver at 25, she was in a locked ward, and I wasn’t very involved in her medication. But as the years went on—oh, yes, I have a list. It’s hard to know where to start.

Siem: Why don’t we start with that correspondence you had with one of her psychiatrists?

Grundy: That involves a medication called Clozaril. The generic name is clozapine. It’s considered a last-resort drug—a second-generation antipsychotic prescribed when nothing else works.

Nancy had been in the locked ward from age 28 through her 30s and into her early 40s. When she was 42, there were provincial healthcare cutbacks. Douglas had to reduce its number of beds. It’s interesting that, around the same time, they started her on Clozaril. Shortly after, she was discharged—almost overnight. The medication reduced her agitation, cleared her thoughts, and suddenly, she was deemed ready to leave.

She stayed on Clozaril for 20 years, until COVID hit in 2020. By then, she was living alone between hospital stays because she couldn’t manage group homes—they have rules, and Nancy doesn’t follow rules. She had been kicked out of a group home after many years, so I put her up in an apartment. It was that or a geriatric ward.

During the pandemic, she thrived. She told me, “I’m used to lockdown.” I was nervous about COVID, and she said, “Paranoia will destroy you.” She was doing well. Her Clozaril dosage was reduced, and she felt free for the first time.

But when she came off Clozaril, she struggled to sleep. The medication is sedating, and without it, she slept only a few hours a night. Normally, she sleeps 10 hours. After a week of this, she started showing signs of mania. I’d never seen mania like that before.

Siem: It’s my understanding that sleeplessness can often trigger schizophrenic episodes or mania.

Grundy: That’s what I think happened. I think the lack of sleep triggered the mania. And I’m not a pharmacologist, but I believe the dopamine that had been suppressed for so long surged when she came off Clozaril. Combined with the lack of sleep, it turned into mania.

I started writing to her doctor who has what feels like 800,000 patients. He admitted the medications are often trial and error. By August 2020, Nancy was still on a reduced dose of Clozaril. I wrote, “Please note that Nancy would like to further reduce Clozaril. She’s doing well with the reduced dosage so far.”

However, that summer, she had two skin infections. One side effect of Clozaril is that it lowers your white blood cell count, specifically neutrophils, which are critical for fighting infections. That’s why patients on Clozaril require weekly blood work to monitor neutrophil levels.

Siem: Wow.

Grundy: By late August, she wanted to further reduce the dose. Then in October, things changed. On October 19th, I wrote, “Nancy slept only a few hours last night. She feels she needs to resume Clozaril every night, at least for the next few weeks. Her pills are being delivered today, but she’s panicking that she won’t have them in time.”

[Interviewer note: Nancy was also prescribed clonazepam (Klonopin) at this time.]

A week later, on October 27th, I followed up: “After a week of taking clonazepam, which Nancy calls ‘little blue pills,’ she only slept well the first night. She takes one pill at bedtime and a second at midnight but is still only sleeping about four hours a night. Not enough. She’s coping, but now she’s slowing down physically and can’t complete her usual walks. Should we try something else?”

By November 14th, I wrote again: “Nancy has been very agitated the last few days. She describes her head as being very full. She called me at 4:30 a.m., upset that she couldn’t sleep despite taking three clonazepam. I’m wondering if this agitation is due to the Trileptal she started on Tuesday, on top of the lithium. Should she stop the Trileptal? Maybe this change is too soon after stopping Clozaril.”

A week later, on November 20th: “Nancy tried the new regime for two nights. She’s still not sleeping well. Last night, she took her bedtime pills at 9:00, including four clonazepam. She didn’t fall asleep until 5:00 a.m. and woke up at 6:00. I’m concerned.”

Another week later, I noted: “Since starting Tegretol to replace lithium, Nancy seems ‘up.’ Sometimes too high—laughing over the top. Yesterday, she walked from Park Avenue to Benny, a distance she hadn’t walked in a decade. She tells me, ‘This is the real Nancy.’ However, she’s also leaving screaming voicemails and yelling at her landlord. That behavior isn’t new, but her sleeping still isn’t sufficient. Do you have a plan to start reducing the lithium?”

By early January 2021, the situation had worsened. I wrote: “Nancy was admitted to the Douglas a few days ago after spending several nights in the ICU. She called 911 herself on December 30th and was taken to the general hospital before being transferred to the Douglas. The nurse tells me Nancy is still very high despite new medications. I’m wondering if this mania is a delayed reaction to stopping Clozaril. It’s hard to make sense of it all.”

I sent so many emails. Reading back over them now is frustrating because it feels like a slow decline.

Siem: Were you getting responses?

Grundy: Yes, but they were from one overburdened psychiatrist. Nancy really needed a team. There was a psychiatric nurse, but she wasn’t very responsive or available. The feeling I got was, “She’s like a shooting star—let her burn out, and we’ll start again.” There was no real sense of urgency or care.

Siem: It’s heartbreaking that Nancy lived most of her life medicated to the point where she never really had the chance to know who she truly was. That’s such a tragedy in psychiatry. What are your thoughts on that, as someone who knew her before all of this?

Grundy: You’re right—it’s one of the biggest tragedies. I knew Nancy before this happened. She was bright, funny, and artistic, with so much potential. The medications have shaped so much of her life, and it’s impossible to separate what’s her illness, what’s her true self, and what’s the effect of years of medication.

Nancy never had the chance to fully live without the constraints of either her illness or the treatments. It’s devastating to see how little room she had to just be.

What you said earlier, Brooke, about the extremes—how if Nancy can go that low, maybe she can go that high—that really resonates with me. It ties into her artistic temperament, which has been stolen from her, and completely squashed.

Nancy is an abstract painter, and I see the energy in her art. I miss that energy. The day she came back from the hospital, she had just turned 14, and she was a zombie. I remember her sitting on her bed, chin on her chest, not moving. I called her for lunch, and it felt so wrong. She was the one who used to call me for lunch. But she was so overmedicated, and her body was still developing.

A couple of times, in her 20s, she went off her medication—or reduced it. I remember actually having a great time with her downtown. She’s told me those were some of the best days of her life, bopping around, feeling like herself.

Siem: In Nancy’s clearer moments, how does she feel about all of this—everything that’s happened to her?

Grundy: I think about that question all the time. She vacillates between anger and bitterness, mourning a life lost, and then becoming very practical. She says things like “doctors know best,” almost echoing our parents’ philosophy from another era. In fairness to my parents, they accepted her diagnosis and treatment without question because that’s what you did then. Now, we know to ask questions—doctors are human, and I think many of them welcome those questions. But Nancy doesn’t.

I talked to her yesterday about this podcast. We were discussing her dosette, her weekly pill organizer. She takes about 15, maybe 20 pills a day. I said, “Nancy, I want to talk about what this medication has done to you—leukemia, diabetes, the tumor on your pancreas. There’s debate about some of it, but the diabetes for sure, and the leaking kidneys.”

Her response? “It’s all Latin to me.” And she’s right—it’s another language. These names—loxapine, Tegretol, Trileptal—it’s overwhelming. She’s obedient in some ways, still, that young girl before she was ill, but she’s also torn.

Siem: Was it worth it?

Grundy: The medication?

Siem: Yes, was it worth the trade-off?

Grundy: No. My immediate gut answer is no—it wasn’t worth it. Fourteen years in a locked ward, the physical toll on her body, the suffering she’s endured—none of it was worth it. She’s so stoic, but she’s suffered so much. I’m not against drugs; they can have a purpose. But I am against treatment that relies predominantly on medication.

Like with any condition—whether it’s metabolic, psychiatric, or something else—you need a holistic approach. Diet, lifestyle, exercise, sleep—these are all critical elements. Medication can be important, but we rely too heavily on it.

We should be asking bigger questions: why is this happening? What’s the psychology behind the behavior? My sister doesn’t believe in talk therapy, but there are other kinds of therapy, alternative approaches, that might work for her. There’s a humanitarian approach to psychiatry gaining traction, and I hope it continues to grow.

For example, I discovered Mad in America after naming my book Mad Sisters. I attended a lecture by Bob Whitaker at the Douglas Hospital in Montreal. Nancy’s psychiatrist was in the audience. That lecture was transformative for me. I left the lecture so enthused. It shifted my perspective while writing the book. Originally, it was about caregiving, but it turned into a critique of the healthcare system and a call for systemic change. It’s clear from Nancy’s story that she’s a victim of her treatment.

A week after that lecture, Nancy and I were in her psychiatrist’s office. I’d been telling Nancy about this movement and how there are calls for a different approach to psychiatry. She brought it up in front of her psychiatrist—almost as a dig at me. She said, “My sister thinks all of this is nonsense,” or something like that.

I had to sit there and take it because she’s the patient. I couldn’t defend myself. Her psychiatrist just raised an eyebrow. I’ve never talked to him about it, but I think he knows I’m not advocating for her to go off medication entirely. I just believe in asking questions and considering alternatives. But that moment was funny, in its own way.

Siem: In some ways, it’s a beautiful full-circle moment that Bob Whitaker was lecturing at the same hospital that played such a significant role in Nancy’s story. It shows there has been some progress. To me, though, it’s still shocking how little it seems to change the way we actually work in the world. But there is change.

Grundy: As I said earlier, not enough. In Nancy’s last hospitalization this January, the same patterns emerged. She hit rock bottom, called 911 herself, and asked to go to the Jewish General Hospital because I had told her they had excellent psychiatric care. But they rejected her after a day because she’s a Douglas client. She ended up at the Douglas.

She spent 10 days in their emergency ward. In Canada, it’s not uncommon to hear complaints about waiting 24 or 36 hours in an emergency, but 10 days? She wasn’t seeing a doctor—just staff trying to maintain calm in a tense environment. Nancy, of course, deteriorated further and ended up in the ICU.

Siem: Was that due more to her physical symptoms?

Grundy: Good question. At the same time as all the psychological symptoms, she was suffering from low sodium.

Siem: I’ve heard of this before. There’s something about low sodium and some of these drugs.

Grundy: It’s related to Tegretol, no doubt. Nancy drinks a lot of water as a nervous habit—she overhydrates. I’d rather she do that than smoke, which she also does sometimes. But with Tegretol, her sodium levels dipped dangerously low.

At the Jewish General, the psychiatrist immediately flagged her low sodium levels, which was helpful. But after her transfer to the Douglas, she went another 10 days before anyone addressed it. By then, she was disoriented and deteriorating further. Finally, they transferred her to a general hospital for a sodium drip.

The problem is this disconnect—the two silos of physical and mental health care. The physical hospital didn’t understand why she was there; they just knew she needed a sodium drip. And the psychiatric hospital didn’t seem equipped to address her physical condition. The two systems weren’t communicating, and Nancy was caught in the middle.

Siem: She just needed an electrolyte packet.

Grundy: Exactly! It’s sodium—something so basic. But instead, there were delays, misunderstandings, and unnecessary suffering. On top of that, the root cause—her medication—wasn’t addressed. Tegretol was meant to replace lithium, which had caused her permanent Parkinsonian shaking. But Tegretol is incompatible with Clozaril, so she was taken off that at the time. The whole situation was chaotic, and Nancy bore the brunt of it.

Siem: What would you say to a parent or sibling of someone who experiences a psychotic break similar to Nancy’s, and is deciding what to do next?

Grundy: That’s a hard question, but I have an answer. The first step is to accept what’s happening. I’m not saying don’t seek help but embrace the reality. My parents didn’t do that—they rejected it as “not normal.” Acceptance is key.

Next, the family needs to be deeply involved in the medical care. Too often, families are treated as invisible partners. Advocacy is critical. You have to be vocal, stand up for your loved one, and ensure their needs are met.

Finally, pay close attention to the medication. Don’t rely solely on it, though. Stay curious—ask questions about why this is happening and what might have triggered it.

Siem: Did anyone ever ask Nancy, in the early days, what she wanted?

Grundy: I doubt it. When she first came home as a zombie, she couldn’t even talk. She likely had no say in anything. That might explain why she started acting out as she unfroze from the overmedication.

Her belligerent behavior was her way of trying to regain power. Even now, I think her need for control stems from a lifetime of feeling like she has none.

Siem: My last question: Your book is about caregiving, finding the line between care, love, and enabling. What advice would you give to other caregivers in similar situations?

Grundy: There’s such a huge need for this conversation. At my book launch, the response was overwhelming—it was standing-room only.

The word “enabling” is crucial. A social worker once accused me of being an enabler. At first, I didn’t understand; I thought, “I’m doing all the favors!” But caregiving can become all-consuming. I slid into it gradually, but soon I was completely entrenched.

You start thinking you’re saving someone, but the ego gets involved. I crossed boundaries into Nancy’s power space, which disempowered her. No wonder we had wicked bickering moments—she felt powerless, and I felt resentful of the responsibility.

The turning point for me was realizing that Nancy is very competent in certain areas. Letting her take care of things herself—even if she stumbles—was liberating for both of us. It’s like letting a child fall and skin their knee; it’s not the end of the world.

For caregivers, it’s not about taking a holiday or “relaxing.” It’s about recognizing boundaries and giving the person you’re caring for room to grow. Now, I assess every situation: When do I intervene, and when do I step back?

This approach has brought Nancy and me closer than ever. She’s asking for help when she needs it, and I’m respecting her independence.

Siem: That’s wonderful to hear. Where can people find you, and do you have any closing thoughts?

Grundy: You can find me everywhere—please support independent bookstores when you can.

My closing thought is that we need more care and compassion in this world. Humanity struggles with mental health as a continuum, and recovery is impossible without compassion.

Siem: Thank you so much, Susan, for being here and sharing the story of both you and Nancy.

Grundy: Thank you, Brooke.

***

MIA Reports are supported by a grant from Open Excellence, and by donations from MIA readers. To donate, visit: https://www.madinamerica.com/

Parents who see their offspring as objects to be fixed. Doctors who see patients as objects to be controlled.

WHERE’S THE HUMANITY IN THIS???

Report comment

Not always, but many times it’s one or both parents who are the problem or part of the problem but they don’t want to see that. Or it’s something else like bullying in school but so many parents are taught to seek professional help rather than try to talk to their children about what is wrong and deal with things as a family. Honestly, if I had a child who would become so hysterical like that (seemingly out of the blue) I would be so worried too like their parents were.

Psychiatrists are trained to see their patients as having a brain that is chemically unbalanced and they need to fix it with medications. Most of them can’t or don’t want to see beyond their training and see the whole person either because they don’t know how to do that because they weren’t trained and educated to do that or simply because it’s easier to just put their patients on medications and let psychotherapists do the therapy and figure out their mental and emotional struggles.

Here in the US, it’s pretty much separated like that now. It wasn’t always like that though. Psychiatrists used to do therapy too but when psychiatry became medicalized, biological psychiatry took over. Psychiatrists generally have a very narrow-minded view of mental health or mental illness so to speak. So much of this is about ignorance, denial and ego.

Western medicine deals with medicating symptoms and not in seeing the whole person. At least in real medicine doctors are able to take blood tests and x-rays to prove an actual medical illness (like diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure or gallstones and so many other things), which doesn’t exist in psychiatry. Psychiatric medications can be helpful at times. They helped me. I think the main problem is always using medications as the “answer” when so much of the time it isn’t. Also, over-medicating people is a huge problem. Too many medications at too high doses. It’s crazy.

It would have been nice to hear the other sister’s side of the story too in this article especially since she sees things differently. I like to see many sides to the “same” story to get different perspectives.

Report comment

Parents who automatically outsource looking after their children to “mental health experts” don’t deserve to call themselves parents, imho.

Report comment

This interview reminds me of a movie I saw years ago called “In Her Shoes”… as best as I recall, I think there was a scene in which a character recalls a husband saying about his wife (who took her own life after being forcibly hospitalized for “psychiatric problems”) “Nobody ever asked HER what SHE wanted…”

It made it worth watching.

Report comment

That sounds like an interesting movie. I’ll check into it.

Report comment

Hope you like it 🙂

Report comment

Thanks.

Report comment

Thank U for posting about this movie. i will definently check it out also. it very well could be a piece of the mental illness puzzle that will help me in the horrible battle to help my son.

Report comment