Seventeen years after the United Nations called for an end to coercive psychiatric practices, forced treatment remains widespread, legally sanctioned, and largely unreformed.

In a new article published in a special issue of the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry on “Mental Health Law,” legal scholar Laura Davidson reviews the limited progress made in this area. Despite the 2006 adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which demanded a shift from involuntary treatment and institutional care to autonomy, equality, and non-discrimination, Davidson finds that the core practices the treaty sought to eliminate remain firmly entrenched.

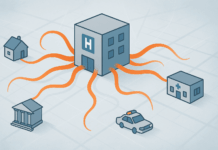

Focusing on the legal frameworks of England and Wales but drawing implications for global mental health governance, Davidson critiques the continued dominance of the biomedical model and the political deadlock among UN bodies over coercive care.

“Hard cases”— those involving violence, crisis, or perceived incapacity—are still routinely used to justify detentions and forced interventions, in direct contradiction to the CRPD’s call for rights-based alternatives.

“The wide-ranging scope of discriminatory, coercive practices prohibited under the CRPD encompass involuntary hospitalisation and enforced medical treatment, mechanical, physical, and chemical restraining, and forced seclusion and segregation,” she writes.

Does it make sense to describe individuals experiencing various states of emotional distress (alienation, prolonged bereavement, withdrawal, defiance, depression, fear of body shaming and bullying, etc.) as people afflicted with “disabilities?” Perhaps their alleged psychiatric disorders are not a genuine syndrome at all, but a justified response to rejection, ridicule, or unrealistic expectations on the part of their parents, peers, and society in general. The word “disability” often carries negative connotations, which I think are misplaced when it’s applied with an overly broad brush by mental health practitioners who fancy themselves the ultimate arbiters of appropriate conduct.

Report comment

I think they are talking the social model of disability, not the medical one, ie disabled by society. Its a moot point because it means not able to take part in society due to socuety not taking thought over one’s behaviors or states of mind. I’m disabled because I’m hard of hearing which means I cant take part in many meetings unless there us a hearing loop. I also can’t function near my family as they were repeatedly horrid over a long period of time and for a large part if my life found being around most people difficult. My hearing loss was partly caused by working with loud machinery, my social problems were largely from suffering a nasty alcoholic step mother and an arrogant tosser of a father. Both loud noise and nasty people left me moderatly disabled. With understanding and a few adjustments I can function in most environments if I have to and if people are understanding and thoughtful.

Report comment

The concept of “disability” in reference to non-physical phenomena such as thoughts or emotions has meaning only in a given social or cultural context. For example, in western societies a person who beholds ecstatic visions and hears an otherworldly voice directing him to walk about naked with a begging bowl and engage in various ascetic practices is likely to be labeled with a psychiatric diagnosis and forced to undergo psychiatric treatment, but in the Jain religion such behavior is not only accepted but revered as a manifestation of sublime spirituality and divine inspiration.

Report comment

Haven’t we all “lived through madness and distress” already? For goodness sake, Covid was societal madness, so was 9/11/01, and both were legitimately distressing. No doubt, it’s past time for the psych industries to take a long hard look in the mirror … and come towards understanding the hard truth … it’s past time for big change, scientifically “invalid” DSM “bible” billers.

Report comment