After years of misdiagnosis and psychiatric trial-and-error, I discovered that the real problem wasn’t depression — it was a broken brain circuit. Here’s how I found the map psychiatry forgot.

I was born in an emergency C-section after a uterine rupture — deprived of oxygen, but quickly declared “fine.”

At age five, I was diagnosed with auditory processing disorder. No one explained why. It was the first red flag — a subtle sign that something in my brain’s relay system had misfired early on.

Still, I lived a normal life.

I smoked weed through adolescence and into adulthood — and honestly, it worked. I had friends, relationships, creative energy, traveled the world, graduated college, held jobs. I was fully functional.

Then one day, after more than a decade of daily use, I quit weed.

That decision flipped my entire world upside down three months later. Within weeks, I was experiencing symptoms that made no psychological sense:

-

- A neutral, frozen emotional state

- 24/7 ice pick migraines

- A feeling of unreality so pervasive I couldn’t recognize myself in the mirror

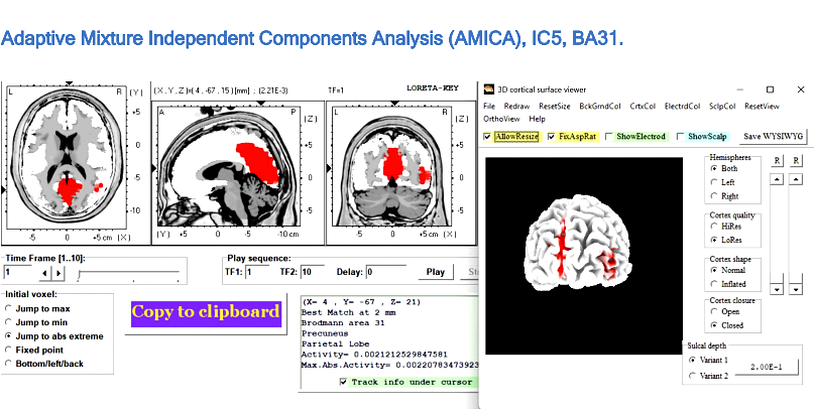

Weed wasn’t just a drug I used. Daily cannabis use may have been inadvertently stabilizing my fragile glutamate system, dampening excitotoxic activity. Especially with high-THC strains, cannabis can modulate NMDA receptor activity and reduce unstable glutamate firing. In my case, it seemed to act like a chemical crutch, dampening the overactive, unstable signaling between the thalamus and cortex. It didn’t fix the problem. But it kept the disconnection muted, so I could live a normal life — friends, school, travel, girlfriends.

Eventually, I quit — not realizing what I was holding together. And the fragile house of cards collapsed.

Enter Psychiatry

I figured maybe I was depressed. So I saw a psychiatrist. He labeled me with Major Depressive Disorder and began the ritual: pill after pill after pill. Nothing worked.

So I kept trying. I saw six more psychiatrists. I explained the same bizarre symptoms over and over, but they didn’t fit the manual — so I was stamped with “anxiety,” “atypical depression,” or just “treatment-resistant.”

Eventually, one psychiatrist, hearing that I’d failed every antidepressant, gave me something different: Lamotrigine (Lamictal)— an anticonvulsant.

Within weeks, the ice pick migraines stopped — completely.

It wasn’t just that my mood improved (it didn’t, at first). It was that something deep in my brain had finally calmed — like the misfiring had stopped, and the noise had gone quiet.

Psychiatry Had No Map — So I Found One Myself

Instantly, I was re-labeled: Bipolar II. Because in psychiatry, if an antidepressant fails but an anticonvulsant works, you must be bipolar. But I wasn’t. I wasn’t moody. I wasn’t manic. I was disconnected. And Lamotrigine wasn’t fixing my mood — it was repairing my circuits.

That’s when I stopped trusting psychiatry and started studying neuroscience.

When Lamotrigine stopped the migraines, I knew something was wrong — not with me, but with the model.

I wasn’t “less depressed.” I wasn’t “elevated” or “manic.” What happened was physiological: my brain calmed, my pain vanished, and for the first time in months, I could feel presence. But no psychiatrist could explain why. So I started looking deeper — not into psychology, but neuroanatomy.

The Brain Isn’t a Bag of Chemicals — It’s a Circuit Board

In psychiatry, everything is boiled down to serotonin, dopamine, and vague emotions. But the brain doesn’t operate on feelings alone — it runs on loops, rhythms, and relay systems.

That’s when I found something I had never once heard mentioned in a psychiatric office: the Brodmann system.

It’s a cortical map of the brain — 52 regions, each with a distinct function.

-

- BA7 helps you locate your body in space

- BA31 links self-awareness and time-memory integration

- BA24 (anterior cingulate) is your emotional compass and attention control

- The insula blends physical sensation with emotion

- The precuneus helps simulate yourself in social and spatial contexts

All of these regions are standard in neuroscience and neurology. Yet in psychiatry? Not even mentioned.

And at the center of all these cortical hubs sits the thalamus — the brain’s sensory relay. It doesn’t just route input , it binds consciousness itself. When the thalamus isn’t syncing with the cortex, the entire network goes dark. You don’t just feel sad — you feel like a ghost in your own body.

There’s a name for this condition, even if it’s not in the DSM yet: Thalamocortical disconnection.

My Symptoms Weren’t Psychological — They Were Topographic

For years, I kept trying to explain what I was feeling:

“The world looks foggy. Like it’s in 2D, not 3D.”

“I don’t feel like I’m in my body. I can’t feel time passing.”

“It’s not sadness. It’s like reality doesn’t land in my mind anymore.”

But each time, I was told it was anxiety. Or trauma. Or just more “treatment-resistant depression.” I was given more SSRIs. More SNRIs. None worked.

Eventually, I underwent a quantitative EEG (qEEG) — a scan that measures brain wave activity and shows which circuits are dysregulated.

What it showed floored me:

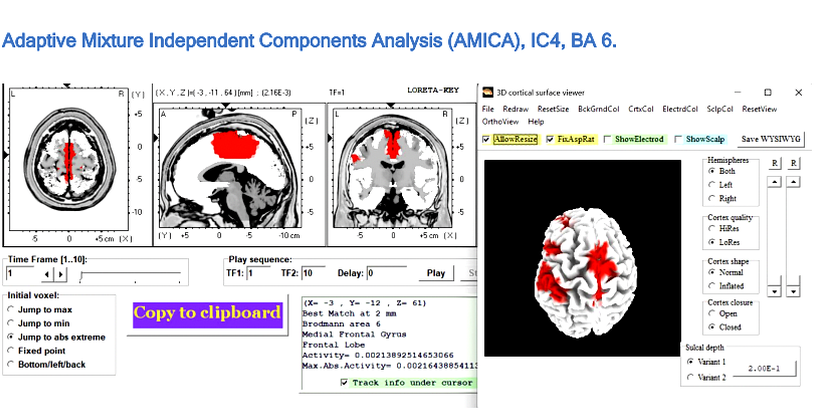

I had 14 dysregulated Brodmann areas. Every region matched my symptoms:

-

- BA41/42 — auditory processing (I was diagnosed with this at age five)

- BA31 — self-awareness and derealization

- BA7 — spatial disorientation

- BA24 — emotional blunting

- The insula — disconnection from bodily sensation

It was the first objective proof I’d ever seen — proof that my symptoms were coming from real, identifiable regions of the brain.

The Puzzle Snapped Into Place

Suddenly, everything I’d experienced made sense.

My problem wasn’t “depression.” It was signal failure — a literal disruption between the thalamus and cortex, especially in regions responsible for identity, emotion, and sensory integration. And Lamotrigine helped because it modulates voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels — calming hyperexcitable cortical neurons and restoring functional rhythm.

Later, I added Memantine, an NMDA antagonist that regulates glutamate, the neurotransmitter responsible for plasticity, learning, and attention. That’s when things really started to shift. I began experiencing “flickers” — brief flashes of clarity, memory, and realness.

This wasn’t mood regulation. This was circuit reintegration.

The first image shows BA6, a motor integration area. The second is BA31 — the heart of self-awareness and derealization.

Both circuits were severely dysregulated.

It was a functional disconnect — and psychiatry had no map for it.

Recovery Was Reconnection

When I first took Lamotrigine, the world didn’t instantly return. But something shifted. The ice pick migraines I had 24/7? Gone. The fog of unreality? Slightly thinner.

Lamotrigine was stabilizing my thalamocortical oscillations—allowing parts of my brain to communicate again. Areas like BA31 (posterior cingulate) and BA24 (anterior cingulate)—once dimmed—began to flicker back to life.

But Lamotrigine alone wasn’t enough. My breakthrough came when I added Memantine—an NMDA receptor antagonist typically used in Alzheimer’s disease. In my case, it wasn’t off-label—it was precise. Memantine didn’t just suppress symptoms. It completed the system.

Where Lamotrigine modulated presynaptic glutamate release, Memantine regulated postsynaptic NMDA receptor activity, creating the quiet, low-noise environment necessary for functional restoration.

The Glutamate Clues Psychiatry Missed

My turning point came when I saw that no single study held the full answer—but several, when integrated, did.

Rodolfo Llinás (neuroscientist) showed that NMDA receptor dysfunction can destabilize the thalamocortical rhythm, producing the exact “disconnection” signature seen in my qEEG.

Gary Parsons (neuropharmacologist) demonstrated that low-dose Memantine can stabilize NMDA receptor activity.

Stuart G. Cull-Candy (synaptic physiologist) revealed that, during recovery, NMDA receptors shift from their immature NR2B form to the mature NR2A configuration, improving signal precision.

In parallel, Chun-Yao Lee (pharmacologist) and colleagues showed that Lamotrigine inhibits postsynaptic AMPA receptors and reduces glutamate release in the dentate gyrus—quieting excess excitatory activity without impairing normal signaling.

Clinicians like Dirk De Ridder (neurosurgeon) and Sven Vanneste (neuroscientist) have already shown through qEEG research that thalamocortical disconnection has a measurable electrical signature—one that aligns precisely with what my own scan revealed.

Combining these insights produced a coherent protocol: Lamotrigine to suppress AMPA/kainate overdrive, Memantine to stabilize NMDA receptors, and time for natural receptor maturation.

Addressing all three major glutamate receptor subtypes—NMDA, AMPA, and kainate—restored balanced excitatory signaling, essential for re-establishing thalamocortical coherence.

This was a patient-led synthesis of four independent neuroscience frameworks into one functional treatment—and it worked.

The Brodmann Circuits Reawakening

Once this cord was restored, the thalamus could finally re-engage to the cerebral cortex. It began to power on the Brodmann circuits — BA31, BA24, BA7, BA41/42, and more — allowing sensory information, self-awareness, emotional tone, and spatial mapping to flow again. And from there, my brain began its return to homeostasis.

The Brodmann circuits that came back online:

BA31: Sense of self, time, derealization (posterior cingulate)

BA24: Emotional regulation and attention (anterior cingulate)

BA7: Spatial awareness, proprioception

BA41/42: Auditory processing, language integration

BA6: Premotor planning and action initiation

BA10: Executive function, future planning, multitasking

BA13: Insular cortex — interoception, emotional salience

BA9: Working memory, social reasoning (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex)

BA8: Eye movement planning, decision making

BA39: Language comprehension (angular gyrus)

BA40: Multisensory integration, speech production

BA46: High-order executive attention

BA11: Social emotion processing (orbitofrontal cortex)

BA20: Visual memory, object recognition

The DSM Failed Me — But My Brain Didn’t Lie

The field of psychiatry is still dominated by the chemical imbalance theory, even though modern neuroscience has long since moved on. They throw SSRIs at anything that looks like sadness. They throw antipsychotics at anything confusing. They throw diagnoses like darts — hoping one will stick.

But what if the issue isn’t serotonin? What if it’s glutamate and electrical synchrony? What if the problem isn’t “mood” at all — but a misfiring thalamocortical system, disrupting circuits like BA31 (self), BA24 (emotion), BA41/42 (sound), and BA7 (space)?

That was my case. And I have qEEG data to prove it.

My circuits weren’t emotionally blocked. They were electrically disconnected.

We Need a New Diagnostic System — One Based on Brain Maps, Not Labels

It’s time to retire the DSM as the gold standard.

It’s time to stop calling things “treatment-resistant” when we haven’t even mapped the brain.

The future of psychiatry isn’t in more labels. It’s in qEEG, neuroimaging, and AI-guided pattern recognition. It’s in matching symptoms to circuits — and using that map to reverse engineer recovery.

I’m not a doctor. I’m a patient. But I solved what six psychiatrists could not. Because I used neuroscience, not trial and error. Because I listened to my brain — not their model.

I am living proof that psychiatric misdiagnosis can steal years from a person’s life. I am also proof that a brain — even a broken one — can be rebuilt.

Oh wow, what an interesting mind this one has. Only mad people like me and him can sound as delightfully mad and sane as this. Probably you might be right with all your theories my friend and if I was a psychiatrist, I wouldn’t be betting against your suggestions. But honestly, it doesn’t seem all that important to me what the brain is doing. Whether an explanation would involve serotonin receptors or neural circuits doesn’t alter a thing about the actual problem which takes place within consciousness, and can be understood only there. If your theories are correct, they are based on your own conscious observation, so the truth is clearly, manifestly, undeniably that the only cure for all human ills including so called ‘mental illness’ is in consciousness, not in the immeasurably complex and perplexing functions of the galaxy of neurons we call the brain. But perhaps that fantastically complex brain produced all your theories from inspiration. I can’t judge, especially not a brain that is as quirky and creative as yours.

Report comment