In a new article published in JAMA Psychiatry, researchers found no neurobiological difference between those with the depression diagnosis and those without. However, social-environmental factors were a powerful predictor of depression.

The “Key Points” for the paper sums up the neurobiological failure quite well:

Question: What is the neurobiological difference between healthy individuals and those with depression within common neuroimaging data modalities?

Meaning: Study results suggest that patients with depression and healthy controls are remarkably similar regarding neural signatures of common neuroimaging modalities.

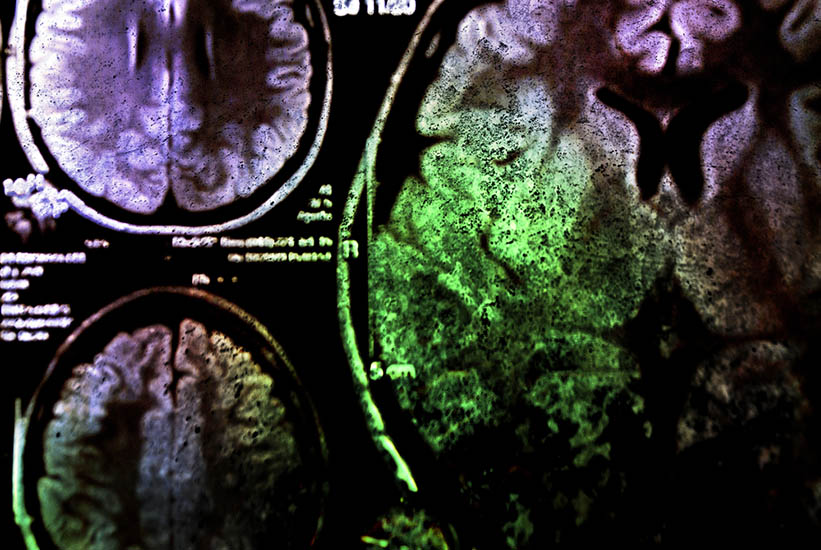

The study included 861 people with the depression diagnosis and 948 “healthy controls.” The researchers included every major neurobiological measure: “structural MRI, task-based functional MRI (fMRI), atlas-based connectivity, and voxel-based physiological and graph network parameters derived from resting-state fMRI and diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI),” as well as the polygenic risk score (PRS). Finally, they included environmental variables, including self-reported childhood maltreatment and social support.

The study included 861 people with the depression diagnosis and 948 “healthy controls.” The researchers included every major neurobiological measure: “structural MRI, task-based functional MRI (fMRI), atlas-based connectivity, and voxel-based physiological and graph network parameters derived from resting-state fMRI and diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI),” as well as the polygenic risk score (PRS). Finally, they included environmental variables, including self-reported childhood maltreatment and social support.

All of these biological tests were non-significant at p < 0.01 once the researchers controlled for the fact that they conducted so many statistical tests (which increases the likelihood of chance results).

Even if the non-significant tests were all included, the neuroimaging “signatures” explained less than 2% of whether someone received a diagnosis of depression or not. The accuracy of using neuroimaging for identifying whether someone had the diagnosis or not, “even under ideal statistical conditions,” was between 53.5% to 55.6%. (For comparison, 50% would be guessing based on a coin flip.)

The PRS—a measure of all the possible genes that have ever been theoretically linked to depression—had an accuracy of 58.3%, slightly better than every neuroimaging test but, again, not much better than chance.

In contrast, the social-environmental variables “social support” and “childhood maltreatment” were significantly linked with depression, and each predicted with greater than 70% accuracy.

The researchers did not test other social-environmental variables, (e.g., trauma, sexual abuse, physical abuse, recent loss of a job, loss of a spouse, economic insecurity, bullying). It is likely that these other variables could be added to the two that were tested to substantially increase the predictive value.

Of note, the abstract, discussion, and conclusion sections of the paper do not mention, even in passing, the much higher predictive value of social-environmental factors.

The researchers theorized that “clinical heterogeneity” might be the problem behind their lack of results. According to that theory, there are some small groups of people who do have brain differences, but because “depression” is such a catch-all diagnosis, the data from those few people are drowned out in the “noise” of all the rest.

For that reason, they conducted a variety of subgroup analyses, separating out those with chronic depression, those with acute depression, and those on medication, for instance. However, none of their analyses turned up a significant finding.

They write, “Extensive subgroup analyses revealed that clinical heterogeneity alone is also not concealing potentially relevant differences.”

In the end, though, rather than argue for the importance of social-environmental factors in explaining depression, the researchers double down on neurobiology. Their conclusion does not even mention the high predictive value of environmental factors, instead focusing on how future research must improve neurobiological testing:

“We recommend the following: (1) all researchers should clearly communicate the relevance of their findings by reporting measures of predictive utility or distributional overlap in addition to P values; if predictive utility cannot be demonstrated, researchers should precisely state in what way a significant effect advances the development of a quantitative neurobiological theory of depression, and stake holders may want to consider novel approaches to fMRI paradigm design; (2) the community should prioritize more comprehensive phenotyping, including deep phenotyping of existing cohorts, the systematic assessment of novel digital phenotypes, moving beyond simple case-control designs, as well as longitudinal assessments of symptom dynamics and life events; and (3) the major issue of poor predictive performance needs to be addressed; machine learning approaches are increasingly used to investigate multivariate patterns of deviations and map high-dimensional biological information to complex phenotypes.”

The research team included 31 cross-disciplinary researchers, including neuroscientists, geneticists, and computer scientists. They were led by Nils Winter at the University of Münster, Germany.

Their research is consistent with a recent paper by the second most influential neuroscientist in the world, Raymond Dolan, who wrote that “psychiatry’s most fundamental characteristic is its ignorance, that it cannot successfully define the object of its attention, while its attempts to lay bare the etiology of its disorders have been a litany of failures.”

In an editorial accompanying the study by Winter et al., Lianne Schmaal of the University of Melbourne writes,

“From a clinical perspective, these small effect sizes make it unlikely for individual brain measures to provide diagnostic biomarkers. This begs the important question of whether we should continue to pursue the identification of clinically useful neuroimaging markers for depression, and if so, how?”

Schmaal suggests including social-environmental factors in neurobiological measures in the future:

“Perhaps more promising for diagnostic classification purposes is combining neuroimaging measures with environmental measures such as childhood trauma and social support, which were found to explain more variance in the depressive phenotype.”

It is unclear what the neuroimaging measures would add, since, again, the research team found no significant results.

Schmaal leads the two largest neuroimaging groups worldwide, ENIGMA-MDD and ENIGMA-STB. She is also head of a program using machine learning, neuroimaging, and genetics data at the non-profit Orygen.

Editor’s Note: Mad in America previously covered this study when it was posted on the open-access website arXiv, but it has now appeared, revised and with an editorial comment, in top-tier psychiatric journal JAMA Psychiatry.

****

Winter, N. R., Leenings, R., Ernsting, J., Sarink, K., Fisch, L., Emden, D., . . . & Hahn, T. (2022). Quantifying deviations of brain structure and function in major depressive disorder across neuroimaging modalities. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(9):879-888. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1780 (Abstract)

Schmaal, L. (2022). The search for clinically useful neuroimaging markers of depression—A worthwhile pursuit or a futile quest? JAMA Psychiatry, 79(9):845-846. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1606 (Abstract)

Is not a delusion defined as persisting in a belief against repeated and incontrovertible proof of invalidity?

Report comment

Kind of like insanity being defined as trying the same thing again and again and expecting different results.

Report comment

Yay, Peter! Keep up the good work! How I wish the New York Times and every other thing people actually read much had the courage and honesty to publish this sort of article.

Report comment

Devastated. 3 generations of trauma and abuse in my family. Lives fully destroyed. After being told my whole life that I’m “mentally ill”, ECT, drugged, locked up, mocked. No answers, no hope. Just hide away until it’s over so they don’t get there hands on me again.

The people who allowed this travesty to go on for so long should be deeply ashamed.

Report comment

There seems to be a trend: Researchers find that various psychiatric drugs are ineffective, or that biological explanations for mental health issues don’t hold up. But instead of facing reality as a sensible scientist should do, they deny their own findings and double down on their pet theories or mainstream beliefs: If only we keep looking, we’ll find the thing we believe exists! THIS is madness.

Report comment

It sure isn’t science!!!

Report comment

Isn’t the foundation of science the ‘null hypothesis’ meaning that you start by disproving a theory and only after many failed attempts does a theory become valid. It seems to me there are many studies dating back decades supporting the statement ‘antidepressants do not relieve depression.’

At what point can we no longer consider psychiatry, and even modern medicine as a whole, a hard science?

Report comment

Exactly. A “true” finding should prompt a forceful attempt to disprove it. Only after vigorous efforts to come up with any and all reasonable alternative explanations and finding them wanting is something “true,” and then only until any further data that brings the “true” datum into question. Psychiatry certainly does not operate that way, never has, and most of Medicine is similarly plagued with favorite theories and beliefs that are untested or are believed because that’s what everyone believes, not because of any intent to find the actual truth.

Report comment

https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/12/health/ketamine-infusions-help-depression-study-wellness/index.html

How are they still able to get the media to do their bidding and publish articles like this (in which it’s stated that despite ketamine being proven effective, it hasn’t matched the remission rates of ECT. What?). This should be illegal. 6 years ago they were “reporting” the same things about TMS.

Maybe not insanity if the real goal — keep making money — is being accomplished.

Report comment

We all judge and that is what psychiatry does. It simply took over whatever society had in place to lord over all those “other” people.

Isn’t it wonderful that I can go to a shrink and say “i’m depressed”, and he diagnoses me saying “you have depression”.

Similar to me going to a priest with my confessions and the priest telling me I’m a sinner.

Report comment

I’d like to see them separate out scans from the medication naive from those with a medication history. Then break it down further based on the number of drugs a person was exposed to, type of drug, and length of exposure. The term ‘treatment resistant’ is used to justify increasingly invasive treatments when in reality they still can’t say that ‘treatment resistant’ isn’t acrually ‘treatment caused’ depression.

Report comment

You know what? I was a math major at Harvard. And, I suppose it’s not considered polite for me to go and say that it was more than just being a math major at Harvard. I was something of a genius in a unique way compared to most math majors at Harvard, though that did not necessarily mean I always did well, because my brain needed the right social conditions to fully work right in math, and I usually was deprived of those conditions, but those few times I had them, it was amazing. I should probably just be accurate, right?

Anyway, this article reminds me of the debate over gender differences in the brain. Where, actually, fMRI’s have found only very tiny visible differences, and then feminist professors have decreed that we need to default to the politically correct viewpoint of “all gender differences are socially constructed and not biological” in the absence of evidence. Or, in the instance of evidence showing that, what gender differences can be SEEN that way appear tiny, then we argue gender brain differences are tiny.

The politically correct dogma viewed as a religious decree which is supposed to impose on science. When, in fact, a true scientific approach is merely to say that, in the absence of proof, “we don’t know one way or the other.” Rather than, if you are WITH political correctness, what you say gets to be regarded as automatically true and you don’t have to prove it. if you go against political correctness, you have to prove it first — and then, even proving it is often not enough, in practice.

Anyway, this all bothered me a lot because, actually, I think this whole question could be solved by mathematicians. My mathematical intuition — which was especially good with geometry — tells me that, even if there are major brain differences with both gender and depression, that our ability to visibly see them using these MRI techniques is always going to be very circumscribed.

Because, unlike the rest of our body, the brain is a very specific and complicated geometric shape, and is encased in a skeleton that is hard and also is a specific and complicated geometric shape. Now, in our bellies or muscles like biceps, we can gain weight and the fat makes them bulge out, or we can gain muscle and get stronger, and our muscles bulge out and we can see them more.

Well, I think that when we specialize in one particular skill rather than another, this changes the balance of our brains, making certain parts slightly larger and others less large, just like it is with muscles, and gender brain differences as well as differences between the depressed and non-depressed might manifest in a slight size difference. But that means the brain activity for a particular “skill” cannot be concentrated in any one area, as this will cause that part of the brain to enlarge like a tumor, destroying the geometrical precision of how and where it fits into the rest of the brain, or the skull. And this means that brain activity must be distributed across the brain, sort of like a super disorganized tangle of yarn.

Because, the brain doesn’t know what it is going to have to learn, when it grows up, or I should say it doesn’t know what it’s going to have to specialize in. It has to ensure that, as you intensively specialize in a particular skill, there is never so much activity concentrated in one geometrically small spherical area of the brain, so that this part of the brain grows like your bicep muscle might with weight lifting, only to crowd out adjacent portions the way a tumor might.

This means the neural activity, for the brain “specializing” in one thing rather than another, as in being different from the average or “blank slate” non-specialized brain structure that is genetically determined, will have to ensure such “specialization” or “difference from the norm” as it determined either by a differently learned skill or by the action of testosterone rather than estrogen on brain development, will have to ensure that such specialization differences in neural volume will have to be distributed over distant parts of the brain, parts of the brain quite distant from one another, in such a way so it’s all a small amount of brain expansion evenly distributed so as not to have a tumor effect or bulge in the wrong area.

And, by the way, computer scientists creating hard disks for information storage have to do the same thing — create algorithms to ensure the data is distributed in lots of little specks evenly over the whole entire disk, or they’ll run into the same problem.

Also remember, in the case of gendered brain differences, most of the DNA that makes up the female brain as compared to the male brain is exactly the same, meaning it encodes the same geometry in women as in men. And there is no choice on that. It’s already a super complicated math problem, for the limited amount of DNA we have, to successfully encode ONE brain of a successful geometric shape with no encroachment and everything fits together perfectly. To create two different male and female brains involving radically different geometries would require that we all have something like maybe twice the amount of DNA in humans, all of which can’t overlap between males and females. Because if it did, you’d end up with babies born where the DNA was trying to fit square pegs into round holes too much.

Thus, male brains are — mostly — just female brains which were allowed to grow bigger. And maybe the hormones created differences in the pruning of neural connections, within the same geometric brain shape. That already means, a gendered brain difference pretty much would have to be somewhat similar to a two mile high long lightning bolt, taking a slightly different two mile path and striking the ground only six feet away from where it otherwise would have.

Can we, looking at binoculars ten miles away, at a two mile long lightning bolt, notice a six foot difference in where it lands on the ground? And yet, let’s say there are two lightning rods on the ground at both locations, six feet apart. Understand that the lightning, as an electrical circuit, hitting one lightning rod rather than the other could result in an astronomical difference, depending on what those two different lightning rods are connected to. But it all looks the same to us.

The same thing could easily apply to the depressed brain, as compared to the non-depressed brain. Let me see, what would a mathematician say? IF the differences between a depressed brain and a non-depressed brain were big enough for us to be able to see in this way, then the non-depressed person’s increased brain activity would stimulate those parts of the brain we can SEE to grow enough neurons until non-depression starts creating too much pressure on adjacent parts of the brain like a tumor. BUT, because the brain has figured out how to rout all the brain activity just right so as to guarantee against this happening, that means we cannot see the difference between depression and non-depression, with such crude measuring techniques.

Now here is where my ADHD and brain injury start to take hold. I say this as mathematical “insight,” but in terms of thinking it through, I can’t do that right now and maybe I don’t have sufficient information to know how to think it through. But it is true that neurologists should network with pure mathematicians and/or physicists or both.

Because I am pretty sure a pure mathematician could, after a bit of work, explain/predict that brain differences with depression versus non-depression, as well as gendered brain differences, are going to be impossible to detect with these kinds of studies. And they are capable of predicting all that theoretically, in the exact same way as Einstein eventually predicted black holes, theoretically, and only after he predicted them were they able to take the science he developed, and then figure out how to INDIRECTLY measure and “prove” that black holes really existed.

I think a similar type of mathematician could do the same kind of work Einstein did, and eventually figure out theoretically how, IF gendered brain differences and brain differences with depression — and depression is gendered so it’s good to look at both of them at once — existed, then exactly HOW can they manifest in the brain, in such a way so as not to disturb the underlying brain geometry, as well as other constraints. And then, and only then, do you know what to look for.

A mathematician might even find that they theoretically could exist but current technology is incapable of producing measuring instruments capable of reliably measuring the differences. How long after Einstein did we discover the first black hole?

Report comment

I thoroughly enjoyed reading that!

I think the worst delusion I’ve ever had was how thought antidepressants were developed when first given them as a teenager. I thought they new every single side effect because they attached radiological tracers to the drug and were able to watch exactly how and were the drug worked. In the process I thought they identified every possible side effect and knew exactly why it occurs. If the side effect wasn’t on the list then it couldn’t possibly be caused by antidepressant and must be my fault and not the drugs fault.

Man was I disappointed when decades later I realized it wasn’t as much rocket science as it was paper airplane folding.

Report comment

They couldn’t find a discernible difference because the technology to do so does not yet exist. It may never exist.

What is the correct brain that we should be measuring other brains against? Most would snap back without thinking it through that a correct brain would be owned by a non-depressed person.

Non-depressed where? Probably on a campus at a wealthy University in the West.

And then what would that prove?

Well, no-one dare say lest they come across as a bit of a Communist.

So what shall we say instead? Anything other than that all depressed and non-depressed brains appear to be much the same according to current technologies because everyone is fundamentally, deep-down, depressed. Some have found ways to hide, mask and avoid their deep-down depression. They are then chosen to control the machines to scan the people that have lost or never gained the ability to hide or mask their depression.

Sensibly, what depressed people truly need — and probably all of the planet needs too — is for all of the non-depressed people to give up their masks and allow themselves to be depressed too.

What kind of fool is able to maintain a sense of happiness and inner peace in times like these?

Report comment

Hmmm… 2% vs. 70%… which seems to have more effect, neurology or life experience… tough one…

Report comment