As a preteen he had a big hairy mole on his neck and that was the first thing I noticed about him, though he had it removed early on. In his earlier years he was on the chubby side and in his later years on the skinny side but what remained the same was he made everyone laugh. He told me when he was skinny and quiet girls liked him more because he was more mysterious than when he was heavier and talked a lot. In my earliest memories of him on the office porch or waterfront steps at Sandy Island, he was laughing about something, making fun of something, and that something usually included himself. He liked to make fun of Jews, which we both were, and of course our families. I can still hear him making fun of Mama Bloom and “Mama Grossberg” as well as “Papa Grossberg”.

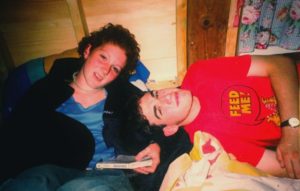

As teenagers Michael and I both primarily had “friend” status with the opposite sex. I thought I was too skinny, he may have thought he was too chubby. There were other reasons, far more complex than body type for why we both remained virgins until college. To the girls, he was the one we most wanted to talk to, but least wanted to kiss. He had his crushes on most of us, but none seemed too serious, and perhaps, like me, he enjoyed “friend status” where conversations were often more interesting and everything felt a bit more sane at that age. I’m not sure which came first, his nickname Sugabear or his “perverted gesture” which was basically lifting up his arms and thrusting his pelvis. We girls would ask him to do it over and over, never getting enough of it, cracking up every time. Finally he refused to do it every time we asked for fear it would lose its novelty, but I’m not sure it ever did.

It was August of the summer before my first year at college so he was 19 and I was 17 when he came into my cabin and woke me up to watch the sunrise. His idea the night before, others were supposed to be woken up too, but no one else would get out of bed, so it was just me and Michael Bloom. Silent except for lightly crashing waves of Lake Winnipesaukee and morning ducks, we sat on the wooden waterfront chairs resting our arms on the arm rests as the sun bounced off the lake and hit us in our faces. Late August in New Hampshire the sun was warm even at 5AM, 6AM…by 7AM we could hear the sounds of kids being ushered to the bathrooms by parents mildly hustling to get everyone’s teeth brushed amidst Daddy Longlegs and muddy boot trackings on the bathroom floor, which could only stay clean for the first family.

But hours before the hubbub, Michael and I only saw the gleam of Lake Winnipesaukee, only heard the light waves, vocal ducks and each others voices talking about what it was like to go to college a virgin and feel like the only one. The warmth of the sun on our faces made everything okay. The fact that it was silent except for us, the only 2 who followed the plan to wake up before sunrise since it was our only week together all year and though the days were long, filled with time to roam, the week was never long enough and before we knew it it would be over. We’d be back to our ordinary (or not so ordinary) lives where different rules applied and there wasn’t a perfectly quiet lake to sit by with a friend we’d seen every summer for as long as we could remember summers.

Michael valued Sandy Island above all else, for it was where there was time to dream, meander, cry, have adventures…all in a timeless bubble, yet it seemed to create a time capsule by being repeated each year….a thread woven through our lives. It was just one week a year, or two for some families, yet one week on an island can feel like eternity-until it ends. It can feel like a timeless place where what you discuss floats along the tide, the lake whispers things to you. You may not know just who it is you are talking to or what they wear in their everyday world, but you know for the moment you are lifelong friends, you know this is important, to carve out time away from everything else to ponder mysteries, act out rebellions, make up jokes, give everyone a strange nickname, and laugh as the sun bubbles up.

In college at Rutgers, Michael met Andrea who he called “The Big A” and developed a romance with. Their connection was strong enough that she tried to contact him in recent years, nearly 15 years later! Sometime in his first few years at Rutgers, Michael had some experiences ranging from joyful ecstasy for his new connections with people to utter despair at the state of the world. These were on the continuum of what many young adults touch upon as they come to know the freedoms and burdens of adulthood, yet he experienced them in a more extreme way than some do. Or perhaps he just had the courage to admit it. I certainly had my own extreme states of awakening and despair at a similar age, and similarly experienced them in heightened way.

I visited him at Rutgers where he was sociable and excited about connecting with just about everyone we passed in the hall. This was different from high school where he had a small group of friends and didn’t socialize much outside of it. In college he seemed high on life, on meeting new people and engaging with everyone he could. These states were sometimes followed by states of despair at the state of the world, which led to a suicide attempt and landed him in the hospital.

“Life on Lithium is totally boring,” he told me after that, “but it saved my life and I may need to be on a small dose of it for the rest of my life.” He said many times that without it he could become suicidal again, which clearly was not a risk he was willing to take and it was hard to argue with that. “On Lithium, I don’t feel the highs and excitement I used to feel, but I don’t feel the lows as much, so it’s keeping me alive.” In the years to come whenever I suggested the Lithium could be causing some of his problems (apathy, boredom, constant unhappiness, being disinterested in everything and sometimes unable to connect with people), he would come emphatically back to this exclamation, “Lithium saved my life,” angry that I didn’t seem to get how true that was for him. Despite that we were both raised by East Coast Jews who put Western medicine on a pedestal, we took very different paths to address our “mental health” and sometimes seemed to have opposing views.

Michael’s mom was a nurse and his father a professor of science or history (I forget which). My mom was a math teacher and social worker and my father a dentist. My parents had a hair more skepticism of psychiatry, for my father became a dentist rather than another type of doctor in part so he’d be less influenced by pharmaceutical company corruption and my mother was trained as a therapist before the Prozac-is-aspirin years. She had an uneasiness about drugging mental distress from the first time my therapist referred me to an expensive psychiatrist when I was 15.

I steered away from allopathic doctors, not trusting them and I was a seeker of the alternative early on. In my teens I became vegetarian, practiced yoga and meditation (which I first learned from books, then classes) and stopped taking the Prozac my therapist recommended. In college, I studied herbalism, nutrition and everything I could get my hands on about alternative healing and spirituality. From a young age, my spirituality was connected to my body, my breath, what I ate or consumed, what surrounded me.

Michael’s interests and path were entirely different, though not incompatible with mine for he had a passion for art and philosophy and was one of the biggest dreamers I knew. Yet, over the next 10 years, he seemed to gradually decline in energy levels, happiness, aliveness and functionality. I saw him at least a handful of times in these years, for his brother went to school in the same town as me, and he visited us every so often. On one nighttime visit when I was still in college we walked around the cemetery in Amherst, MA, where Emily Dickinson was buried and he asked me if I’d marry him someday, if we were both single when we were 30, or something like that . We were disagreeing and debating and he commented that we sounded like a married couple-a married East Coast Jewish couple like our parents, anyway.

On another visit he came to a Freedom Center Northampton meeting with me. At this time I was withdrawing from the cocktail of psychiatric drugs I’d been put on the previous year and having insomnia. He asked skeptical questions about the Freedom Center, how people “like us” lived without psychiatric drugs, and we had many debates on the phone about mental health diagnoses, the pharmaceutical industry, what we believed. These disagreements were both meaningful and frustrating for me. Michael said that he had bipolar and a lot of people were pressuring him to just get a job or go out, get out of his own mind, but they didn’t get that he had a real illness that actually limited him the same way a physical illness can.

Although this was not exactly my explanation of him (I saw him as a sensitive, hilarious genius with unlimited potential stuck in a rut due to Lithium, an indoctrinated limiting view, a sick society which upset him, not enough support and a number of other factors), it was when he tried to define me in a similar framework that I could not stay silent. Mike frequently asked me what my diagnosis was and whether I was taking anything, which was bait for the fat fish of my own story.

At around the same time as Lithium was credited with saving his life, the drugs I was on (Risperdal, Buspar, Effexor, Ambien, Prozac and Xanex) nearly killed me and rendered me unable to think, function, or even move much of the time. I told Michael this many times, along with sharing my lack of belief in diagnoses, how they never helped me understand myself or the world better, and emphasized diagnoses were created to sell drugs, which he couldn’t argue with. Sometimes once we got that far in the conversation, he seemed humbled a bit and perhaps relieved.

Still, I was the only person in his entire world who believed the Lithium was harming him or even questioned its efficacy. He told me sometimes all he could do was chain smoke and watch movies, but there also came a time when movies no longer did it for him and there was nothing. He lived in Hawaii for a few years, but hated it and returned to live with his father in West Newton, MA until his suicide in 2012. He had various jobs over the years from being a mailman (which was one of his childhood dreams!) to working in the census office, and in Hawaii he volunteered at a museum. In the few years leading up to his death, he went to DBSA meetings (Depression Bipolar Support Alliance which is a pet of Big Pharma that “supports” the medical model view and unquestioned psychiatric labeling) but felt no one there was smart enough for him and they were too entrenched in the system. I imagine they were highly drugged, more so than Michael.

When he returned from Hawaii, which was several years before his suicide, his mom developed tinnitus, ringing in the ears, that was unbearable to her, Michael told me. This led to her suicide in 2008. I couldn’t help but wonder if she had been psychiatrically diagnosed and drugged and if the drugs had been a contributing factor, or even the primary cause of, her suicide. I was still living in Northampton, MA (sister town to Amherst) at the time without a car, so when I got the call about Mama Bloom I booked a bus ticket to Boston right away. Michael and I hadn’t seen each other since before he had moved to Hawaii, so it had been quite a few years and he had been hard to reach by phone that summer.

When I saw him at the funeral my heart rushed open and I cried; we both cried as we embraced, my heart so full of love for my old friend. He looked and felt better than I’d expected him to and he later told me how good it was to have family and friends around but how hard it was when they went back to their busy lives weeks later. Michael’s younger brother read something Michael had written about their mom at the funeral, which made me so proud of who he was. I realized also that he was surprised and moved that I had come as I was the only non-relative who traveled from outside the Boston area to come, although I was only 2 hours away. It was that moment when we hugged under the canopy, next to the rabbi, that I felt the true meaning of friendship-of being part of someone’s heart and knowing your presence does in fact make a difference. And what a difference that made to me!

Michael held friendship as one of the highest values in life, higher than work or even marriage, it seemed. He frequently told me how disturbed he was by our society being so isolated into couples and not staying loyal to friends much of the time. Though there were a couple of time he expressed interest in being more than friends with me I never felt that get in the way of our friendship as it seems to with many others. I never felt awkward or like he needed more.

Over the years following Mama Bloom’s death, Michael seemed to sink deeper into despair and then apathy. Frequently his phone messages were in a flat tone and said, “I hope you are okay.” He could no longer say “I hope you are good.” for being good, or anything beyond okay was no longer in his frame of reference. There were countless messages from him saying he hoped I was “okay,” and the way he said “okay,” I knew he was striving for just that.

He also told me the shrinks were changing around his drugs and adding more. They added an antidepressant or two to the Lithium and increased doses and eventually he seemed to have very little life left in him. Our phone calls became trying for he was so down, practically dead sounding a lot of the time, and I felt unable to do anything or say anything to make a difference. To even try felt futile and I wondered if talking to me at all was becoming the burden of yet another person he couldn’t connect with.

In the early years, he liked to think of us as being in the same boat, both “mentally ill”, since I’d also had a meltdown and I also am extremely sensitive. But as the years went by, especially towards the end, I seemed to be in the ever growing “other” camp in his eyes, which meant I was yet another person who didn’t get what it was like to be him. And at that point I can confirm I did not, and perhaps did not want to.

When Bobo, Mike’s brother, called me one morning and left a voice mail saying there’s something he needed to tell me, I was on a walk and on the other line talking to my friend and coworker Jenny. Since Bobo doesn’t call me ordinarily I knew it couldn’t be good news. I had called him once several years earlier when I was concerned about Mike, after we had a big argument-perhaps our biggest ever. It had to do with his time in Hawaii and I was at Sunset Beach in San Francisco feeling lonely. Michael had yelled at me and gotten enraged about how horrible Hawaii was. He compared California to Hawaii and said he hated that culture, hated the people on the West Coast and kept asking when I was coming back to the East Coast, when I was coming back to my real home. I had no intention of coming back to live on the East coast again, ever, once I moved to the West Coast. I got angry that he asked me that every single time we talked, since I was lonely and wanted to talk about other things, like what was actually going on in my life, and his.

Something in me knew what Bobo was going to say. When we got off the phone (all I had said was “Oh My God” over and over-like the opposite of an orgasm) my pulse was racing as I walked through the Whole Foods parking lot back to my car. I had an acupuncture appointment, should I go? The idea of being physically alone was too daunting so I went. Katie said my pulse was rapid and it had never been rapid before in our 5 months of weekly sessions. I cried on the table and finally blurted it out, “One of my closest lifelong friends just committed suicide. And I just found out.” The small room seemed filled with his spirit and I swung between feeling the despair he must have felt and the joy and liberation he must have felt. I saw him dancing on clouds with kiddie-boppers (his endearing term for children) and I saw him cutting his wrists in his basement.

When I got home that day I didn’t leave my house for 2 whole days. I texted everyone I could think of and asked friends to come visit me the next day since I couldn’t bring myself to go out and I could not be physically alone. All night the image of bloody wrists haunted me. Bobo had asked if I was sure I wanted to know how he did it and I’d said yes- I knew I had to know. That night I called my mom around 1am, 4am her time in New York. I cried and told her over and over how freaked out I was. She said she had to get off the phone, asked me if I had a Valium I could take to get to sleep but I said “NO, I need you to listen to me.” Strangely, she didn’t remember Michael, though they met in New York when he visited and she had made an impression on him, with her thick Bronx accent, which he carried with him and mimicked from time to time.

The following day was Friday and Jenny and Nina (my oldest friend, who I have known since I was a few weeks old) came over with pastries and coffee. We sat in my yard in the sun and I talked about everything I could remember about him: tidbits of memories like his favorite song (America by Simon and Garfunkel), his favorite line in it (about the New Jersey Turnpike) and the Billy Joel song that played in the car the last time I saw him (You May Be Right) and how I used that song to defend myself when he made fun of my personality. “You may be right, I may be crazy, but it just may be a lunatic you’re looking for.”

Later CJ came over. We said a prayer holding hands and spoke to his spirit. After that I felt more ease and eventually he came to me in a waking dream state and told me death is like an airport-you go into different terminals and resolve things, come to understandings with all of the people in your life and you fly to different places. Gradually the tormented feelings I’d had faded, as did the “high” feelings, where I experienced the world as he did in his most passionate moments.

I told Michael I loved him once or twice and he responded, “Do I have to say I love you too?” I said no, and didn’t feel hurt. On a walk the other day, I thought of the cliché, “It’s better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all,” and decided it was true. I actually had to think about it, considering how painful loss can be, but nonetheless it must be true.

Chaya Grossberg has been working as an activist for change in the “mental health” system for over 10 years. She is a writer, teacher and group facilitator living in Portland OR.

This is one of the saddest and most aggravating things to ever experience; that is, watching someone you care about and love go downhill almost on a daily basis. For some reason, they accept the quackery and flim-flammery of biopsychiatry and the drug companies and insist that they are incurably sick and must take the toxic drugs. You dread the day in the future when you get that “call” letting you know that your loved one is dead. It makes me furious, not at the person but at the system and the drug companies that have orchestrated all of this on purpse so that they can make their billions of dollars every year.

Report comment

Chaya, this is one of the most moving and beautifully written memoirs I have ever read. Thank you for posing this, and I am looking forward to reading more of your writing.

Report comment

Posting, not posing. Sorry.

Report comment

Thank you for telling the story of you and your friend.

Report comment

Thank you!

Report comment

Psychiatry lied. And people died.

This could have been me. The poor guy. And to think he had so much exposure through you, to alternative mental health.

The faith in psychiatry’s quackery was strong, strong enough to suck him into the vortex of hopelessness.

I believe millions have died in this way.

I find it a little unsettling that his mother couldn’t say goodbye or that he had to deal with his mother’s sudden passing. That is horrible.

What about his Dad? All alone, wife dead, son dead. What a horrible situation.

Report comment

This site is awesome for publishing this.

Report comment

Thank you Chaya for sharing this moving and all-too-common story. None of my friends who were tied up in the system at an early age have yet successfully committed suicide. None of them seem to be to be particularly thriving either. Perhaps this story and the thousands of others like it will help people see that a bigger view than the “medical” model is needed.

Report comment