Following is the second part of a two-part series on Rethinking Mental Health. While it’s not necessary to read the first part (Rethinking Mental Health, Part 1: From Positivism to a Holistic/Organismic Paradigm) in order to understand this one, doing so will probably provide you with a fuller picture of this piece.

Part One:

Towards a Needs-Based System of Diagnosis

When we look closely at the current mainstream diagnostic and support system for so-called mental disorders today, the utter absurdity of it quickly becomes apparent. We have a system composed of literally hundreds of discrete “mental disorders” (those listed in the DSM), all of which are believed to be the direct result of soon to be discovered brain diseases, in spite of the fact that no reliable biomarkers have yet been found for any of them after a century of intense searching, a fact acknowledged just last month by the current designer-in-chief of this system himself. The disorders listed in this system have literally been voted in by a behind-closed-doors panel, the majority of whom are either directly or indirectly funded by an extremely powerful drug industry whose profit is derived directly from this system. And this system, as artificially crafted as it is, affects the lives of millions, arguably billions, of people all across the globe, creating a world in which many millions of people are placed on very powerful mind altering, aliveness dampening drugs for their entire lives in many cases, while genuine needs-based systems of support are tragically swept away. There’s no doubt about it—this enormous atrocity is the direct outcome of our positivistic thinking, combined with an essentially unbridled capitalistic system which itself has been shaped and fueled by positivism. There is, however, some hopeful news, in that a holistic paradigm such as the one presented here offers the possibility of a far simpler and more effective system of diagnosis and support.

In spite of the enormous complexity of living organisms, the issue of health is actually relatively simple when we consider it from the perspective of the holistic organismic paradigm being presented here. Optimal health is the default status of all organisms whose needs are adequately met, whether the organism be a single cell, a plant, a dog, a human being, a family or an entire society; and reduced health and even death may occur when these needs are not being adequately met. It’s really as simple as that. All organisms, by their very nature, have a strong desire and ability to maintain their existence and to work hard to meet their needs. Nothing special has to be added—there is simply nothing more natural than healthy existence. However, because organisms do have a lot of needs (and the more complex the organism, the more complex the needs), it’s nearly impossible to get through life without running into various obstacles to meeting these needs, obstacles I will refer to simply as nourishment barriers. Of course, there is the inevitable decline and ultimately death of all organisms; however, even death can be seen as an extremely important part of the process of life.

Based upon this framework, then, supporting an organism in either maintaining their health or in returning to optimal health after having lost it, consists really of only two things: (1) supporting the organism in continuing to meet the needs that are getting adequately met, and (2) identifying what needs are not being adequately met, if any, and supporting the organism in developing more effective strategies for meeting them. This will most likely include attempting to identify any nourishment barrier(s). Before looking more closely at these, it will help to first outline what I actually mean by “needs,” and then what I mean by “nourishment barriers.”

A Hierarchy of Needs

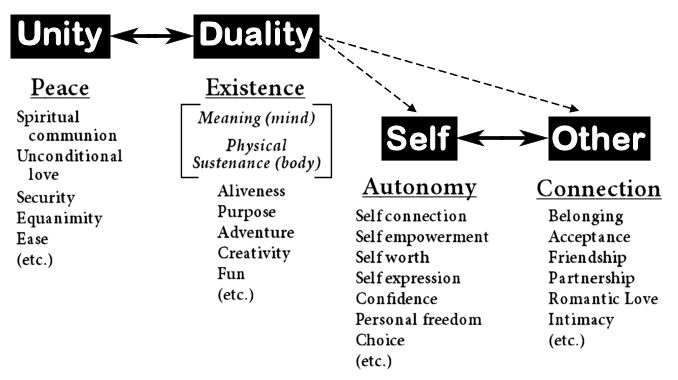

Based upon deep inquiry into subjective experience (as discussed in the first part of this article), we can say that there exists a hierarchy of needs, with those needs most fundamental to basic existence coming first. These include the basic requirements of the body—air, healthy food, water, adequate temperature/shelter, an adequate balance of rest and fitness—and the basic requirements with regard to the organismic process as a whole—both enough peace and enough meaning so that the organism’s natural desire to maintain one’s existence will continue. These most fundamental of the needs are then followed by the basic needs within the self/other dialectic (autonomy and connection with others), which is then followed by a wide array of needs that can generally be categorized beneath each of these more fundamental categories (see Figure 1 for this basic structure of needs as it pertains to the human organism). It’s important to acknowledge that these overarching categories (existence/peace and autonomy/connection) are dialectics rather than dichotomies, so we find an interesting dynamic typical of dialectics in that having needs met on “one side” generally supports rather than hinders those on the “other side” being met, while none of these can ever be perfectly satisfied (e.g., existence will never entail perfect peace, and perfect autonomy cannot coexist with perfect connection with others).

Figure 1. The most fundamental levels of our hierarchy of needs.

Nourishment Barriers

Considering the idea that optimal health is simply an innate quality of all organisms whose needs are adequately met, and that all organisms continuously strive to meet their needs, we can assume that when needs are not being met, there must be something that is acting as a kind of nourishment barrier. This barrier could be the simple lack of availability of a particular resource (such as the lack of water for a person who spent a little too much time in the desert, or the lack of affectionate love for a stray kitten). Or it could be that a particular resource is available, but that something has happened to the organism itself which has resulted in its inability to take in and be nourished by the resource.

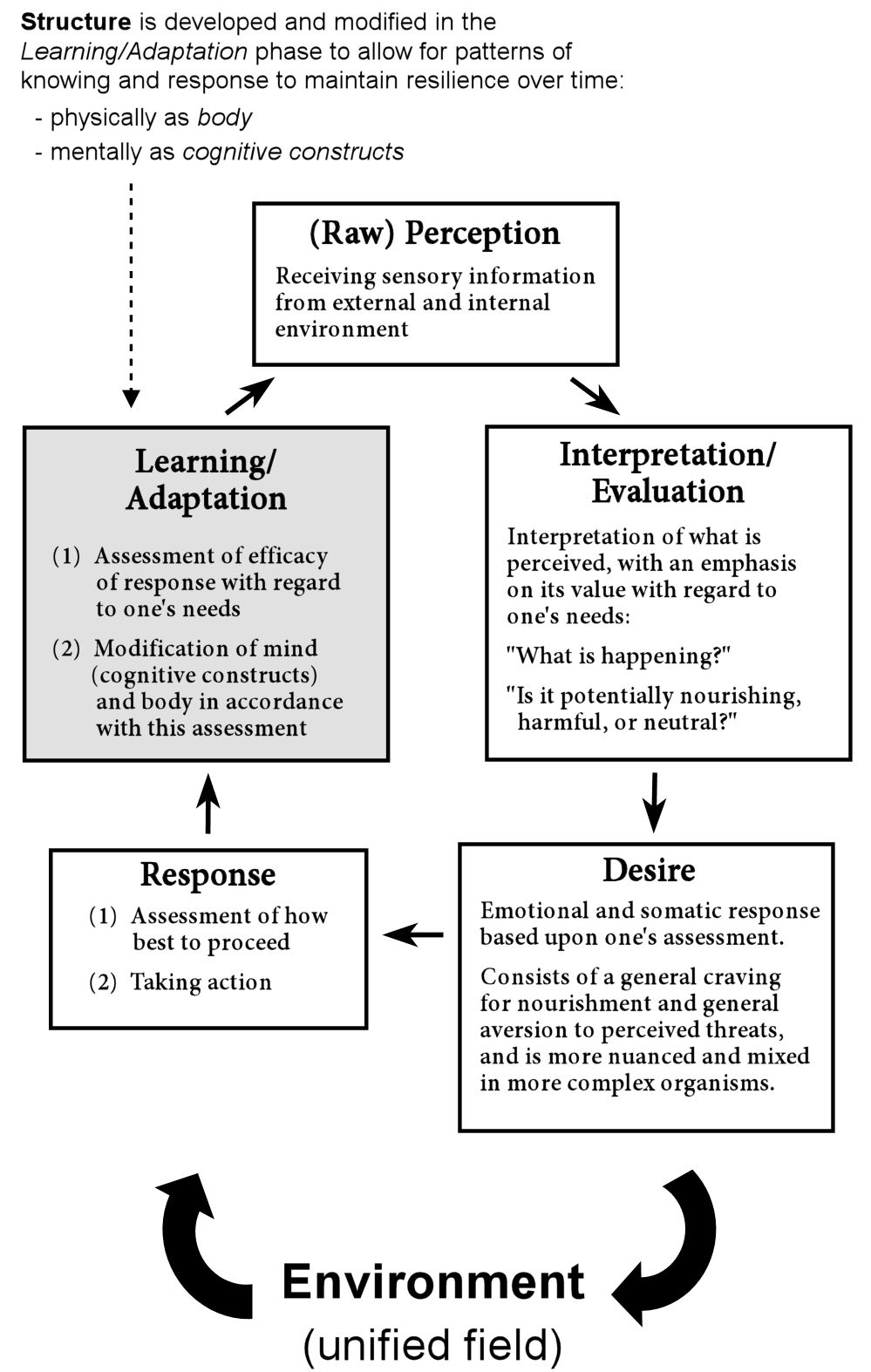

Recall that an organism consists essentially of an organismic process from which emerges structure, both in the form of the subjective cognitive constructs and in the closely related physical structure (see Figure 2). The basic organismic process itself is essentially invulnerable—it’s innate within the very fabric of living beings and continues to function as long as there is life. However, the structures that provide enhanced capacity and specific guidance (the cognitive constructs and the body) can develop significant problems which reduce the various capacities within the organismic process. So when assessing for barriers to nourishment, it’s often helpful to try to determine which of these two aspects of the structure of the organism is most directly associated with it, although we need to acknowledge that this distinction is not always so clear given the very close relationship between these two. It may also be helpful to consider which phase of the organismic process—perception, interpretation/evaluation, desire, response, and learning/adaptation—is most directly affected by the nourishment barrier.

Figure 2. The organismic process

Although the topic of nourishment barriers that are most directly associated with bodily structure generally falls outside the area of my own expertise, I’ll give a few examples here of some of the more obvious such barriers that can occur. A damaged eye or ear will likely reduce the capacity for perception—the process of perception itself will still occur as long as there is life (being a fundamental component of the organismic process), but such damage will likely lead to a significant reduction in the organism’s capacity in this regard. The loss of a limb will clearly reduce the organism’s capacity for both perception (somatic perception in this case) and response. Damage to the central nervous system, ingestion of a psychoactive substance, or invasion by a harmful parasite can all lead to reduced capacities with regard to any and every phase within the organismic process, depending upon the particular damage done. And the list of other such possibilities is virtually limitless.

Turning to the idea of nourishment barriers that are most closely associated with the cognitive constructs, we enter the territory of what are generally known as mental disorders (also often referred to as “mental illnesses”)—those kinds of distressing subjective experiences that the DSM and other similar systems have tried so hard to categorize. The paradigm presented here offers us a way to recognize that there really do exist more or less common patterns of distress and limitation (i.e., nourishment barriers) that are most closely associated with one’s cognitive constructs without having to (a) try to reduce them to some pathological disease process occurring within the body, or (b) disregard the organismic wisdom (the continuous drive towards health and the meeting of one’s needs) that underlies these barriers.

Regarding the assumption that problems occurring within the mind must imply some physiological disease process, it’s important to acknowledge that this assumption comes straight from the debunked positivistic worldview, with its belief that everything can be reduced to matter (i.e., the body; see the first part of this article for more discussion about this). Of course, as has been discussed, for anything that occurs within the mind, there will certainly be directly corresponding changes occurring within the body—after all, body and mind are merely two different perspectives of the same process. And the more extreme a particular experience or change is with regard to one, the more extreme an experience or change we would expect to find within the other. Indeed, we have identified significant and lasting changes occurring within the body as the direct result of emotionally traumatic experiences and other kinds of extreme subjective experiences. However, this does not imply that a disease process is occurring. Quite to the contrary, I believe it’s more appropriate to view these kinds of changes as simply being the physical manifestation of the organism’s attempt to adapt to these challenging experiences in the best way that it can. Even with this wisdom/health-oriented perspective, however, it’s important to recognize that once particular patterns are set up to deal with difficult situations, these can often result in lasting limitations (nourishment barriers) if and when the situation improves. In other words, a distressed organism is often put in the situation of having to sacrifice its capacity with regard to meeting one kind of need in order to reinforce its capacity with regard to meeting another. One example of this is the development of a suntan, which reduces the harm caused by UV radiation at the cost of a diminished capacity to synthesize Vitamin D via sunlight; another example is the development of a greater capacity to shield oneself from the pain of emotional rejection at the expense of reduced capacity for experiencing more satisfying intimacy with others.

Let’s turn now to look at the most common kinds of nourishment barriers that can result from issues within one’s cognitive constructs, and the phases of the organismic process that these are most likely to affect:

Problems with perception

Arguably, one’s cognitive constructs rarely have any direct effect on our raw perception of the world (the key word here being “raw,” also sometimes referred to as “bottom up processing”). Any problems that arise here are most likely to be associated with bodily structure—some physical problem occurring within the organs of perception themselves or the neural networks associated with them. An important exception to this rule is that one’s cognitive constructs do guide an organism with regard to what it is the organism chooses to pay attention to. I believe, however, that any nourishment barriers associated with attention are more appropriately considered to be problems with either interpretation/evaluation or response, as discussed below.

Problems with interpretation/evaluation

The interpretation/evaluation phase is guided greatly by one’s cognitive constructs, so many and perhaps most of the symptoms considered to be associated with so called mental disorders are likely to be associated with issues occurring within this phase.

Limiting core beliefs: These are beliefs that have developed which interfere with meeting certain needs. We can assume that such beliefs aren’t just formed out of thin air—after all, the cognitive constructs and the beliefs and interpretations contained within them are fundamentally in the service of meeting the organism’s needs. However, due to experiencing certain kinds of difficulties in life, it is very common to come to believe that certain needs must be sacrificed in order to meet other needs (e.g., sacrificing intimacy for safety or autonomy, authenticity for belonging, meaning for ease, etc.). While these assessments may be more or less accurate initially, if they remain in place after the situation has changed and whatever resources were scarce are now more abundant, then a problematic nourishment barrier can result.

Affective disorders (including the so called anxiety disorders and so called mood disorders): These are generally the result of assessing certain emotions themselves as being dangerous in some way, which in turn results in a combination of heightened vigilance and aversion towards these emotions, which in turn increases their intensity and leads to a painful positive feedback loop and an entrenched condition of feeling overwhelmed by the very same emotions one is trying so hard to avoid. Since emotions are actually just messengers letting us know how we’re doing with regard to meeting our needs, this is akin to “shooting the messenger.” It can be seen essentially as a strategy to achieve short-term ease but at the expense of increased long-term suffering.

Somatoform and pain disorders: These are similar to the affective disorders in that they are generally the result of assessing sensations which occur naturally within the body (often interoceptive sensations, which are closely associated with emotions) as representing a disease or other serious problem. This generally results in significant aversion towards these sensations, which ironically increases one’s vigilance towards them and actually results in them being felt even more intensely, leading to a painful positive feedback loop and eventually a serious difficulty with meeting one’s needs for peace and ease.

Addictions and impulsivity: Generally speaking, these are probably also similar to the affective disorders in that particular emotions or other inner experiences are assessed as being particularly harmful, which in turn leads to the propensity towards behaviors that elicit powerful pleasant feelings or even just simple relief (such as certain psychoactive substances, extreme sports, eating excessive amounts of “junk food,” risky sexual behaviors, etc.). In other words, particular emotions or other inner experiences are experienced as so painful or harmful that the person resorts to behaviors that offer short term relief at the expense of longer term harm. The use of psychiatric drugs would also generally fall into this category. Obsessive-compulsive type behaviors also generally fit in here in that the compulsive behavior (e.g., repeatedly washing one’s hands, intensive “checking,” etc.) typically provides short term relief from the unpleasant affect triggered by the particular “obsession” (concern about germs, concern about causing harm, etc.), but at the expense of increased long-term distress as their lives become increasingly constricted.

Other kinds of intrapsychic conflict: These include other kinds of distressing or limiting patterns of thought or behavior similar to the affective, somatoform and impulse disorders mentioned above, in that the person is identifying some aspect of their inner experience (emotions, sensations, thoughts, images, impulses, etc.) as being harmful in some way, and so gets caught up in a kind of wrestling match with her/his own inner experience. This can lead to all kinds of painful intrapsychic conflicts and distressing patterns of thinking and/or behavior.

Trauma: Trauma is generally believed to be the result of mistaking a particular threat (typically that which initially caused the trauma) as continuing to exist in spite of significant evidence to the contrary, which suggests that this would generally be considered an issue most closely related to this phase. Some researchers, however, have come to the conclusion that a more accurate way of perceiving trauma is to see it as a kind of aborted response—the well established fight-flight-freeze response remaining “stuck” somehow in the freeze mode—which suggests that trauma, or at least certain kinds of trauma, may be more appropriately considered an issue with the response phase, or perhaps a more complex issue that spans across both of these phases.

Anomalous beliefs (so called delusions): These refer to the development of belief systems that are not in accord with the general belief system held by the larger social group to which the person belongs (i.e., consensus reality). From the constructivistic and needs-based paradigm presented here, what’s of utmost importance is exploring whether these beliefs are interfering with the meeting of one’s needs, rather than trying to determine if the beliefs are “true” in any kind of absolute sense. Many anomalous beliefs actually are not particularly limiting; however, the very fact that they are nonconsensus indicates that they may make it more difficult to meet needs associated with belonging and acceptance from others who are more identified with the mainstream culture.

Anomalous perceptions (so called hallucinations): These refer to perceptions within any of the five somatic sensory modalities that are not in accord with the general perceptions of other members of one’s larger social group (i.e., consensus reality). It can be helpful to recognize that these are often the result of mistaking events occurring within one realm of perception (e.g., imagination, memory, the collective unconscious, etc.) as occurring within another (vision, hearing, somatic sensation, etc.). Again, when offering support, it’s not trying to determine whether or not they are objectively “true” that is likely to be most helpful, but determining whether or not they interfere with the meeting of one’s needs.

Psychotic disorders: Finally, we have disorders consisting of distressing anomalous perceptions and/or beliefs, which are usually combined with one or more of the other types of nourishment barriers in this and other phases of the organismic process. These conditions are generally given labels such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, mood disorders with psychotic features, schizoaffective disorder, etc., an act that probably causes much more harm than benefit. Such labeling suggests that all such conditions have a common underlying issue and therefore benefit from a common “treatment” (typically antipsychotic or mood stabilizing drugs). This is an idea that has not even come close to being substantiated—in fact, quite the contrary, especially in the light of the framework presented here, which suggests significant heterogeneity among many of these different conditions. Another problem with such labeling is that it often suggests a problem when there is none. For example, there are many people who have anomalous perceptions or beliefs without any significant nourishment barriers being associated with them. Having said this, however, it does appear that there may be one particular pattern of experience that may be seen to have a common underlying issue—that which we often think of as a more “florid” kind of psychosis. See Problems with learning/adaptation below for more about this.

Problems with desire

Arguably, we never really have a problem with desire itself (recall that desire in this context includes the broad categories of craving and aversion, and the wide array of emotions that these give rise to). Emotions are, after all, just the messengers. They are simply the generated desire or impulse to respond in a manner appropriate to the assessment that was made in the previous phase. So when we develop the so called affective disorders, we are essentially making the mistake of trying to shoot the messenger, which is why I feel these are more appropriately deemed a problem with assessment rather than being a problem with the process of desire itself (see discussion of these above).

Problems with response

Response (also commonly referred to as behavior) actually involves two parts: determining the best response to meet one’s needs within the context of the current situation, followed by the response itself. So one’s cognitive constructs play just as important a role here as they do in the interpretation/evaluation phase. Clearly, many problems can result in this phase considering that this is the phase where direct action takes place, and of course all actions have consequences, which is the point of acting, after all. I suspect, however, that the vast majority of problematic responses are simply the natural result of problems occurring within the interpretation/evaluation phase (as discussed above), and so would be more appropriately considered as nourishment barriers within that phase.

Addictions and impulsivity: As mentioned above, most likely the majority of addictive and impulsive behaviors are more appropriately considered issues with interpretation/evaluation. However, another reason such behaviors may occur, perhaps especially those sometimes labeled “ADHD,” is that the person doesn’t spend enough time considering the most effective response strategy before moving into action, and therefore often acts in ways that are not ideal for meeting one’s needs. This could be the result of a number of different factors, including a fixation on instant gratification of one’s needs at the expense of long term nourishment, a simple mismatch between the general temperament of the individual and those who she/he regularly interacts, or experiencing a chronic hyperarousal as the result of trauma or generally feeling unsafe in some way.

“Thought disorders”: It turns out that many and perhaps most of the experiences referred to as “thought disorder” are actually not the result of a person having their thoughts literally disordered (although this can be the case—see other kinds of intrapsychic conflicts above). This term refers to a “symptom” that is sometimes assigned to people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, specifically referring to the act of speaking in ways that others find difficult to understand. Research suggests that in most cases, these would be more accurately considered a communication disorder, since the actual problem being pointed to is ineffective communication. In this case, we could consider this a response issue (the inability or unwillingness to respond effectively to the situation), but only if the person’s speech is actually interfering with the person meeting their needs. R. D. Laing and others have pointed out some interesting cases in which the person actually did appear to be meeting certain needs with this kind of behavior.

“Catatonic” or bizarre behavior: These are generally described as being either “bizarre” behavior or the lack of behavior altogether. The first consideration is that the “problem” may be primarily with the observer, in that she/he simply doesn’t understand what is going on for the person exhibiting this behavior, and so assesses it as a “problem.” Some people have reported, for example, that they utilized behavior that seemed “bizarre” to others (such as pacing or rocking oneself for long periods of time) as a way to provide some relief from overwhelming affect; so this would actually be considered an effective response to meet their needs given their situation, and not a nourishment barrier. There are individuals, however, who have reported experiencing significant distress during times in which they felt they either couldn’t stop moving in a particular way or they couldn’t move at all. People sometimes describe this kind of experience as occurring when they feel trapped in a particularly intense state of ambivalence (feeling intensely pulled to act in contradictory ways), which would indicate a kind of nourishment barrier that could either be seen as primarily associated with response or interpretation/evaluation (or some combination of the two), depending upon the specific details.

Problems with learning/adaptation

Rigid vs. Flexible Cognitive Constructs: Learning, or adaptation, is where an organism intentionally changes its own structure—both the mental structure (one’s cognitive constructs) and the associated physical structure— in an attempt to maximize efficiency with regard to meeting its needs in the face of an ever changing environment and an ever changing self. On the mental level, this manifests as changes within one’s cognitive constructs, and on the bodily level, this manifests as the modification of any relevant part of the body, including muscle tissue, bone density, skin pigmentation, neural networks, the components of the immune system, etc. With regard to changes made to the cognitive constructs, we can say that there is a more or less optimal degree of flexibility. If they’re too rigid, the ability to learn and adapt to changing circumstances is diminished. If they’re too flexible, achieving any kind of sustainable balance or order becomes difficult, and the potential to slip into a chaotic process (i.e., psychosis) becomes more likely.

Florid psychosis: It’s generally the condition of highly flexible cognitive constructs and the ensuing chaos that results in the kinds of conditions we often think of as psychotic disorders, especially the more florid varieties—one’s cognitive constructs become highly unstable and can change relatively quickly and radically. It appears that this can occur for a number of reasons, including as the result of certain powerful psychoactive drugs or other powerful mind altering experiences, and even as a process initiated intentionally by the organism when a particular configuration of one’s cognitive constructs has resulted in an intolerable and/or unsustainable way of being (an idea that emerged in my own doctoral research, and was presented in my book, Rethinking Madness—you can also find a brief summary of these ideas here). This process, then, could be seen as the organism’s attempt to reorganize one’s cognitive constructs at a very deep level, risky and precarious as that may be. Since the cognitive constructs play a particularly important role in guiding the organismic process, when they fall into such a chaotic state, it’s easy to see why the entire organismic process is so profoundly affected, and why so many of the different nourishment barriers that have been listed above can appear. Recalling that within living systems we have come to recognize chaos as being a particularly important condition in allowing for the emergence of new orders, it actually makes a lot of sense that an organism would intentionally initiate such a chaotic state as part of a desperate attempt to achieve a more sustainable order.

Part Two:

Supporting the Natural Health Process

So, after outlining the basic needs and many of the possible types of nourishment barriers that can appear, the final and of course most important part of this model is exploring the implications for supporting an organism’s health. While this same basic model can presumably apply to all living organisms and living systems, I’ll narrow down the scope of this exploration for now to the health of the human being.

What I feel is the single most important implication of this framework is recognizing that all organisms contain an innate drive towards optimal health as well as the profound wisdom to facilitate this process. This manifests as simply the ability to recognize one’s needs and the desire and capacity to work towards meeting them. So the process of attempting to restore health that has been compromised generally entails working out what is interfering with the meeting of one’s needs (the nourishment barriers) and resolving them. Fortunately, in spite of the many different patterns of nourishment barriers outlined above (and perhaps others I haven’t identified here), it appears that there is really only one kind of nourishment barrier—that of limiting core beliefs—deeply held understandings that interfere with the ability to meet one’s needs in the most efficient manner given the situation at hand. However, I think it can be helpful to break this up into two overarching categories—intrapsychic conflicts, which are those limiting core beliefs that consist of the direct assessment of one’s own inner experience as harmful, and other kinds of limiting core beliefs:

Intrapsychic Conflict—evaluating one’s own inner experiences (emotions, thoughts, impulses, images, memories, sensations, etc.) as being harmful, and therefore engaging in a kind of intrapersonal tug-of-war. I often like to refer to this kind of dynamic as “shooting the messenger.” Most of these inner experiences can be seen as being merely messages regarding which needs are or are not being met. Whereas it is certainly important to try to determine the accuracy or usefulness of any particular message, it is generally much more beneficial to cultivate a willingness to be open to whatever arises within one’s experience than to get involved in these kinds of intrapsychic wrestling matches. By resorting to strategies that try to suppress or directly alter these experiences, we risk missing out on valuable information, and we risk wasting our energy on a more or less futile internal struggle when this energy would probably be better spent developing more effective and sustainable methods for meeting the unmet needs that these inner experiences are likely pointing to. In their more extreme forms, these kinds of intrapsychic conflicts can manifest in ways often considered psychotic (e.g., struggling with anomalous perceptions such as voices or visions, becoming deeply engrossed with inner experience at the expense of not being able or willing to engage with others externally, etc.)

Other kinds of limiting core beliefs—in addition to those limiting core beliefs involving the direct struggle against one’s own natural inner experience, other limiting core beliefs can develop which typically involve either the evaluation that some needs must be sacrificed in order to meet others and/or the evaluation that certain needs simply cannot be met at all. I believe this is often the result of mistaking what are actually dialectics (both/and situations) for dichotomies (either/or situations)—for example, believing that we have to choose between having either autonomy or love from others, rather than recognizing that a healthy relationship consists of both of these. These kinds of limiting core beliefs may very well originate as accurate assessments of a particularly difficult situation; however, they represent a real nourishment barrier when they remain somewhat entrenched after the situation has improved. In their more extreme forms, these kinds of limiting beliefs can manifest in ways we think of as psychotic (e.g., so called paranoia, messianic striving, etc.).

I suspect, then, that virtually all of the nourishment barriers (at least those considered primarily mental in that they’re most directly associated with one’s cognitive constructs) could be seen as arising from either direct intrapsychic conflict, other limiting core beliefs, or some combination of the two; and a psychotic process, in which one’s cognitive constructs shift into a relatively chaotic state, simply creates the conditions in which someone becomes particularly vulnerable to relatively intense versions of both of these.

Effective Methods of Support

So moving on to explore the most effective methods of supporting oneself and others in moving towards optimal health, it will help if we consider that there are only a relatively small handful of core needs that essentially gives rise to all of our other needs—these being peace, meaning, autonomy/self connection, and connection with others; see Figure 1 above), and that there are essentially only the two types of nourishment barriers mentioned above (intrapsychic conflict and other limiting core beliefs). Therefore, we can deduce that the best methods for supporting health are those that address these most fundamental needs and any associated nourishment barriers.

Healthy Relationships

When we look to most of the major schools of psychotherapy and other kinds of psychosocial support, we find that, generally speaking, they are already naturally trying to target the various nourishment barriers outlined above, although they each tend to emphasize different phases (without necessarily describing them as such), and of course the practitioners of each generally believe that their own methods are the most effective. When research studies have been conducted comparing the outcomes of the different approaches, however, a very interesting finding emerges—it appears that the single most important factor determining therapeutic outcomes is not any particular method or technique, but the quality of the client/therapist relationship itself. And when questioned about the particular qualities of the relationship that clients find most helpful, they generally report these as including the sense that the therapist really cares about them and genuinely wants to understand them while also supporting their authenticity and choice. In other words, we’re really talking about the principles that Carl Rogers, one of the founders of humanistic psychology, emphasized decades ago—genuineness, positive regard and empathy. So what is it about a relationship with these particular qualities that is so helpful?

This kind of relationship essentially creates a safe container where a person can connect more fully with their own experience and also with another human being, feeling encouraged to do so in a relatively open and curious way. One important aspect of this kind of work is that the attitude of openness and curiosity towards one’s inner experience that is cultivated here naturally works towards dissolving any intrapsychic conflicts. Another important aspect of this is that the therapist acts as a kind of safe and caring “reflecting board” where feelings and needs are brought to the forefront, and any limiting core beliefs naturally rise to the surface where they can be explored and reevaluated. A third important aspect of this situation is that the person is able to experience a healthy relationship with another human being, where one’s autonomy is valued at the same time that intimacy is allowed to deepen safely.

In other words, within such a relationship, we have a situation in which the most fundamental needs are generally being met (self connection and autonomy, connection with another, meaning and peace), and the main types of nourishment barriers (intrapsychic conflict and other limiting core beliefs) are being naturally addressed and worked through. The real beauty of this kind of relationship is that it does not need to be limited to a professional therapist, but actually represents nothing more nor less than that which occurs naturally within a healthy human relationship. I think it’s actually a real tragedy that we live in a society that generally values material wealth over the fostering of such relationships, and we have a mental health care system where the head honchos (typically the psychiatrists) are trained much more extensively in the use of drugs than in cultivating this kind of healthy interpersonal connection. Even psychologists often receive far more training in particular psychotherapeutic “interventions” than they do in developing the ability to cultivate this kind of relationship with their clients. We have already seen a natural movement in our society towards sanctuaries and family support systems designed to foster this kind of support for people in real need. If we want to live in a thriving and healthy society, then putting our resources into encouraging and expanding this movement is clearly in the best interest of all of us.

Self Connection

Even when such a healthy interpersonal relationship is not immediately available, we all have the capacity to practice powerful self connection. Recall that emotions are not our enemies, no matter how unpleasant they may be—they are simply the messengers, letting us know how things are going with regard to meeting our needs. Unpleasant emotions typically are associated with needs that are not being met, and pleasant emotions are typically associated with those that are. As discussed above, if we perceive our emotions as something “bad” or “wrong,” and get involved in a wrestling match with them, trying to change them or push them away, then we will likely get tangled up in painful intrapsychic conflicts. However, if we recognize our emotions for what they are, we can open up to them and try to hear their message—what needs are getting met, and what needs are not? So, developing this level of self connection—which we could also call self empathy or connecting with one’s aliveness—not only puts us into direct contact with the information we need to achieve optimal health, but it also dissolves intrapsychic conflict and likely brings awareness to other limiting core beliefs.

Mindfulness

As discussed earlier, mindfulness is a practice developed several thousand years ago in India that consists of simply cultivating the ability to be present and accepting with regard to one’s inner experience. One benefit, as already discussed, is the potential to develop an awareness of one’s own subjective experience at a very deep level. However, the cultivation of the ability to be at peace with one’s subjective experience is just as important as the cultivation of awareness. So this kind of practice clearly offers the potential to address both of the main types of nourishment barriers—dissolving intrapsychic conflict and resolving other limiting core beliefs.

By developing this combination of such powerful self connection along with increased tolerance of difficult feelings and experiences, mindfulness practice allows us a way to strengthen our ability to perceive our situation more clearly and also to contemplate more effective responses. In other words, considering that most of what we generally call mental disorders are ultimately associated with either problematic assessment of one’s situation and/or problems in responding in effective ways, mindfulness practice offers way to directly resolve a lot of these problems by increasing one’s capacity to both meet one’s needs in a satisfying manner and to resist the impulse to respond in potentially impulsive and harmful ways during those times when one’s needs are not being satisfyingly met. It’s like offering someone the possibility of going to the gym to strengthen one’s organismic capacity as a whole, rather than merely strengthening a particular muscle. So in this way, mindfulness practice clearly has the potential to greatly promote health. Although these benefits have been well known in parts of Asia for millennia, the field of Western psychology has finally appreciated this very powerful method, and consequently, it is being incorporated into many of the mainstream Western psychotherapeutic approaches.

Cultivating Meaning

As has been discussed, peace and meaning are among the most essential needs that we have, and according to this framework, these two are actually very closely related in that they essentially make up the two poles of the peace/existence dialectic. In order to better understand this, it will help if we first explore the issue of meaning. In order to want to continue to exist, it is very clear that we need to connect to some kind of personally meaningful activity or direction in which to channel our life energy. While the methods mentioned above can certainly aid in this regard, they’re often not enough. According to the framework presented here, the peace/existence dialectic lies at the very heart of our experience (see Figure 1 above), and being a dialectic, it’s helpful to recognize that a workable resolution consists of developing a strategy or a way of being in the world that transcends both poles.

Recall that the existence pole consists of both a mind and a body aspect (meaning and physical sustenance) and the peace pole consists of experiencing that which transcends our dualistic existence altogether—what is often experienced as an aspiration for spiritual communion or simply the connection with something that transcends the limited self. So with this framework in mind, we can recognize that in order to cultivate a life that contains both “good enough” meaning and “good enough” peace, we need to find a way to channel our life energy in a direction or towards a cause that both includes and transcends our personal sense of self. This could be as simple as raising or supporting a family, or it could involve devoting oneself to a particular cause, ethical principle, or spiritual practice or tradition. Existential thinker Ernest Becker sometimes referred to these practices as “immortality projects” in that they fend off the deeply held terror of our own mortality. I believe that this perspective has some merit; however, I feel that it’s placing too much emphasis on just one side of this dialectic. I believe that any truly meaningful aspiration not only staves off the fear of our own mortality, but also connects us to the awe, wonder and beauty that are naturally evoked when we reach beyond the bounds of our limited self and grasp the much greater dance of life of which we are all a part.

Healthy Body, Healthy Mind, Healthy World

Maintaining a healthy body is of course also essential for full organismic health. Recall that body is essentially the material structure that emerges from the organismic process and allows certain patterns of knowing and response to remain relatively resilient over time. And mind is simply the subjective experience of this entire process—what it all feels like from the inside. Given this understanding, it’s simply common sense that if the body does not receive adequate nourishment (physical sustenance) or is injured or damaged in some way, then the entire organism including one’s subjective experience will likely be adversely affected. Fortunately, such physical sustenance is not particularly difficult or complicated, since organisms by their very nature strive to gain maximum benefit from whatever resources are available. Generally speaking, such sustenance consists of regular nutritional food, water, shelter, exercise, and protection from other invasive or potentially harmful organisms (such as parasites and predators); and if these basic bodily needs are not adequately met, then a whole host of problems can arise that ultimately act as various kinds of nourishment barriers within the organismic process.

This framework also provides an interesting perspective for understanding those problems we often refer to as “physiological diseases.” While this topic takes us into areas in which I don’t personally have a lot of expertise, I do find some of the implications that arise from this framework interesting. Recall that any particular organism is actually part of a much broader hierarchical arrangement of organisms—from the single cell, to an organ or organ system, to the entire multicellular organism itself, to the ecosystem to which these belong, and finally to the entire biosphere. The health of each of these is ultimately dependent upon the health of the other orders of organismic organization on either side of it on this ladder of organizational complexity. For example, in the case of a human being, if a single cell develops the particularly limiting core belief in which it “forgets” that it is a member of a larger organism, it may resort to fixating on its own individual survival and develop into a cancerous growth that ultimately kills the entire organism. Similarly, if the immune system of a complex organism develops a limiting core belief in which it determines that some part of the larger organism is harmful, an autoimmune disorder may develop. And to give one final and particularly poignant example, if the human organism develops a similar limiting core belief and “forgets” that it is merely one member of the broader ecosystems and the Earth’s biosphere in general, then this organism may act very much like a cancerous cell, focusing on its own individual survival while wreaking great havoc on the higher-ordered organisms upon which it is so dependent (the ecosystems and even the entire biosphere).

So, by considering that this same organismic process is occurring on each different organismic level, we may find it easier to work towards a more holistic system of health that’s more supportive not only of individual organisms but of the entire web of life to which all organisms belong. A controversial topic closely related to this idea is that of selfishness vs. altruism. Within the context presented here, there really is no such thing as altruism, at least not in the sense of intentionally acting in a manner that is beneficial for others. Rather, we recognize that as the illusion of distinct boundaries between “self” and “other” fades, and we experience our sense of “self” expanding to encompass other organisms and ultimately the entire web of life, our “selfishness” also naturally fades. As we identify with this more expanded sense of “self,” we naturally want to act in ways that are of the greatest benefit to “others,” especially those “others” who we begin to incorporate into our own sense of self. To put this in another way, we could say that it is innate for all organisms to act “selfishly,” but that the way this manifests is determined by the organism’s experience of what “self” actually is.

Implications for Mainstream Medical Model “Treatment”

In stark contrast to the methods of support mentioned above, so called medical model “treatment” operates from the unsubstantiated premise that all so called mental disorders are caused by some disease process occurring with the body (and typically the brain in particular). Those who subscribe to this way of thinking often pay lip service to the importance of psychosocial factors, but usually only in the sense that these may make it more or less difficult for a person to cope with their disease. So as would be expected with this kind of framework, the primary treatments of choice consist of physiologically-based interventions, which nearly always include psychiatric drugs and encouraging/coercing people into having “insight into their illness” so that they’ll take them. Let’s take a moment to look at the implications of this kind of treatment based on the framework presented here.

When we convince someone that they have some kind of disease process occurring within their brain which in turn gives rise to certain subjective experiences (such as emotions like sadness, anger, or anxiety, or certain kinds of thoughts, beliefs, perceptions, images, memories, impulses, etc.), what do you think is likely to occur? Intrapsychic conflict, of course. The person’s own fear and general aversion towards these inner experiences are likely to increase, they become more likely to enter into tug-of-war relationships with their own inner experiences or increase the strength of those already existing, and are therefore likely to become more deeply entrenched in what would otherwise most likely be relatively transient experiences. Periods of grief or sadness intensify into chronic “depression,” the natural ebb and flow of anxiety intensifies into full fledged “anxiety disorders,” transient psychoses or other anomalous experiences harden into lifelong “psychotic disorders,” etc. And not only is this kind of distressing inner turmoil more likely to occur as a result of such treatment, but because the person is actually encouraged by “professionals” to go ahead and “shoot the messenger,” the person is now much more likely to miss out on valuable information regarding the unmet needs that most likely lie at the root of whatever the actual problem was in the first place.

So what about the drugs? Well, generally speaking, drugs can be seen as a particularly powerful method of “shooting the messenger,” whether they be psychiatric drugs or illicit drugs. In the absence of drugs, people who want to avoid unpleasant emotions or other unpleasant inner experiences generally find themselves having to resort to relatively mundane strategies of distraction or repression. But these are like mere bee-bee guns when compared to the heavy artillery of psychoactive drugs. Anytime we develop strategies which allow us to avoid feeling our own emotions (or other kinds of inner experience), we are essentially buying short term relief at the expense of the kind of authentic self connection that is generally required to address our needs in a more sustainable manner. And just as we would expect based upon the holistic organismic framework being presented here, we find a particularly robust and consistent pattern resulting from psychoactive drug use—short term relief (sometimes) at the expense of significant long term harm (usually). While I believe that this kind of strategy may have some usefulness, especially as a form of crisis intervention when the person feels completely overwhelmed by their inner experiences, it’s important to acknowledge the very steep price that comes with this strategy in the form of reduced self connection, the reduced capacity to tolerate unpleasant experiences, and whatever other side effects may be caused by the particular drug.

While on the topic of drugs, it’s interesting to consider the implications that this framework provides for why placebos work the way that they do. Placebos are strikingly effective for many (perhaps most) of the conditions that are listed here as nourishment barriers, in spite of their being completely inert physiologically. When someone receives a placebo, the person typically believes that they may be receiving some kind of support for whatever condition it is with which they’re struggling. If we consider that most of these conditions (especially those we’re calling primarily mental) arise from intrapsychic conflict (i.e., assessing one’s emotions and other inner experiences as being harmful in some way), then the placebo response makes perfect sense. Something is taking care of the offending emotion or other inner experience, so it’s finally okay to let down one’s guard. In other words, the placebo often results in the person revising their assessment of the perceived harmful experience as being not so harmful anymore, which in turn allows them to let go of their intrapsychic struggle, which in turn is likely to reduce or even eliminate the very thing that was causing so much unnecessary distress in the first place. So just as the “disease model” understanding of mental disorders acts as a nocebo in that it promotes increased intrapsychic conflict, a placebo provides the means to ease this conflict.

So, Wrapping It All Up into a Nutshell . . .

. . . life consists of an often mysterious blend of mind and body, order and chaos, joy and suffering, and autonomy and symbiosis taking place within a profoundly dynamic, interdependent, and interconnected relational field. The very essence of all living organisms consists of a powerful drive towards health and wholeness, and the great wisdom to carry this out. Optimal health is an organism’s most natural state, and anything short of this suggests that certain needs are simply not being adequately met. The obvious implication of this is that the most effective means of supporting an organism’s health includes supporting it in identifying its unmet needs and in removing any associated nourishment barriers. This includes especially addressing any barriers to its natural ability to accurately perceive, evaluate, respond to and learn from its environment. Any system of support or other kind of system that delivers inaccurate information, doesn’t honor the organism’s own understanding, limits the organism’s freedom to respond in a natural manner, and limits its freedom to learn and grow in a natural manner, is a system that interferes with health, healing and growth.

If we seek to move in the direction of a genuinely healthy and sustainable world, and if we take the time to reflect upon how well our society’s institutions of health, education, safety, peace and order are doing with regard to the principles mentioned above, then it becomes painfully clear just how much work we have to do. It is definitely time to put on the work gloves.

*My ultimate plan with this thesis is to expand it into a book that is much more thoroughly referenced than the bare-bones version of it here. In the meantime, if you’re interested in my sources for a lot of these ideas and information, feel free to contact me for specific references or further reading with regard to any of the specific topics presented here. Also, I really hope you will let me know your thoughts on these ideas. Thanks!

Good stuff here Paris. Thanks for this two-part posting.

David

Report comment

Thanks, David. That means a lot to me to hear that you’re enjoying my work.

Paris

Report comment

Wow! It’s all so true. What I particularly like about what you’ve written is (1) You’ve made the same observations and have the same understanding that I do, biology and wholistic related, butwith better charts and clearer explanations. Sometimes even when among members of the movement, it has not been easy to communicate where I am coming from, so reading your post is a treat (2) You go into a comprehensive discussion of what works and why which also explains why the current pervasive paradigm does not heal or help. It just makes so much darned good sense.

Report comment

Wow! It’s all so true. What I particularly like about what you’ve written is (1) You’ve made the same observations and have the same understanding that I do, biology and wholistic related, but with better charts and clearer explanations. Sometimes even when among members of the movement, it has not been easy to communicate where I am coming from, so reading your post is a treat (2) You go into a comprehensive discussion of what works and why which also explains why the current pervasive paradigm does not heal or help. It just makes so much darned good sense.

Report comment

Thanks, metalrabbit. I’m really glad to hear you resonate with these ideas.

What you say makes a lot of sense, in that I really just see these ideas as a return to a much more common-sense way of understanding the joys and challenges of being alive. I don’t see my work as really introducing anything particularly new, other than just trying to integrate the many bits of wisdom coming from a lot of different traditions–trying to fit the pieces together to create a broader coherent picture–and putting it all into a humanistic framework that hopefully resonates with people’s actual lived experiences. My ultimate goal is to collaborate with other like-minded folks such as yourself to come up with a useful model that can replace the horribly dysfunction system that is currently in place.

Paris

Report comment

Paris, I haven’t yet read through much of what you wrote (these posts are long), but what small part I read it resonates pretty much with my own home-baken system I’ve grown over the years. For instance, I’ve been pretty interested in neuroscience and especially kind of a computational neuroscience where you try to learn the algorithms of neural networks. I’ve also been interested in mind and its relation to brain and body and environment and society and etc. I’ve practiced martial arts based on taoist stuff and also a little chi kung+kungfu. Also a little yoga. Right now I try to practice zazen (zen meditation, a form of mindfulness practice) daily and connect it with western science and also widen it to my daily life. This with hikes in nature and finding the right nutrition, and working about how new habits are created and old ones lost, and willpower .. maybe willpower can be seen as a habit/s .. and connecting all of these as kind of a mosaic .. wow.

Report comment

Thanks for sharing some of your own journey towards deeper understanding and health. It does sounds like you and I have taken a similar tack of drawing from widely disparate perspectives and experiences in an attempt to fill out a fuller picture and enjoy a broader experience of all of this existence stuff. I ditto your “wow”–it’s quite a ride, eh? 🙂

Paris

Report comment

I am replying to your comment on my first comment, having read your part two. You are definitely inching towards a much better way of seeing basic human psychology – which is that we use ones resources as best one can to get our essential needs met. And if we fail for whatever reason, be it because the environment is bad or as a misuse of our resources, then mental distress (not illness) will arise. And so on this paradigm, individuals and societies can be judged as healthy or not. I imagine you would agree with this restatement of what you have said.

I am speaking as a humble Human Givens practitioner and not in any sense one of the founders or leading lights of Human Givens. So I can say this I hope without causing offence. You are in danger of attempting to reinvent the wheel. Much of where you are has been done and much more besides. I urge you to investigate much more about HG. And a good place to start would be by reading the second edition of the Human givens book – here http://www.humangivens.com/publications/human-givens-book.html

There is a great synthesis out there – but work from what already exists.

Report comment

Thanks for sharing all this. The Human Givens approach looks great

It’s important to remember that I am working from what already exists, something that I readily acknowledge–we are all piggybacking off of the pioneers of humanistic psychology and the human potential movement, and then going further back, from paradigms far, far older than these such as those associated with the nondual traditions of the East and what was probably more or less ubiquitous within the indigenous cultures (the roots of all other paradigms that have emerged since, though somehow we have fallen very far from these roots in many ways, and a few tendrils are just now beginning to make their way back).

You’ve got me curious about the Human Givens work–I’ll check out that book you mentioned.

Thanks again,

Paris

Report comment

yes we stand on the shoulders of giants but for us to really buy into a model or way of seeing and processing something, we have to experience it and not just read it on a page. And certainly HG is inspired by the ancients, notably Sufism.

best wishes and enjoy the book.

Andrew

Report comment

Paris, thanks very much for writing your 2 part piece on rethinking mental health. It is truly a gift to come across your piece today as so much of it resonates strongly with me. I very much look forward to more from you on this topic. I note that these comments are from 2013 so I am curious as to whether you have progressed toward writing your book on this topic? In any case I will keep an eye out for further writing from you. I am both a consumer and a provider of support services and I have found much here today to help meet my needs in both areas. Thank you!

Report comment

Hi Oceanfire1 (cool name btw),

I’m glad to hear that you find my work so helpful and that it resonates with your own experience.

Since writing this piece, I have continued to contemplate these ideas deeply, to dialogue with others about them, and to test them in the “real” world–in the work I do with my clients and in my own life. And this has all led to feeling ever more confident that this perspective has real merit, with really no significant modification to these ideas since I’ve written this piece.

I’m now contemplating how to expand these ideas into a book that is easily comprehensible to people, regardless of their education, and which is grounded in real life stories and experiences. I also want to include a section that is more politically-oriented–looking at how the current political system is resulting in profound “external nourishment barriers,” (i.e., the simple lack of available resources necessary for everyone’s wellbeing)–rather than have the book be focused exclusively on “internal nourishment barriers,” as is the case with this piece here.bI haven’t fully embarked on this stage of the project yet, though I plan to within the next few months. I’ll keep the MIA community informed on my progress.

Thanks for your interest and your support!

Paris

Report comment

Hi Paris,

My name is Bryan. My username oceanfire1 was inspired by Rumi poetry.

I found your approach of taking “the issues all the way down to the most fundamental assumptions and experiences that give rise to them, and then try to reconstruct an understanding that is more conducive to meeting our needs” as particularly helpful.

I especially found useful your unpacking of the basic assumptions underlying the most prevalent scientific paradigm in the West, that of positivism, and the reasons you believe this paradigm is so problematic. I too believe this predominant scientific paradigm is problematic and have felt anger about the harm it has been causing but up until reading your piece I lacked a name for, and a deeper understanding of the basic assumptions underlying, the paradigm of positivism. I intend to research this area further to deepen my understanding.

I wholeheartedly agree that this perspective has real merit. I’ve experienced the benefits of a more holistic, interdependent vision and the practices that naturally flow from such a vision in my own life and in the lives of those I have worked with.

I greatly look forward to your expansion of these ideas into a book which is easily comprehensible and grounded in real life experiences and stories – that will not be an easy task but the challenge will be well worth the effort and will be immensely valuable to both practitioners and the general public. I especially like that you plan to include a section on how the current political system is resulting in profound “external nourishment barriers”. I believe this is key as another problematic result of positivism as I understand it is the situating/locating of ‘pathology” within the person which ultimately harms and disempowers the person while discounting or outright dismissing the existence of “external nourishment barriers”.

Good luck with this project, I look forward to updates here at MIA as your work progresses.

Cheers,

Bryan

Report comment

Paris – Hi, you don’t know what you are saying in that sign-off. Here are my thoughts…

I thought you were offering condensation/s from Rethinking Madness. Since your ambitions are correlative to the discussion and intentional being (not to mention Being &/v. Becoming), you ought to casually read through Joseph Margolis’s Historied Thought, Constructed World: A Conceptual Primer for the Turn of the Millenium. You need a week or two, but it’s a casual first helping rounded out for support of his conception of the I- vs. the i- intentional. For an easy good day’s read, there’s Auberry Castell’s The Self in Philosophy, which determines self as activity. But I’d take Professor Hacker’s final say on the matter in his fairly recent Human Nature, for which, to see what you’ve got coming you might skip over to Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. It’s something to do, deciding this terminological point. The review by a feisty, miffed German academe will reveal what irritates about the work that is not its weakness, its limitation, or its furthest reach, and certainly not any parochial results. Joseph Margolis also has a plausible discussion of the defensible possibility of reincarnation in his Philosphical Problems (or Problem in Philosophy or something), but your first priority ought not to be there with him: it takes a few periods of adjustment between chapters for his arguments’ development to stick right with the case in point of whichever you’re on–not saying you couldn’t just look ahead for the R. But it hasn’t an index. If you haven’t read it already, or have already gotten to the other types of thing to your satisfaction, Thomas Szasz’s The Meaning of Mind certainly becomes fond to remember, as he sidesteps much needless philosphizing himself. Now that I have gotten acquainted with Hannah Pickard’s manner and position, I should probably read that one again. Her “Mental Illness Is Indeed A Myth” appears in Matthew Broome’s and Lisa Bortolotti’s (eds.) whatever that I haven’t read–Psychiatry as Cognitive Science: Philosphical Perspectives. She must have a hate-following, as she’s honest, kind, and in the business. Her chapter, which is online, gives the lowdown on Boorse and Szasz in short order, and doesn’t stop short of neutrality regarding the respective authors’ fates.

I liked in this piece of yours how the discussion recognizes that the labels put out there don’t in themselves give anyone very much to work with. The imagination put into the vast and more than the vast bulk of the literature could fit in two places fast, a dustjacket or the test pattern. I take issue with you can’t/won’t displacement regarding worst cases. It’s still won’t if it’s not neurological by definition, if the problem resides in conceptual constructs for all parties in question. They’ve had enough time for something a-normative. Maybe you mean the nurse’s can’t “How are we?” kindly, witty, freewheeling, appropriate, perhaps untrained. Or maybe you’ve gone at it with the i/Intentional and I don’t see the Can’t yet.

Interestingly, where you are wrapping up core beliefs, I felt like you only left yourself the final explanation for the curious, most remarkable and inquisitive survivor, that they had done it all to themselves, unintentionally, gotten out of whack. Not very pricey or elegant, but common in a good way, safe enough (I hope). For the purpose of enlisting colleagues, your style earns points, since the debate is up on the approach to opening a space for sharing. You do it now. You keep with it and keep doing it now. I would, however, put in a word for Murray Bowen over and above Carl Rogers for emphasis on tenacity. Rogers didn’t oppose much, that I’m aware of, and insisting that psychologists shouldn’t just never misbehave and call it quits took a lot of podium time. Mabye I don’t know his big confrontation with silent “P”, the malfeasant to death. Bowen is also the thinking man’s Heinz Kohut. Years ago, I read an issue of some academic journal devoted to psychological interventions on reservation lands, and attachment theory was very fittingly applied and demonstrated. The multi-disciplinary explanation could not have gotten all the marrow out of it, already. Also, you obviously are ready to take on the Inner Critic supposedly universal in your field. That should be good. I never forget brain deficits and brain dysfunction, and your emphasis adequately circumnavigates the topic of what persons are that selves might not be: i. e., non-linguistic creatures. Likewise, you aim to manage your play of terms in light of disctinctions between normative judgments and the logical understanding of natural facts. Lastly, you might want to italicize the phrase in potentially harmful or dysfunctional ways, just so it stands out to refer to. This country U. S. A. is more full of pussies and liars than it ever has been, thanks in large part to the allied mental health professions, present company excepted. And they’re bad liars, man.

Report comment

Paris – So sorry good guy. I hope you recognize the sign of character defects when malapropism swing suddenly into view. Mt appending those remarks as formulated was certainly inappropriate. But let me fix it up. Engaging with your work had good effect on me, unanticipatedly good–although I have to keep working along lines that exist with established ties to the venerable Western philosophical tradition, to achieve various purposes of my own. I hate having to qualify myself, though. Also, let me explain how the offbeat humor means something about what represents a truth for me, too.

It’s like this, I can feel now that accepting what happened to me in terms of the brain deficits and dysfunction that were real results, is increasing my flow of feeling, letting me sort out some less articulable emotional reactions, too. This, without proof to the effect, I attribute to sustained attention to the reality of the whole likelihood in direct and immediate relation to your discourse on the same, mostly in the first half. And it was all free, right? Sure. Maybe you know about the problem supposed here, with psychological and psychiatric conditions, causally linking re-expereincing to dysfunction of VAM. Well, who knows….

But anyway, I sort of can feel when things are getting different, and it is the appearance often enough of the well known feeling of waiting for what has happened too much already. Many variations on this a-functional syndrome continue to plague me. So, to stay on track for you, as your schedule requires, but thanks to this free comment thread, the thing that strikes me immediately upon excepting everything that has happened to me, as much as I can tell, getting over lots of intrapsychic conflict is that I don’t like my predicament now and can’t move ahead as I’d like to grow rapidly into acceptance of the situation and future life experience it suggests. So it burns me up, that all the years I sought help, the professionals, in one way or another were afraid of everything that was not the paradigm in place, and it just held me up at every turn. So I do think that it is important to see potentially abnormal or dangerous or bad and thoughtless misbehavior as lurking behind every distressing, tumultous emotion or uncertain idea of what they mean. I really do think it is the Left’s malfeasnce that dominates the goals of these profession–witness the pornablum of advertisement for psych hospital over what you can get done out free, recently in PT. The legal manipulations and social control measures just are what inevitably gets supported by the rule of specious fear of lost reputability or taking the wrong side (the patient’s) in a conflict with the big guys in his life, by at least an order of magnitude and automatically in numerous times and ways.

Anyway, I finally decided–hastily, but I’m still willing, to see somebody for EDMR if she will return my call. Again, it bothers me to comply at all, to see what should not be considered more than natural fact given normative significance without my say. Such is the place.

Report comment