As the schizophrenia/psychosis recovery research continues to emerge, we discover increasing evidence that psychosis is not caused by a disease of the brain, but perhaps may best be described as a last ditch strategy of a desperate psyche to transcend an intolerable situation or dilemma. To better understand how this understanding which is so contrary to the widespread understanding of psychosis has emerged, it will help if we break this discussion into two parts: (1) a summary of the research associated with the “brain disease theory” of schizophrenia/psychosis; and (2) a summary of the research that has given rise to this alternative understanding.

Part One: Taking a Closer Look at the Brain Disease Theory

In spite of over a hundred years of research and many billions of dollars spent, we still have no clear evidence that schizophrenia and other related psychotic disorders are the result of a diseased brain. Considering the famous PET scan and MRI scan images of “schizophrenic” brains and the regular press releases of the latest discoveries of one particular abnormal brain feature or another, this statement is likely to come as a surprise to some, and disregarded as absurdity by others. And yet, anyone who takes a close look at the actual research will simply not be able to honestly say otherwise. And not only does the brain disease theory remain unsubstantiated, it has been directly countered by very robust findings within the recovery research, it has demonstrated itself to be particularly harmful to those so diagnosed (often leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy), and it is highly profitable to the pharmaceutical and psychiatric industries (which likely plays a major role in why it has remained so deeply entrenched in society for so many years, in spite of our inability to validate it).

Deconstructing the Myths of Madness

The claim I am making here clearly runs counter to the mainstream understanding of schizophrenia, but we find that it’s a relatively straightforward task to back up this claim. We simply need to take the time to extract the actual research findings from the unsubstantiated assumptions and propaganda that are so often used to back up the brain disease theory. I’ll go through the most prevalent of these here:

Hypothesis #1: Schizophrenia is caused by a biochemical imbalance within the brain

This theory originated from the observation that drugs which block the transmission of the neurotransmitter dopamine within the brain (so called “antipsychotics,” originally referred to as “major tranquilizers”) appear to reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia. The reasoning behind the origin of this hypothesis was, since schizophrenic symptoms are reduced when dopamine transmission is suppressed, then perhaps schizophrenia is caused by excessive dopamine within the brain.

This hypothesis originally appeared quite plausible; however, it has since been seriously discredited:

First, although it is known that an individual’s dopamine receptors (the type of receptors most affected by antipsychotic drugs) are completely blocked within hours of consuming a sufficient dose of an antipsychotic drug, the actual antipsychotic effects often do not become apparent for up to several weeks (although a significant degree of apathy towards one’s psychotic experiences often does kick in quickly, as would be expected with any kind of tranquilizer; Bentall, 2004). If psychotic symptoms are the direct result of too much dopamine, then why don’t we see a more immediate abatement of these symptoms as soon as the dopamine levels have been effectively reduced?

Second, with the introduction of PET and MRI scans, the dopamine hypothesis was apparently substantiated when it was recognized that many “schizophrenic” brains do indeed seem to be set up to transmit excessive dopamine. However, it was eventually realized that the vast majority of brains studied had been exposed to long-term antipsychotic drugs, and it’s since been established that the effects of these drugs alone may very well account for these anomalies (Burt, Creese, & Snyder, 1977; Kornhuber et al., 1989; Mackay, 1982).

Finally, even many of the proponents of this theory have been forced to acknowledge that we still have not found any clear biochemical imbalance that we can associate consistently with schizophrenia or any of the “mental illness” diagnoses, and that all we can really say for sure is that psychiatric drugs themselves do lead to the development of a biochemical imbalance in one’s brain (Hyman & Nestler, 1996; Whitaker, 2002).

Hypothesis #2: Schizophrenia is caused by anomalous brain structures

This hypothesis essentially states that schizophrenia is a disease caused by something wrong with the actual structure of one’s brain, specifically with regard to the relative size of the cerebral cortex and/or other nearby regions of the brain. This hypothesis is generally supported by the actual findings of such anomalies of the brains of those so diagnosed. But again, upon closer inspection of the research, we find an empty hypothesis that quickly crumbles away:

First, we have discovered that there are many different factors that can lead to these abnormalities, including: depression, alcoholism, early childhood trauma (Read, 2004), water retention, pregnancy (Woodruff & Lewis, 1996), advancing age, variations in educational achievement, social class, ethnicity, and head size (Bentall, 2004). It was also discovered that the sizes of these regions of the brain can fluctuate quite rapidly within even healthy individuals, leading to varying results even within the same individual (Bentall, 2004). And once again, what do you imagine we have found that is probably the most relevant factor causing such anomalies in the brain? You guessed it… the use of antipsychotic drugs themselves. And virtually all of the research that has discovered such brain anomalies in those diagnosed with schizophrenia did not account for this very important factor, meaning that once again, most of the brains studied had most likely been adversely affected by the long-term use of antipsychotic drugs (Read, 2004; Siebert, 1999).

A second serious challenge to the validity of the abnormal brain structure hypothesis came when it was recognized that the majority of those diagnosed with schizophrenia do not show any obvious brain abnormality at all. Lewine found that “there is no brain abnormality in schizophrenia that characterizes more than 20-33% of any given sample. The brains of the majority of individuals with schizophrenia are normal as far as researchers can tell at present [emphasis added]” (Lewine, 1998, p. 499); and this in spite of the fact that most of these participants were likely exposed to other brain changing factors such as trauma and/or antipsychotic medications. Conversely, it is common to find healthy individuals who have no schizophrenic symptoms at all and yet have brain abnormalities similar to those sometimes found in schizophrenics (Siebert, 1999).

Hypothesis #3: Schizophrenia is a Genetic Disorder

This hypothesis is in close alignment with the two brain disease hypotheses mentioned above and suggests that this brain disease is transmitted genetically. But again we find some serious problems with the assumptions that have given rise to this hypothesis:

This hypothesis is based on a small handful of twin and adoption studies (Joseph, 2004) conducted many decades ago which, even when we ignore the many serious methodological flaws with these studies, the only conclusion that can actually be drawn from them is that there may be a hereditary component in one’s susceptibility to developing psychosis. However, this is not any different than the findings that there may be a hereditary component in intelligence, shyness, and other psychological characteristics that clearly are not indicative of any kind of physiological disease.

In other words, it’s an illogical leap to assume that a hereditary predisposition for a psychological trait or experience must imply biological disease. Yes, there does seem to be some evidence that some of us may be born with a temperament or other psychological characteristics which make us more vulnerable to experiencing psychosis at some point in our life; but no, this evidence does not lend any validity to the hypothesis that schizophrenia is a genetically transmitted biological disease.

Another important area of research discrediting the “genetic disease” hypothesis is the far more substantial research showing high correlations with environmental (non-hereditary) factors and the development of psychosis/schizophrenia. For example, One study looked at 524 child guidance clinic attendees over 30 years and discovered that 35% of those later diagnosed with schizophrenia had been removed from their homes due to neglect, a percentage twice as high as that for any other diagnostic category (Robins, 1974); another study found that 46% of women hospitalized for psychosis had been victims of incest (Beck & van der Kolk, 1987); another study of child inpatients found that 77% of those who had been sexually abused were diagnosed psychotic compared to only 10% of those who had not been so abused (Livingston, 1987); and yet another study found that 83% of men and women who were diagnosed with schizophrenia had suffered significant childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, and/or emotional neglect (Honig, Romme, Ensink, Escher, Pennings, & de Vries, 1998). Bertram Karon, researcher and acclaimed psychosis psychotherapist, has found evidence of a high correlation between the experience of intense feelings of loneliness and terror within childhood and the later onset of schizophrenia, a finding that is clearly closely related to the findings of these other studies (Karon, 2003).

Even the strongest proponents of the brain disease hypothesis acknowledge that it has not yet been validated

The National Institute of Mental Health, on its Schizophrenia home page, proclaims confidently that “schizophrenia is a chronic, severe, and disabling brain disorder” (NIMH, 2010a, Para. 1), a statement you find on nearly every major page or publication they have put out on the topic; and yet if you spend a little more time looking through their literature, you will find that they admit that “the causes of schizophrenia are still unknown” (NIMH, 2010b, Para. 1). Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association also confidently proclaims that “schizophrenia is a chronic brain disorder” (APA, 2010, Para. 1), but then they acknowledge on the very same page that “scientists do not yet know which factors produce the illness” (APA, 2010, Para. 10), and that “the origin of schizophrenia has not been identified” (APA, 2010, Para. 1). The strong bias towards the brain disease theory is clearly evident in the literature of these and other similar organizations, and yet the message comes through loud and clear that we still do not know the cause of schizophrenia. Even the U.S. Surgeon General began his report on the etiology of schizophrenia with the words, “The cause of schizophrenia has not yet been determined” (Satcher, 1999, Para. 1). It would appear, then, that it is simply not appropriate to claim with such confidence that schizophrenia is the result of a brain disease.

If schizophrenia really is a brain disease, then how do we account for the relatively high rates of full recovery from it?

One finding within the recovery research that is extremely robust is that many people experience full and lasting recovery after having been diagnosed with schizophrenia. We see this evidence in the vast majority of the longitudinal recovery studies (See Chapter 4 in my book, Rethinking Madness, for a complete list of all major longitudinal studies), including those conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health (Harrow & Jobe, 2007; Harrow, Jobe, & Faull, 2012) and the World Health Organization (Hopper et al., 2007). There is evidence of spontaneous recovery in between 5% and 71% of cases, depending upon the country of origin and other factors, and even as high as 82% with certain psychosocial interventions (Mosher, 1999; Seikkula, Aaltonen, Alakare, Haarakangas, Keränen & Lehtinen, 2006). It is illuminating to compare the high recovery rate for schizophrenia with the recovery rate for well-established diseases of the brain such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Hungtington’s, or Multiple Sclerosis, in which there is no well documented evidence of even a single individual making a full recovery from any of these (Siebert, 1999). Furthermore, we see evidence that many of those who have experienced full recoveries from schizophrenia and other related psychotic disorders do not just return to their pre-psychotic condition, but experience profound healing and positive growth beyond the condition that existed prior to their psychosis, again in stark contrast to the well established diseases of the brain (Williams, 2011, 2012).

The mainstream paradigm of care may actually be creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of brain disease

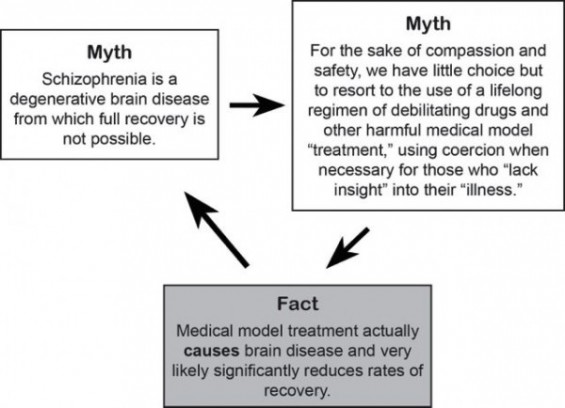

While we continue to have no solid evidence that schizophrenia/psychosis is the manifestation of a diseased brain, we do discover one particularly tragic irony in that our very entrenched belief in this theory and the paradigm of care that has resulted from it is actually ensuring that enormous numbers of people actually do develop brain disease (see Figure 1).

.

Figure 1. A vicious circle caused by the brain disease theory of schizophrenia

Isn’t it time, then, that we finally let go of the brain disease theory?

In summary, then, we find that in spite of well over a hundred years of research and billions of dollars spent, the brain disease theory remains entirely unsubstantiated; and that our persistent yet unfounded faith in this theory may very well be generally causing much more harm than benefit (or at least causing significant harm to those so diagnosed at the cost of great financial benefit to certain key players within the current mental health care establishment).

Part Two: Towards an Alternative Understanding of Schizophrenia/Psychosis

So, if schizophrenia/psychosis is not caused by a disease of the brain, then what does cause it? This is not a simple question, and it’s further complicated by the fact that there continues to be widespread controversy over whether or not the concept of “schizophrenia” as it is currently used is even a valid construct, an issue that needs to be addressed first before suggesting an alternative model for understanding schizophrenia and the other related psychotic disorders.

Moving from discrete “mental illnesses” to a continuum of experience

The debate about the validity of the concept of “schizophrenia” arises from recent research suggesting that (1) all of the various major psychotic disorders may simply be variations of one phenomenon, and (2) there may be not be distinct boundaries between psychosis itself and what we think of as sanity. The British Psychological Society (the BPS, Great Britain’s counterpart to the American Psychological Association), in its official report summarizing their understanding of “mental illness” and “psychotic experiences,” concluded that the various psychotic disorders may more appropriately be classified as variations of one phenomenon, a phenomenon that many have suggested we refer to simply as psychosis or madness.

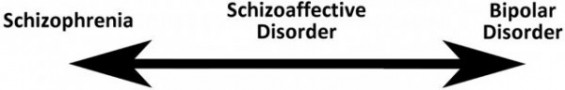

Taking this conclusion one step further, the BPS suggested that “mental health and ‘mental illness’ . . . shade into each other and are not separate categories” (2000, p. 17). In other words, they suggest that not only are the various psychotic disorders best understood as merely representing different points along a continuum of a single phenomenon (see Figure 2), but that sanity and madness themselves are also best understood as being merely different points along a single continuum (see Figure 3). They cite evidence suggesting that psychotic experiences are merely extreme expressions of more ordinary traits found within the general population.

Figure 2. Seeing the major psychotic disorders as lying on a common continuum.

When psychotic experiences contain primarily cognitive features (so called delusions and hallucinations), a person is most likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia; when affective instability predominates, a person is most likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder; and when a person experiences a significant combination of both of these, they are most likely to be diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

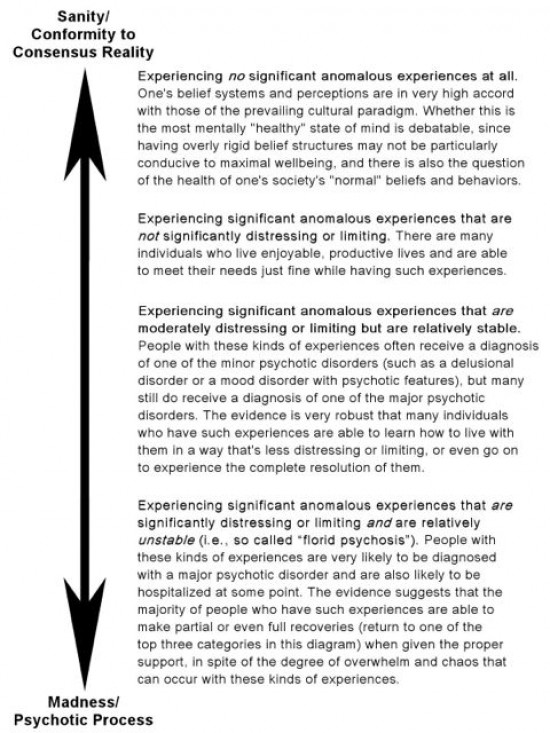

Based upon the findings of my own research and my review of the other relevant research, I’ve come to the conclusion that it can be helpful to see the “sanity/madness” continuum as being defined by essentially two factors: (1) the degree of resonance or dissonance of one’s experiences with consensus reality (where consensus reality is defined as the understanding of reality that is generally agreed upon as being the most legitimate within a given individuals’ society); and (2) for those having experiences that differ significantly from consensus reality (let’s call them anomalous experiences), the degree of distress, limitation, and/or instability that is associated with these experiences. With these two factors in mind, then, we can divide the sanity/madness continuum into four separate categories of experience, keeping in mind that these don’t represent discrete categories but merely act as place markers along a common continuum of experience; see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The “Sanity/Madness Continuum.”

By considering anomalous experiences from a continuum perspective, we arrive at some very different implications regarding how to best define such experiences and what is the best way to support those who experience them:

First, we recognize that the line between so called “sanity” and so called “madness” is somewhat arbitrary—that it’s not helpful and probably not possible to pinpoint any discrete “illnesses” along this continuum.

Second, we recognize that the problems associated with anomalous experiences are probably not due so much to the fact that they deviate from consensus reality, but rather are more likely due to the difficult relationship an individual may have with these experiences (e.g., distress caused by hearing persecutory voices or holding persecutory beliefs, along with unusual or even harmful behavior that may arise in someone’s attempts to deal with them). One implication of this is that it’s important to distinguish between those anomalous experiences that cause distress or limitation, and those that don’t. If they’re not causing any problems, then what’s the problem? Why call it psychosis? Considering these kinds of experiences to be “psychotic” or giving them a name such as “schizophrenia” or “delusional disorder” appears to be unhelpful and likely even harmful, especially if such individuals are inculcated into the unfounded belief that these are the manifestations of a diseased brain.

A second important implication of this idea is that, when these kinds of experiences do cause distress or limitation, it’s likely that the best support we can offer does not consist of trying to bring the individual’s experience back into alignment with consensus reality, but instead consists of helping them meet their needs from within the context of their own experiences. The literature is filled with research and biographical accounts supporting this idea (for example, Chadwick, Birchwood, & Trower, 1999; Romme et al, 2009).

Finally, as an individual’s experience does move further down the continuum into the realm represented by the two categories listed at the bottom of Figure 3, evidence from my own research (Williams, 2011, 2012) as well as that of other recovery research (e.g., Arieti, 1978; House, 2001; Karon & VandenBos, 1996; Laing, 1967; May, 1977; Mindell, 2008; Nixon et al, 2009, 2010; Perry, 1999) suggests that they may be entering a powerful psychological process entailing the transformation of their self and their personal paradigm at a very profound level (more on this shortly). This is the process that often gets equated with “florid psychosis” and is typically the hallmark condition that so often gets labeled as “schizophrenia” or as one of the other major psychotic disorders.

Since the term “schizophrenia” is so heavily laden with unfounded assumptions, as we’ve been discussing, I’ll simply refer to this process as “the psychotic process” or “psychosis” in order to maintain some congruence with the terminology already used within the field (while acknowledging that the term “psychosis” also comes heavily laden with problematic assumptions). After all, we can say that the condition that so often gets labeled as “schizophrenia” (or one of the other major psychotic disorders, depending upon the specific nature of the anomalous experiences) is essentially just long term psychosis.

So, what causes psychosis?

Returning, then, to the question of what causes psychosis, I’ll preface my discussion of this question hereby saying that I’ve devoted an entire book (Rethinking Madness—Williams, 2012) to a thorough exploration of this question, so unfortunately, it’s just not possible to adequately summarize and back up a thorough answer to this question within such a brief article. What I will attempt to do here, however, is to put forth the most essential concepts of this alternative understanding and hopefully encourage others to engage in fruitful discussion about this important topic.

While I don’t believe it’s a stretch to say that our attempt to validate the brain disease theory of these disorders has so far been a colossal failure, there is a very different line of research that I believe has had much more success in providing significant clues as to the cause of these vexing disorders. The line of research I’m referring to is the research that has inquired directly into the actual lived experiences of those who have personally experienced psychosis.My own recent research is particularly relevant in this regard, which includes a series of three studies inquiring deeply into the experiences of those who have experienced full and lasting recovery from long term psychosis (Williams, 2011, 2012).

I have found that the findings of this line of research have converged sharply upon a fundamental cause of these psychotic disorders that is perhaps best stated something like this: The individual we deem “schizophrenic” or “psychotic” is merely caught in a profound wrestling match with the very same core existential dilemmas with which we all must struggle. In other words, it appears likely that psychosis is not caused by a disease of the brain but is rather the manifestation of a mind deeply entangled within the fundamental dilemmas of existence.

So, what are these existential dilemmas?

The term “existential dilemma” essentially refers to the dilemmas inherent in finding ourselves in a state of existence—“Here I am, alive, conscious, and feeling. Now what?” These dilemmas, at their core, relate to our need to maintain our existence, and perhaps even more importantly, our need to create a life that is worth living—where the joys and rewards of living are strong enough to overcome the inherent pain and suffering of life and provide us with the will to go on living. Some of the most pertinent such dilemmas that have been named by various existential thinkers are: finding a balance between love/belonging and authenticity/autonomy; finding a balance between freedom and security; coming to terms with the fact that all of our decisions and actions come at some cost; coming to terms with our own impending death; and cultivating enough meaning in our lives so that we are able to rise out of bed every morning and greet each new day.

In virtually all of the research and case studies I have come across that have looked closely at the actual subjective experiences of those who have fallen into a psychotic process, we see evidence that, prior to the onset of psychosis, these individuals had found themselves in overwhelming existential dilemmas similar to those mentioned above, but to a far greater degree than that which the average person ordinarily experiences. In one of the most well-known such studies, R. D. Laing, a Scottish psychiatrist renowned for his pioneering research on schizophrenia and his clinical work with those so diagnosed, closely studied the social circumstances surrounding over 100 cases of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, and he concluded that “without exception the experience and behavior that gets labeled schizophrenic is a special strategy that a person invents in order to live in an unlivable situation [author’s emphases]” (1967, pp. 114-115).

Bertram Karon, one of the world’s most renowned clinicians specializing in psychotherapy for those diagnosed with psychotic disorders, stated his belief that any one of us would also likely experience psychosis if we were to have to live through the same set of circumstances as those of his psychotic clients (Karon & VandenBos, 1996). We see other evidence of this again and again in the plethora of biographical and autobiographical accounts that have been written and filmed (for example, Bassman, 2007; Beers, 1981; Dorman, 2003; Greenberg, 1964; Modrow, 2003).

The focus of my own research (Williams, 2011, 2012) was to explore the change that takes place with regard to one’s experience and understanding of the world and one’s self (one’s personal paradigm) throughout the entire psychotic process, from onset to full recovery. The findings that emerged with regard to the onset of psychosis were very much in alignment with the findings of the other research mentioned above—there is clear evidence that every participant in all three of my own studies had also experienced such an overwhelming dilemma prior to the onset of psychosis. After thorough analysis of the data in the final and most comprehensive of the three studies, I arrived at the conclusion that there were essentially two fundamental dilemmas that appeared to lie at the crux of both the onset and resolution of these participants’ psychotic process:

The need to achieve a sustainable balance between autonomy (personal choice/personal freedom/authenticity) and connection (love/belonging/acceptance)

The need to maintain a relatively secure and stable sense of self when the very fabric of one’s being and indeed of the entire universe is profoundly groundless, impermanent, and interconnected.

What is particularly interesting about these dilemmas is that they may be the very same dilemmas that lie at the core of all human experience, regardless of one’s degree of sanity or lack thereof. It’s likely that most of us can easily relate to the first dilemma—we only need to think of the various challenges we’ve had in our relationships with family members, partners, and other loved ones. We can also easily witness this dilemma occurring within toddlers as they struggle to find a balance between the drive to explore the world and assert their autonomy while still wanting to be unconditionally loved and accepted by their caretakers. And of course this dilemma never fully goes away for most of us.

The second dilemma mentioned above is probably a little more difficult for some of us to relate to, especially for us Westerners (many practitioners of some of the Eastern traditions such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Advaita Vedanta have thoroughly explored this dilemma). This dilemma generally lies a little more deeply beneath our conscious awareness than the first dilemma, though it often becomes conscious in unusual circumstances, such as during psychological/emotional crisis, intensive contemplative practice (such as mindfulness meditation), and hallucinogenic drug use.

So, if these existential dilemmas are universal, then why do some individuals become more overwhelmed by them than others, and go on to develop psychosis?

The research suggests that there are two main factors that may make someone vulnerable to experiencing one or both of these dilemmas to a very high degree:

With regard to being overwhelmed by the first existential dilemma (that of finding a tolerable balance between autonomy and relationship), developmental and/or acute trauma appears to play a particularly strong role. It has long been established in the field of developmental psychology that healthy childhood development requires that we find a healthy balance between our sense of autonomy and our trust that we are loved and accepted by others.

Attachment research has been exploring and validating this idea for decades. Childhood abuse (physical, sexual, and/or emotional), trauma, neglect, and a poor fit between the temperament of a child and her/his caretaker(s) all clearly interfere with establishing a healthy balance in this regard, and all of these are well established in predisposing someone to developing serious emotional and psychological problems, and in more extreme cases, psychosis (Karen, 1994; Mahler, Pine, & Bergman, 1973; Rathus, 2006; Schore, 2002; Slade, 1999; Wallin, 2007; Williams, 2011, 2012).

Recall that the second existential dilemma refers to our need to maintain the sense that we are a relatively secure and stable self living in a relatively secure and stable world, when the reality of our situation is very different than this. To better understand how someone can be overwhelmed by this dilemma, it will help to first touch on the concept of cognitive constructs. The term cognitive constructs refers to the belief systems and interpretations that each of us has constructed throughout our lives which allow us to make sense of the world.

They can act somewhat like a double edged sword for us. On one hand, they provide us with the means to distinguish one object or being from another, and they give us the general sense that we “kinda know what’s going on” so that we can meet our needs and navigate our way through life. They also give us a sense that there is some solid ground beneath our experience—in other words, that we are a secure and stable self living in a relatively secure and stable world. But on the other hand, our cognitive constructs can close our minds to other perspectives, and they create the illusion that the world and our self are much more stable and secure than they actually are.

For most of us, our cognitive constructs are fairly solid, changing only slowly over time. However, in certain cases, such as during acute crisis or trauma, or with the use of certain psychoactive drugs, one’s cognitive constructs can become highly unstable. On one hand, this can lead to the potential benefit of having a more open mind (less rigid belief systems) and the richness of experiencing a greater sense of interconnectedness with all (more about this in my book, Rethinking Madness); but on the other hand, the loosening of our cognitive constructs can also lead to the potential terror of experiencing just how precarious and ungrounded our existence and self really are, which can lead to profound shifts within our personal paradigm as we desperately attempt to find some “solid ground” to cling onto once again. Such radical personal paradigm shifting is closely associated with anomalous experiences—so called delusions and hallucinations—experiences that are generally equated with psychosis.

Why some people are more prone to the loosening of one’s cognitive constructs is still somewhat mysterious—it appears that certain drugs and psychological or physiological distress may play a significant role, and some individuals may even have some genetic or developmental predisposition for such experiences. However, even though some people may be more prone to the destabilization of their cognitive constructs, it seems likely that virtually anyone has the potential to experience this if exposed to an overwhelming dilemma, situation, or trauma. It’s all too easy to find cases of extreme neglect, abuse, torture, or other trauma that have profoundly shaken up one’s experience of one’s self and the world and led to psychosis or at least psychotic-type experiences (those within the bottom three categories of Figure 3 above).

The research suggests, then, that both of these factors play an important role in the development of psychosis—an overwhelming existential dilemma and unstable cognitive constructs. The research also suggests that these two factors are very closely related, in that the experience of such an overwhelming dilemma makes one more susceptible to experiencing unstable cognitive constructs, and vice versa. It’s also important to emphasize that it is the individual’s own subjective experience of their situation that is most relevant. Sometimes, it’s easily evident to an observer that an individual is experiencing such an overwhelming dilemma (again, think of overt trauma, abuse, torture, etc.); but at other times, the individual’s crisis is not so apparent to an onlooker, though it is often all too apparent to the individual her/himself.

So, we finally arrive at the final and perhaps most important question in this discussion: “Why would an individual’s psyche intentionally initiate psychosis?”

In other words, how can something as chaotic and as potentially harmful as psychosis act as a strategy to aid someone in transcending an otherwise irresolvable dilemma? To understand this, it helps to use as a metaphor the process of metamorphosis that takes place within the development of a butterfly. In order for a poorly resourced larva to transform into the much more highly resourced butterfly, it must first disintegrate at a very profound level, its entire physical structure becoming little more than amorphous fluid, before it can reintegrate into the fully developed and much more resourced form of a butterfly.

In a similar way, when someone enters a state of psychosis, we can say that prior to the onset of psychosis, for whatever reason, they have arrived at a way of being in the world and experiencing of the world that is no longer sustainable (i.e., is poorly resourced), and it seems that their predicament cannot be resolved using more ordinary strategies. As a desperate last-resort strategy, then, one’s own psyche may initiate a psychotic process. As the individual enters into a psychotic process, we can say that their very self, right down to the most fundamental levels of their being, undergoes a process of profound disintegration; and as we have seen in the recovery research, with the proper conditions and support, there is every possibility of their continuing on to profound reintegration and eventual reemergence as a renewed self in a significantly changed and more resourced state than that which existed prior to the psychosis.

This is why the intentional destabilization of one’s cognitive constructs may be so beneficial, although of course very risky. It is this very loosening of one’s personal paradigm—of one’s experience and understanding of one’s self and of the world—that allows an individual to undergo such a profound transformation at such a deep level of their being. When such a process resolves successfully, the potential amount of growth and/or healing that this allows is enormous; but of course, when such a process does not resolve successfully, an individual’s personal paradigm may remain unstable and chaotic indefinitely (think florid psychosis).

This idea is well supported in the recovery research in the findings that many people who make full recoveries from psychosis often experience a degree of wellbeing and ability to meet their needs that far exceeds that which existed prior to their psychosis (Arieti, 1978; House, 2001; Karon & VandenBos, 1996; Laing, 1967; May, 1977; Mindell, 2008; Mosher, 1999; Mosher & Hendrix, 2004; Nixon et al., 2009, 2010; Perry, 1999; Williams, 2011, 2012). It’s important to keep in mind, of course, that such resolution is not always successful, and that an individual may remain in a psychotic condition indefinitely. But we must also not lose sight of the very hopeful findings from the recovery research that suggest that such a successful resolution from a psychotic process is surprisingly common, and may even be the most common outcome given the proper conditions and support (Hopper et al., 2007; Perry, 1999; Mosher, 1999; Mosher & Hendrix, 2004; Seikkula et al., 2006).

Finally, one particularly compelling implication of these findings is that if it turns out to be true that those who have experienced psychosis have struggled profoundly with the universal existential dilemmas that most of us have only barely consciously grasped, then these individuals may have the potential to contribute greatly to the very important human quest to understand what it is that really drives us.

Dr. Paris Williams, author of Rethinking Madness, works as a psychologist in the San Francisco Bay Area. He offers the rare perspective of someone who has experienced psychosis from both sides—as a researcher and psychologist, and as someone who has himself fully recovered after struggling with psychotic experiences. He can be reached at: www.RethinkingMadness.com/contact.

You can find a much more thorough discussion of these and related topics in Dr. Williams’ recently published book, “Rethinking Madness” (Sky’s Edge Publishing), which is available through Amazon.com and most other major retail outlets. More information is available at www.RethinkingMadness.com

References

American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2010). Schizophrenia. Retrieved from The American Psychiatric Association Healthy Minds, Healthy Lives website: http://www.healthyminds.org/Main-Topic/Schizophrenia.aspx

Arieti, S. (1978). On schizophrenia, phobias, depression, psychotherapy, and the farther shores of psychiatry. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

Bassman, R. (2007). A fight to be: A psychologist’s experience from both sides of the locked door. New York, NY: Tantamount Press.

Beck, J., and van der Kolk, B. (1987). Reports of childhood incest and current behavior of chronically hospitalized psychotic women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 789-794.

Beers, C. W. (1981). A mind that found itself. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

British Psychological Society [BPS]. (2000). Recent advances in understanding mental illness and psychotic experiences. A report by The British Psychological Society Division of Clinical Psychology. Leicester, UK: Author.

Chadwick, P., Birchwood, M. J. & Trower, P. (1999). Cognitive therapy for delusions, voices and paranoia (Wiley series in clinical psychology). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Dorman, D. (2003). Dante’s cure. New York, NY: Other Press.

Greenberg, J. (1964). I never promised you a rose garden. Chicago: Signet.

Hagen, B. F., Nixon, G., & Peters, T. (2010). The greater of two evils? How people with transformative psychotic experiences view psychotropic medications. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry: An International Journal of Critical Inquiry, 12(1), 44-59.

Harrow, M., & Jobe, T. (2007). Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: A 15-year multifollow-up study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(5), 406-414. Retrieved from http://www.madinamerica.com/madinamerica.com/Schizophrenia_files/OutcomeFactors.pdf

Harrow, M., Jobe, T. H., & Faull, R. N. (2012). Do all schizophrenia patients need antipsychotic treatment continuously throughout their lifetime? A 20-year longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine, First View Articles, 1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000220

Honig, A., Romme, M., Ensink, B., Escher, S., Pennings, M., & de Vries, M. (1998). Auditory hallucinations: A comparison between patients and nonpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 646-651.

Hopper, K., Harrison, G., Janca, A., & Sartorius, N. (2007). Recovery from schizophrenia: An international perspective: A report from the WHO Collaborative Project, The International Study of schizophrenia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press

House, R. (2001). Psychopathology, psychosis and the kundalini: Postmodern perspectives on unusual subjective experience. In I. Clarke (Ed.), Psychosis and spirituality: Exploring the new frontier (pp. 75-89). London: Whurr Publishers.

Hyman, S., & Nestler, E. (1996). Initiation and adaptation: A paradigm for understanding psychotropic drug action. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(2), 151-162. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8561194

Joseph, J. (2004). Schizophrenia and heredity: Why the emperor has no genes. In J. Read, L. R. Mosher, & R. P. Bentall (Eds.), Models of madness: Psychological, social and biological approaches to schizophrenia (pp. 67-83). New York, NY: Routledge.

Karen, R. K. (1994). Becoming attached: First relationships and how they shape our capacity to love. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Karon, B. P. (2003). The tragedy of schizophrenia without psychotherapy. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 31(1), 89-119. doi:10.1521/jaap.31.1.89.21931

Karon, B. P., & VandenBos, G. (1996). Psychotherapy of schizophrenia: The treatment of choice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, Inc.

Laing, R.D. (1967). The politics of experience. New York: Pantheon Books.

Lewine, R. (1998). Epilogue. In M. F. Lenzenweger & R. H. Dworkin (Eds.), Origin and development of schizophrenia (pp. 493-503). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Livingston, R. (1987). Sexually and physically abused children. The Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26: 413-415.

Mahler, M. S., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1973). The psychological birth of the human infant, New York: Basic Books.

May, R. (1977). The meaning of anxiety. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Mindell. A. (2008). City shadows: Psychological interventions in psychiatry. New York, NY: Routledge.

Modrow, J. (2003). How to become a schizophrenic: The case against biological psychiatry. Lincoln, NE: Writers Club Press.

Mosher, L. R. (1999). Soteria and other alternatives to acute psychiatric hospitalization: A personal and professional review. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 142-149.

Mosher. L. R., & Hendrix, V. (with Fort, D. C.) (2004). Soteria: Through madness to deliverance. USA: Authors.

National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH]. (2010a). Schizophrenia. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia/complete-publication.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH]. (2010b). How is schizophrenia treated. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia/how-is-schizophrenia-treated.shtml

Nixon, G., Hagen, B. F., & Peters, T. (2009). Psychosis and transformation: A phenomenological inquiry. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi: 10.1007/s11469-009-9231-3

Nixon, G., Hagen, B. F., & Peters, T. (2010). Recovery from psychosis: A phenomenological inquiry. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi: 10.1007/s11469-010-9271-8

Perry, J. W. (1999). Trials of the visionary mind. State University of New York Press.

Rathus, S. A. (2006). Childhood and adolescence: Voyages in development. Belmont, Canada: Thompson Wadsworth.

Read, J. (2004). Biological psychiatry’s lost cause. In J. Read, L. R. Mosher, & R. P. Bentall, (Eds.), Models of madness: Psychological, social and biological approaches to schizophrenia (pp. 57-65). New York: Routledge.

Robins, L. (1974). Deviant children grown up: A sociological and psychiatric study of sociopathic personality. Malabar, FL: R. E. Krieger Pub. Co.

Romme, M., Escher, S., Dillon, J., Corstens, D., & Morris, M. (2009). Living with voices: 50 stories of recovery. Herfordshire, UK: PCCS Books.

Satcher, D. (1999). Etiology of schizophrenia. Retrieved, from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/chapter4/sec4_1.html

Schore, A. N. (2002). Advances in neuropsychoanalysis, attachment theory, and trauma research: Implications for self psychology. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 22, 433-484.

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, J., Alakare, B., Haarakangas, K., Keränen, J., & Lehtinen, K. (2006). Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: Treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies. Psychotherapy Research, 16(2), 214-228. doi: 10.1080/10503300500268490.

Siebert, A. (1999). Brain disease hypothesis for schizophrenia disconfirmed by all evidence. Retrieved from http://psychrights.org/states/Alaska/CaseOne/180Day/Exhibits/Wnotbraindisease.pdf

Slade, A. (1999). Attachment theory and research: Implications for the theory and practice of individual psychotherapy with adults. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 575-594). New York: Guilford press.

Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in psychotherapy. New York: The Guilford Press.

Whitaker, R. (2002). Mad in America. New York: Basic Books.

Williams, P. (2011). A multiple-case study exploring personal paradigm shifts throughout the psychotic process from onset to full recovery. (Doctoral dissertation, Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, 2011). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/54/3454336.html

Williams, P. (2012). Rethinking madness: Towards a paradigm shift in our understanding and treatment of psychosis. San Francisco: Sky’s Edge Publishing.

Woodruff, P. W. R., & Lewis, S. (1996). Structural brain imaging in schizophrenia. In S. Lewis & N. Higgins (Eds.), Brain imaging in psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

This is very good.

I agree with most of it. I think “hearing voices” should/could be described in less passive terms, if one wants to change people’s minds about the medical model. Self-conversations that one doesn’t attribute to coming from oneself, is more like it. Or self-conversations disowned, character narratives involving internal conversations between self-generated speakers, is more like it.

There is a reason these thoughts are conversations and “voices” instead of the sound of jet engines, or car-crashes. They have to be voices, and talking, and conversations, because that is how we think, in narratives and words. Of course, the rare exception would be if the trauma had something to do with a car-crash or jet engine.

My point is, when the “hearing voices movement” doesn’t explain this, and just uses language that is so, well, passive, it tends to be interpreted in the public’s mind as “auditory hallucination caused by a brain disease”, now I ask, if it is an “auditory hallucination”, why wouldn’t it be a jet engine noise as often as it is a persecutory conversation? Of course, there is much more to the story than just the simple and passive, “hearing things”, what is heard most is words, conversations, and these are actively participated in, and are a thread of the narrative that the individual is running in their mind in this crisis, or just daily life.

We all talk to ourselves, and hear our own mental “voice” all the time, it can be a strategy to disown a portion of this inner self conversation and assign its origin “elsewhere” as in, to “a voice”, or “one of several voices”, but just generally, I feel the so called “hearing voices movement”, has done a very poor job at communicating these facts, and has left themselves open to appearing dangerous, as if to appear under the control of external forces, using such passive language as “hearing”, when it is in fact a “participation” also. I think the stigma and mainstream media Hollywood narrative around people with psychiatric labels being controlled by “voices in their head”, could potentially be fueled and fed, in a damaging way, by the continued, deepening, and firming of the passive language of that the “hearing voices” movement uses, I’m also concerned about this exceptionalism that creeps in, as though people with psychiatric labels are a special breed apart, as though every human being doesn’t have conversations with themselves, or every child too, I know to some extent this movement has tried to point out that it is a “common experience”, I would say this is where I disagree most with the hearing voices movement, I say inner voice is a universal experience, it is just that only people with psychiatric labels are the ones who mostly seem to disown these inner voices, fall into the strategy of disowning them, disembodying them from their own inner voice, splitting them off into character narratives and conversations of more degrees of separation that the most people’s inner voice.

When the mainstream public hears of a movement trying to normalize so called “auditory hallucinations”, they think of a brain auditory system gone haywire, and think of biology, hearing, ear drums, and brains, and a chaotically diseased brain randomly throwing up all sorts of sounds and noises. When in fact this is not the case at all, these are narratives and conversations with oneself and conversations with thoughts and disowned character narratives about your internal narrative.

People who wind up being labeled by psychiatry with the “psychotic” label, tend to conversationalize the inner narrative of the mind a lot more than the average person, but I really do worry sometimes about what choosing to use the passive phrase “hearing voices” is doing to us. It seems to also contain an element of potential for its own self-fulling prophecy.

I had been marginally aware of your book, hadn’t read it, but after this article, it appears to be a must buy.

The first 75% of this article, is among the top 20 short form pieces of writing on this I’ve ever seen. It’s tight, taut and carefully organized prose. I’m not a fan of butterfly analogies though.

When the mainstream public hears of a movement trying to normalize so called “auditory hallucinations”, they think of a brain auditory system gone haywire, and think of biology, hearing, ear drums, and brains, and a chaotically diseased brain randomly throwing up all sorts of sounds and noises. When in fact this is not the case at all, these are narratives and conversations with oneself and conversations with thoughts and disowned character narratives about your internal narrative.

“The British Psychological Society (the BPS, Great Britain’s counterpart to the American Psychological Association), in its official report summarizing their understanding of “mental illness” and “psychotic experiences,” concluded that the various psychotic disorders may more appropriately be classified as variations of one phenomenon, a phenomenon that many have suggested we refer to simply as psychosis or madness.”

How about they are variations on the phenomenon of THINKING! Everybody thinks thoughts sometimes that are, some of us, at various points, more extreme thoughts. I’m never going to identify as “psychotic” or “mad”. Each of those words are hate-speech to my ears, ears carefully honed after years of saturation in degrading stigma.

The experiences that get labeled “psychotic” are indeed not brain diseases. And while point by point refutations of psychiatry’s crap are necessary, one simple, taut, and elegant proof is available to every single human being in the world if they want to personally test psychiatry’s insight into the brain:

Take yourself to a psychiatrist and ask him to examine your brain. When you leave his office brain unexamined, as millions before you have, just reflect on that for a moment, reflect on the fact that this quack never examined your brain, or your genes, and then ask yourself, if this profession has any special insights into how YOUR brain is functioning. It doesn’t.

If anything you’ve read above in this article (not this comment) is news to you, and you are starting to be convinced this profession (psychiatry) can’t prove distressed people have brain diseases, it might be decent of you to reflect on the fact that your government, in your name, forcibly confiscates the brains of many of your fellow citizens and hands these brains, over to this quack profession (while the person is living and conscious), it’s called forced drugging. It’s abhorrent, horrific and the most invasive thing your government does to innocent people by force as a matter of public policy. It is horrific to live through, it traumatizes its victims for life, and it must stop.

Report comment

“How about they are variations on the phenomenon of THINKING!” — I so agree. As I, in part, do with your criticism of the HVN (which I’m a member of). The point is, the HVN has, at least to some extent, the same problem that “the movement” in general has: its members represent all kinds of views on their experience. So, when you, as a member of the HVN, state that you view your experience of hearing voices as a way of thinking, there will always be a number of other HVN members who will tell you that they view their experience in a different way, that they don’t quite agree. On the other hand, the HVN still stands somewhat stronger than “the movement” in general, because its official message is that the experience of hearing voices, no matter how it otherwise is interpreted, is a meaningful one seen in context with the person’s life story. While “the movement” in general can’t even agree on the basics, i.e. whether to believe in meaningless brain diseases, or meaningful reactions to life.

Report comment

Thank you. I agree the HVM has done a lot of good. I am just concerned about this message of passivity versus acknowledging active participation in the internal conversation.

That is the first time I’ve ever tried to write anything about the HVM, I could be clearer if I spent more time on it, but since it kind of stuck out at me when I read the original article above, I thought I’d throw in my two cents.

Report comment

Thanks for sharing your important thoughts and insights.I really appreciate your desire to “normalize” experience such as hearing voices.

You may already be aware that there is some interesting research that, for many people who hear voices, some research has shown that micro-movements are occurring in the mouth/jaw muscles that seem to match the words the person is hearing. This suggests that, at least for some people, the voices they hear most likely really are just their own inner speech (that we all have, as you say), which has merely become mistaken as coming from a non-self source (i.e. has become ego dystonic).

On the other hand, when we look more closely at the recovery research, we find that for many people, what’s most important is that they have the freedom to personally explore the meaning of their voices or other anomalous experiences and develop the meaning that personally resonates for them, even though this process of meaning-making is often ongoing.

Also, it does seem true that for some people, hearing voices may stand alone as a simple and relatively self-contained anomalous experience, and simply learning to recognize that they’re mistaking their natural inner speech as being something alien to the self is enough for them to make peace with this experience and regain relative wellbeing. However, for many other people, hearing voices is merely one manifestation of a deeper struggle or split occurring within one’s psyche. In this case, hearing voices may be merely one sign that a powerful transformative process has begun and that it requires some resolution in order for the person to regain a sense of real peace in their life — this brings us to the idea I tried to illustrate with the “butterfly metaphor” that you weren’t particularly fond of 🙂 Using the “sanity/madness continuum” (Figure 3 in the article), we could say that the former individuals would be somewhere in the second or upper part of the third categories listed next to this continuum, whereas the latter individuals would be deeper into the third or even fourth categories. You can find one good example of a person in this latter category in Chapter 24: “The Case of Cheryl.”

Paris Williams

Report comment

I agree. I look forward to reading your book!

Report comment

Regarding psychosis, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classifies psychotic illnesses as “Psychosis Due to General Medical Conditions”, and “Substance Induced Psychosis”. (DSM-IV Codes 293.81 & 292.11).

Psychosis Due to a Medical Condition involve a surprisingly large number of different medical conditions, some of which include: brain tumors, cerebrovascular disease, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Creitzfeld-Jakob disease, anti-NMDAR Encephalitis, herpes zoster-associated encephalitis, head trauma, infections such as neurosyphilis, epilepsy, auditory or visual nerve injury or impairment, deafness, migraine, endocrine disturbances, metabolic disturbances, vitamin B12 deficiency, a decrease in blood gases such as oxygen or carbon dioxide or imbalances in blood sugar levels, and autoimmune disorders with central nervous system involvement such as systemic lupus erythematosus have also been known to cause psychosis.

A substance-induced psychotic disorder, by definition, is directly caused by the effects of drugs including alcohol, medications, and toxins. Psychotic symptoms can result from intoxication on alcohol, amphetamines (and related substances), cannabis (marijuana), cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, phencyclidine (PCP) and related substances, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, and other or unknown substances. Psychotic symptoms can also result from withdrawal from alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, and other or unknown substances.

Some medications that may induce psychotic symptoms include anesthetics and analgesics, anticholinergic agents, anticonvulsants, antihistamines, antihypertensive and cardiovascular medications, antimicrobial medications, antiparkinsonian medications, chemotherapeutic agents, corticosteroids, gastrointestinal medications, muscle relaxants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, other over-the-counter medications, antidepressant medications, neuroleptic medications, antipsychotics, and disulfiram . Toxins that may induce psychotic symptoms include anticholinesterase, organophosphate insecticides, nerve gases, heavy metals, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and volatile substances (such as fuel or paint).

The BMJ published guidelines for Best Practice Assessment of psychosis, accordingly, even the routine use of over-the-counter cold medicine can induce a psychotic episode clinically indistinguishable from paranoid schizophrenia.

http://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/bmj-best-practice-assessment-of-psychosis/

Report comment

I’ve seen you copy and paste the same long-winded list on this site before. Perhaps next time you could come up with something specifically for our comment conversation instead of copying and pasting the entire contents of your blog.

The mental confusion this list of drugs might contribute to, is by no means the same thing just because the BMJ, or you, decided to label it all “psychosis”.

Next time a simple link to your blog, which you have included, would be better than pasting every word that can be found at that link.

Report comment

Dear Anonymous,

Thank you for pointing out that you find my comments long-winded and that you do not feel they are specific to your comment conversation. I rarely post comments on this site so I am a bit surprised that you seem to have taken such offense to posting this information.

Please accept my appologies as I will try to clarify my position for you and why I would feel it is important to distribute this information on a post regarding schizophrenia/psychosis and brain disease.

My goal as a mental health advocate is to create awareness of underlying medical conditions and substances that can create what appears to be a manic/psychotic state and can lead to an individual being MISDIAGNOSED as having bipolar disorder/schizophrenia. As an advocate, I also support the Participatory Medicine movement in mental health care.

“The mental confusion this list of drugs might contribute to, is by no means the same thing just because the BMJ, or you, decided to label it all ‘psychosis’.”

I am not a mental health professional and I am not responsible for labeling psychotic disorders. The BMJ is just a journal and is not responsible for labeling psychosis either. Information regarding medical conditions and substances that can induce psychosis/mania is listed in the DSM, unfortunately it is ignored by most mental health professionals.

The mental confusion caused by this list of drugs might be MISDIAGNOSED as bipolar disorder/schizophrenia by a medical professional, this is why I feel it is important to try and create an awareness whereever and whenever possible.

Advocacy is needed to prevent individuals with mental confusion because of these underlying conditions from being misdiagnosed “mentally ill” and mistreated with psych meds.

“A best practice is a method or technique that has consistently shown results superior to those achieved with other means, and that is used as a benchmark. In addition, a ‘best’ practice can evolve to become better as improvements are discovered”

The British Medical Journal is a trusted source of information and the best practice guidelines they have established to assess the mental confusion that presents as psychosis support integrative psychiatry, functional medicine and an Orthomolecular approach.

If an individual is suffering from mental confusion and what presents as psychotic/manic state and seeks treatment, often they are labeled as schizophrenic/bipolar and very little testing is done to rule out underlying causes.

I copy and paste the entire list of underlying causes where I think it is appropriate so that key words and phrases are available for those searching for information online.

My main goal is to get the key words and phrases out there to help individuals who might be helped by this information, as I was.

I did not realize it would annoy individuals like yourself who do not care about this information. A simple copy and paste is quick and easy as it is rather time consuming to elaborate with a comment and usually leads to long-winded point-counterpoint discussions.

Certain individuals may be misdiagnosed and entitled to malpractice, or worker’s compensation, as well as alternative therapies paid for by their insurance company.

For example, if an individual is suffering from symptoms that appear to be mania/psychosis because of past exposure to lead, they should be entitled to chelation therapy paid for by their insurance.

In my opinion, mental health advocates should be fighting for the rights of patients to be provided alternatives paid for by their insurance companies. I feel the gateway for this is through integrated care, which the APA appears to be embracing.

I created the blog linked above as a way to collect peer-review articles and case studies that recognize underlying causes of what presents as psychosis/mania because this helps support cases of malpractice and worker’s comp. I started collecting articles during my own worker’s comp case and putting them on a blog just seemed easier to share them with others who were pursuing worker’s comp cases from toxic exposure.

With so many bloggers adding content, the Mad in America site generates a lot of hits. I don’t think many of the writers support integrative psychiatry, functional medicine, an Orthomolecular approach, or even mention the work of Dr. Abram Hoffer.

Considering the diverse perspectives and conflicting opinions in mental health care, acknowledging a best-practice approach is fundamental.

Once again, my appologies. For my own worker’s comp case I dug through the medical library the old fashion way. Since then I have helped 5 other individuals who were originally labeled with bipolar disorder establish worker’s comp cases because of long-term chemical exposure. That may not seem like much but it’s better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.

Below is a link to a narrative I wrote that outlines my position further.

Kind Regards,

Maria Mangicaro

http://www.jopm.org/perspective/narratives/2011/03/28/psychosis-possibly-linked-to-an-occupational-disease-an-e-patient%E2%80%99s-participatory-approach-to-consideration-of-etiologic-factors/

Report comment

I have similar thoughts to you on the subject, but I occasionally take heat from some of the bloggers, myself, usually because they’re unfamiliar with the subject you’ve been writing about, perhaps because they devote a lot of energy going after psychiatric pseudo-medicine with all its arcane disorders of one kind or another.

Report comment

I think that your comment brings up an interesting point that would be important to further explore: How exactly do we distinguish the distressing/limiting anomalous perceptions and beliefs (so called “delusions” and “hallucinations”) that occur in correlation with well known physiological disorders such as Alzheimer’s, certain types of strokes, traumatic brain injury, etc., etc. from the anomalous experiences that are correlated with the so called “psychiatric psychoses” that have not so far been correlated with clear physiological disorders. And is such a distinction possible or even helpful?

My own thoughts on this are that the existential dilemmas I refer to in the article are essentially universal and always present, so long as there is consciousness, regardless of serious physiological disorder or lack thereof. However, as I alluded to in the article, it appears that certain stressors (some predominantly physiological and others predominantly psychological) may make one vulnerable to being overwhelmed by these dilemmas. For the relatively “healthy and well functioning” individual, our constructs/personal paradigm do quite a good job of keeping these dilemmas mostly out of the conscious mind and relatively tamed. However, powerful stressors can rock the boat, so to speak, and then we suddenly found these dilemmas flooding into our experience, resulting in our psyche resorting to desperate strategies to cope with these and attempt to re-integrate them.

I spent some time working in a regular (non-psychiatric) hospital, on the post-acute ward filled with people suffering from severe physiological and neurological disorders (Alzheimer’s, strokes, etc.). And I realized that many of these people were indeed struggling with these same core existential dilemmas. The main difference I saw between these people and those diagnosed with “schizophrenia” or the other major “psychiatric psychotic disorders,” was that in those with neurological disorders, they were also struggling with experiences clearly caused by some damage in the “wiring,” such as various types of paralysis, aphasia (inability to speak), significant memory deficits, sensory deficits (blindness, tactile disability, deafness, etc.), etc., many of which were not likely to improve. Those who have been diagnosed with a “psychiatric psychotic disorder” are fortunate in that they generally don’t struggle with these other kinds of physiological deficits, and so have the potential to return to the level of functioning/wellbeing that existed prior to their psychosis (or even beyond that).

In short, then, I believe that there are core existential dilemmas to which we’re all dealing with all of the time (although for most of us, these are primarily unconscious), regardless of one’s degree of physiological functioning. Then, separate from this although certainly in interaction with these, physiological and neurological disorders add their own set of problems, though these other problems certainly interact with one’s struggle to maintain peace with the various existential dilemmas.

One final caveat: I believe that for the sake of effective communication and providing support for people in need, such distinctions are important. But I believe it’s also important not to lose sight of the profound interdependence of all aspects and experiences that occur within a living organism.

Report comment

My God. I really need to buy your book now.

Listen I uncharitably told this lady to stop repetitively copying and pasting her thing about this, maybe I could have been more police. But I have seen that exact same text, multiple times on other articles, with zero further tailored comment from this person, so I just told her to expand what she had to say next time. The comment I left had been bothering me.

But your answer. Was 98% perfect.

You addressed physiological and neurological disorders, in the lady’s pasted and extensive list of things, you didn’t address drugs.

What is your opinion about the contribution of drugs to thoughts/actions, and responsibility.

This site plays host to a number of writers and readers who believe that psychiatric drugs cause suicides and massacres.

I have long asked them why they believe in the power of drugs to cause people to make the choice to kill themselves, but not in the power of drugs to cause someone to purchase an automobile. Bear in mind, in recent days we have had plenty of people on this site claim that the Colorado shooter, who planned his attack for months, falls into this category. I mention this to head off at the pass any question you might have about impulsive actions.

Report comment

Thanks for bringing up the “drug” issue, which of course is complex and diverse. Regarding the correlation between certain types of psychoactive drug use and psychosis (especially stimulants, marijuana, and hallucinogens), from the perspective of the model I’ve presented here, I would say that these kinds of drugs can loosen one’s cognitive constructs, which can be both beneficial when used carefully (there has been significantly hopeful research on the potentially therapeutic benefits of LSD therapy, for example), and potentially harmful when not (e.g., the potential for leading to an overwhelming “psychotic” condition).

Regarding the topic of the harms and benefits of antipsychotics for those experiencing psychosis, here is a concise summary of what I believe are the most relevant findings from the research:

• The use of antipsychotics helps reduce the positive symptoms of psychosis and the associated distressing emotions for many people in the short term (during the first six weeks or so).

• The long-term use of antipsychotics increases the likelihood of the development of a chronic psychotic condition and significantly reduces the likelihood of recovery, as well as carrying the high likelihood of causing other serious physical, cognitive, and emotional impairments. The specific effects of such use clearly vary significantly from one individual to another, but generally speaking, this has been a strikingly consistent and reliable finding.

• Those individuals who are never exposed to antipsychotics have the highest chance of recovery.

• Regardless of the treatment method, it seems that there is always some percentage (although relatively small—apparently about 15%) that is likely to remain in a chronic psychotic condition indefinitely.

• The medical model paradigm, with its associated beliefs of brain disease and terminology such as “mental illness,” can significantly increase stigma, fear, hopelessness, and other associated distressing emotions and behavior.

• Residents of so-called developing countries have much higher recovery rates than those in so-called developed countries, and the use of antipsychotics and the medical model paradigm of treatment is inversely correlated with recovery rates.

• Residential facilities that offer continuous empathic support and freedom, and which minimize the use of antipsychotics, have demonstrated the ability to provide significantly better outcomes for their residents at significantly less cost than what the standard psychiatric model of care has been able to provide. However, these alternative approaches may reduce some personal benefits for many professional caregivers and others in the psychiatric drug industry (e.g., personal income, job security, sense of order and control in the environment, etc.), and it is likely that this is a major factor in our mental health care system’s resistance to change.

Paris Williamsw

Report comment

“Regarding the correlation between certain types of psychoactive drug use and psychosis (especially stimulants, marijuana, and hallucinogens), from the perspective of the model I’ve presented here, I would say that these kinds of drugs can loosen one’s cognitive constructs, which can be both beneficial when used carefully”

I’m more interested at this point in your opinion of the contention that psychiatric in and of themselves, cause, violence and suicide.

Not weed or LSD, psychiatric drugs.

Thank you.

Report comment

Regarding the correlations between violence/suicidality and the use of antipsychotics, here is some relevant research to consider:

Recent research suggests that schizophrenia patients who are given antipsychotic treatment today commit suicide at a rate twenty times higher than that of schizophrenia patients prior to the introduction of antipsychotic treatment. This is an astonishing figure, and it is important to keep in mind that this represents a correlation, and not necessarily causation; nonetheless, given the magnitude of this correlation, it would be difficult to deny that antipsychotics almost certainly play a significant role in this greatly increased suicide rate.

Regarding violence, akathisia is a term used to describe the condition in which one feels overwhelming agitation and restlessness on the inside while feeling trapped in a body that is heavily sedated and unresponsive, a common side effect of antipsychotic drug use. Those who have experienced akathisia often describe it as the most severe torment, the severity of which is virtually impossible for those who have not experienced it to fully grasp. Research has shown high correlations between akathisia and suicidality, homicidality, and other violent behavior.

For further discussion of the link between violence and psychosis/schizophrenia, and between violence and the use of antipsychotics, I recommend listening the following interview with Robert Whitaker on “Madness Radio”:

http://www.madnessradio.net/madness-radio-2006-10-11-robert-whitaker-violence-and-madness

Regarding the link between the recent Colorado massacre and the “medical model” understanding of psychosis/schizophrenia, I recommend the following blog post by David Oaks of MindFreedom Interational:

http://www.mindfreedom.org/mfi-blog/2012/07/21/holmes-biomarkers-psychiatric

Paris Williams

Report comment

That is a good answer. I still say those who are quick to blame heavily planned and clearly not impulsive crimes on drugs, are jumping the gun.

Clearly too, there is much more hopelessness injected into the lives of people labeled SZ and this and many other facts should be factored in to the increased suicidality.

I have experienced akasthisia, it was an unpleasant sensation, but I retained my ability to see right and wrong, and didn’t commit a massacre.

Report comment

One of the things most of the bloggers don’t know, is that the various attempts by mainstream guys to understand psychoses came from attempts to disprove another biological notion- that the syndrome isn’t a brain disease at all, but a metabolic disorder in which one’s own body produces hallucinogens, especially under stress, which can come from any number of stressors.

Report comment

Sean Blackwell also has an interesting perspective on bp/schizophrenia

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Db8AYSrs2kk&list=PLC41AE6B1DB0C0EA0&feature=plcp

Report comment

Thanks for your great work, and for sharing it here. I haven’t read your book yet (but did order it).

I am very convinced by everything you say, and your model seems powerful when applying it to at least some “mad” people I have befriended.

You associate delusions with a loosening of cognitive structures (during some crisis). I would say it is important to distinguish unstable breaks with reality (corresponding to a loose structure with no self-consistency over time), from very stable delusions (possibly lifelong) that form an extremely logic/rational/self-reinforcing perception of reality (and that can develop in a rational non-traumatic way) with hardly any more contradictions that “consensus reality” (I love that expression).

For instance, some paranoid people are often very logical/rational/intelligent, and have developed a dog-eat-dog model of their environment that is hard to disprove without the possibility of mind-reading (any act of good-will is seen as being a conscious and purposeful malevolent grooming-manipulative act), and don’t have significant dilemmas about their place in it.

Report comment

Thanks for your comment and insights–these are important points.

I briefly refer to the distinction you suggest (relatively stable/even lifelong anomalous experiences vs. relatively unstable experiences)in Figure 3 of the article, suggesting this distinction as not being black and white but perhaps lying along the “sanity/madness continuum” from the second to the fourth categories.

I also go into this distinction in much more detail in my book, Rethinking Madness, and give specific case examples to draw a distinction, while also not losing sight of the continuum nature of this and also the relative nature of this. For example, we can argue that members of one religion, political orientation, or culture may appear to maintain long-term “delusions” to members of a different religion, political orientation or culture. Yet there is clearly something a little different going on in this case than with someone whose constructs of reality are clearly quite loose and fluctuation in a fairly wild manner (so called “florid psychosis”). And there’s something to be said for questioning the health of people on both ends of this spectrum–those experiencing particularly loose cognitive constructs on one end, and those experiencing particularly rigid and dogmatic constructs on the other.

Paris Williams, PhD

Report comment

Hi Paris,

Wow! What a pleasant surprise to wake and find this substantial op-ed piece, after re-reading your Doctoral Dissertation last night. I really appreciate your efforts to bring our focus of attention onto what the experience of psychosis actually is, instead of the usual focus on how to treat an assumed illness.