Thousands of books are published every year on parenting. Bookstore shelves buckle under the weight of books covering almost every situation imaginable – parenting disabled children, parenting children in gay families, parenting children according to gender, ethnicity, medical condition, personality, even parenting your child before birth.

There are no books on parenting dead children.

Ask any mother whose child is dead if she stopped loving them when they died. Ask her if she stopped being her child’s mother. Ask her if finding ways to continue to parent her child after death is part of her reality but a part she generally can’t talk about for fear of being judged or pathologised.

My only child is dead. If I am not his mother, I am not a mother at all and that is not a position I will ever accept. My role as his mother is not something I am willing or able to let go of. If I had a dozen other children, I would still need to be his mother, I know I would.

There are events other than death that force us to find new ways of parenting our children. A child who relocates overseas, a child who marries, a child who goes to prison, these children cannot be parented the way a child living at home with you would be parented. Following any of these events a parent is forced to learn to parent their child differently but most don’t consider ending their role as active parents. Only death it seems is expected to make us relinquish our role as parent.

Toran is dead but he is still my son and I am still his mother. I still want the best for him. I want to support and care for him, to advocate for him and further his interests. It would take more than death for me to let go of being Toran’s mother and of actively parenting him.

Before Toran died, I would have said that dead is dead. That dead people no longer exist except in the memories of those still living. I would have said that dead people are no longer people. But when he died, I found myself asking where all that energy, the laughter, the noise, the demands the love could have gone. And I began to question my beliefs and wonder if it is possible for consciousness to survive death. Five years and hundreds of books on quantum theory later, I am equivocal. I simply do not know whether Toran still exists but, just as if he was a missing child and I did not know whether he was alive or dead, I cannot give up hoping that he survived and continuing to work in his best interests. I am comforted that the brightest physicists in the world say we only understand around 3% of the physical universe and that we cannot rule out the possibility of life after death.

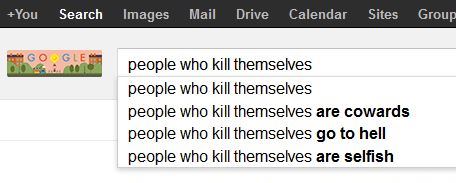

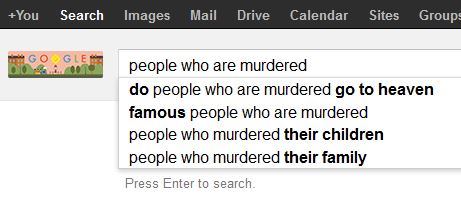

Being the parent of a dead child is hard. Being the parent of a child who died from suicide may be even harder. It seems so to me when I look at how google autocompletes for two searches – people who kill themselves and people who are murdered.

You will see that one is focused on information gathering while the other seems to believe that suicide victims being cowardly, selfish and hell-bound is fact.

The New Zealand guidelines on media reporting of suicide state that reporters should not “Just focus on the person’s positive characteristics.” It is hard to imagine guidelines that suggest reporters find negative things to say about those who die from any other method.

I know my son was not a coward, that his death was not selfish and that he is not being punished for ending his life. As his mother I cannot allow those attitudes to go unchallenged. I wouldn’t if he was alive and I won’t because he is dead. Protecting his reputation, defending him from defamation is one of the ways I parent him after his death.

I have found other ways. Toran was born on Mother’s Day and on that day I make his birthday cake. Does he care? Does he even know I painstakingly mold fondant cats and stars, coke bottles and bowls of popcorn for him? I don’t know. But mothers wrap Christmas presents for babies only weeks old even though they don’t know or care, because it is a way of expressing love and experiencing motherhood. And maybe he does know and would know if I didn’t do it. Maybe he experiences happiness and pride in his mother’s love and commitment to him. Maybe. Maybe not. I don’t know.

In my car, I have a laminated photo of him which, if placed correctly reflects his face in the windscreen. When I’m on my own in the car, I can look at him and talk to him and sing his favourite songs when they come on the radio.

Toran’s song is the R Kelly song “I’m that Star Up in the Sky.” At night, I find the brightest star and I talk to him. I tell him how scared and lonely and unsure I am, I tell him how much my soul longs for him. I thank him for helping me during the day. I ask him for signs that I’m doing what he wants me to do. I tell him how beautiful he is and how proud I am to be his mother. I do things in his name. I try to be kind because kindness mattered so much to him. (I don’t try to be cool because even though that mattered a lot to him too, he was very clear that it was something I would never achieve and was clear I should not even try).

Mainly what I do is try to change the world in his name. I try to create a world in which he would have been able to live rather than die. To that end, I started a charity that supports families bereaved by suicide and challenges thinking in medical and policy circles on how we treat distressed people and prevent suicide.

I get to say his name every time I run a suicide prevention education session. I get to tell his story when I file submissions on government policy. When I am contacted by a parent who has lost a child to suicide I sit on his bed and tell him all about the family. I tell him “Toran, I found the mum, can you go and find the child and can we support this family together.”

In my work, I try to help parents find something that they would like to achieve in their child’s name. Often it is a change in legislation or policy which is meaningful because of the way their child died. Sometimes it is a project, an artwork, travel, establishment of a foundation. And sometimes the parent finds a way their child can work with them on the project like with me and Toran and CASPER, and that is magical.

I love my son and am proud of him and work to make sure that his having lived makes the world a better place. That is how I parent him. Being his mother is like breathing to me and is something I will be and do until I take my last breath. And maybe beyond. Who knows?

If you too are the mother of a dead child, particularly one who died from suicide, then before you accept people’s assessment that you are ‘in denial’ or suffering ‘prolonged grief disorder’ know that there are other mothers out there for whom parenting their child after death is part of their new normal. Mothers who nurtured their children’s bodies and continue to nurture their souls.

“Mainly what I do is try to change the world in his name. I try to create a world in which he would have been able to live rather than die. To that end, I started a charity that supports families bereaved by suicide and challenges thinking in medical and policy circles on how we treat distressed people and prevent suicide.”

As a mother and grandmother myself I admire the work you do to inform and support others Maria. You are indeed part of the change we want to see in the world! You are an inspiration to all mothers! Thanks so much!

Report comment

Your article is amazing and you remind me of the strongest woman I know, My Mom. She too lost a child to car accident and this what she had shared to congregation of bereaved parents. You and my mom share similar views, i think: http://www.bpusastl.org/andrew.htm. Thank you for the work you do, I have not experience a loss of a child, but I have seen the devastation and if it were not for people like you, us siblings may have lost our parents.

Report comment

Thank you so much for sharing your mum’s writing with me. I connect with everything she says – that’s my life too. I would so love to sit down and have a coffee with her! Just reading her post made me feel so less alone. Tell her thank you 🙂

Report comment

Will Do! thanks

Report comment

Touching and inspiring!

No doubt Toran’s death was an act of great courage, a sane response to the pressures that he was under. It is beautiful to see that you love him and continue to parent him despite the pain of loosing him.

Thank you for reaching out to change the world.

Report comment

Maria, the last few things you wrote, making fun of psychiatrists, really made me laugh. This article made me cry.

You are a good writer, and obviously a good human being. I love your honest expression of what you feel. I hope our paths cross in person some day.

Report comment

I read things like this and realize “prolonged grief disorder” and other similar atrocities should be stricken from the language. I am proud I no longer study or practice the DSM.

Report comment

Maria,

I pray for people who are alive, and I ask them to pray for me.

I do the same for those who haved passed away from this earth.

And I will keep both you and your son in my prayers.

Duane

Report comment

Maria,

One day, our paths will cross from my home in CA to yours in NZ. You have read the story I share in MIA about my beloved 25 y/o beautiful son, Shane, who like Toran, left this earth too prematurely and for reasons we simply will never fully know. But the mental health system in both our countries is a tainted, pathetic, and often corrupt industry. Like you, I believe had my family and I not taken Shane to a psych hospital or p-doc believing he would receive compassionate care and support as he was experiencing a NERVOUS breakdown ( the most accurate description of what Shane experienced) due to a ” sea of stressors” and his reaction to using cannabis. Instead of understanding the human psyche, evaluating the emotional trauma and helping educate my son how chemical substances can alter the mind- just rush to dx with a severe MI, massively over drug with ” criminal” doses of multiple neuroleptics, warehouse and abuse. (Sadly, the knowledge base regarding today’s genetically altered marijuana seed with its ever increasing high octane THC which is causing the psychosis link in some young brains is lacking in society, including and especially the so- called “experts”). But link to ” cannabisandpsychosis.ca” a Canadian interactive website and the word is finally being told!

No matter now, our beautiful sons are gone. We Moms carry and bore these children. I felt my son die that fateful day in Jan, 2012. Of course, we will forever miss their presence, the world should have been their oyster! We Moms will continue to keep their memories alive, and try to make this crazy world a better place in spite of the hole in our souls. Thank you for your grace, and the boundless love you have for Toran. I’d like to hope our boys with their zest for life and love for others are together somewhere rooting on their moms who championed for them while alive, so surely despite their earthly bodies are gone, we will champion the causes that took them from us!

Big Hugs,

Lori

Report comment

The selling of bipolar disorder stresses that the disorder takes a fearsome toll of suicides. And indeed the controversy surrounding the provocation of suicide by antidepressants has been recast by some as a consequence of mistaken diagnosis. If the treating physician had only realized the patient was bipolar, they would not have mistakenly prescribed an antidepressant. Because of the suicide risk traditionally linked to patients with bipolar disorders who needed hospitalisation, most psychiatrists would find it difficult to leave any person with a case of bipolar disorder unmedicated. Yet, the best available evidence shows that unmedicated patients with bipolar disorder do not have a higher risk of suicide.

Storosum and colleagues analyzed all placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trials of mood stabilizers for the prevention of manic/depressive episode that were part of a registration dossier submitted to the regulatory authority of the Netherlands, the Medicines Evaluation Board, between 1997 and 2003 [28]. They found four such prophylaxis trials. They compared suicide risk in patients on placebo compared with patients on active medication. Two suicides (493/100,000 person- years of exposure) and eight suicide attempts (1,969/100,000 person-years of exposure) occurred in the group given an active drug (943 patients), but no suicides and two suicide attempts (1,467/100,000 person-years of exposure) occurred in the placebo group (418 patients). Based on these absolute numbers from these four trials, I have calculated (see Figure S1 showing calculation, and see Figure 2) that active agents are most likely to be associated with a 2.22 times greater risk of suicidal acts than placebo (95% CI 0.5, 10.00).

More http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030185

2.22 times greater risk of suicidal acts than placebo.

Nothing further, your honor.

Report comment

Hi Maria — it is 2:33 am, I should be in bed as I teach 5th grade students in about 5 hours — I, too, lost a dear, precious son to suicide last May – and feel the same as you do. I have not read every article you’ve written, but enough to know we are on the same page.

I will finish reading this week — however, your article “How to Parent A Dead Child” and one of your other articles touched on a subject that I am going to pursue —- communicating with my son —— don’t know how —- in what medium, just know I am… I have yet to go through his personal belongings because I feel I am invading his personal space – that he will come home one day… or rather, he is still here in our home. Many people may think I am crazy — and I do not care —— I just know I’ve seen signs, smelled his scents on occassion. I recently logged into his email and saw a ‘draft’ that he composed 2 months ago —- he died last May. For the first time since his tragic death I felt a grain of hope that he is still with me. Oh – and like you, I have never been angry at my precious, kind-hearted son for what he did — I never will be angry at him —- I am angry at myself for not protecting him – or seeing the depth of his pain, etc — whatever, it does not matter at this point — I just know I’m holding to a glimmer of hope we will figure out how we can communicate during this horrible twisted journey we must now travel. Like you, my world is shattered. Will was the best , BEST son any morher could ever hope to have. Thank you for this forum. Valinda

Report comment

Valinda I am so sorry – for your loss and for Will’s loss of his life. My email is [email protected] if you want to talk. Much love, Maria xx

Report comment

Thanks, Maria —- I would love to communicate further — need to catch up on some things – school and bills — can’t complete anything these days — then, i plan to read all of your articles — also, read my son’s journals, do some research —— one thing I’ve tried (in vain, thus far) to do is to find or recover his facebook page or maybe icloud page — he had recorded himself playing the guitar and and singing a song he had written. I miss my son so badly —- I know you do as welll — I have a daughter — and I feel like she has been cheated not onl by the loss of her best friend, but with having 2 parents who are so totally heartbroken, htey can’t be ‘there’ for her. Thank you, again — for your form and yourquick reply — with contact info. valinda

Report comment

Maria have you read the “Grief into Gratitude” process in

chapter 11 ‘resolving grief’ in the book “Heart of the Mind”

by steve & Conirae Andreas ? It tells you how to keep who or

what you have lost with you in spirit .

Report comment

Dear Maria,

I’m really sorry for your loss and can imagine how intense your pain might have been.

There are many findings linking psychiatric medication to suicidality, by hindering rational thinking and causing psychosis. However, no matter what the state a person is in, there is still a power of choice involved. There was a choice made at some point by your son and other people who have committed suicide. I agree that the self-determinism involved in that choice might not have been high, it wasn’t zero either.

I appreciate the good cause you’ve started in the memory of your son, but it wouldn’t be right to talk about those who’ve died by suicide in total sympathy; it can factually set a bad example. It would even bring those people down to total effect, a not desirable state for a human being.

I wish you success in your continuous effort.

Report comment

What would motivate a person to take the time to write and publicly post such a smug, mean-spirited comment? Ew.

Report comment

Dear Suzanne,

I read your reply and Maria’s. I am sorry that my comment came across that way, I did not mean to.

At the same time, I do not appreciate some harsh judgements made on this, and toward me.

I actually have encountered the suffering brought by psychiatric medications and suicidality (will prefer not to go into details or explain whether it was first-handed or through a loved one).

Report comment

Hi Jolie. Yes my son made a choice. He chose to end the torture of antidepressant induced akathisia. Much as he would have chosen to cut off his arm had it been trapped on a railway track with a train approaching. A choice he would never have wanted to make but one over which he saw no other choice.

My son did not ‘commit suicide.’ People commit sins or crimes – his taking of his life was neither. My son died by suicide with both my government and Mylan Pharmaceuticals assessing Prozac as “the most likely cause” of his death. He was neither a sinner nor a criminal. He was a victim.

You suggest my child should not be spoken of in total sympathy. It is hard for me to imagine what about a child being tortured by medical professionals he trusted and going through the terrifying process of making a noose and hanging himself in order to end his pain deserves judgement or criticism.

I think that you are suggesting that my expressing my love and sympathy for Toran sets a bad example to others. You perhaps believe my message should be that if you kill yourself your parents will stop loving you and will publicly condemn you. You perhaps believe that this would act as a deterrent to suicide. Let me be clear about a couple of things. First, my son is not defined by how he died. He is defined by how he lived. Second, I HATE suicide. I hate what was done to Toran and I hate what he did to himself. My son was a child any mother would be proud of, his death is a death any mother would hate passionately. I will love my son forever. I will hate suicide forever. I will never condemn my son for being a victim of iatrogenic suicide.

Two years after my son died, my sister died during chemotherapy treatment and a blood transfusion. It has been acknowledged that her death too was iatrogenic. My sister could have chosen not to have treatment for the leukemia she was diagnosed with. Should i also condemn my sister for her choice? Should i stop loving her because she chose to accept treatment that killed her? Am I setting a bad example by publicly saying I love my sister?

Finally thank you for your good wishes. They are appreciated.

Report comment

Dear Maria,

I read you reply. I am sorry that my comment came across that way, I did not mean to.

At the same time, I do not appreciate some harsh judgements made on this, and toward me.

Report comment

By the way, I actually have encountered the suffering brought by psychiatric medications and suicidality (will prefer not to go into details or explain whether it was first-handed or through a loved one).

Report comment

I am sorry if it has stirred up some painful past experiences dealing with others, but please understand I was not involved in causing those.

I apologize for having made three different comments, I am still upset by reactions directed toward me, and couldn’t find an option to modify my previous comments.

Report comment

Yes, I am a mother of four…two girls and two boys. I have buried my middle children…my younger daughter (died from complications of a disease I did not know I had) and my older son (murdered).

I am parenting my living children. But my deceased children? Sometimes I talk to them. Sometimes I ask them for the courage to go on. I pray for them every day and tell them of the joy of meeting them again. But I respectfully disagree with you upon the ability to parent them. To parent is to love, guide, teach and protect…none of which you can do when a child or children has passed.

Having said that, from one mother with a hole in her heart the size of the Grand Canyon to another mother with a hole in her heart the size of the Grand Canyon, please accept my sympathies on your devastating reality. I do not say “loss” because i know Toran is always with you. And yes, my dear, you are still a mom.

Peace be with you.

Report comment

Dear Maria,

Your essay was so beautiful and brave. Thank you for generously sharing your story, offering all of us grieving moms the chance to feel less alone.

HUGS,

Lisa

Report comment