It’s been a while since I posted here on Mad in America. I come by and read, but don’t comment much anymore. For the past few months, I haven’t much felt like talking with people.

That is about to change.

My last post here was made right after a community member who was a part of our local mutual aid group committed suicide. The rest of the summer was spent in a long haze of days cluttered with emails and restless children, a wilting garden and a slow edging back into myself.

I still kept up with local organizing and started to do some work as a support coordinator with The Icarus Project, to build stronger local group organizing networks and help out with some of their plans for organizational development and an expansion of the radical mental health vision to include more people of color, queer and gender non-conforming folks, and people who identify as poor and working-class, to work across lines of disability and culture.

I’d think to myself about how remarkable it is that, three years ago, I felt as if I were one of the most isolated and disconnected people in the world and my life was – objectively speaking – on the verge of a total and final collapse. Every day, as the summer wore on, I’d count up my blessings, in friends and opportunities, my family and all my possible futures, but I felt myself getting more and more quiet; becoming exhausted.

I posted my introduction to the Lived Experience Research Network with a ½-hearted statement about my graduate studies and a musing that maybe I ought to just pack it all up and move to the woods, write stories and work toward my goal of eventually being an elderly outsider artist.

I began to notice that every time I said anything, I’d feel insecure and anxious.

I stopped posting to Facebook.

“I don’t even feel comfortable with people,” I’d tell myself. “I’m a loner, not a community builder.” However, when I read the visionary texts that I was assigned for my Transformative Social Change courses, my mind felt clear and what I have come to recognize as my heart’s truth would swing into the feeling that tells me that something is vital. Almost as if on cue, the habitual doubt that I learned in my years of people not believing in me would pop its ugly head up, sneering, “Yeah, right, Faith. Like you could really do work like this. You’ll mess it up. You shouldn’t even try.”

It shouldn’t have surprised me that I should come upon such a time of uncertainty. I am, after all, rebuilding my life, and over the past couple of years – with the help of friends and supporters – I’ve cultivated a lot of options. Sometimes, it is hard to know what to do and I find myself constantly negotiating between what people want me to be and who I am. Recovering from self-doubt and learning to claim my own potential is a matter of making the daily choice between listening to the vestigial voices of people who – in their own failure – did not see me clearly or believe in me and choosing, instead, to take chances, to challenge myself to trust those who believe in me and value me, and – finally – to believe in myself and in the world, to not give up and drop out, but to keep going, to see what happens if I try.

The death of a mutual aid collective member had shaken me and discouraged me, caused me to doubt my ability to be an active and supportive community member.

I began to avoid people who wanted to talk about the suicide. I didn’t want to talk about it. I wanted to do something about it.

Standing outside of a coffeeshop, a few collective members and I discussed what might have happened differently if our local mental health system had been more accessible and helpful to this person we knew, who had turned to those services for support; this person who – on the day before he died – plainly stated through frustrated tears that he felt “failed and betrayed” by the providers he had trusted to help him.

I understand that some people are staunchly opposed to public mental health services, and I certainly understand why. However, millions of people reach out to these organizations and agencies for assistance in getting through difficult times. It is common knowledge that the “help” they get is not always helpful, but I have definitely known a few people who found the support they were looking for in the public system and, let’s face it, until there are widely available and accessible alternatives that people are able to turn to, many people who are struggling reach out to public and private providers for help.

Regardless of what I think or feel about it, the mental health system definitely exists and, as many people know, it can do a lot of harm to people – from negligent and abusive psychiatric drugging, to mis-conceptualizing human distress as a mysterious biochemical disorder while ignoring the role of trauma/stress in wreaking havoc on our neurochemical landscapes and the power of a broken heart to wound our minds, to re-traumatizing and exploiting people who have endured controlling and manipulating relationships within their lives.

Yet, I would be lying if I said that I thought no good could ever come of publicly funded supports for people in distress. It just depends on what sort of help is offered, and whether it is actually helpful.

In that conversation outside of a coffeeshop, fellow members of the Asheville Radical Mental Health Collective and I talked about what it might take to create a peer-run respite, to have accessible and trauma-informed safe spaces where people could go if they just needed someone to listen to them or to support them in the process of learning how to heal within their lives or to find connection with people that might make severely and persistently difficult lives less lonely.

“It’d be a lot of work.” We looked around at one another.

I felt exhausted, but some small spark of inspiration was lit in my mind.

“What if we organized some talks with people in the community, gave them a chance to share their experiences and identify concerns. That might build a really strong base of advocacy.”

We stood there, four of us, and we sighed.

“If there had been peer respite or a safe space for him to go, he’d still be alive.”

I decided to hold onto that thought.

A couple of months after that conversation outside of the coffeeshop, I received an email inviting me to participate in the Peer Committee of our local Recovery-Oriented System of Care Taskforce – which is part of a coalition that developed out of a group which previously advocated primarily for quality and accessibility in substance abuse services.

Early one morning, I went to meet up with a local consultant who does peer trainings, the program director for a large private recovery community and a fellow survivor-friend, whom I met at a book-launch event and who currently heads up the local NAMI, in spite of the fact that she refrains from using the language of “mental illness.”

“What am I doing?” I wondered, as I walked into the inhospitable building that houses both the local NAMI and the local MH/SA/DD funding management entity – all located right across the street from the hospital.

I thought about Ted Chabasinski and the bus ride to Philadelphia’s Occupy APA event.

I considered all the criticism surrounding the word “recovery,” the word “system,” and the word “peer.”

Did I really want to be involved in something called the Peer Committee of the Recovery-Oriented System of Care Taskforce? Would I still be a radical? Did I even care?

What would that mean?

As a person who is interested in the processes that support transformative social change, I believe that it is important to work creatively and dynamically for change. It makes sense to me to explore advocating within the system, for the purpose of encouraging transformation of that system.

It was decided at that meeting that we would begin to explore strategies for developing alternatives, and we determined that while we would far prefer to somehow magically create a network of empowering, accessible, holistic off-grid alternatives, that the possibility of working with the system to expand high-fidelity recovery-oriented services and develop crisis alternatives was not completely out of the question.

We used words like “partnership” and “collaboration.”

Later, reading over the materials that SAMHSA has created on the process of implementing recovery-oriented systems of care, I shook my head.

It wasn’t that I was disgusted, or offended.

It was because a lot of the goals sounded . . . well, okay, if not good.

At the next meeting, my friend said, “Hey, look at this…” and turned her computer screen to show me the Creating Community Solutions website, which is the initiative that was developed to support the National Dialogue on Mental Health. President Obama called for the National Dialogue as part of the response to the Sandy Hook shootings of last December. Featured on the mainpage of the www.creatingcommunitysolutions.org page was an article about the NPR Story Corps feature that included Liza Long – of “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother” fame – talking with her son about his “mental illness.”

There was a map, with a bunch of little digital pins scattered across the states.

The National Dialogue on Mental Health is introduced with the following statement:

“The President’s plan to protect our children and our communities by reducing gun violence directs the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Education to launch a National Dialogue on Mental Health with young people who have experienced mental health problems, members of the faith community, foundations, and school and business leaders.”

Somehow, there was something in all of the decidedly grim context that, to me, shined a little.

“What might happen here if people talked about what is helpful and what isn’t?”

A big part of my recovery from psychiatry has been regaining my sense of confidence and viability as a valued member of my community and as an activist. What would happen, I wondered, if my survivor-friends and I, with other people from the local recovery community (which includes open paradigm radicals who question the implications of the word “recovery”) supported the organizing of a Creating Community Solutions dialogue here?What if we helped to organize a whole series of them?

As someone who is well-versed in mutual aid, inquiry-based education, and working with young people who are identified as being “at-risk,” it was powerful to think about people talking with one another and listening to each other, sharing ideas and hopes and fears for the purpose of potentially creating meaningful change and real supports for self-directed and strengths-based navigation of challenges with our human experience.

What if we talked about the difficult truths? For example, it seems that – for some – the circumstances of life, as set in place by economy, discrimination, and profound difficulty in their human experiences, make recovery less of an accessible option than for others.

How could we better honor those realities?

In the part of my mind that believes that something in the world is striving for good things to happen and for us to collectively find new ways of seeing one another and supporting one another in being fully human, I marvel at how convenient it was that a rag-tag group of survivors standing outside of a coffeeshop had plans that align so closely with the national initiative’s goal of bringing together diverse stakeholders in dialogue about mental health, community-identified needs and realities, and ways to support healing . . . of individuals, families, communities, and systems.

Sitting in meetings at boardroom tables, I have occasionally found myself with tears in my eyes, because I have seen that the people who work within these systems – people that I used to just think of as blank-eyed “mental health system bureaucrats” – are, themselves, deeply human. They’ve surprised me and inspired me, in both their commitment to trying to do things differently and in their support and appreciation for survivors and community members being at the table.

Community Solutions WNC is holding its first public information and organizing event this week and peoples’ interest in this initiative is encouraging. What is more encouraging, at least to me, is that I am integrally involved.

As a person who once assaulted her own mother in a teenager-on-Prozac rage and whose young potential was badly compromised by involvement in misguided treatment, it feels important to me that I be a part of this, that I support this happening in my community.

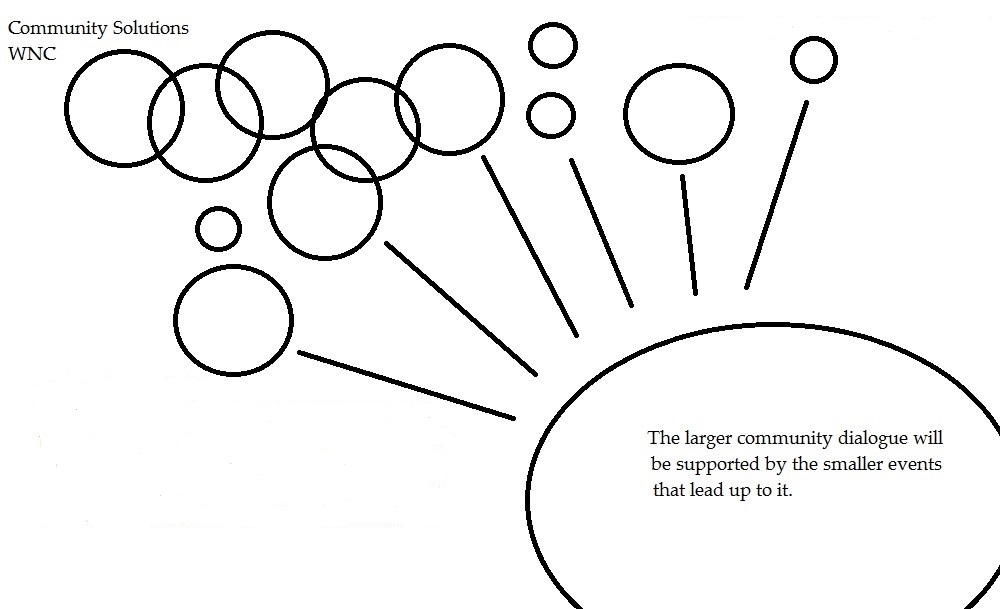

These dialogues that are being organized are interesting to me, full of both chicanery and possibility. I somewhat doubt that many of them will produce sustainable outcomes. Most of them are big, single-day events, organized by mayors and NAMI branches, schools and the United Way.

We’re approaching things a little bit differently here, because we want to talk with as many people as we can and get people involved whose lives are most affected by the policies and procedures that define local systems. We want to center this initiative around people who might be most vulnerable to not having their needs met in ways that are helpful, accessible, and culturally-appropriate. More importantly, we want to build community and find commonality while intentionally making space for people of color, homeless folks, and the LGBT community to talk about how their self-identified mental health needs might differ from the mental health needs of middle-class, white, straight-people – who are, by and large, the people making the decisions about what gets funded and why.

We want to create opportunities for people to talk about their different ideas about what “mental health” even means and what they believe about “mental illness.”

We have no interest in debating with people.

We want to talk with people.

We want to listen to them, and we want them to listen to us.

Some people call me naïve because I have an inordinate amount of faith in the innate human capacity to make good choices when given the opportunity and presented with ample evidence to support them making a decision that is informed, not only by data, but by recognition of their own individual best humanity and potential to be a force of healing and justice in the world.

I really do believe that things can be done differently, that we are not constrained by old models and that, in keeping with the workings of systems in nature, things inevitably change, especially if they don’t work.

Our local dialogues will not be organized by the mayor, or by the mental health system.

They will be organized by consumers, and survivors, and ex-patients.

Hopefully, they will also be organized by kids . . . because many of them are also consumers, survivors, and ex-patients.

When I worked as a volunteer Guardian ad Litem for teenagers in state custody, I only worked with young people who were “placed” in Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities or group homes. The very first time I disclosed my own lived experience in a way that seemed to encourage someone else was in speaking with a young woman in a locked facility. We were sitting in the recreation room and it was the second time I had met her. We weren’t sure what to talk about. I was a new GAL, a white woman with tattooed hands. She was a young black woman whose family was in shambles.

“You know,” I told her, “I was in a place kind of like this when I was a teenager. My situation was a lot different, but the place I was in was a lot like this place.”

She looked at me and smiled, asked a couple of questions and then she began to tell her own story.

Since then, she has graduated and is now taking classes at the local community college, which would be a great place to hold a large public forum on mental health in the Spring, following a series of smaller, community based dialogues.

I’ll have to get in touch with her and see if she might want to help us to organize some young people.

To me, this is radical.

————————

Community Solutions WNC is currently building infrastructure and organizing strategies. We have a Facebook page and a website that we refer to as our “infoblog.”

We are actively building relationships with community members and local organizations, including the Mountain Council Recovery Coalition, and plan on seeking endorsement from the City of Asheville.

We are grounded in the principles of participatory organizing, deliberative democracy and sustainable advocacy.

For more information, or if you know of anyone – in North Carolina or elsewhere – who may be interested in supporting this initiative through consultancy, in-kind or service (e.g. simple website design) contributions, please let us know by emailing [email protected] or calling (828) 351 4113.

Of further interest:

Faith Rhyne at last year’s Esalen conference on alternative perspectives on “psychosis.”

Faith, thanks for having Faith in change! I believe that if you see each person as a human being,as you stated you did when you teared up …. there lies potential that we can all connect at the “community table” to acknowledge what’s not working, explore alternatives and continue to evolve, including the traditional system workabees. It starts with that one person who exposes their questioning, discomfort, doubts, disagreement and this can spread to influence other colleagues. I’m watching this take place now at our county mh system and I see the change a coming! It definitely has been fostered by survivors speaking up, our Peer Respite House providing a true alternative for people to get support has been, and continues to be, a living example of mutuality rather than power dynamics, I’m the doc/ therapist, oppressive “do as I say”.

I also agree that this dialogue must be lead by survivors, having allies join, yes but the people with lived experience must take the lead!

Report comment

Thanks for reading, Yana…and for appreciating the value of trying to create spaces that “meet people where they’re at” – even if where they’re at might be currently defined by ideas or practices that I might not necessarily agree with or endorse…even if I strongly oppose – on the basis of ethics – what someone is doing, I have never met anyone who embraced a willingness to change their behavior because someone told them that they were evil. To me, change happens by making space for it and believing that it is possible and finding clear ways to get from the landscape of point A to the promise of point B.

None of this would be possible without the work of people who pushed against the walls in oppositional protest, made the cracks for the light to get through.

Report comment

“I understand that some people are staunchly opposed to public mental health services, and I certainly understand why. ”

This was a wonderful article from beginning to end, but I just want to focus my comments on this theme.

My feeling is that we who wish to strive for a better way of healing human partnerships really don’t have the luxury of just writing off public mental health service system as a lost cause. The reason I believe this is because millions of people are either forced into these systems against their will (through commitment or other means) or forced into these systems because poverty and structural inequality mean they simply have no access to anything else.

The people forced into this system are often the most socially marginalized of all persons in our society. They are the most exploited, and often the most vulnerable to that exploitation. If you had experiences that society labeled as mentally ill BUT you were also rich with a vibrant social network abundant with personal resources, your experience would be spectactularly different than if you are desperately poor with few or no supports.

So no matter what our attitude toward the public mental health system (and my own is staunchly critical, though I work in it) we need to keep the millions of persons who use and/or are stuck in this system in our hearts and minds. We need to be willing to get into that system and work in it, if for no other reason than to try and protect and support the rights and dignity of the “clients” of the system wherever we possibly can.

At the same time I think we need radical, if not outright revolutionary change, (in which they entire mechanism of state mental “health” would be dismantled and replaced by mutual-aid systems driven by persons with lived experiences engaged in deep, local collaboration with friends neighbors and community), I also feel I have a duty to be a loud voice for change within the system as it presently exists.

We need people who are willing to speak truth to a system of immense power, to challenges its evidence-absent assumptions, to question its bigotry and dehumanization of those who receive its “services.” We need to make the system uncomfortable, call “bologna” on its baseless claims, present clear, persuasive supporting evidence for a better way, and be willing to face persecution because of it, if and when it comes to that (and in my experience so far, it always does.)

We need radicals INSIDE as much as we need them outside. I believe that is the only way to undo the monster machine of “mental health” as it currently exists and create a path toward something better.

Report comment

Andrew, I couldn’t agree with you more! As another ally working within…I am comitted to this population who indeed are in the socio-economic group of often poverty and without family/friends or natural supports and resources…change happens from within

yana

Report comment

Faith,

I’m gonna go way out on a limb here…

When it comes to the public mental health system, *as it exists to a large extent today in most parts of the country*, I think it might be better to do *nothing*…

That’s right, I honestly believe it’s better to do *nothing* than to get a psychiatric label, a boatload of drugs and “treatment” as the system exists today.

Simply put:

“To do nothing is sometimes a good remedy.” – Hippocrates

Thankfully, people like *you* are changing things.

Keep up the great work!

Duane

Report comment

Hey, Duane – Thanks for saying hi.

I agree that the damage done by reductionist and formulaic treatment is – in moderate terms, problematic…honestly speaking, grievous.

Which is why I feel like I have to try to do something.

🙂

It’s not people like me who are changing things, it’s people like you and me and *a whole lot of people* – at every level, working with a lot of other people, building on the work of people who have come before us…that are *trying* to change things.

It’s people with signs and people in suits and people in plainclothes meetings over coffee and sitting in front of their computers and talking with their neighbors.

Thanks for reminding me of the power of doing nothing…that is actually something I remind myself of a lot, in pacing and in timing.

Sometimes, I get caught up in wanting change to happen immediately and I have to remember that anything that is lasting takes time to build. These systems and the ideas that drive them took time to develop and they take time to change.

Thanks for being out there…

Report comment

I need to clarify for a moment.

What I was trying to say was that it may be better for a person suffering from “symptoms” to do “nothing” rather than enter into the current mental health system. In other words, there is strong research to show that “natural recovery” takes place quite often, sometimes even “spontaneous recovery.”

I was not trying to say that those of us who are working to change the system should do nothing. Also, I was not saying that we should stop doing our best to make a paradigm shift take place in this shattered model we have today.

Duane

Report comment

Apologies for the confusion.

Best,

Duane

Report comment

Duane,

In my opinion, that is a philosophical argument we can’t afford to make at the moment. Would it be better to do nothing that what is currently happening in and through mental health? Maybe (probably.) But that does not change the fact that people are forced into public mental health systems and services whether they want to be or not – sometimes literally against their will, sometimes due to structural oppression and economic injustice that leaves people feeling that there is little other choice.

Public mental health services aren’t just seeing a counselor – in fact if they were more that they might actually be better. Instead public mental health services are regularly tied to housing, physical health services, vocational support and the like, especially if and when an individual receives SSI/SSD.

So poor and marginalized individuals and families will continue to enter this system while we stand on the outside and complain about it and advocate for its elimination. I personally believe that it is better – no, in fact I believe it is absolutely critical that such person have allies and advocates on the INSIDE of a system that many people have no choice but to engage with.

It’s imperative that we have radicals on the outside, and it is imperative – possibly even more imperative that we have courageous subversive radicals on the insight fighting for and seeking to defend are human brothers and sisters while challenging the irrationality of the status quo thinking that keeps the system afloat.

Again, in my opinion, its never as simple as just “checking out” about the current public system as though millions of people aren’t impacted by it every single day. Just saying how much it should be done away with isn’t enough, and even taking direct action to see that happen isn’t enough. We need people behind “enemy lines” if you want to look at it that way, to try to help mend the wounds this system is creating, help people navigate through it and escape from it, and the like.

For me, the first time I partnered with a person stuck in secure psychiatric incarceration and gave him support and tips on how to beat his recommitment hearing (and when he beat it allow him to walk out of the front door of the facility a free man) was the first time I was confident we can’t just walk away from this broken machine – we have to try to be there for the people who are caught up in it.

Report comment

@ Andrew,

Well said.

Duane

Report comment

Andrew,

Please see clarification comment above (posted in wrong place).

Duane

Report comment

Thanks for your powerful articulation of purpose and radical revisioning, Andrew. The thing that is heartening to me is that this system is built on ideas and while it’s true that those ideas have become ossified in the form of billing codes and formal procedure and reinforced through the threat of professional liability, the core of it all is based – like anything in ideas. Yes, there are industrial pressures which hold the current workings in place and, yes, those pressures are very strong. However, at the core of any industry which purports to seek to care for people is a stated commitment to do no harm and the evidence – both anecdotal and empirical – is mounting that – in spite of whatever misguided intention these systems may be operating under, whatever assumption of “good work” they may use to justify actions that are harmful and negligent of human rights and human potential- that not only is harm being done, but it is costing billions of dollars. Incommensurability – in a Kuhnian sense, in which bad science eventually creates its own demise – is on our side. I think the challenge of people working within these systems is immense and power is a privilege. Even for me, a person who is relatively privileged herself, with the social capital of a smile full of teeth and a college degree and ways of speaking that are accessible and appealing to those who make decisions, well…my individual power to change anything is very limited.

…which is why it is necessary to find allies and to work together to forge a shared vision of change.

The barriers to efficacy and access are real and privilege bound beyond belief.

Thanks again for your thoughts and commitment to change. I have more to think about…

Report comment

I do have to make the caveat that I’m not sure I am as hopeful as you are, though I admire your optimism and feel like we are not at cross purposes.

Right now I tend to see participation in the system much more like we are Oskar Schindlers – not having hope that the machine will actually change its course, but committed to saving as many lives as we can.

(slightly flawed analogy, believe me I know I don’t “save” people, but I hope my meaning still comes through)

Report comment

Working to change the system from within is a noble goal and takes a lot of courage. I hope eventually those working from inside and those working from the outside will find themselves working together, because the will no longer be boundaries!

Report comment

I have a bee in my bonnet re: my assumption that the intention is to help. That’s not always the case. In a a lot of situations, the intention to keep a person “safe” or to keep other people “safe” from danger that presumed inherent in particular struggles, especially those associated with clinically identified psychosis. I’m not going to bother with the quotation marks here.

This motivation, that of keeping a person safe from a danger that is assumed, often comes at the cost of individual liberties and the goal is not to help a person, but to constrain them in their capacity to act – either by physical restraint or chemical restraint.

It is a difficult reality and I do have a chip on my shoulder.

It’s there for a reason though.

Report comment

Well, it’s fine by me if there are mental health professionals on the right side still working in the system. But Faith concedes that as a “peer” worker in the system, she has basically been told that she doesn’t have to work there if she doesn’t want to, meaning in fewer words, shut up or we will fire you.

Mental health professionals like Yana, having more credentials, of course have more leeway, plus her county mental “health” system is more liberal than most. But there is a limit beyond which she can’t go either.

(I should say here that I know both of these people personally.)

The problem I see about working from the inside, and these “dialogues”, which I am not against, is that they do nothing to change the beliefs that the general public has, about such things as “are schizophrenics really human?” which is one of the questions of the day in American culture, thanks to people like E. Fuller Torrey.

Keeping the discussions of these issues entirely within the tiny (and rather weird) world of the mental “health” system assures that nothing changes in the larger society.

And if the witch hunts and Nazi-like attacks on people with psychiatric labels continue the way they are, even people like Yana, with her fairly secure job, might find that being humane and kind to her clients might lead to being fired or worse.

If we don’t attend to changing the minds of the public, if we don’t get out of the little bubble of the mental “health” world, we are going to wake up and find a lot of us, especially survivors like me but kind mental “health” professionals too, in a grim situation.

Torrey is not a clown. Politicians and the media are listening to him. We all know what he wants, and he will get his way if we don’t fight back. We need to pay attention to the outside world.

Report comment

Hi Ted –

Thanks for saying hello here and for being a part of the strong voice of the psychiatric human rights movement in my mind.

As I see it, the goal of these dialogues is to engage the public…and whether or not that is the outcome has a lot to do with how they are organized.

We’re trying to approach this an opportunity to engage the public in these considerations and – given that this is a rather small city – we might have some success in initiating more public awareness of community-identified needs, concerns, and possible alternatives than some larger cities.

I actually edited out the part of the comment I made re: “employment is a choice” – as I had somewhat mis-framed it in a way that wasn’t entirely fair or accurate.

This statement was made to me when I was expressing the sense of ethical conflict I – as a person who opposes force and coercion -had in working for an organization that held a training on involuntary commitment procedures and the statement was made as if to say, “That is how things are right now and you don’t have to be here if the ethical conflict is too great for you to be comfortable with.”

Nobody said I would be fired, but chances are good that if I challenged policy and procedure too heartily, that I probably would lose my job…because organizational development is outside of the scope of my role as a peer and there are specific ways that one must go about changing policy and procedure.

Reality, reality, reality…it can be a frustrating thing to contend with.

“If we don’t attend to changing the minds of the public, if we don’t get out of the little bubble of the mental “health” world, we are going to wake up and find a lot of us, especially survivors like me but kind mental “health” professionals too, in a grim situation.”

That is a reality.

Thanks again for saying hi, and for reminding me of the reality of E Fuller Torrey. I guess now that NAMI has made gestures of distancing themselves from Torrey (e.g. having Whitaker speak at the national conference, rather than inviting Torrey), he’s moved on to courting popular media…which is frightening. The scary thing about Torrey and Jaffe is that they seem to actually have the privileged skills and knowledge (e.g. they can write a well-reference and formatted report) to impress upon people that they know what they are talking about…even if they don’t.

Report comment

Faith and All

As someone who has worked 20 years in community mental health as a therapist and as a huge critic of Biological Psychiatry, I would like to chime in a bit on these important questions.

Over the 20 years I have witnessed the gradual take over of these clinics by this oppressive model of treatment; it has been a painful and crazy making experience. This takeover so thoroughly dominates almost every aspect of how people are treated that it raises serious ethical questions of how to respond when working on the “inside.”

Yes, there are many dedicated people working in these clinics who are clearly helping many people. However, given the growing number of people treated by community mental health clinics who are put on psychiatric drugs (sometimes 7 or more prescriptions at one time) it has now reach a critical mass where one might make the serious argument that there is “more harm than good” taking place inside these clinics.

There desperately needs to be an organized movement of radical activists on the “outside” taking strong actions (targeted demonstrations and education exposing Biological Psychiatry) in order to shake the walls of the establishment and create more favorable conditions for radical change within. WITHOUT THIS MOVEMENT WE WILL REMAIN “VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS” WHO WILL BE COOPTED, MARGINALIZED, ISOLATED, ELIMINATED, OR PUSHED OVER THE EDGE INTO DEMORALIZATION OR INSANITY.

We need an approach of “walking on two legs”; where both the “inside” and “outside” work is both strengthening and complimenting the other; this makes it more difficult for the “powers that be” to push us to the margins or demoralize us into quitting. It’s much better “to burn out in battle” fighting for our principles than to “fade away.”

One example, I recently worked with a seasoned therapist (someone who works with those with the schizophrenic label) to present the Eleanor Longden video (The Voices in My Head) at a team meeting for our entire staff (30 therapist and 3 psychiatrists). This was combined with some print outs that challenge the medical model and the current standard of treatment involving so-called antipsychotic drugs. There was a spirited discussion that followed and very defensive reactions by one psychiatrist. We held our own and then some dealing with these hot topics. The staff found it stimulating and challenging. I was amazed how this seasoned therapist, whom I had thought was not a critical thinker and somewhat jaded over the years, enthusiastically took up this topic. She was quoting the Wunderlick study and speaking out strongly against the medical model.

I constantly pass out key articles criticizing Biological Psychiatry to people working in the clinic, including the doctors. Some doctors are receptive and actually share their dismay at the those prescribers engaged in the more obvious examples of poly-pharmacy at our agency.

This “inside” activism is not easy to do and I have had some conflicts with the administration on several occasions. I plan to increase this type of resistance on the “inside” which most definitely involves more risks of being fired. I have found that I cannot live with myself if I don’t dare to take these risks. The moral dilemmas working in these environments are very intense and are constantly in a state of flux. We need the support of other activists (in collectively organized groups) to be able to successfully negotiate these “uncharted waters.”

The stakes are high for the increasing number of victims of this system and for those working to make change within it. We all have much work to do. “Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win!” “There is no victory without risk.”

Richard

Report comment

Thanks everyone for sharing their experiences and the conflicts of working on the inside.

“We need the support of other activists (in collectively organized groups) to be able to successfully negotiate these “uncharted waters.””

What sorts of support would you want from activists on the outside? Can you give me a wish list?

I am focusing my efforts to work on the outside. I have the sort of personality that cannot tolerate working from the inside, so I would rather build bridges from the outside. I am currently trying to figure this thing out: where to invest my resources, energy, time, and money, to make a difference. It seems that successful coordination of activists inside and outside to system could be a winner.

Report comment

“I have the sort of personality that cannot tolerate working from the inside, so I would rather build bridges from the outside. I am currently trying to figure this thing out: where to invest my resources, energy, time, and money, to make a difference.”

I appreciate the direction of your thinking here, Tom – recognizing individual preference and strengths, and trying to figure out how to use those in working with others toward a common goal.

I have noticed in some activism movements there is this pressure to do things in a certain way, to stick to certain models of “what activism is” and very few opportunities are created for people to participate outside of those models. I am not saying that this tendency is always explicit – in people saying, “You have to do it this way if you want to be a part of things” – it’s more of an implicit message, “Like, here is what we are doing, if you want to help, you can do this part we’ve set up or that part we’ve set up…” rather than asking people, “What do you love to do? What interests you? Where is your passion in this? What are your strengths?” and spending time with people to help them find ways to contribute that are sustainable and meaningful for them.

I think you’re correct that a “successful coordination” from the inside and the outside is an effective strategy and that seems to be what is happening, though without a clear structure or an established strategy with agreed upon roles, etc.

Ted’s observation of the need for public engagement and raising awareness is spot-on. As for how that “looks” and might be best accomplished…well, there are endless conversations that have taken place on that matter and no clear conclusion has been drawn.

I have found value in Bill Moyers’ book Doing Democracy, which lays out some basic activism strategies highlighting the necessity of different approaches. It’s pretty basic, but definitely gives some insight into activism “roles” and ways for people with different strengths and interests to work together and also gives insight on why movements struggle and fall apart. It is a little entrenched in 20th century American models of activism, but so are many activists.

Thanks for responding and thinking in the direction of collaboration. I’ve developed into more of a hybrid activist myself, who really enjoys crossing lines and creatively pushing boundaries, trying to find human-to-human space between people.

I seriously have a dream of sitting down in dialogue with people like E Fuller Torrey, because it’s fascinating to me how worldviews are constructed and how we, as people, can be these earnest little kids who want to be the “good guys” and as we get older what that means just gets so distorted and disparate.

Of course, it might be tough to find human-to-human space with the likes of Torrey, since in his expressed worldview people with my psychiatric label and history are barely worthy of human consideration or respect, as we are seen as having limited capacity to “reason.”

Anyway, thanks…

Report comment

Richard, once again I see you as someone with the same goals and dreams as I have. Will you please contact me through MIA? I don’t want to post my email address here, because when I did that in the past, I got a lot of unwanted contacts.

I want to work with you on a project I am trying to start, one which I think will definitely interest you. Please get in touch.

Report comment

Thanks for sharing your experience and insight, Richard and for your tireless work in challenging bad ideas.

I’ve talked to people at the organization I work for about doing an in-house training on “alternative approaches to psychosis” – to create the opportunity for people to consider these states differently and to perhaps understand them in a different context. I have talked about meeting with the psychiatric service providers to discuss the role of psychiatric drugs in recovery education and to share recent research on the “atypical antipsychotics” and materials on shared informed decision making between prescribers and people who choose to use these drugs, and on ways to support people in exploring other ways to manage their difficult times and experiences.

…and they say, “Oh, yes, that’d be good…” – but, development of these opportunities takes time and support and the nurturing of a willingness to create spaces for staff to learn more about new developments in theory and ethical practice…and so it stalls, mostly because people are so busy keeping up with the day to day demands of working within the system that they are unable to make time for considerations of how things may be done differently.

I remember someone mentioning how helpful it would be if there were training materials made available to people on these subjects, constructed in a way that was accessible and appropriate for use within systems interested in providing recovery-oriented services.

That’d be extremely helpful, and would create consistency.

Most systems are not set up to have the capacity to meaningfully provide alternative supports. While there are plenty of valid arguments against peers, peer support (when in strong fidelity to the practice) does have the potential to be helpful. Of course, peer support and fidelity to the practice is a whole ‘nother can ‘o worms, a hundred other essays.

I appreciate your passion and perseverance in working within the system and also your recognition that support for people who attempt such work in a desire to be a catalyst for change is absolutely vital.

I am probably not going to be working in the system in the capacity of a peer for much longer…because, for someone who is intelligent and experienced and who has a strong sense of ethics, it is demoralizing and, to be frank, depressing.

I have only stayed so long as I have because I know that if I were not there, the people who come the center where I work that struggle with profound alienation, voices, paranoia, and all the trappings of years of being treated with neuroleptics…well, they’d have nobody to talk with about the messages they feel they receive, nobody to talk with about ways to “move through” difficult extreme states, nobody to share the reality of their experiences with…and thinking about them I want to stay, because to other practitioners these experiences are just the detritus of a severe and persistent mental illness and people see psychiatric drugs or a referral to an ACTT as the only way to respond…and yet I know that is not true.

However, the amount of good I am able to do in a part-time position, spending an hour a week with people, is limited and so…and so…and so…

That’s why I want to figure out how to finish this degree and get another one, find ways to support entire organizations in making alternative responses to psychosis and extreme states available.

Not only is it amazing to see the healing potential of simply being heard and having the power and struggle of one’s experiences affirmed, but compassionate and dialogic approaches may cost less and have better outcomes.

I am glad there is more and more research emerging that supports this fact.

Eventually, the agencies that structure policy and practice protocols (ahem, SAMHSA) are going to have to take a strong stance in making these approaches available.

I don’t understand why they wouldn’t. Yeah, there is plenty of pressure to adhere to the biopsychiatric paradigm – economic pressures, incentives – but, damn, why aren’t people more hopeful, more inspired, more excited that we seem to be at the edge of untangling what madness is and what it is not and, finally, what may truly help people = connection, empowerment, trauma healing, strategies to understand and navigate personal sensitivities and self/world conflicts with agreed upon reality, self-determination…

There is so much potential.

I don’t understand why people are content to accept the hopeless miasma of the simplistic biopsychiatric model and why they aren’t enthusiastically promoting the support and expansion of alternatives.

I guess that’s my naivete again…

Thanks again, Richard. Hope you enjoy the day…

Report comment

I think with the media Tom Insel/NIMH questioning long term use of drugs and the dsm5 ( not that I believe for one moment that he is an ally to the human rights movement) it has worked to our advantage to speak up more from the inside, at this stage in my career I’m more willing to say ” let them fire me” for speaking my truth …

I was inspired by Faiths blog here initially as it resonated to create more community dialogue, I liked the sound of “talking over fences”. I think this might be how we move forward is finding connections with ” the other side”‘places o f dissatisfaction with the system that are shared. One example might be Family members, who have had a strong voice, they aren’t happy with the system either and many hate seeing their loved ones handcuffed by police. And put in seclusion rooms and medicated, Now many are at a loss as NAMI is hearing the criticism of the medical model and I’m sure is at a cross roads ….just one example…many are seeking answers. Of course most want medical answers, but meanwhile there aren’t any, I just believe there’s opportunity in having these dialogues in our communities to begin reshaping systems. It’s so true what Richard Lewis says, that the recipients of these public services are often the most vulnerable and poverty doesn’t create choices to allow people to go to “alternative healers” so it’s the public community mh clinics that need to better respond to the human experience in a humane manner

Report comment

Great discussion! There is definitely a place for both “outside” and “inside” movements, and both are vital to success. We need people with credentials and insider credibility to challenge the dominant paradigm, and we need tons of active survivors telling their stories and demanding change. And we need writers like Bob and many others laying out the science and the sociology and the economics of change.

What I think is MOST needed is to create a system where getting people more capable and independent and empowered is the goal, and where the incentives encourage instead of discouraging this. That won’t happen without some “system change” work from the inside. It will be slow, it will be awkward, it will never look exactly like we want it to, but change does happen, even in giant bureaucracies, if there is enough weight to overcome the internal momentum. Meanwhile, we keep educating, one person at a time, and each of us uses our weight and expertise where it can help the most. There is no magic – we just have to keep pushing and not give up until it’s done!

—- Steve

Report comment

!!!!!!!!!!! http://mobile.nytimes.com/2013/10/22/world/americas/ex-patients-police-mexicos-mental-health-system.html

Report comment

…now that’s inspiring.

Report comment

I hope you’ve seen my posts on the Kansas City Dialogues? Send me an email and I’ll get you as much info as possible.

Report comment

I have, Corinna! I actually almost commented to say hi and let you know what was going on here…but, instead I just thought about things.

I actually think it was the email blast from Wellness Wordworks that really helped me to know that it was important that c/s/x folks get actively involved in the organizing of these dialogues from day one.

It’s interesting, because as an organizer (and researcher, since I am working on doing my MA project on this process and its outcomes), I can’t really have an agenda other than creating space for dialogue – though there have been a couple of alternatives-oriented dialogues held nationally under the auspices of Creating Community Solutions. I think one in Portland was called Rethinking Psychiatry.

Anyway, yes! I will send you an email and definitely look forward to hearing from you on your experience with the dialogues initiative in KC.

Thanks for saying hi and sorry I didn’t comment on your pieces re: participation in the dialogues. I just haven’t been too comment-y lately…I mostly just read things and then think about them.

Like I said though, your efforts out there definitely contributed to the vision here…

Report comment

Hey, Corinna – Sorry if in the auto-email notification of the above post your name was spelled incorrectly.

I tend to think that it is 2 r’s, rather than 2 n’s and so I mess it up. Now that I have made this statement, I will never bungle the spelling again.

Report comment

Thought provoking reading….inside the system, outside…we just have to find whats right for us personally.. given our own dispositions imo…too much infighting about “what is right” …I think that it’s common trait of powerless groups…

Sharing for interest…. http://studymore.org.uk/mpu.htm A UK history..

Report comment

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Opal

Before even Ted’s time…

Report comment