Email from Fiona Godlee, Editor of the British Medical Journal (BMJ) to Restoring Invisible and Abandoned Trials (RIAT), July 6th 2015

Re: Study 329

Dear Dr Jureidini,

Many thanks for your letter. I quite understand your concerns. You are right to say that there are few or no precedents against which to compare this article. We ourselves are feeling our way, both with the RIAT process since this is the first full RIAT research paper we will publish, and with the specific challenges posed by this particular study and you as the paper’s authors. I want to stress that we are proceeding in good faith with the clear aim of publishing the article as soon as possible provided we can do so safely. …

All best wishes

Fiona Godlee FRCP

Editor-in-Chief The BMJ

The Path to Publication

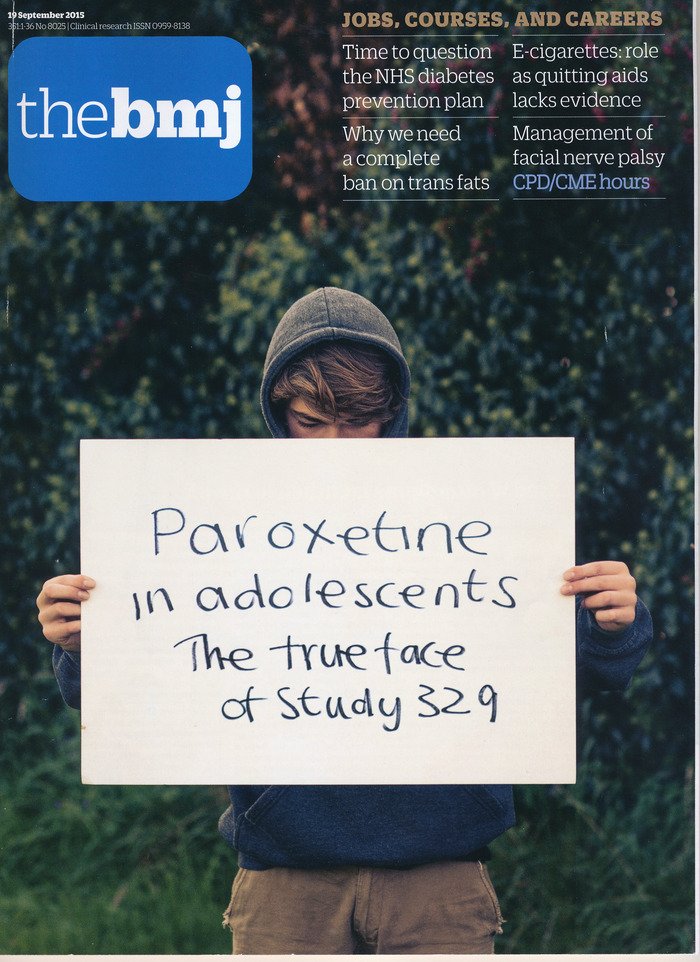

The BMJ states that it takes on average eight weeks from submission of an article to publication. The review process for Restoring Study 329 took a year, with a three-month review process involving six reviewers to begin with, and then a further four reviews in a four-month process, leading to a provisional acceptance in March that was withdrawn.

Ultimately there were seven versions of the article. All versions and all reviews and responses are available on Restoring Study 329 (See Study329.org – timeline to publication).

At the time of this email from Fiona Godlee it was far from clear that the BMJ were committed to publishing the paper.

Conflicting Interests

The Lancet and BMJ were among the earliest medical journals. They began in Britain in the early nineteenth century with a public health brief.

Public Health began in an effort to contain contagious diseases. No one knew what lay behind epidemics of plague, smallpox, cholera and typhus. The problem might lie in abattoirs that sat in the middle of towns in those days, or in the unhealthy constitutions of those who became ill. A lot of powerful interests were at stake.

In the absence of effective treatments, the public health movement stimulated a revolution by focusing on the environment and changes to it rather than on the individual. Removing the handle on the Broad Street pump offered a wonderful symbol of its mission to prevent disease rather than intervening to treat when it it was often too late.

While there might be nervous abattoir owners on one side, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, public health science and politics and business were largely on the same side. The new science created opportunities for new research-based businesses. Establishing that bacteria caused infections opened up the prospect of vaccines and antibiotics and helped the growth of the insurance industry. The wealth that came with these new industries lifted many out of poverty and in this way helped health just as much as hygiene helped by preventing diseases.

The conflicts of interest at that point lay, as they had done since Galileo, between science and religious or political beliefs – between the evidence that vaccination helped and those who for religious or political reasons were opposed to vaccination or to people being forced to take vaccinations.

Twentieth Century Conflicts

With the development of bacteriology and the demonstration that bugs caused infections and the hunt for a Magic Bullet, the focus drifted back from preventing disorders to treating individuals. This environment is fine if you take your pills – antibiotics, antidepressants, statins — whatever.

This development was linked to another; Because the development of modern science was so interlinked with the development of modern industry, industry was among the earliest to embrace “research.” Long before the Cochrane Collaboration began systematic reviews, the lead industry was systematically collecting all articles in the lay or scientific press about the effects of lead, in order to monitor the threat to their business and to be able to assess what lead blood levels might “wash” with the public and politicians. The industry also supported scientists in research projects to minimize problems. But minimization of problems did not mean doing studies to determine the lowest blood lead level at which biological effects became apparent. It meant studies that would minimize problems to industry.

Lead is not on the radar these days for people in the way it once was, or in the way that it and other heavy metal poisonings probably still should be. The epidemiology of schizophrenia, for instance shows an initial emergence of this disease in the nineteenth century, and a more recent decline, and this rise and fall parallels lead usage and lead levels. Dementia and a range of other diseases like cancer likely stem from environmental sources that have a basis in industrial pollution.

In part because the tobacco industry’s famous aphorism Doubt is our Product crystallized a modus operandi for all modern corporations, there is some awareness today that an increasing amount of “scientific” research is done to muddy the waters on questions of environmentally induced diseases. This is a use of data against Science; a generation of the Appearance of Science.

Dwight Eisenhower, in a famous address in 1961 just before he left presidential office, caught some features of this new world:

“In holding scientific research & discovery in respect as we should, we must be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could become the captive of a scientific and technological elite.”

Female Genital Mutilation

The situation we now have is something like as follows: You want to submit an article to our Journal on the benefits of Female Genital Mutilation? You must declare your “conflict” and we might decide not to publish no matter how good your data looks because this looks like data marshaled in support of a belief system rather than science proper.

This example is not all that far-fetched. Many books and articles routinely carry claims about the supposed results of studies demonstrating the health benefits of circumcision (MGM), about which all men have a conflict.

Whatever anyone’s beliefs about FGM and MGM, at the end of the day the power of science lies in an acceptance that we resolve issues with data. The idea that pharmaceutical companies can hang onto data by Force Majeure is the antithesis of science.

The new biology, pharmacology and trials-ology risks undoing Galileo and putting the individual back at the center of the universe. We can’t randomize environments but we can randomize individuals and if some drug produces a difference in a situation the simplest and most profitable conclusion will usually be that we have corrected a defect in the individual.

The new biology, pharmacology and trials-ology risks undoing the Bible even. The script is being rewritten to tell the story of a vulnerable Goliath, who while laboring away at making the medicines critical to all of us, and providing jobs, is at increasing risk from an unscrupulous and unethical David.

While there is the occasional headline such as a former editor of the BMJ resigning an honorary post from Nottingham University because it took money from the tobacco industry, the new rules of the game are as outlined by Fiona Godlee – anyone who has attempted on the basis of data to challenge a pharmaceutical company about the adverse effects their drugs cause must ipso facto be deemed to have a Conflict of Interest on a par with someone presenting data apparently showing health benefits from FGM.

The BMJ and NEJM reserve the right not to publish material like this, on the basis that while we are committed to resolving issues on the basis of data, anyone who has accessed data on this issue or in this fashion clearly has some strange belief system and must be deemed to be suspect – unlike companies like Pfizer whose actions are assumed, apparently, to follow the data in a disinterested fashion.

Medication Time

What’s really going on is that journals are scared of industry. This is partly because the leading figures in medicine have become minions concerned more for the health of industry than the health of people and there is no-one who is likely to back up a journal willing to take a tough stand.

There is another reason. While data might really be new data – previously unavailable – the BMJ are scared that if they feature it they will be put out of business. Journals are a business that feeds on science, rather than part of science.

These journals are caught in a 1960s-style double bind. They are dealing with a Nurse Ratchet, who writes friendly letters on first-name terms to the journal’s Editor – Dear Fiona – but who has made it clear she will sue and put them out of business if they don’t play ball at medication time.

Close to the last thing a journal is willing to do today is feature any article about the biggest public health issue of our day – the biggest source of environmental toxicity – the morbidity and mortality caused by treatment.

In the face of a complex situation like this, the temptation — as Daniel Kahneman told us 40 years ago — is to resort to the Fundamental Attributional Error, which is, essentially, to look for who to blame. But rather than blame the powers that might house-arrest them (as happened to Galileo), the BMJ, along with society’s new religious authorities, locate the problem in Galileo – the person attempting to produce the data.

In the case of Study 329 there also appeared to be a desperate hunt for some box to tick that would make BMJ fireproof, some proof that the scurvy knaves behind the Restoration of Study 329 were adhering to some protocol that would make the results objective and definitive – exactly the opposite message to the message of the final article, which is that the results are provisional and that objectivity as regards what these drugs do — for good and for bad — arises from having the data out there so they can be contested.

Science involves getting data into the public domain where it can challenge beliefs. But decades ago BMJ and other journals gave up on any attempt to access the clinical trial data behind the claims being made.

Now the BMJ is signed up to an AllTrials coalition that includes GSK, and is against Data Access.

So I guess we can’t use science any longer since us humans all have an inherent conflict of interest?? Did I get it?

Report comment

You don’t want to buy ineffective and toxic meds for huge amouts of money? Clear conflict of interest.

In the world where corporations have constitutional rights nothing is too crazy.

Report comment

Thank you for pushing back against the pseudoscience that supports the medical model. the blatant anti-science of the research of pharmaceutical companies attests to the power of money to corrupt science.

Best wishes, Steve

Report comment