In part one of my reflections on the two thinking designs, namely the “scientific” “objective realism paradigm” and the “relational perspective paradigm” I pointed out that we exist, think, and practice in both “worldviews” and, consequently, have to understand when one or the other is more appropriate for use in making sense of our world. We are more familiar with the former paradigm, which serves as the principal design of our thinking in regard to our not always consciously reflected, “naïve” worldview. It is prevalent in scientific discourse, medical achievements, and technological advances. In general, our day-to-day exposure to and manipulation of the mainly material object world around us reveals the dominant function of this paradigm.

I will focus here, however, primarily on the “relational perspective paradigm” in order to buttress the radical, i.e. second order change connected with adopting this thinking frame in clinical practice as the guiding orientation for our thinking and practicing as people and as clinicians. At the Center for Family, Community & Social Justice, Inc. we have made every effort to implement a “Just Therapy Practice” that reflects the decision to serve children, adolescents and their families and communities in oppressed urban areas according to principles underlying the “relational perspective paradigm.”

The fact of having to make a choice at all of which paradigm to adopt at any given moment as the primarily and explicitly guiding one, is unsettling to us, because this choice catapults us out of our accustomed way of seeing the material world and the human world as a fixed objective reality and feeling at home in it. Applying this “new” paradigm we experience ourselves questioning the dualistic “objective realism paradigm” that reliably seemed to deliver the reality we could accept as the truth about the human, social, and material environment we are living in. We experience ourselves as strangers in a once familiar land, driven out of our thinking home, because old truths that seemed self-evident to us, lost their predictive and reliable validity. It takes some time for us to appreciate that the adoption of a design of thinking oriented by a relational and contextual perspective also opens new vistas and perspectives for personal and professional encounters and work.

1. New Relational and Contextual Realities made Recognizable by the “Relational Perspective Paradigm”

With the perspectives shaped by the “relational perspective paradigm” the incredibly diverse and complex relational networks in which therapist and client are involved come into sharp focus.

- With adopting this paradigm we have the eyes and ears able to focus on the relationships among health professionals (organization, practice, research group) in a professional setting; on the family of origin of the therapist; and her/his professional and family ancestors. In other words, we begin to build an increasing understanding of the therapist’s “social and relational location”. Obviously, this cognizance of the relational and contextual world of the professional is of great importance as anybody will realize who walks into a doctor’s office or who had been part of a surgical team or who experienced clinical round tables with often heated discussions. The clinical “reality” that is part of the conversation is socially constructed by all participants.

- Equally, guided by the relational perspective mindset the relationship between the health professional(s) and the other(s), i.e. “client(s)” takes center stage. This is the relationship that drives the healing process forward. In the view of the “relational perspective paradigm” there is a circular relational process, i.e. a process of change and healing that involves all who are part of it, therapist(s) and client(s)! People, often desperate, traumatized, and vulnerable, who consult with a therapist will not engage in the therapeutic relationship and open themselves up unless they have the sense that the helping professional – to whatever degree – will enter into a (professional) relationship with them that will also affect the professional. From the point of view of the “relational perspective paradigm” both therapist and client(s) render themselves vulnerable to each other and unguarded for surprises. They become receptive to a process that leads to transformation.

- Whether working with individuals, couples or families, with the “relational perspective paradigm” in mind professionals discover the multiple relational networks, notably family systems, and wider personal networks in which individuals are embedded while at the same token they are part of an even broader community with numerous socially crucial webs. Just as it would be foolish to discard the complex interrelationships between cells in the human body and take only individual cells for real, so it is not enough to presume only individuals count and to overlook the fact that they are embedded in an incredibly varied and rich complexity of human interrelationships within the wider social world.

- Our “relational perspective” mind frame does not stop here. We discover also the relationship (our own and the others’) with people from the past. Here we include the entire historical dimension of individuals and families in its impact on the present (for example, enslavement or extinction and immigration history) and unearth the context of family memories and legacies, including remembering ancestors who had specific importance for family members living now. In clinical encounters we construct a family genogram or listen to family survival, oppression, and resilience narratives.

- Finally, in the “relational perspective realism” we own our responsibility for future generations and are mindful creating positive legacies and missions into the future that will sustain the people coming after us. Ultimately, we honor our responsibility and concern for the survival of planet Earth.

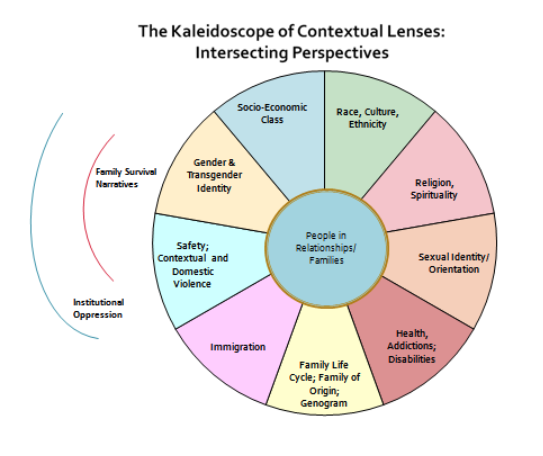

The focus of the “relational perspective paradigm” is also on socially constructed human environments and contexts, the latter signifying the broadest lens that can capture societal realities such as socio-economic status, condition of neighborhoods, culture, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, the effects of war or current forms of institutional, especially racist oppression. At the Center we speak of a relationship- and context-centered perspective. While relationship signifies a more intimate and personal connection with the other(s), the context of a person or family connects all the different aspects of a given environment, especially social aspects that have their own boundaries, but also intersect with each other.

The “Kaleidoscope of Contextual Lenses” – an example from clinical practice

In order to make particularly the broader social context visible the Center for Family, Community, and Social Justice has developed a set of contextual perspectives which, much like photographic lenses, help the Center therapists to focus on the relational and contextual world of couples, families, and individuals. We use the insights derived from these perspectives as orientations for clinical practice. Applying the “relational perspective paradigm’s” axioms, “how you look determines what you see” and “how you listen determines what you hear”, these perspectives and corresponding narratives can guide therapists’ way of looking and listening. These mind orienting guides help clinicians to perceive the most relevant aspects of people’s and families’ contexts. In addition, these contextual perspectives intersect with each other in multiple ways and highlight reality aspects of clients’ and families that otherwise would have remained invisible.

2. The Social Justice Perspective – A challenge to Psychotherapy

As we are looking and listening aided by the Kaleidoscope the features, patterns, characteristics and narratives of a person’s relationships and social environment are brought sharply into focus. We are able to recognize in this process many of the societal forces frozen into rigid structures of oppression, domination, and institutionalized injustice. These forces become sources of suffering, pain, and trauma for many people. In other words, as professional helpers we are not able to avoid the question of justice in clinical systemic psychotherapy any longer.

Considering the more intimate and personal characteristics of the relational connection with each other first, clients and therapists can practice relational justice between each other by emphasizing relational aspects that are critically important as the basis of psychotherapy, guided by the “relational perspective paradigm”.

A number of aspects of “just practice” on the most basic relational level come to mind:

- Therapist and client may allow themselves to be drawn into the face-to-face character of the clinical process, an encounter that envelopes both the therapist and the other into an interactional dynamic that creates a relationship prior to any cognitive understanding, let alone “diagnosing” the other. Before any professional vs. client dynamic both (or all involved) encounter each other as human beings, as people who share the “same” humanity with each other.

- This relational process is asymmetric, i.e. the other occupies the center of the process. The other (client) is calling me (the therapist); who I am is put in question. I am responding to the other; my existence at this moment is there for the other(s), and revolves around her or his or a family’s experiences, questions, dilemmas. Their expertise about their life is privileged over my (professional) knowledge or academic credentials. Justice here is unequal, asymmetric, because the other and her/his vulnerability are at the center as we face each other – before our designation as professional and client.

- The most basic encounter of two (or more) people face to face also implies the deconstruction of all professional hierarchies, of expert power, and of the rules of the dominant discourse (including the DSM!): We, the experts, become ourselves vulnerable, have to tolerate being taught by the other(s), have to collaborate in the process of healing with humility and curiosity, have to employ a language of caring, inviting and connecting with the other(s).

- The relational process between therapist and client is therefore understood here as a source of emerging relational justice and empowerment, revitalizing strengths and resilience of the other(s). As this conceptualization is applied to the web of intimate personal relationships in marriages, long term relationships, and families it helps to unearth and visualize relational injustices, biases and discriminations, but also inherent and unappreciated resources and personal and relational assets.

Having established a relational connection with each other, therapist and client(s) turn together “looking outward” and begin the work of transformation of an individual, a couple, a family by addressing the contextual injustice factors impacting people’s lives.

- In disadvantaged neighborhoods they may look for and listen to stories about poverty and paucity of jobs, violence in the neighborhood, racism and constant micro-aggressions, gender inequality and discrimination, homophobia, isolation and lack of community, but also for indicators of institutionalized injustice, such as lack of accessible social services and other resources, homelessness, failing or neglected schools, insufficient housing, gang presence, lack of public support for families, etc.

- Being curious and paying focused attention therapists and clients hear about traumatic personal and community events in the past with accompanying narratives of despair and survival. They may often discover contextual factors impacting people’s lives with overwhelming force for years such as incidents of physical and sexual violence, a history of enslavement and exploitation during the process of immigration (incl. non-documented status), malnutrition during early childhood, victimization within the health and mental health systems, maltreatment by the educational system, early prison experiences with its devastating impact on families, etc.

- Given the paucity of rehabilitation centers and hospitals drug and alcohol addiction and the label “mentally ill” become obvious as major sources of victimization, stigmatization, self-destruction, and, often, long-term and torturous imprisonment – all with tremendous impact on entire families and neighborhoods.

- Keeping a high level of complexity in accordance with their relationally and contextually oriented mind therapists relate on a very basic human level, apply all the skills of their expertise, and support the growing resilience of clients and families to transform themselves and their human, social, and material environment.

3. Social Justice as a “Meta-Perspective” in the Relational Perspective Paradigm

Structures of Injustice Surfacing in People’s Stories

Contextual injustices in our society’s history and structure are experienced daily and are significant factors in human suffering, psychic pain, disturbing and disturbed behaviors and physical illness. The separation of psychological inside and social outside is an artificial construct intended to make us overlook the power of these unjust societal, racist, and economic structures that contribute to emotional pain and despair.

The others (“clients”) whom therapists encounter experience personal and interpersonal issues that do not arise from their biological, psychological, and social development or from their family dynamics in isolation. To “diagnose” an individual without exploring context, therefore, i.e. without inquiring intensively about this person’s intimate relational network and about his or her significant contexts constitutes by itself an act of injustice.

Particularly people in neglected urban environments are exposed to many stressors and injuries that are rooted in our society’s or this particular city’s structural injustices. Using the “Kaleidoscope of Contextual Perspectives” the power of the intersection of the various factors becomes very clear. Economic exploitation and the growing disparity of wealth between rich and poor; rigid walls between social classes; lifelong status as marginalized within the dominant white culture; poverty and violence in the neighborhoods; continuing racism, evident in the administration of justice and in daily micro-aggressions; disparities in health care and social services delivery; hardships due to the imprisonment of family members; discrimination against women, children, gays, lesbians, or transgendered people, – in general, the likely mistreatment of anyone who is different according to the norms of the dominant elite can’t be overlooked. The social justice meta-perspective, therefore, has to be integral to the therapeutic inquiry and understanding of children, adolescents, adults and families.

Social justice as a meta-perspective guiding therapeutic encounters may seem obvious to therapists who are working in contexts of deprivation and widespread social neglect. Adopting a “relational perspective paradigm”, however, we discover similar, although perhaps less blatant, relational and contextual injustices also in conversations with individuals, couples, or families with a middle class status and from an economically more stable background. The mixture of intersecting perspectives highlighting a White, African-American, Hispanic or Asian middle class family’s “reality edit” may be different, they most likely struggle with issues of injustice and societal oppression also. Again: How you look and inquire determines what you see and discover!

4. Examples of Social Justice Work in “Just Clinical Practice”

Social justice as a “meta-perspective” orienting the therapeutic process and guiding clinical practice transforms and enriches both therapists and clients. Some important steps of “justice work” are listed here.

Witnessing Stories and Public Remembrance

Families tell stories, often in a language reflecting their ethnic heritage and culture that they try to preserve. They talk about present or past traumatic incidents or about long smoldering conflicts and irreconcilable relational traps, or about their journeys replete with danger as they were forced to immigrate to this country to survive. Therapists become eye and ear witnesses asking questions, encouraging other family members to join in the narrations or broadening the generational context so people can listen to the voices of previous generations. In the relative safety of a family session incidences of physical or sexual abuse, tales of deprivation and general affliction, times of despair or helpless rage, of mental confusion and bewilderment, or long standing family disagreements can surface and be heard.

Remembering and acknowledging the struggles, sufferings, and injustices family members had experienced in previous generations in the public sphere of the family conversation is healing and strengthening for all. It is a form of restoring justice to those whose life and death made the family’s life better.

The Work of Reconciliation

Therapists and friends from the community can pursue actively the goal of reconnecting fragmented personal relational networks, of reconciling hostile family members and of assisting them to rebuild the relationship with each other. This process requires a sense for justice and for balance of opposing forces, cultural empathy and humility, attentiveness to time, and “multi-partiality”, i.e. the ability to do justice to each person’s perspective.

Again, the work of reconciliation includes the therapists, particularly white therapists, who see people of color in treatment and begin a process of transformation as they listen to their clients’ and families’ narratives about oppression and almost daily micro-aggressions. Invariably, the face to face encounter of therapist and clients has to lead to a deconstruction of the white supremacist attitude (whether conscious or not) and to a level of racial reconciliation and human relating that will make the therapeutic process possible in the first place. In addition, white therapists and therapists of color would have to learn to make the Whiteness of white clients explicit as part of their justice related work.

Justice work in the Family’s Social Environment

Beyond the family’s immediate context therapists may decide to see it as a legitimate task to support all efforts to transform and restore societal, racial, and gender specific justice in neighborhoods where civic and community life has suffered. Families are encouraged to not give up advocating for justice. Such relationship and context-centered therapy can provide the groundwork to motivate families to take initiative in their neighborhood or in their children’s school and advocate for change and address issues of justice on many levels.

For professionals with an epistemological orientation that is emphasizing the relational and contextual perspectives it will be obvious that any group activity in the community supporting individuals and families with “mental health or behavioral issues” should be welcomed. Similarly, the professional community should support fighting against the stigma of having a psychiatric label or, broader, against social injustice in the “mental health” field in general.

The challenge seems to me to bring professionals, members of the community, and self-help groups together in support of those who suffered discrimination and maltreatment within the “mental health system,” including over-prescription of psychiatric drugs.

“The challenge seems to me to bring professionals, members of the community, and self-help groups together in support of those who suffered discrimination and maltreatment within the “mental health system,” including over-prescription of psychiatric drugs.”

Yes, I agree. I’ve found that those that place themselves around people who have gone through this have a hard time being humble—and even respectful—to the personal expertise of those who have the lived experienced. The projections, conjectures, stigma and discrimination just go on and on and on, layer after layer, generation after generation.

I believe it’s a matter of those who have been through this particular dark night of the soul to assert themselves and trust their information, in the face of resistance from those around them. That’s healing, and changing the system. Courage, fortitude, and self-insight are exactly what are gained when one takes the journey, that’s the whole point.

As it turns out, I’m now supporting others and their families, having transformed my own family system thanks to the healing work I did. It’s amazing the effect that simple truth-speaking can have on a family culture and dynamic. So I found justice, after all.

Thank you for your meaningful words of validation and recognition, on behalf of psychiatric survivors (well, on behalf of this one, at least, can’t speak for others).

Report comment

My experience with psychiatric practitioners is they do basically the opposite of what you claim you’re planning to do. And my further research has enlightened me to the reality that the psychiatric field, as a whole, is basically as incompetent and delusional, or brainwashed, as my practitioners were.

My practitioners were staggeringly bad listeners, and they incessantly denied the abuse of my child. So much so, that once my family’s medical records were finally handed over by some decent nurses, including the medical evidence of the abuse of my child in his medical records, and proof my psychiatrist hadn’t actually accurately heard anything I said. And I confronted him with all his written “delusions,” and the fact I now had medical evidence of the child abuse, my psychiatrist literally wrote into his medical records that my life was “a credible fictional story.” He tried to convince my husband I needed to be reargued, and he wanted my child drugged. Talk about a person with less than zero empathy.

“Just as it would be foolish to discard the complex interrelationships between cells in the human body and take only individual cells for real, so it is not enough to presume only individuals count and to overlook the fact that they are embedded in an incredibly varied and rich complexity of human interrelationships within the wider social world.”

I absolutely agree with this statement, but did not realize when I went to psychiatric practitioners for help, due to some prior iatrogenesis, and for assistance in overcoming my denial of the abuse of my child. That all psychiatric practitioners today apparently do “presume only individuals count [although they actually discount their patient’s views] and … overlook the fact that they are embedded in an incredibly varied and rich complexity of human interrelationships within the wider social world.” I have never, in my entire life, met people who harbored such a myopic belief system, as today’s psychiatric practitioners.

Thus, I’m quite certain you are grossly overestimating the abilities of those in the psychiatric and psychological professions. They would need to have their entire worldview changed in order to function in the manner you describe. And it’d be easier to get normal people, who are not deluded by belief in the DSM disorders, than to retrain the current “professionals.”

I will add one more comment. As a Christian, I was raised to believe in the “seen and unseen.” Today’s psychiatrists only believe in the “seen,” and declare everything in the “unseen” category to be “delusional” or “fictional.” Number one, this psychiatric habit is technically illegal, at least when it comes to their claiming faith in God or the Holy Spirit to be a “delusion” or “voice,” as my practitioners did. But more than that, the quantum physicists are finding this to be the true nature of reality. So today’s psychiatric belief system really has nothing to do with science, legal behavior, nor does it have any respect for the wisdom of the ages.

Good luck with your endeavor, however, I believe the current psychiatrists created exactly the system they desired, and to try and retrain these completely unethical, un-empathic, money worshippers to actually care and treat others with mutual respect is a waste of time. We just got the wrong people into today’s psychiatric industry. If such an industry is needed, and I don’t know that it is, since I believe it creates more injustice, than it provides care. I’m quite certain it would make more sense employ actually caring, empathic, good hearted people in the industry, instead of trying to change the views and nature of the current “professionals.”

Report comment

Pardon the typos, re-drugged, not “reargued.” And “I’m quite certain it would make more sense to employ actually caring, empathic, good hearted people in the industry, instead of trying to change the views and nature of the current ‘professionals.'”

Report comment

Hi, Alex and Someone Else,

Your comments reminded me again how much interpersonal and social trauma and pain is hidden underneath the phenomena called “mental illnesses” by the “industry” constructed by bio-psychiatry and pharmaceutical corporations. Thank you for letting some of your personal history shine through.

I am more and more convinced that, first, the people who have survived the traumata leading to “psychiatric symptoms” need to talk to others with similar experiences, form groups and advocate for each other, as you do. That is healing. If people from the therapeutic professions are willing to join, not as professionals, but as people who also went through suffering, they should be welcome.

A second step could and should be to open our minds/hearts for people around us who have experienced pain and injustice (often over generations) on account of their race, gender, diversity, sexual identity, unsurmountable poverty etc. etc. “Psychiatric Survivors” are only one group of oppressed people in our society. Popular outrage, active advocacy, and joining hands with and for the others will help these others to change their conditions and will deepen and broaden our humanity.

It’s good to reflect on these matters on M.L. King’s day.

Report comment