Psychosis is associated with several forms of adversity, deprivation, and with living in urban areas. New work drawing on UK Biobank data investigates whether psychosis is part of a ‘syndemic’ of multiple adversities. The findings stress the importance of interactions between childhood and present adversities in preventive and therapeutic interventions for psychotic disorders, especially among ethnic minorities, as lifetime adversity and current adversity were more strongly associated among ethnic minorities than white British people.

People from lower socioeconomic and ethnic minority backgrounds typically experience a higher number of negative life events, more ‘generic life stressors’ of modern life (e.g., occupational financial, relational), and more significant psychological distress. Racism and minority stress have been linked to poor mental health outcomes such as depression and were found to be a clear contributor to youth mental health challenges. A 2016 study published in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology found that discrimination based on minority status may precede the emergence of psychosis. The authors write:

“Some evidence suggests that psychological distress stems from comparatively limited access to resources for coping, whether socioeconomic, intrapersonal, interpersonal or more place-based factors … that might buffer the effects of deprivation.”

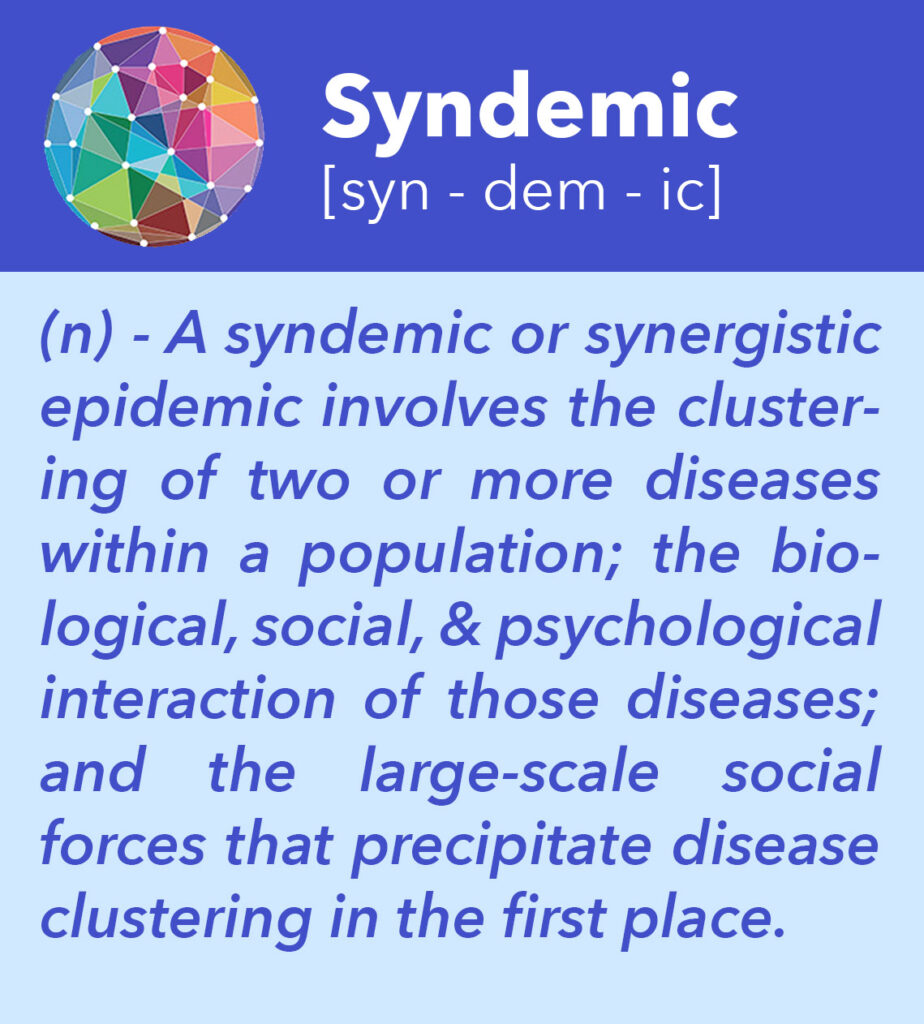

The authors conjecture that the disproportionate exposure to stressors, adversity, and trauma may explain the higher incidence of psychosis in ethnic minorities. Yet little research has investigated the mechanisms by which adversity, discrimination, and racism lead to poor health outcomes. Emerging research on ‘syndemics’ offers a conceptual framework to link diverse influences on mental and physical health outcomes, including racism and ethnic discrimination.

The authors conjecture that the disproportionate exposure to stressors, adversity, and trauma may explain the higher incidence of psychosis in ethnic minorities. Yet little research has investigated the mechanisms by which adversity, discrimination, and racism lead to poor health outcomes. Emerging research on ‘syndemics’ offers a conceptual framework to link diverse influences on mental and physical health outcomes, including racism and ethnic discrimination.

A syndemic or synergistic epidemic is the aggregation of two or more concurrent or sequential epidemics or disease clusters in a population with biological interactions, which exacerbate the prognosis and burden of disease. Merrill Singer developed the term in 1996 to outline related epidemics that cluster in places and people, with the interaction of adverse socio-environmental contexts and risks. The authors propose that a deeper understanding of complex social, health, racial and spatial factors that drive health inequalities may best be understood through a ‘syndemic’ lens.

This research study utilizes this lens to study the high risk of psychosis for ethnic minorities in Britain. The authors used data from Biobank UK, an ongoing cohort that collects information about a range of background and health-related variables among more than 500,000 participants recruited between 2006 and 2010. The Biobank assesses participants through self-reports of items covering childhood adverse experiences, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and war experiences. Using this data, the researchers used a logistic regression model to test the statistical associations of different variables with psychosis.

The study revealed moderate associations between lifetime adversity and current adversity and between current adversity and biomarkers. Significantly, all three of these constructs showed statistical associations with psychosis, with lifetime adversity and current adversity most strongly associated among ethnic minorities. This has important implications for public health policies, which tend to focus on single outcomes and only certain diseases modeled as epidemics, downplaying the synergistic effects of aggregated risk factors. Regarding public health prevention of psychosis, the authors conclude:

“The findings suggest that clinical interventions will need to recognize the social and structural drivers of psychosis and that past and ongoing adversity should be a target for both public health prevention efforts and therapies that recognize this complexity.

Thus, syndemic policies and practices will need to evolve with the evidence, which will need to be nuanced regarding different types of psychosis, larger samples of ethnic groups, and comorbidities with other psychiatric and medical disorders.”

****

Bhui, K., Halvorsrud, K., Mooney, R., and Hosang, G. (2021). Is psychosis a syndemic manifestation of historical and contemporary adversity? Findings from UK biobank. British Journal of Psychiatry. (Link)

Hmm, does this article mean now anyone can say they have psychosis? This new slant seems to be being offered by those who perhaps were overly eager to dismiss the reality of those having to live with life long unendurable genuine psychosis.

Im a bit confused by this article. It seems to be one of many trying to suggest two completely different narratives…..

1. “There is NO such thing as psychosis and all a schizophrenia sufferer has is unhappiness from life’s ordeals”

2. Oh wait, everyone on the planet now has apalling psychosis, even people’s relatives and neighbours and college friends have psychosis.

Well….which is it to be?

Report comment

Daiphanous Weeping, there are many people who have experienced psychosis, but who don’t believe that they have schizophrenia. Psychosis does not have to be lifelong.

I have personally experienced a genuine psychosis (I had “voices” and delusions), but I don’t believe that I have schizophrenia. In fact, I have never had a so-called relapse despite not being on neuroleptics.

This article is not implying that psychosis is merely “unhappiness from life’s ordeals”.

Report comment

I am pleased you only had psychosis.

I have real schizophrenia.

I must say I do like your writing.

Report comment

Daiphanous Weeping, I am very happy to hear that you like my writing! As to the term “schizophrenia”, I understand why you find it useful. I think that there are no “good words” and “bad words” when people are talking about their own experiences.

Report comment

I am sorry Jenny.

You do good work.

Report comment