Those in the psychiatric profession are accustomed to talking about dose-response in terms of prescribed treatment — so many sessions per week, so many milligrams per day. Those on the receiving end are accustomed to hearing about it.

Take this at bedtime. Swallow that with breakfast. Go there for refills.

But what about non-drug prescriptions for mental health? Which regular, doable, no- or low-cost activities can alleviate stress, anxiety, and depression and contribute to a sense of well-being?

As it turns out: many.

In study after study, researchers have calculated the dose-response benefits of ordinary hobbies, habits, and lifestyle practices that are available to almost anyone, almost anywhere, without any trip to a doctor or a drugstore.

No little slips of paper covered with scrawly handwriting. No Latinate abbreviations that only a pharmacist can comprehend. No pills rattling around bottles and spilling onto the floor. Instead, the list below includes examples of daily activities that researchers have found to be good for mental health. Each links to relevant studies and, when available, an estimated allotment of time (i.e., the dose) that’s been shown to ease distress (i.e., the response).

It is not meant to be exhaustive, nor is it meant to provide formal advice. And research of this sort, typically done without much funding, is lacking in scientific rigor. But as the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed in his letter to Menoeceus:

“The search for mental health is never untimely or out of season. . . Hence we should make a practice of the things that make for happiness. For assuredly when we have this, we have everything.”

To start. . .

Physical Activity/Exercise

The benefits of exercise on physical health have long been touted in study findings and dose-response recommendations, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) pins at 150 minutes per week — or 30 minutes a day for five days.

The research and recommendations for mental health are nearly as voluminous, and nearly the same: 30 minutes a day. And that half-hour needn’t be exhausting. As one group of researchers determined in 2013, “Thirty minutes of exercise of moderate intensity, such as brisk walking for 3 days a week, is sufficient for these health benefits. Moreover, these 30 minutes need not be continuous; three 10-minute walks are believed to be as equally useful as one 30-minute walk.”

Basically, anything that gets the body moving has benefits. The same article notes an upside to all sorts of physical activity — including gardening, which boasts the added benefits of nature (see below).

And dancing, which boasts the added benefits of. . .

Music

Melody, rhythm, harmony: Research demonstrates scads of benefits for listening and participating alike.

In one randomized, controlled study from 2009-2010, older adults — sitting at their homes in Singapore — listened to their choice of music for 30 minutes per week over eight weeks total. Their depression levels reduced weekly over the longer haul, “indicating a cumulative dose effect.” The conclusion: “Listening to music can help older people to reduce their depression level.”

Another study, commissioned by the French online music service Deezer, found that, on average, people “should listen to music for 11 minutes to enjoy its therapeutic benefits.” It continued: “The only exception was happiness – participants reported feeling happier within just five minutes of listening to joyful tunes. Participants also reported feeling more satisfied with life (86%), having more energy (89%) and laughing more (65%) after listening to ‘feel-good’ songs.”

The study also advises listening to a “balanced diet” of different types of music — uplifting, calming, motivational, and so on — for a “Recommended Daily Allowance” of 78 minutes.

Actively making music has even greater benefits, as demonstrated in a 2014 exploration of its impact on pain thresholds and positive affect: “We show that singing, dancing and drumming all trigger endorphin release in contexts where merely listening to music and low energy musical activities do not.”

Research into singing specifically also suggests a dose-response relationship. Back in 2002, researchers split participants into two groups — one sang, the other listened. After just one half-hour session, “significant changes” occurred in “tension, anger, fatigue, vigor and confusion” for both groups. While the effects “were more robust” for the singing group, the authors added, “The results of this study indicate that both singing and listening to singing can alter mood immediately after participation in a short singing session.” Some of the effects were still evident after a week.

Research into dancing, such as the “5 Rhythms” approach, also suggests links with well-being; so does research into drumming, particularly drumming in groups.

Listening to music, making it, and dancing to it are all forms of. . .

Arts Engagement

Research indicates that any creative pursuit, whether active or receptive, has a positive impact on mental health. A 2021 report exploring Outcomes of Arts Engagement for both individuals and communities cited studies showing “greater happiness/life satisfaction to be associated with arts attendance at any frequency”; other research linked greater positive effects with greater frequency, starting with a once-a-week minimum.

And according to a 2011-2012 survey from Western Australia, all it takes is about two hours of arts engagement per week — or around 15 minutes a day — to nudge up the numbers on personal well-being (on the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales). Those who hit that two-hour weekly dosage “reported significantly better mental well-being than other levels of engagement,” whether that engagement is “active” (say, painting a picture) or “receptive” (say, attending a concert).

Other research has shown that going to the movies is associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety. So is knitting. So are painting and drawing. So is journaling.

So is. . .

Reading

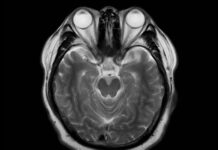

First, studies indicate it’s good for cognition — particularly print reading. Novels in particular get the brain churning, as demonstrated in one study that used magnetic resonance imaging on participants absorbed in Robert Harris’s Pompeii; results suggested reading it affected their resting brain states and increased connectivity in both the short and long term.

Second, reading for long durations isn’t required. In a 2009 study by the University of Sussex, just a six-minute dose was found to reduce stress. What’s more, reading for fun and relaxation is especially good for mental health, as demonstrated in a 2020 study of college students, which confirmed that “recreational reading was associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms over the school year.” In an earlier study examining undergraduates and stress management, researchers found that “one 30-minute session of yoga, humor, and reading had similar effects in decreasing acute stress.” (For more on the first two, see below.)

Third, some research says even owning books can improve mood. As a 2021 study of Malaysian households concluded: “Having about 11 books or more is associated with less depression, stress, less anger, and less worry.” Further, “Having books at home is positively linked to the experience of enjoyment. The positive influence was seen in those homes with more than 50 books.”

And now on to. . .

Humor and Laughter

Over the years, assorted studies have assessed the power of laughter — even short bouts of it — to de-stress college students. As one of the more recent papers on the topic demonstrated, exposure to 20 minutes of laughter therapy significantly reduced levels of anxiety and stress.

That same 20-minute dose was utilized in a 2003 study that looked at the comparative mental-health powers of exercise and humor. Both “had an equally positive effect on psychological distress and positive well-being,” the authors state. “However, humor exerted greater anxiety-lowering effect than exercise.“

Laughing with people helps. In 2011, researchers determined that social laughter can elicit an “endorphin-mediated opiate effect.” As a result, “When laughter is elicited, pain thresholds are significantly increased, whereas when subjects watched something that does not naturally elicit laughter, pain thresholds do not change (and are often lower). . . The capacity to sustain laughter for periods of several minutes at a time may exaggerate the opioid effects, thus ramping up the sense of heightened affect that humans experience in these contexts.”

And then there’s. . .

Yoga and Meditation

The ancient Hindu discipline yoking the body with meditation and breath work has piles of research highlighting its benefits for mental and physical health. One 1999 study of medical students determined that one hour of yoga twice a week for three months notably reduced their anxiety compared with a control group. A similar 2013 study, focused on middle-aged women, showed that “participation in a single 90-minute Hatha yoga class can significantly reduce perceived stress.”

Meditation alone has been shown to lower generalized anxiety and reduce stress. So has the spiritual-meditative practice known as centering prayer.

Performed at bedtime, all such mindful approaches can lead to better. . .

Sleep

The RX for Z’s depends on age.

According to a 2018 review of the dose-response research according to age, “Optimal sleep should be conceptualized as the amount of sleep needed to optimize outcomes (e.g., performance, cognitive function, mental health, physical health, quality of life, etc.).” In a table comparing various studies, it maps out the sleep recommendations by age; the National Sleep Foundation, for instance, recommends nine to 11 hours for school-age children, eight to 10 for teens, seven to nine for adults younger than 65, and seven to eight for 65 and over.

In a 2016 study of students in Japan, adolescent boys who slept for around 8.5 hours a night were at the lowest risk of depression and anxiety; in addition, a 2020 study of participants in a rural cohort in China associated lower quality of sleep with higher levels of anxiety.

The National Institutes of Health offers a guide to healthy sleep that lists all the dos and don’ts. Among other things, it cautions against alcohol before bedtime, naps after 3 p.m., and caffeine later in the day. It also suggests taking a hot bath before heading to bed.

Another factor contributing to a good night’s sleep, and mental health as a whole, is. . .

Sunshine

“Daylight is key to regulating daily sleep patterns,” urges the NIH sleep guide. “Try to get outside in natural sunlight for at least 30 minutes each day. If possible, wake up with the sun or use very bright lights in the morning. . . . If you have problems falling asleep, you should get an hour of exposure to morning sunlight and turn down the lights before bedtime.”

Even beyond its efficacy as a sleep aid, science confirms that sunshine can boost the spirits: In a 2016 Brigham Young study on sunlight and mood, seasonal increases in “sun time” were associated with decreased mental health distress. Another paper from 2019, examining the effects on 16,800 depressed and non-depressed participants aged 45 and up, found an association between “decreased exposure to sunlight and increased probability of cognitive impairment.”

Sunshine, of course, is found in. . .

Nature

Studies vary in their findings and dose recommendations, but across the board, research confirms that being in some type of green surroundings — even if it’s just a few minutes a day, whether time spent gardening or a stroll through a leafy urban neighborhood — can act as a balm.

In a multi-study meta-analysis of “green exercise” and the impact of nature on mental health, researchers found that a five-minute blast of physical activity in nearly any kind of green space yielded an immediate and marked improvement in mood and self-esteem “irrespective of duration, intensity, location, gender, age, and health status.” (Though the presence of water, for the record, “generated greater effects.”)

A 2016 study exploring specific mental and physical health benefits makes similar recommendations. “A dose-response analysis for depression and high blood pressure suggest that visits to outdoor green spaces of 30 minutes or more during the course of a week could reduce the population prevalence of these illnesses by up to 7% and 9% respectively.”

Another article, suggesting a higher dose of nature, links a minimum of 120 minutes a week with mental health. Yet another, a review of research that zeroed in on students, noted: “As little as 10 min of sitting or walking in a diverse array of natural settings significantly and positively impacted defined psychological and physiological markers of mental well-being for college-aged individuals.”

And in a 2008 Australian study examining the association between urban “greenness” and mental and physical health, people walking for recreation (rather than transport) through natural settings scored notably higher. “Those who perceived their neighbourhood as highly green had 1.37 and 1.60 times higher odds of better physical and mental health, respectively, compared with those who perceived the lowest greenness.”

In examining the mental-health impact of such leafy city walks, this same study also factors in the mental-health benefits of. . .

Social Interaction

Simply chatting with people can sharpen the mind: According to a paper from the University of Michigan, just 10 minutes per day of talking with someone helps cognition. Regarding real-world interaction specifically, a 2019 study of post-9/11 military veterans who also use Facebook demonstrated that “having in-person social contact at least a few times a week is associated with approximately 50% lower odds of screening positive for major depression and PTSD.” (In contrast, the authors said, “Increased frequency of social interaction on Facebook had no associations with mental health outcomes.”)

Beyond those dose-response takeaways, research shows that social interaction can nurture a sense of being supported and connected in the world. In a 2017 paper titled The Connection Prescription, the authors offer a long list of benefits both physical and mental:

“There is significant evidence that social support and feeling connected can help people maintain a healthy body mass index, control blood sugars, improve cancer survival, decrease cardiovascular mortality, decrease depressive symptoms, mitigate posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and improve overall mental health. The opposite of connection, social isolation, has a negative effect on health and can increase depressive symptoms as well as mortality.”

One way to connect with people? By. . .

Being a Decent and Generous Human Being

Kindness, generosity, and altruism are, researchers say, the way to go when it comes to mental health.

According a randomized 2016 study of American Presbyterians, “Helping others is associated with higher levels of mental health.” It adds: “The mental health dimension investigated in this work was composed of the anxiety and depression that plagues most people.” Other research also shows that volunteering reduces depression and increases a sense of well-being.

Acts of kindness, too, have been shown to reduce social anxiety and improve life satisfaction and well-being. Back in 2004, happiness researcher Sonja Lyubomirsky and colleagues found in a study of undergraduates that five random acts of kindness per day led to “a significant increase in well-being” over a six-week period.

A considerably smaller dose will be considered in a new study, not yet completed, that will analyze the mental-health benefits of kindness within communities in Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In recently announced protocols published by BMC Public Health, the researchers detail a randomized, controlled look at the effects of “doing at least one act of kindness per week within a four-week period.”

Finally. . .

Being Grateful

The same Lyubomirsky study exploring kindness also considered the power of gratitude over the same six-week period, concluding that students who expressed gratitude once a week “showed increases in well-being over the course of the study.”

More recently, in one randomized clinical trial, study participants who kept daily “gratitude lists” saw an increase in “positive affect, subjective happiness and life satisfaction” and reduction in “negative affect and depression symptoms.”

On this prescription, at least, scrawly handwriting might be required.

Great piece Amy, if people would take this serious it could be a life saver. Everything you mentioned here should be at the centre of the daily activity for anybody with mental health problems. And not for 30 minutes or so, but for hours per day. It should be looked at like swimming when you are in water: if you stop you drown. A combination of any activity you brought up here for a prolonged period of time will, in addition to making you feel good, heal the brain. Physically. It will make new brain cell connections, which is what a brain damaged by pharmaceuticals, needs. The only thing I missed here was sexual activity. https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-sex-health-benefits

It will have much of the same effects as the other activities you listed.

Report comment

Thanks! And yes, certainly there are lots of activities and elements of living that benefit well-being but I didn’t include. The list goes on. That’s one reason I included that little “not meant to be exhaustive” disclaimer. I realized, in the thick of working on this, that if I didn’t limit the scope of it, the story would go on more or less forever.

Report comment

You are right of course.

What I find very disheartening is that no one seems to pick up on this. Treatment and health is on their finger tips and it is so hard to convince people to go for it. Apart from me, not one reaction, I just don’t get it….

Report comment

In all my years of being in “psych world”, I had only one psychiatrist or therapist who suggested that I walk every day, if possible. I did have one therapist who suggested that I take free courses with the local university. And I was involved with a ceramics group in day program. However, they basically either sold or stole my work and the others who were involved, too. The did, however, take us for a shopping trip at the mall and a lunch at a local cafeteria. But, if you consider that the psych drugs basically put you into “zombie land” you are lucky that you can be awake enough to engage in any of the activities mentioned in this article. Oh yes, in another day program there was a poetry group and there was a small group making mosaics. Art, music, writing and being in nature are definately preferable to any drugs or therapies. But not everyone has talent in art, music, writing, etc. So, I think above all else and this would prevent destoying peoples’ lives via psychiatry, etc. is to help people find out what they are naturally talented doing and what they enjoy doing. But, neither a drug nor psychotherapy as it usually practiced presently can do that! Oh well! Thank you.

Report comment

Dear Rebel, you don’t need talent to get involved in any of this. The mere fact of engaging in these activities is beneficial and therapeutic. You don’t even have to enjoy it, just go for it. Like running/jogging/fast walking/crawling, what ever, leads to new connections in the brain. Psychoactive medication destroys brain cells, exercise create new brain cell, what is there not to like? Nike is right with their slogan (Just do it!)

Report comment

Whether one needs talent or not to engage in something is entirely up to that person. Yes, what you call “psychoactive” or rather “psychiatric” or “psychadelic” does destroy brain cells to the point it can alter the brain towards brain damage. And, yes, doing all kinds of things do lead to new connections in the brain and that can be helpful. However, I disagree in that I can see absolutely no reason to do something (unless you have to; like clean the bathroom or pay this month’s bills) that you do not enjoy. It is imperative that what we do choose to do in almost all instances and it is even more necessary if you are in recovery from psych drugs that is enjoyable to us. If it is not, we just progress bacwards until we are back at that most most vulnerable and gullible place where we fall in the tyranny of psychiatrists, etc. As for the talent thing, I would say it is our choice as to whether what we do involves using any of our talents. However, if you lack the talent for something, it is usually not quite that enjoyable and so usually no more clear benefit. The great basketball coach, John Wooden, always advised, “Do not permit what you cannot do with to interfere with what you can do.” This sounds like good advice, whether or not you have had the horrific misfortune of having your brain damaged by psych drugs or not. So, the old Nike slogan of “Just do It” might be modified to “if you enjoy it then do it!.” Thank you.

Report comment

Oh yes!! We just need to get back to “being human” again–and encouraging each other in these ways! Eliminate the toxic drugs and encounter the beauties of the world. I use art and Bach–every day! Thank you!

Report comment

Amy, this is excellent advice throughout your piece. To revert to living in the body, in civilised communities, and helping maintain, improve or create them where possible, helping others in need, taking care, participating in the arts (dance, drawing, painting, music, literature) as the late Sir Ken Robinson advocated in schools – he considered creativity to be the essential act of living and finding a way through a changing and unpredictable world. In line with what you have written.

Like you, we could all take up, or continue, the activities you mention and encourage doctors and therapists to do the same and to recommend it to those who are suffering with emotional, psychological and mental difficulties. Because it works!

See TED talk ‘Do schools kill creativity’ with Ken Robinson: https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity

Report comment

While psychiatrists are accustomed to speaking about dose-response in terms of prescribed treatments, those experiencing mental health issues are familiar with receiving such advice as well. Things become much more intricate when considering non-drug prescriptions for mental health such as a daily routine activities that are readily available and cost-effective. Research has consistently demonstrated the beneficial ( https://www.cambiati.com/product/primal-multi-new/ ) effects of physical activity on both physical and mental health. According to the Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention (CDC), the recommended dose of exercise is 150 minutes per week or 30 minutes per day for five out of seven days.

Report comment