Brazil’s mental health community has long taken pride in its 1980s psychiatric reform. The shutting of hospitals was accompanied by the passage of progressive legislation for creating community-centered care and protecting the human rights of patients. Mad in Brasil’s goal today is to move on from that earlier reform and foment a second wave of profound change.

As is true of all Mad in America affiliates, Mad in Brasil want to see a transformation of the current drug-based paradigm of care.

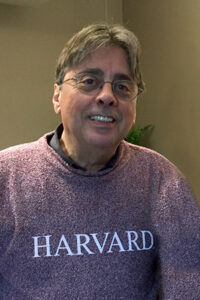

“[We want] to promote, to create, a radical rupture—a break—a radical rupture in our relation to the psychiatric model,” said Fernando de Freitas, psychologist and co-creator of the site.

That means going beyond Brazil’s history of dehospitalization into a new model that challenges and redefines the very nature of psychiatric care. Even in a community-centered approach, the same prevailing medicalized elements need to be reconsidered: The reliance on diagnoses. The emphasis on drugs. The overarching impact of the paradigm itself.

“Questioning its concepts and practices”—that, Freitas said, is everything. “To reflect, to re-think, to question. We want to change the conversation.”

For the last five years, that quest has fueled the work at Mad in Brasil. Founded by Freitas and preeminent Brazilian psychiatrist Paulo Amarante—the driving force behind the country’s groundbreaking 1980s psychiatric-reform—the MIA affiliate is based at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, the globally influential public-health research center based in Rio de Janeiro and known widely as Fiocruz.

The past provides reason for Mad in Brasil’s leaders to believe that a paradigm shift is possible. In the early 1980s, Freitas explained, “We initiated a psychiatric reform process in Brazil inspired by the Italian psychiatric reform” movement of the 1970s. That campaign, led by psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, culminated in the Italian Mental Health Act of 1978—known as the “Basaglia Law”—and shuttered psychiatric hospitals in favor of community-based mental healthcare.

The subsequent Brazilian reform used a similar approach, pairing deinstitutionalization with the establishment of Psychosocial Care Centers, also known as CAPS. Some 40 years later, the country has 2,661. “The goal was to replace the hospitalization model [with] a community model of care,” Freitas said. Beyond that, in 2001 a federal law was created “providing for the protection and the rights of people with mental disorders.”

But the paradigm needs to be challenged further, he said. Several years ago, after reading Anatomy of an Epidemic and other work by Mad in America’s Robert Whitaker, Freitas and Amarante reached out and invited him to an international seminar at Fiocruz. Sometime later, Whitaker suggested Freitas and Amarante create an affiliate of MIA. Mad in Brasil was born.

That was summer of 2016. The natural base of Mad in Brasil’s operations was Fiocruz, where Amarante, now retired, had created the Laboratory of Studies and Research in Mental Health (LAPS), where both he and Freitas worked as professors and researchers.

Perhaps someday, Freitas said, Mad in Brasil might break away from Fiocruz into a separate organization with separate funding. But at the moment, it has no other source—aside from his own small contributions boosting Mad in Brasil’s Facebook posts. (There’s also a Mad in Brasil Instagram page.)

Most of the Mad in Brasil’s written content consists of work from other Mad in the World outlets. Freitas spends hours translating articles posted on Mad in America, Mad in the UK, and sometimes Mad in Italy. Traditionally, he noted, Brazil does not produce much original research. Also traditionally, Brazilians are reluctant to write up their own stories of lived experience. A student, Camila Mota, also posts weekly reviews of publications from Brazilian research journals.

Further complicating matters is the pandemic, which moved MIB operations from Fiocruz—and its research-publication portal—to Freitas’ home. Once COVID allows a return to the center, he hopes to resume video segments for TV Mad in Brasil, including interviews and weekly 20-minute roundups. All of that will be easier with the higher-quality sound and lighting available at Fiocruz.

In the future, he also hopes to coordinate and collaborate more with Mad in Italy, including plans for a joint international seminar on the legacy of Basaglia. That, he added, is an example of the “collective” work that Mad in Brasil envisions with the Mad in the World network.

Beyond all such goals for Mad in Brasil—underscoring everything that Freitas hopes to accomplish—is the need to keep altering the conversation around mental health, to keep challenging the paradigm. Although Brazil remains among the most progressive countries in that regard, much, he said, still needs to be done. The drug model still prevails; the DSM still reigns; even within the community-based CAPS centers, people still need a diagnosis to receive any funding or care. And many still believe such diagnoses are lifelong, chronic conditions.

The system needs to shift away from such “psychiatrization” of mental health care, he said. “People receive a lot, a lot, of psychiatric drugs. . . . It’s very common, and people are dependent on these treatments,” said Freitas, co-author of Medication in Psychiatry. “And people are dependent on these treatments, these psychopharmacological treatments.” This despite the effectiveness and availability of psychotherapy and community-based psychosocial approaches that include, for instance, soccer teams that integrate service users with people from the wider community.

In Freitas’ view, many Brazilians simply need to be informed of an alternate, drug-free path—because they’ve never been told there’s another way. This is what he hopes to accomplish through Mad in Brasil and the work of the wider Mad in the World affiliates. This is its impact so far and its mission moving forward: gradually bringing new concepts, new ways of thinking, to new readers.

Although he understands many are resistant to change, Freitas believes that there are also many in the field who, exposed to new information and new ways of thinking, are open to change: “Students of psychology, students of medicine, social work students, and users,” he said.

“Above all,” he said, those are exactly the types of readers Mad in Brasil wants to reach: those caught in the current, DSM-centric, heavily medicalized model. Right now, “They don’t have access to this information. They don’t have access. So it is very important—very important” what Mad in Brasil and other MIA affiliates are working to achieve.

All of his efforts, all of his strategies, have one clear goal: “To reach more people,” he said. “That’s exactly it.”

*****

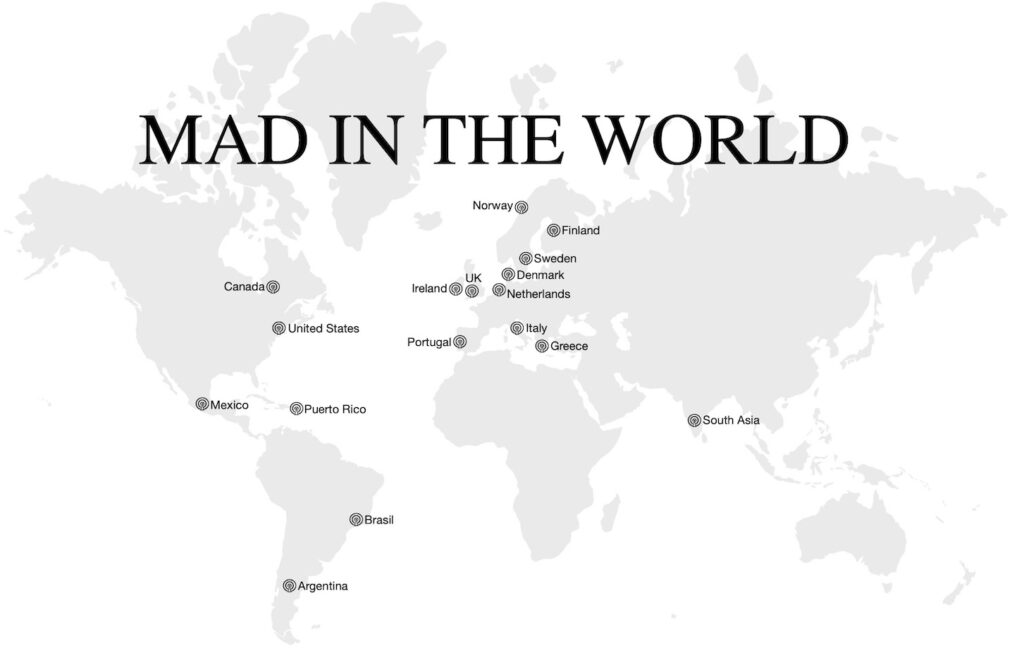

MIA Editors: Over the next 10 weeks, we will be publishing a profile of each of the Mad in America affiliates. They have banded together as a “Mad in the World” network.

Good one

Report comment

The only way psychiatry can ever “change” is, IF they smell it coming. That is the only reason some shrinks seem “open to change”. They talk, but no, they are not open. If they were, they would lose their jobs.

They hold those steadfast convictions, which ironically, they try to get “those other people”, to change.

Best thing to do, is try to catch people before they ever seek help from any medical based community, AND shrinks.

Report comment