In recounting the history of mental health treatment and psychosis, the dominant voices often belong to academics and “professional experts,” marginalizing the perspectives of service users with lived experience of psychosis and mental health services. This omission obscures the long and rich history of service user-led social movements which have bravely challenged psychiatric authority for decades.

In a new article, Berta Britz and Nev Jones, themselves service users, argue that if we do not recenter and uplift the voices of those with lived experience, we will never see transformative change in mental health treatment and policy.

“When those who have been most silenced meet in common thresholds, truly transformative change will happen,” Britz and Jones write. “The systems and people closest to the top and next layers down won’t conceive of new possibilities until their eyes, hearts, and minds open to the co-creations of those of us with ‘lived experience,’ we who have been classified, objectified, and harmed.”

For decades, psychiatry has wielded the power to diagnose, institutionalize, and subject service users to treatments, including medication and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), frequently against their will. Even when this critical side of history is told, it is still written by “professionals” and not from the first-person perspective of current and former service users.

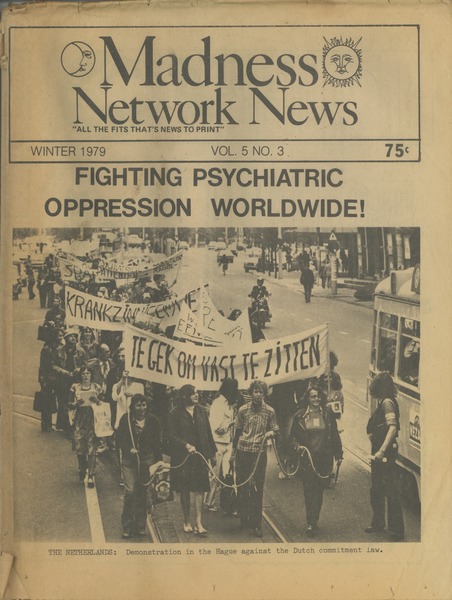

Historically service users were silenced to the point that they resorted to communicating through hidden channels – such as the Madness Network News (MNN) — a widely circulated journal founded by two inpatients in a California State Mental Hospital. This communication platform was used to discuss unjust treatment experiences, organize social movements, and collectively resist psychiatric authority. (MNN maintains an active archive and blog at www.madnessnetworknews.com.)

In this new article, authors Berta Britz, a certified peer specialist, and Nev Jones, a University of Pittsburgh assistant professor, fuse their personal experiences with psychosis and archival resources from ‘underground newspapers’ like MNN to engage with this largely untold counter-history.

From the genesis of the Ex-Patients Movement in the 1960s-70s to modern activism addressing experiences traditionally labeled as psychosis, they recast the history of psychosis and mental health treatment through the lens of service users.

They contend that to root social justice in “policy, scholarship, and practice,” we must honor the “stories user/survivors tell—stories of trauma and voices…stories of abuse in psychiatric settings, or isolation and misrecognition,” asserting that these narratives “must be believed, engaged with, and acted on.”

The narratives of service users and psychiatric survivors that have emerged create a compelling counter-history:

Ex-Patient Movement (1960s -1970s)

Seen as a crucial shift toward more compassionate support for those with mental illness diagnoses, the Ex-Patient Movement was propelled by the signing of the Community Mental Health Act in 1963, which moved people from large psychiatric institutions to community-based mental healthcare.

The narrative often overlooks the proactive role service users played in instigating this change, as they sought to “change the archaic and repressive aspects of the psychiatric treatment centers” through initiatives like workshops where therapists could learn about the other side of madness from those who have experienced it.

In Madness Network News, service users discussed “trying to change the archaic and repressive aspects of the psychiatric treatment centers” through interventions such as service users holding “workshops for therapists and others to learn about the other side of madness from those who have been there.”

Contesting “Forced Chemotherapy (1970s – 1980s)

After the Community Mental Health Act (1963) ended long-term institutionalization, many ex-patients suffered the harmful side effects of prolonged use of psychiatric drugs and ECT.

A 1983 article by ex-patient activist Linda Ladew observed that “[phenothiazines] seriously diminish one’s intellectual effectiveness and severely compromise one’s emotional integrity. [Nevertheless] psychiatrists [argue that] deterioration is [simply] part of the natural history of schizophrenia.”

Similar conversations about the unwanted side effects of medications, along with comedy sketches and other ways to raise awareness, prompted many “ex-patients” to fight against the use of forced medication. This ultimately led to a major victory where forcible injections were outlawed – Judge Joseph Touro explained that:

“…subjecting a patient to the humiliation of being disrobed and then injected with drugs powerful enough to immobilize both body and mind is totally unreasonable by any standard.”

For years to come, this legal case served as the basis to fight other forms of forced treatment.

Deinstitutionalization and Reinstitutionalization (1980s-1990s)

During this period, ex-patient activist Howard Geld highlighted the significant leadership role of “educated” and middle-class individuals in ex-patient social movements. Unfortunately, this narrative underplays the detrimental impact of flawed government policies and discriminatory beliefs about ex-patients, many of whom became homeless and jobless.

Adding insights from her own experiences, Nev Jones writes that “the temptation is so often to look back at history and say, “wow, providers back then were so naïve, so racist, so ableist; we’re not that way anymore…But even in 2009, I was terminated from my graduate program under the premise that “someone like me” would never work, could never “repay student loans,” and that, therefore, program termination was “in my best interest.”

Race, Structural Racism, and Erasure (1970s – 1990s)

The use of psychiatry to enforce racism and oppress racial minority communities, particularly during the Civil Rights Movement, is another overlooked aspect of history. Psychiatrists diagnosed “protest psychosis” to institutionalize Black men and label them schizophrenic at the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane for protesting for freedom and human rights.

Berta Britz describes how she was also hospitalized for psychosis at a nearby location. However, she reflects that “Iona was used for social control. I – a white woman – was considered a less dangerous “schizophrenic” and was taken to a “therapeutic community” instead.

Despite this, Black and Brown ex-patients continued to engage in anti-racist organizing to call attention to psychiatry’s use of racist belief systems to control racial minorities. Luisah Teish, a Black feminist survivor activist, wrote in the Madness Network News:

“We know that if sanity is defined by white upper-middle-class standards, then we are in grave danger” and then emphasized that Blacks were at risk of being “lock[ed]…up.”

Power, cooptation, and user-led alternatives: Late 1970s – 2010s

In 1978, activist Judi Chamberlin championed mental healthcare led by peers—services provided by those with lived experiences of mental illness or psychosis.

Although peer-led services are often framed as progressive, service users argue that this is “superficial inclusion” because peers are forced to follow psychiatry’s beliefs about effective treatment rather than having their own input. In Berta’s reflection on her experience, she argues that peer specialists have little say in the design and implementation of services because those “in control of official resources” have the most power.

Contemporary Activism Focused on Experiences Traditionally Labelled as Psychosis

Contemporary activism reveals that the service user movement has not gone silent. One current effort includes the Hearing Voices Movement – which promotes alternative ways of understanding the experiences of those who hear voices. Other efforts center on the safe withdrawal and tapering of psychiatric drugs. Along with Mad In America, other forums – such as Madness Radio and Unapologetically Black Unicorns – work to rethink psychiatric care.

The academic writing on the history of mental health treatment and psychosis has erased the voices of service users and activists. Such silencing marginalizes or dismisses the experiences and work of activists and service users.

Furthermore, research on how to improve the use of service users in peer-led services and academic research continues to be important in contemporary activism. Uplifting service-user voices is vital because this history will shape how we understand the past and how we will proceed to the future. Articles such as this not only unmask the truth but also honor experiences from the past and empower current service users.

**

To support this cause, if you are someone with “lived experience,” Mad In America invites you to submit a personal story. You can also uplift those who have bravely done so already.

****

Britz, B., & Jones, N. (2023). Experiencing and treating ‘madness’ in the United States circa 1967–2022: Critical counter-histories. SSM – Mental Health, 100228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100228 (Link)

Hello Tiffani, Not all survivors of psychiatric atrocities care to support your academic career or this blog site with their free labor. MIA could help by elevating the stories of those who choose to participate to a level equal to the clinical people (like you) who write her to promote their paid activities instead of putting them in their own little “personal stories” section.

Report comment

Maybe MIA could put together an anthology of personal stories and give the proceeds to the authors.

Report comment

I agree with the previous two commenters. It’s about time academics and “clinicians” stopped looking to feed off the misery of others in order to advance their careers. And it’s about time MIA stopped acting as their accomplice.

Report comment

Good to see you still attempting to navigate the academic/clinical swamp that MIA has become.

The reason they tolerate you is that you can be used to demonstrate that MIA listens to “all sides.”

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I have to admit to wondering about that…

Report comment

“academic/clinical swamp”. LOVE THOSE WORDS.

Report comment

Tolerance hides arrogance.

Report comment

And guess what? I DON’T GIVE A SHIT.

Report comment

The root of the problem lies in believing that people’s life experience doesn’t matter until the culture vultures deign to “study” it.

Report comment

Can you document that? 🙂

Report comment

That’s easy. Just scroll the “Research News” section in MIA. 🙂

Report comment

It is very strange that on the topic of psychiatry and it’s harms, the voices people who have first hand experience don’t count as much (and not just on MIA) as people who have studied the subject.

Like, if I want to learn about the Brazilian rainforest, should I learn from people who’ve never been there but have read all of the major books and articles about the rainforest, or should I learn from someone who’s spent most of their life in the rainforest (and who wrote a book about the experience but couldn’t get it published)?

At the very least, those two sources of knowledge (book knowledge vs first hand experience) should be given equal weight.

Report comment

First-hand experience outweighs the DSM, hands down.

Report comment

God does it piss me off to see publications such as Madness Network News — which always presented itself as an ANTI-PSYCHIATRY publication produced by ex-PSYCHIATRIC INMATES (not “mental patients”) — used to claim that the movement circa 1970-80 had something to do with improving psychiatry rather than abolishing it. BTW the clique that has attempted to steal the legacy of MNN has nothing to do with the original movement other than to borrow the names of a few Madness collective members who are no longer actively fighting psychiatry.

Report comment

It’s just a sophisticated form of virtue signaling. Or carpetbagging.

Report comment

Yeah, how nice would it be if academics and clinicians actually respected those activists enough to pay them like the experts they are when they write their little articles instead of co-opting graphics of things like “Madness Network News” and then demanding that they, with their whopping 5 or so years of experience, be treated like the experts on these topics. I daresay that is a huge part of the reason some of the best activists we ever had are no longer actively fighting psychiatry (as you say here). What a sad state of affairs. And, I guess that about wraps up this discussion, LOL.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I would actually encourage everyone to check out the old copies of Madness Network News that have been put online.

I would however strongly caution that the people who have published these documents DO NOT represent the anti-psychiatry movement or the MNN collective and their agenda is their own.

But if you stick with the original MNN you can’t go wrong.

Report comment

As one of the main editors of Madness Network News (1974-1986ish), I object to the co-option of our name and graphics to support the concept of paying attention to the voices of “users” of psychiatry. It’s true that in the very early days of MNN (before i got involved) there may have been more of a focus of getting mental health professionals to pay attention to what “users” had to say, but for most of its 14 years of existence, when it was completely created by survivors of psychiatry (with the exception of the husband of one psychiatric survivor), the focus of the paper was entirely on abolishing forced psychiatric treatment and validating “mad” states of mind.

The editors and contributors of Madness Network News did not consider themselves to be users of psychiatry because it was never their choice to be recipients of mental health services to begin with. Thank you, yinyang for encouraging everyone to check out the original copies of MNN that have now been put online at madnessnetworknews.com. (Also all the old copies of our sister Canadian journal, Phoenix Rising). We, the former MNN editors, gave our blessing to this new site and are immensely appreciative of them making all the back issues available. We have not attempted to monitor the content of the new MNN site, feeling that the back issues speak for themselves and most of the original editors are now dead or well past retirement age.

It’s not true that none of us are any longer engaged in fighting psychiatry, however. I wrote a long history of the early anti psychiatry/ psychiatric survivor movement, and the history of Madness Networks News, which can be found here at MIA. I’ve been making this available to people in various online groups who want to learn more about the early (i.e. authentic) anti psychiatry movement. Currently i am engaged in a lost campaign to convince the National Association of Rights Protection and Advocacy to end their disgusting and pro-forced-treatment policy or requiring attendees at their national conferences to show proof of covid vaccination and wear masks. https://www.opednews.com/articles/Why-is-a-Rights-Protectio-Cdc-Changed-Guidance-On-Covid_Experimental-Covid-Vaccines_Higher-Death-Rate-In-Those-Who-Received-Covid-Vacc_Informed-Consent-Or-Refusal-To-Treatment-230527-875.html

Report comment