Many people who know almost nothing else about the mental health system can nevertheless recount the story of the “failure” of “deinstitutionalization” in America. The story is repeated so often that it’s widely accepted as if it were a famously indisputable math formula:

Large state hospital asylums started closing decades ago, but promised community beds and services never came. As a result, today, there’s a disastrous bed shortage and huge populations of untreated, severely mentally ill people are homeless or in prisons.

Any numbers provided are close to these:

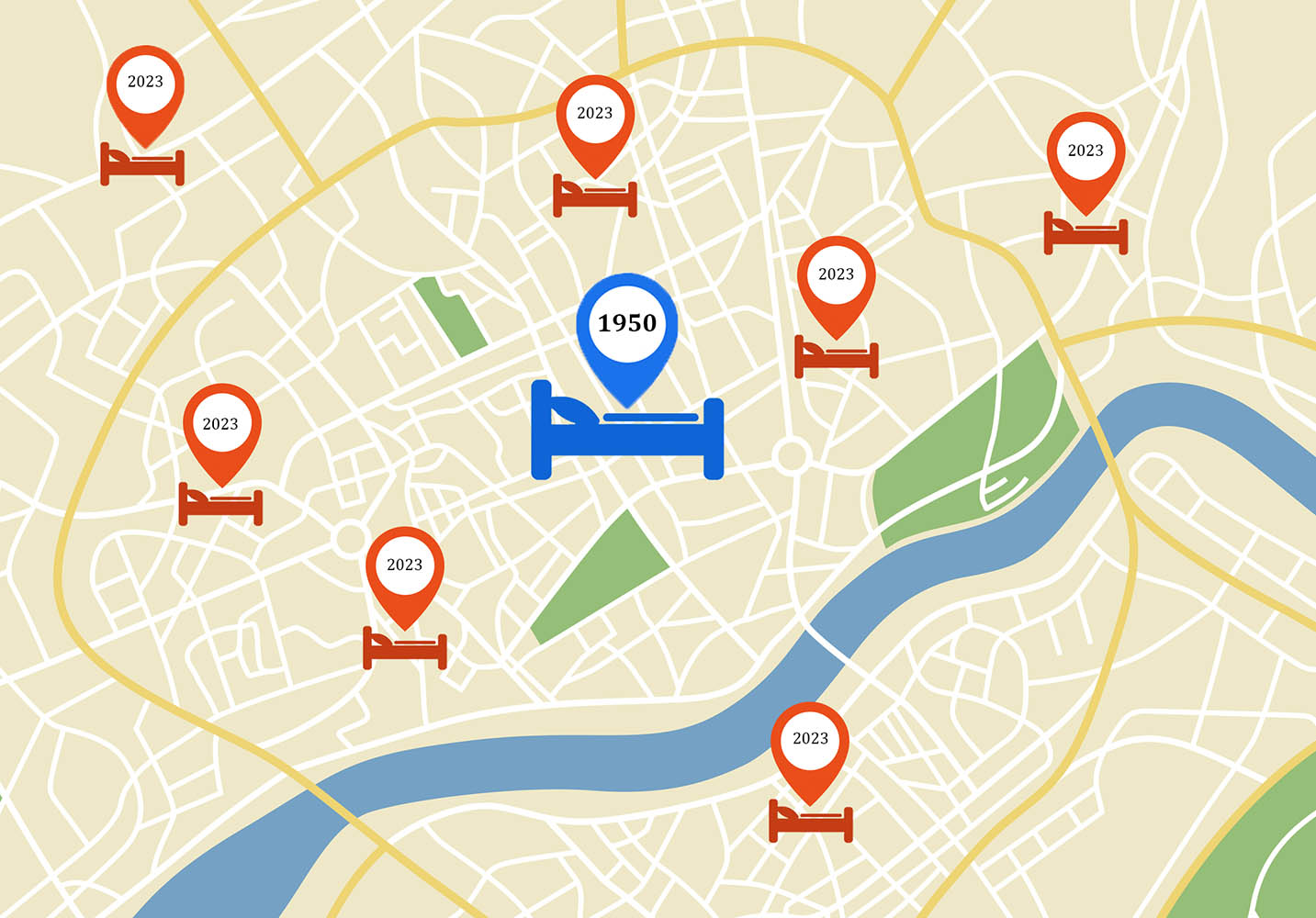

In the 1950s, there were about 550,000 state hospital psychiatric beds, or 330 beds per 100,000 people. Today, there are only 37,000 state hospital psychiatric beds, or about 11 beds per 100,000 people.

For the past two decades, this story has been regularly re-told everywhere from popular right-wing periodicals like The Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Breitbart, through mainstream and left-liberal sources like The New York Times, NPR, PBS, The Daily Beast and The New Yorker, to investigative news outlets like Mother Jones and Kaiser Health News. The story also plays a central role in political lobbying by mental health organizations and providers, in Democrat and Republican platforms, and in public education by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Essentially, this deinstitutionalization disaster story has become a culture-wide dominant narrative. It has fueled beliefs that compassionate improvement of the mental health system—and help for the unhoused and imprisoned—requires bringing back more psychiatric beds and coercively treating more people. Even those who critique pro-force sentiments in outlets like The Nation nevertheless frequently echo the dominant narrative’s basic elements.

However, in 2017, the U.S. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD)—the people who actually oversee America’s mental health systems—quietly fact-checked this dominant narrative. Their resulting report showed that these oft-repeated bed numbers are not only inaccurate but wildly misleading.

And from the real numbers, there emerges a fundamentally different portrait of America’s mental health system, its impacts on society, and what’s gone wrong. It’s a picture of an America where there’s never in history been more psychiatric beds per capita, or more widespread psychiatric monitoring and coercion.

Where and why did the viral disinformation start?

If you’ve ever been a psychiatric patient or worked in community mental health in America or, like me, regularly talked with people from both these groups, something quickly becomes obvious: State hospitals rarely get mentioned. Much more commonly, people mention general hospital psychiatric wards, private psychiatric hospitals, group homes, assisted living facilities, nursing homes, and other institutions and services. And in fact, only 1.6 percent of people getting public mental health care in 2020 got it in state hospitals.

So, why has so much public attention focused on state hospital bed numbers?

Reading the above-cited news stories, the answer becomes obvious: Every one cited, quoted, was co-written, or otherwise involved the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC), its oft-quoted report about declining state hospital bed numbers “Going, Going, Gone,” and/or TAC’s founder, psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey. And not coincidentally, rivaled perhaps only by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, TAC and Torrey have long been this country’s most well-funded and influential lobbyists for expanding forced psychiatric treatment. Indeed, when New York Mayor Eric Adams recently called for more aggressive uses of psychiatric detention powers, The New York Times dubbed it a “coronation” for TAC and Torrey.

TAC and Torrey have focused attention on eye-catching state hospital bed-number declines to help push their campaigns for expanding coercive treatment, and they’ve been extremely successful. In my book Your Consent Is Not Required: The Rise in Psychiatric Detentions, Forced Treatment, and Abusive Guardianships, I show the consequences: Rates of coercive psychiatric interventions have been rising dramatically for several decades as broadening mental health laws get used against ever-wider ranges of people and in many institutions from schools, government housing, and workplaces to mental health hotlines and nursing homes.

So, how can coercive psychiatric interventions be rising amid a purported catastrophic shortage of beds? The answer is that “bed capacity” in the United States has steadily expanded in step with that rise.

Resurgent interest in the facts

TAC and Torrey’s story has rallied support for increased mental health funding and more aggressive forced drugging laws, but it’s always been too far divorced from reality to guide on-the-ground, day-to-day decision-making. Knowledgeable mental health system leaders know that most beds and services today are outside state hospitals, and that expanding hospital psychiatric care is, by far, the most expensive of all possible options. And even the American Psychiatric Association (APA) quietly recognizes that scientific evidence of the helpfulness of psychiatric hospitalization is “absent.”

So, no new large asylums have been built. Instead, under mounting public pressure to solve the nation’s seeming “mental health crisis,” mainstream mental health system leaders are showing a resurgent interest in understanding how many psychiatric beds of which types actually do exist in America, and may optimally be needed.

One question that needs answering first is, “A half-century after most asylums closed, what is a psychiatric bed today?”

A team of researchers from the RAND Corporation recently published a viewpoint in JAMA Psychiatry, “Estimating Psychiatric Bed Shortages in the US.” The authors described it as “worrisome” that “there are no standardized approaches or best practices” for determining what a “psychiatric bed” is—let alone how many are needed or what causes an apparent “shortage.”

Broadly, publicly funded psychiatric beds can be divided into two main categories:

Category 1: Inpatient beds in hospitals or hospital-like settings that are able to provide 24/7 intensive psychiatric care.

Category 2: Residential beds in the community where people labeled with mental illnesses live in home-like settings and receive any of varying amounts of publicly funded voluntary or involuntary mental health treatments and practical supports.

In the 1950s, asylums were the predominant location for both of these categories of beds. Today, there are many variants of both, and the divisions are not always clear cut—for example, residential treatment centers are inpatient institutions that also have residential beds.

There also aren’t standardized, completely reliable ways to find and count psychiatric beds, the RAND authors explained.

Generally, a facility’s bed numbers are included in licensing information—however, at any time that number may not correspond to staffed beds, different types of facilities may be overseen by different government departments, and some common bed types, such as supportive housing for people labeled with mental illnesses, may not require licensing at all. One can also count psychiatric “patients in beds” on one selected day—but any day may not accurately reflect other days or full capacity. Another method is to count an institution’s “discharges” linked to treatment for mental disorders.

Then, to understand shortages, one has to track how different types of beds and services interact. For example, there may appear to be a shortage of hospital psychiatric beds when there’s actually a shortage of supportive housing to move people into when they’re ready for discharge from hospitals. Or, when patient case managers don’t have access to frequently updated directories of all available beds in their area, then shortages can seem common even when they’re not.

Consequently, counting psychiatric beds and illustrating trends across time and population changes involves “cobbling together” data from different sources, drawing estimates from studies and surveys that may have been done in different years in different ways, and “roughing in” calculations. Yet, the very complexity highlights the operational importance of gaining better understanding.

So, the NASMHPD decided to take on the task of counting psychiatric beds in America. And their data and analyses make it clear that the dominant narrative about deinstitutionalization is completely off-base.

The reports that are shifting the dominant narrative

As of 2023, there are four related reports that, together, have started to shift the dominant narrative.

Most importantly, published in 2017 by NRI, the research institute of the NASMHPD, the report “Trends in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014” provided a comprehensive, nation-wide count of beds in category 1—inpatient psychiatric beds in hospitals or hospital-like settings.

In 2019, SAMHSA issued “Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum.” This report drew on the NASMHPD report’s data and examined how psychiatric bed numbers and types have changed historically alongside changing standards of coercive care.

In 2022, the APA released “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the U.S.: Understanding the Problem and Moving Toward Solutions.” The APA also drew on the NASMHPD report’s data and began to do modeling of how many beds of which types might be required to provide an optimal continuum of care in a typical community.

Later in 2022, the NASMHPD published an update to its own report, showing bed-number trends to 2018.

In this review and analysis, I’ll refer to these reports as the NASMHPD, SAMHSA, and APA reports. I also interviewed Ted Lutterman, lead researcher for the NASMHPD reports, in 2021 for my book, and again in 2023 for this article.

In conversation, Lutterman has repeatedly made the gist of his findings clear: “E. Fuller Torrey or others are always talking about how there used to be half a million people in state hospitals, and if we had that number of beds today, at equivalent rates, we’d need so many beds.” However, Lutterman said, the widely cited numbers promoted by Torrey, TAC, and many politicians and media outlets “just don’t add up.”

Both the APA and SAMHSA reports also challenged TAC and Torrey’s main claims. The SAMHSA contracted-researchers accused “E. Fuller Torrey and colleagues from the Treatment Advocacy Center” of promoting bed numbers and comparisons that were neither “apt” nor truly “meaningful.” Irked by inflammatory claims that prisons are “the new asylums,” the researchers countered that “nearly 20 times more people with a serious mental illness today receive care in the nation’s public mental health systems than are housed in its jails and prisons.” In a similar vein, the APA report noted that every study that has actually tracked discharged asylum patients found that only miniscule percentages ever became homeless or imprisoned.

So, what do the real numbers show?

First, there were nowhere near as many psychiatric beds in the 1950s as Torrey and TAC have continually claimed.

How many inpatient beds existed in the era of large asylums

In the 1950s, nearly all psychiatric beds in America were in state/county hospitals. The NASMHPD reports pointed out, however, that state hospitals in that era held many non-psychiatric patients as well. The SAMHSA report similarly acknowledged (as did the APA report) that “large swaths” of state hospital patients used to include people with tuberculosis, epilepsy, syphilis, elderly dementia, alcohol problems, and intellectual or developmental disabilities. These are people who today receive services in other types of facilities that have themselves increased immensely in number over the decades, such as ordinary medical hospitals, nursing homes, “sober homes,” and institutional homes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Focusing on psychiatric beds only, Lutterman found reliable data showing that, even as late as 1969, only 58 percent of state hospital patients were psychiatric patients. So, the actual number of state hospital psychiatric beds in 1969 was 42 percent lower than the number commonly cited in the dominant narrative.

Although the percentages from the 1950s appear to roughly parallel the 1969 numbers, Lutterman told me that he was reluctant to use that data due to the murkiness of both psychiatric diagnoses and state hospital admission criteria in that era. I asked him if he generally believed the true percentage of non-psychiatric beds in state hospitals would have been smaller or larger in the 1950s. “It’s unclear, but it sounds like it would be even larger,” Lutterman answered. “[State hospitals] were sort of a catch-all place [for people] that society didn’t know what else to do with.”

So, there were not 550,000 state hospital psychiatric beds in the 1950s, but more likely, at most, 58 percent of that number—about 319,000 state hospital psychiatric beds. Roughly accounting for national population changes during that decade, this was about 190 state hospital psychiatric beds per 100,000 people in the 1950s.

And by comparison, how many inpatient psychiatric beds exist in America today?

Counting category 1: The number of inpatient psychiatric beds that exist today

As the so-called “deinstitutionalization” movement gained traction from the 1960s to ‘80s, large state and county hospitals were closing. However, contrary to the dominant narrative, smaller psychiatric hospitals, institutions, and community-based beds, facilities, and services began multiplying and receiving enormous increases in funding.

In reviewing this history in the NASMHPD reports, Lutterman focused on counting “inpatient” beds—hospitals or hospital-like residential facilities. Aside from state/county hospitals, these include:

- Private psychiatric hospitals

- General hospitals with psychiatric wards

- Veterans Administration (VA) medical centers

- Community mental health centers

- Residential treatment centers

- Other crisis care facilities

VA and state hospital bed numbers have indeed declined a lot, but Lutterman found that bed numbers (or the total number of patients on a selected day) in many other facilities increased considerably from 1970 to 2018. Beds in private psychiatric hospitals increased nearly five-fold to 54,396. Residential treatment center beds nearly tripled to 36,845 beds. Beds in general hospitals more than doubled to 40,530.

Among these, Lutterman found 187,877 inpatient psychiatric beds in America in 2018. That’s about 57 beds per 100,000 people—five times as many inpatient psychiatric beds as the “11 beds per 100,000” number that is commonly publicly cited in deinstitutionalization disaster stories.

And Lutterman found still more.

Nursing homes exploded in number in the late 1950s and ‘60s, supported by enabling legislation and the launch of Medicare and Medicaid. Although mainly for frail seniors, the reports from NASMHPD, SAMHSA, and the APA all acknowledged that nursing homes have become a common inpatient setting where psychiatric patients also get placed. These include large numbers of adults who are not elderly and/or do not have dementia or disabling physical conditions. No one is formally tracking how many ordinary psychiatric patients stay in nursing homes, but in some states thousands have been identified in Department of Justice lawsuits targeting them as unnecessarily restrictive, coercive settings for most psychiatric patients.

Since these are usually people diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, Lutterman used data quantifying the number of nursing home residents diagnosed with what are typically regarded as serious mental illnesses: bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. These comprised 13 percent of nursing home residents. Lutterman advised “caution” about the precision of the number, but this calculation added 223,917 patients—another 67 beds per 100,000 people.

The table below shows the main types of inpatient psychiatric beds in America that Lutterman could reliably quantify—with corresponding calculations of beds per 100,000 people to facilitate comparisons over time relative to population growth.

| Number and Rate per 100,000 population of psychiatric inpatients and other 24-hour residential treatment patients at end of year 2018. (Excerpted with decimal-rounding adjusted from Table 1 and Table 5, “Trends in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity: United States and Each State, 1970 to 2018.”) | ||

| Type of Organization | Patients in Inpatient and Other 24-Hour Residential Treatment Beds at End of Year | |

| Residents/Beds | Rate Per 100,000 Population | |

| State & County Psychiatric Hospitals | 35,725 | 10.9 |

| Private Psychiatric Hospitals | 54,396 | 16.6 |

| General Hospital with Separate Psychiatric Units | 40,530 | 12.4 |

| Veterans Administration Medical Centers | 6,992 | 2.1 |

| Residential Treatment Centers | 36,845 | 11.3 |

| Other Specialty Mental Health Providers with Inpatient/Residential Beds | 13,389 | 4.1 |

| Nursing Homes – patients with diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorders (2019) | 223,917 | 67.1 |

| TOTAL | 411,794 | 124.5 |

In total, the NASMHPD report identified 411,794 inpatient hospital and hospital-like psychiatric beds in America, or 124.5 beds per 100,000 people.

This is now more than ten times as many inpatient psychiatric beds as the “11 beds per 100,000” number that has been most commonly publicly cited.

By direct comparison, then, in 2018, America had more inpatient psychiatric beds than in the 1950s—411,794 beds compared to about 319,000. Accounting for population growth, in the 1950s, there were about 190 state hospital psychiatric beds per 100,000 people while, in 2018, there were 124.5 beds per 100,000 people.

So, there’s been at most a one-third reduction in inpatient bed numbers per capita between the 1950s and 2018. It’s not insignificant, but hardly the catastrophic 96 percent decline that deinstitutionalization disaster stories claim.

This is where Lutterman stopped formally counting. However, he pointed to many more types of psychiatric beds where the numbers were difficult to quantify, but likely very substantial. One of these was category 2, community residential psychiatric beds—and wherever we can find numbers for them, they are revealing.

What community residential psychiatric beds are and why they’re important

Providing long-term residency, with ongoing psychiatric care and support with daily living, was a key role that state hospitals played for many people in the 1950s—and, as discussed extensively in all four reports, moving those patients into community-based residences was a primary goal of deinstitutionalization.

Today, such residences can include, for example, publicly funded private or state-owned small group homes, large congregate care housing, independent-living or assisted-living facilities, supportive housing, government-subsidized apartments, and so on. When these are tailored and funded as psychiatric beds, residents will be getting anywhere from low- to high-intensity monitoring, mental health interventions and treatments, and practical daily supports—often via “Assertive Community Treatment” (ACT) or similar “case management” teams.

Like psychiatric hospitals in the 1950s and today, community residential psychiatric beds can vary in quality—but it’s not possible to reasonably discuss deinstitutionalization without including them.

I asked Lutterman if he agreed it was reasonable to say that, to get an accurate total count of psychiatric beds and to compare today with the 1950s, community residential psychiatric beds must be included. “It is,” Lutterman answered. “The question is, how to get that number?”

Community residential psychiatric beds are not nationally tracked. And depending on the type of facility or residence, Lutterman explained, it may not be licensed by any government agency at all. It may be owned or rented by the client/patient or a private company rather than a public agency, and the housing subsidies, psychiatric services, and supports may be coming through any of a variety of funding streams at local, county, state or federal levels.

Consequently, a reasonably functional “continuum of care” and plan for addressing bed shortages in any community would require having a centralized, frequently updated listing or data repository of currently available beds of all types—yet stunningly, few states have them. In 2019, SAMHSA and the NASMHPD launched a collaboration to help states begin building electronic registries of psychiatric beds. These efforts are still nascent in most states, though.

I found five states that were able to provide what appeared to be reasonably organized and reliable data on community residential psychiatric beds.

Counting category 2: Numbers of community residential psychiatric beds

Connecticut has a bed registry dashboard and New Jersey provided data showing, respectively, about 29 and 39 adult community residential psychiatric beds per 100,000 people in those states. Maryland provided a list that identified 46 adult beds per 100,000 population. However, it became apparent that these were likely low-end, partial numbers, when I found states with more comprehensive tracking of other common types of beds as well—notably, these are the two states where the public clamor about alleged bed shortages has been the loudest in recent years.

The New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH) data dashboard describes and tracks many types of specialized, supportive community housing for people labeled with serious mental illnesses, including “Apartment Treatment,” “State-Operated Community Residence,” “Supported Single Room Occupancy,” and more. According to an OMH spokesperson, and confirmed in the dashboard, the state “funds more than 48,000 units of housing for individuals with mental illness.” In New York, these add 246 adult community residential psychiatric beds per 100,000 people.

In California, the state’s community bed tracking is poor, but it does carefully track its primary community-based psychiatric support system, called “Full Service Partnerships” (FSPs). As of 2021, there were 71,384 people enrolled in FSPs. These programs provide housing as needed and “intensive” psychiatric treatments and other supports for people who are labeled as having “severe mental illness” and at risk of homelessness. According to UCLA’s Sam Tsemberis, who has studied FSPs, these people are typically getting housed in unlicensed, subsidized locations like apartments, rooming houses, and independent living facilities—but, he estimated, as many as 15-30 percent of clients remain essentially unhoused. So FSPs represent closer to about 55,000 beds or 141 community residential psychiatric beds per 100,000 people in California.

About one-third of California’s FSP clients are children and youth, of which many are in foster family homes—a reminder that all states also have community-based residential psychiatric beds in their foster-care systems. A recent study found that, in 2016, some 35 percent of children in foster care were also getting psychiatric care. That same year, about 374,000 children and youth in total were living in group or family-style foster homes (as distinct from hospital-like foster-care institutions). This would then comprise about 131,000 community residential psychiatric beds, or 40 beds per 100,000 people.

In all five of these states, the psychiatric bed count now surpasses the average number of beds per 100,000 people in the 1950s. Before we do a complete tally, though, it’s important to briefly mention some of the other beds that are still missing from the count.

Large numbers of other inpatient and residential psychiatric beds

There were other major types of beds that were not included in Lutterman’s counts because he couldn’t find sufficiently clear numbers for them. In some cases, there were also questions as to whether the beds should “appropriately” be counted as psychiatric beds. Here, the lack of standardized definitions for what constitutes a “psychiatric bed” becomes relevant. For example, many people today get involuntarily psychiatrically detained in hospital emergency room beds for significant periods. Yet some might argue that emergency room beds shouldn’t be counted, because chaotic emergency departments are inappropriate settings for psychiatric care. But by that logic and standard, we’d have to exclude any “inappropriate” facilities from these counts—starting with the many reportedly decrepit, overcrowded, chaotic, abusive state hospitals of the 1950s.

With that in consideration, these are some of the other major types of public beds earmarked today for people labeled with serious mental illnesses that have not yet been counted (see the Appendix for more details about these types of beds and where the estimates come from):

- Many beds for children and youth in inpatient-like residential psychiatric facilities (as distinct from family-style foster homes) exist outside common tracking systems—including in the so-called “troubled teen industry” and out-of-state institutional foster-care settings. This could be another 158,000 inpatient-residential psychiatric beds.

- In prisons and jails, there are both formal inpatient psychiatric units and the equivalent of residential psychiatric beds—together, these appear to comprise about 288,000 beds.

- “Scatter beds” are general beds in community hospitals that sometimes get used for psychiatric care. These beds hosted about 121,000 patients in 2014.

- Many mental health visits to hospitals, voluntary and involuntary, result in people getting “boarded” in emergency room beds. Boarding is usually defined as periods lasting from six hours to days, weeks, or months—already in 2008, this comprised 1.7 million patients annually.

- An unknown percentage of some 988,000 people in nursing homes diagnosed with either depression or anxiety disorders or both may actually be ordinary psychiatric patients (without dementia or debilitating physical conditions). Even a low percentage could represent a significant number of beds.

Getting to the totals: Adding inpatient and community residential psychiatric beds together

Based on the national averages for inpatient beds from the NASMHPD reports, and the other data gathered, we can now do a final tally (see the table below).

In America’s state hospital asylums in the 1950s, there were about 190 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people. Today, there appear to be between 193 and 410 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people. That’s anywhere from slightly more beds to more than two times as many beds per capita as existed in the 1950s. Adding in the best estimates for missing child and youth beds and prison beds, the number today is between 328 and 545 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people—approaching three times as many psychiatric beds as existed in the peak era of state asylums.

If we had reliable ways to calculate for the number of scatter beds, missing nursing home beds, and 1.7 million or more psychiatric patients in emergency rooms each year, the total might skyrocket beyond what existed in the 1950s.

| National-Level Data (from various years) | |||

| Type of facility or bed | Source of data (see Appendix for more details) | Known or estimated number of beds | Beds per 100,000 population |

| Inpatient psychiatric beds | (NASMHPD Report up to 2018) | 411,794 | 124 |

| Community residential psychiatric beds for children and youth in family foster-care | (HHS AFCARS and Keefe study of 2016) | 131,000 | 40 |

| Community residential psychiatric beds | (state-level bed numbers in 2023) | (see state-level bed numbers table) | 29 – 246 |

| Subtotal | 193 – 410 | ||

| Additional inpatient-residential psychiatric beds for children and youth | (est. 158,000 long-term patients annually in 2008) | 158,000 | 48 |

| Prison and jail inpatient psychiatric unit beds and residential psychiatric beds | (32,000 California patient-inmates in 2016 extrapolated nationally) | 288,000 | 87 |

| Inpatient scatter beds in general hospitals | (est. 121,000 patients annually in 2014) | ? | ? |

| Nursing home beds for people labeled with depression and/or anxiety disorders | (unknown percentage of 988,000 beds in 2018) | ? | ? |

| Emergency room beds | (1,700,000 visits/patients annually in 2008) | ? | ? |

| TOTAL | > 328 – 545 | ||

| State-Level Data (2023) | ||

| Public community residential psychiatric beds by state | Number of beds | Beds per 100,000 population |

| Connecticut | 1,025 | 29 |

| New Jersey | 3,546 | 39 |

| Maryland | 2,829 | 46 |

| New York | 48,000 | 246 |

| California | 55,000 (minus unhoused, includes children) | 141 |

There are still many estimates and gaps in these numbers. Yet, at the very least, it is abundantly clear that the dominant narrative is completely misleading.

So, what does it all mean?

America’s expanding systems of psychiatric coercion

The dominant narrative has long stated that America has 96 percent fewer psychiatric beds than in the 1950s which, combined with a desperate lack of funding for community beds and services, has led to legions of untreated, seriously mentally ill people “falling through the cracks” of the system and ending up homeless or in prisons.

This deinstitutionalization disaster story has been extremely effective for generating public support for increased mental health funding and expanded coercive interventions, while excusing the system’s every visible, chronic failing. It’s also given conservative and liberal politicians and journalists alike a simplistic, convenient narrative that can, at will, divert criticism away from innumerable other issues and policies that are worsening inequities, injustices, and violence across society.

This dominant narrative is so popular, even the mainstream organizations that have helped debunk it seem reluctant to let it go completely. Neither the NASMHPD, SAMHSA, nor the APA have been vigorously promoting the true bed numbers; worse, to varying degrees, their reports all partially disguised them. For example, the APA report acknowledged that state hospitals historically served large populations of non-psychiatric patients—and then completely ignored that fact in its own psychiatric bed-number calculations and comparisons. The true state hospital bed numbers are clearly presented in Lutterman’s calculations and discussions—but appear in none of his more visually prominent bed-number comparison tables. Though all four reports emphasized the immense growth and central importance of community residential psychiatric beds in the continuum of care, none of the reports included any attempts to estimate and add in their numbers. Treatment Advocacy Center itself was a co-author and centrally involved in a related 2017 NASMHPD report that drew on Lutterman’s numbers; nevertheless, TAC has not revised its own issue briefings or reports about bed declines that include only the misleading numbers about state hospitals.

Nevertheless, the real data exists, and reveals a very different reality from the dominant narrative.

Overall expenditures (including public and private insurers) on mental health in America increased from $32 billion in 1986 to $186 billion in 2014. Even adjusted for inflation, that’s approaching a tripling in funding. (And it doesn’t include substance use treatment beds and services, which also ballooned.) Compared to the 1955 budget of about $364 million for the psychiatric patients in all state and county hospitals, the increases are even more staggering: By 2014, America’s population had doubled while its inflation-adjusted spending on mental health services had gone up 58 times.

In tandem, where comprehensive bed numbers can be found, there are up to two times or more psychiatric beds per person as existed in the 1950s—and most of these beds can or do involve coercive care.

Involuntary psychiatric detentions in inpatient facilities have been rising dramatically. For example, even with only partial data since 2010, UCLA researchers recently found per-capita detention rates across 22 states rising at three times population growth. At 357 per 100,000 people, the U.S. detention rate is double, triple, or many more times the rates documented in the U.K. and comparable Western European countries. Where older data can be found, such as in Florida, these upward trends have been going on for decades.

Meanwhile, many community beds are linked to ACT or similar case-management teams. As I examine in my book, even when they’re not administering forced drugging through court-ordered guardianships or Assisted Outpatient Treatment, surveys show ACT teams still tend to be highly coercive, frequently pressuring clients to take psychotropics and getting them kicked out of housing or involuntarily hospitalized if they don’t comply. In California, for example, a study found that the majority of FSP clients must comply with treatments in exchange for either the supports or housing or both, and a report to the state legislature predicted that California’s new coercive CARE Courts will dramatically increase the number of people in FSPs. Research in other states has also shown that the majority of people accessing voluntary outpatient services have experienced threats to remain treatment-compliant or risk losing their housing, income, or other supports.

It appears that there’s a “shortage” of psychiatric beds and involuntary treatment in the same way some people argue that there’s a shortage of prison beds in the world’s most carceral nation. A more reasonable descriptor might be “overloaded.”

Every year, ever more people are being channeled, voluntarily and involuntarily, towards psychiatric diagnoses and interventions. Today, more than 8 million Americans are receiving some level of care in America’s public mental health systems—colossally dwarfing the numbers getting public mental health care in the 1950s. Yet the numbers keep rising. Evidently, many of these patients are not improving—or may be worsening, as mounting evidence suggests, from long-term iatrogenic impacts from treatments—and are then not able, or not allowed, to leave their psychiatric beds behind.

Arguably, many of these people would be better served with more affordable housing, higher social security payments, social supports without psychiatric coercion, less aggressive nuisance-policing, improved work conditions and opportunities, different approaches in schools and foster care to distress and disruption, helplines that don’t initiate involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations, and equity and justice advances in society. Instead, the mental health system is being pressed to “solve” the impacts of innumerable social problems far outside its capacity—and further increasing the reach, frequency, and intensity of psychiatric cajoling and force appears to be the primary tool in the toolbox.

Ultimately, rather than the common characterization of a desperately underfunded, threadbare mental health care system that’s been shrinking since the 1950s and where practically no one gets subjected to involuntary treatment anymore, in fact, America has massive, expanding systems of psychiatric coercion threading their way throughout its communities and institutions.

Even in the APA publication Psychiatric News, psychiatric historian Jeffrey Geller similarly described so-called “deinstitutionalization” as instead a nearly all-pervading “transinstitutionalization” from asylums to a plethora of smaller psychiatric-carceral facilities and coercive community beds and services. Among people labeled with serious mental illnesses today, wrote Geller, the only ones “who may be totally unfettered” from psychiatric coercion are “the homeless.”

In similar recognition of this reality, after extensive consultations with persons with disabilities, the 2022 “Guidelines on Deinstitutionalization” from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities declared that, “Housing should be neither under the control of the mental health system… nor conditioned on the acceptance of medical treatment or specific support services.”

Moving ahead, then, let us at least accurately describe what has been happening: America’s mental health system has never had more funding, more psychiatric beds, or more coercive treatment—and to the extent the system is failing, THAT is the approach that is failing.

***

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from The Thomas Jobe Fund.

***

Appendix: Sources for Estimated Numbers of Other Types of Beds

Below are explanations and reference links examining estimates of the numbers of beds in some of the other main types of inpatient and community residential psychiatric beds that were left uncounted in the NASMHPD, SAMHSA, and APA reports.

Child and youth inpatient and residential beds

NASMHPD report author Ted Lutterman’s count included about 42,000 children and youth he found in inpatient psychiatric facilities on a single day in 2018; however, he described and confirmed to me in discussion that many other child and youth psychiatric beds likely exist outside common tracking systems—including in the so-called “troubled teen industry” and out-of-state institutional foster-care settings. Indeed, in an estimate still widely cited today, a 2008 Government Accountability Office (GAO) investigation found 200,000 children and youth in such inpatient-like residential psychiatric institutions receiving federal support, plus an “unknown number” placed “by parents or others” in psychiatric facilities that were often doubling as boarding schools, academies, or boot camps. Because these are residential settings, stays are typically for long periods—so if there were in fact 158,000 or more missed patients in Lutterman’s count, the number of missed beds might be equal to that or more.

Scatter beds

About 80 percent of general hospitals—over 4,000 hospitals—do not have specialized psychiatric wards, but do have “scatter beds” for psychiatric care. These are general beds that sometimes get used for psychiatric care. No one tracks these, but a 2010 study cited by Lutterman estimated a significant 6 percent of all general hospital psychiatric patients stay in these beds—by 2014, that would have been about 121,000 people yearly. Some older studies put the estimate five times higher.

Other nursing home beds

The numbers of nursing home beds holding people diagnosed with depression or anxiety disorders is between 616,000 and 988,000 (there are probably people labeled with both disorders). Lutterman excluded these people because many likely have dementia or serious physical debilitation—yet there’s no data on what percentage are primarily psychiatric patients, though such patients are frequently placed in nursing homes. Given the large numbers, even a small percentage could be a significant number of additional beds.

Emergency room beds

A reported 70-80 percent of hospitals “board” psychiatric patients in their emergency rooms for hours, days, weeks, or even months at a time. The practice has been growing and, in a 2015 study using 2008 data, 1.7 million psychiatric patients annually were boarded in emergency rooms. Many such patients get subjected to forced psychiatric interventions.

Psychiatric beds in prisons and jails

Lutterman noted that many prisons and jails actually have inpatient psychiatric units, but the numbers are currently unknown. In effect, these are the equivalent of high-security state hospital beds that, from the 1950s until today, have been used for criminal/forensic psychiatric patients. On top of, or including those, there are the equivalent of publicly funded residential (albeit carceral) psychiatric beds. A 2016 lawsuit revealed that 32,000 prisoners were getting regular psychiatric treatment in California alone, both voluntarily and involuntarily, and a 2017 lawsuit firmly established a range of psychiatric services for them. Extrapolated nationally, this could be 288,000 beds.

A brilliant report. Here in the UK we have had cuts in services and general impoverishment scince 2008 but an increase in detention under the mental health act. I also know of people forced to live in privately run “supported housing ” where staff oversee patients to make sure they take there drugs but otherwise ignore them, except to refer back to a psychiayrist if there is a crisis. Private, outsourced hospitals for long term detention also seems on the rise, they have little economic incentive to help people recover. I do not know the figures but perhaps the UK is not far behind the US?

I am reminded of The Inner Level, a book which looks at the psychological impact of income inequality on populations. Its badic premise is that nuroticism and narcisism rise as the difference between rich and poor increase, as does crime and other social problems. The book points out that the USA is one of the most unequal countries in the world and has high crime rates and a very high prison population but the high prison population is not justified on a statistical level, it risies faster than the crime rate. The probable explanation of this is that more unequal societies have harsher judicial systems than more equal ones. Maybe their psychiatric systems are more coercive too?

Report comment

Hi John — I don’t know the numbers for the UK, but I can say that they seem to be similar in Canada (I’ll be writing about that soon), and the UK and Canada have in some ways similar public health and social service systems, with increasing privatization occurring in community systems.

Report comment

I think it’s a succesive stage of capitalism that Marx, I’m no marxian missed: When a great power runs out of foreigners abroad to exploit, they are gonna turn innards/inwards and exploit the locals. Another miss for Marx: When they can’t work, i.e. no labor to exploit, they are going to exploit something else…

Savings are not just made out of money but of “human capital”, social connections, knowledge, culture, institutions, infraestructure, foreign policy weight, knowhow. They are also are Wealth. Like Phineas Phog trying to catch up with India and China, which were already catching up.

And the UK and the USA, as was France and Spain where super powers. Except France and Spain were so before the 19th century, they might have become mainstreamy in a way the UK and the USA could not. No chance of healthy adaptation.

I especulate.

Report comment

John,

What you describe…”I also know of people forced to live in privately run “supported housing ” where staff oversee patients to make sure they take there drugs but otherwise ignore them…” is exactly the kind of facility I was talking about in my other comment. I think there are a lot of facilities like this in the US and they should be part of the tally of psych beds.

You make a very good point about income inequality and coercive and punitive carceral systems. That sounds like an interesting book.

Report comment

The subject is extremely important, as it is used to make political decisions that will impact millions diagnosed with serious mental illnesses. The fears surrounding disturbed homeless individuals causing unsafe streets are currently being exploited to justify coercive measures.

Have you considered presenting this data to newspapers? Would you also consider sharing it with political parties through their party offices?

Without compelling counterarguments and data to substantiate the claim, their ability to act is rather limited.

Report comment

Hi Janne — I’ve been trying to draw more public attention to these numbers since I published my book 6 months ago and, so far, the news media and politicians I’ve reached out to have not seemed interested. I’m hoping that having even more detailed, updated numbers freely available online here may help expand public awareness. And moving ahead, I hope that everyone who reads this article will forward a link to everyone they ever hear mentioning the words “deinstitutionalization” or “bed shortage”!

Report comment

tl;dr: Allocating more money to psychiatric beds, counted or not as such, eventually will make in the long run less money available to pay for such beds. No matter where the funding actually comes from. The pool of available people to pay in taxes/insurance for that decreases over time the more beds there are. It’s not a payment, it’s a negative investment. No payer, let alone one that invests or is actually obligated to invest should do that. If anyone has doubts because of Psychiatry’s promoters, as this Rob Wipond piece more than suggests, just do proper thorough bean counting math.

MIA has been pointing a lot of big yellow arrows for that. This Rob Wipond’s piece here is another big one of those.

So to put it in words Psychiatry’s proponents might understand: If it seems unacceptable to you that some people are on the streets, they overflew from an uncaring system that has more beds and more funding than ever had, even per capita if I understood correctly. And the beds are still, in your mind, unavailable for them. Why is that? Are they burning? something? somepeople?

—

So back then 50s and 60s general hospital beds were counted as psychiatric and now psychiatric beds were counted as general beds (social, assisted, nursing, etc., anything but psychiatric). Hum, interesting, like one cannot, could not, tell the difference at least in the accounting between medical disease and psychiatric disease in a bad way. I don’t believe psychiatric diseases are real, let alone medical. Not denying the suffering though.

—

So all this apparently missinformation, maybe even propaganda, comes from a SINGLE influential individual working in, for, with or on the TAC?. That sounds cultish…

Particularly when considering other reports that tell some folks at the NAMI apparently have very bad opinions of persons imputed MI. When to my mind should know better.

But maybe the deinstitutinalization catastrophe narrative is not that ill-willed, it might be just an attempt to bring back the local state funding into the industry, it’s not, but I was untangling the narrative. Since deinstitutionalization happened if I am not missremembering, because the federal govt stopped paying, and the local funding followed suit. For long term facilities I think, and had to do with how the federal insurance changed it’s paying rules. So they just want to bring the State’s money back! not lock more people up (hahaha).

Hey! it might even pass as caring! like in this imaginary narrative: “Look, eventually the private health insurers are going to stop paying. These people need to be in the hospital, a very long time, sometimes forever. Relatives and ‘caring’ people only have so much money. These people are dangerous. It has happened before, that’s why they closed so many [e]state hospitals, they cut our funding!, they took our jobs! (red faced, a little foamy drool on the left mouth corner, waving hands, finally landing the right fist on the desk). Wait a minute, I got an [convoluted] idea!”. [e] might stand for the superintendents perspective.

—–

In Mexico detox inpatient centers and psychiatric hospitals are regulated differently. The first for most intents and purposes are not, the mexican govn does not even know how many centers there are, or what happens inside them. The second now might become somewhat unregulated, the paperwork to expunge from the regulations some of those institutions regulations has been submitted to the body that manages that kind of regulation in or out from the Law. That could lead to more discretionary public funding to facilities that won’t require “standards”. Cheapening psychiatric care and making it more dangerous than already is.

And it provides the continuity of uncare for people who became addicted because of psychiatric treatment called “self-medication”.

Last/this week, there was a newspaper report that found that people with MI are landing in the detox centers, sometimes for a long time, one of them in there by the social “work” institution (the DIF). And there are some newspaper reports of abuse inside detox centers, very diverse in its form and targets. A minor female even got electrocuted and burned with a taser inside one of them, according to the newspapers. Even “random” executions by the organized crime!.

So I guess the situation sounds similar in the US and in Mexico, just we don’t have a Rob Wipond here, sad for us, sad, sad, sad. And suggests to me the use of mental beds is not for medical purposes and promoted or allowed to grow by the profit motive, with the government’s acquiescence and well, lobbying, with all it involves.

Until a year or two years ago, the I think president of some state psychiatric hospitals in Mexico grouping was forced to step down, apparently after terrible conditions in such institutions and some personal “issues” with staff. She is/was the sister of the owner/founder of the largest generic medications pharmacy chain. She and him is or were also related by family ties to the top leadership, some say “ownership” of one national political party. That party got at some point 3 to 7% of the national vote.

‘ the only ones “who may be totally unfettered” from psychiatric coercion are “the homeless.”’ yeah, that was the reason back when I was young a lot of kids “ended” on the streets, without the psychiatric part. Psychiatrists then as now blamed the children, with the caveat all they had was oppositional defiant disorder and ADHD back then, now, well, diangoses against children have expanded…

In full transparency I am not picking on my govt on this issue, until a very few months ago, it didn’t even knew how many people died because of fentanyl overdoses. Even journalist involved couldn’t find out how many lobotomies are done in Mexico, but they do “know” they are performed at the top neurological/neurosurgical public hospital. And they said are very rare but very useful, said the insiders(!?).

—

But more on topic I expect some policy along the lines: “See how big this problem is!? with ever more psychiatric beds we still need more! Mental illness is a a big i$$ue!”. I can see the red face turning into fear, dispair and more, some may say, propaganda. Even renewed animal spirits.

Eventually private insurers will have to stop paying, they have the data, and they should know better that long run, hospitalization and psychiatrization is economically more expensive at least for THEIR profit motive. For insurers is a BAD investment in the long run, even if at some point they didn’t realized it.

They are gonna run out of people to insure, but hey!, I am worried at the next quarter and it’s bonuses.

Economic irony, allocating paying money to psychiatry actually turns out to be an investment that works against me!. A disinvestment, a negative invesment, not just an expend like electricity and paper insurance forms. People should do their research better, particularly when have big enough data.

But more explictly every kid medicated and/or hospitalized increases the changes he won’t get a salary, even a job, to pay for private health insurance. And maybe won’t pay enough taxes to fund government health care, even become a liability, in strictly economic terms, at some point for the government. Probably not to insurers, that’s an externality that insurers probably know about. “Let someone else pay the cost” especially when it is down the road, LITERALLY.

I wonder if there is a law that forces the government to NOT make disinvestments that look like expenses, or at least to look for those kind of “payments”. Particularly when the govn can’t just invest anywhere it sees fit. It has to leave a lot of [e]state for the private sector. It’s a non communism issue.

If private insurers were not that savy, well…

They are obligated by law to put their money in VERY safe investments, that’s why they are big players in the government bond markets. I wonder if the SEC should look into their disinvestment strategy?.

Or if the govn should look into the future liabilities for the government created by the current charges, current expenses, made to the government by IT being such a big insurer. Hahaha, those two last paragrpahs sounded great in my mind!.

Private insurers can’t even allocate money, AFIO, to the united states stock market, it’s too risky for insurers, per the law.

Unlike some corporations in the past that stopped investing formally in THEIR bussiness doing what their bussiness was about and got some or most of their profit FROM the stock market, oh irony, they were stock markets underperformers, but not disinvestors.

They I imagine might actually have tried to avoid being disinvestors, as bad investors not negative ones, by investing in the rest of the market: don’t put good money into a bad investment, investing good and bad being relative, and a matter of degree, a comparison between available alternatives. Just like buying lemons and oranges, or fruits in general.

Precisely because their investments, in their line of bussiness, didn’t pay as much as the returns said stock market did.

Their bussiness became bad bussiness and they didn’t choose to leave the market and become a simple stock market investor, formally. But according to Rob Wipond the psychiatric hospital beds funding never dried it expanded more than threefold in real terms, so. Or was it 58 times?.

The apparent contradiction might be related to government funding, the government funding market, but I am not so sure about that, since apparently it increased, a lot. Disentangling the narrative. So maybe the funding in relation to the expenses and the return, the profit, is not what it used to be?.

Maybe like good ol’ capitalists they gotta keep growing. Still, professionals in the bussiness are being created every year and they need high paying jobs after all their long, hard, meticulous training. In a free market?. That sounds to me anticapitalistic behaviour to avoid competition from the new generations of psychiatrists.

Or, the psychiatric hospital beds bussiness returns are being eroded by the increased costs that, like in NY and Mexico, is being addressed by changing laws and regulations.

To cheapen the cost of providing the service, just to keep oneself in the market.

Funny in a dark kind of way, in my country even the food safety regulations got “suspended” to address food price inflation, by cheaping the cost of food supply, making more food, unsafer, in theory, available for consumers that couldn’t otherwise pay the increased cost. Somewhat parallel, but maybe convoluted.

Oh! Oh! Oh! I think Mr Torrey actually somehow in MY convoluted mind said that!, that somehow it’s “impossible” to lock people up these days, hence the need for more, new(?!) laws and regulations, at least at states’ level. Yeah, federal regulations might cost too much in a dysfunctional federal congress, per the opinions in the media.

—

And circularly, maybe the New York Government current strategy is a reflection not only on the inefficacy and harmfullness of Psychiatry, but how keep trying the polimorphic tried and UNTRUE eventually will, perhaps, exhaust ANY funding… there will be no one that can pay enough anymore.

From me to people who peddle that recurrent policy/strategy: THE MONEY RAN OUT, OFFICIALY, OF FEDERAL AND STATE FUNDING BECAUSE IT NOT ONLY WAS AN EXPENSE, IT WAS BECAUSE IT WAS A NEGATIVE INVESTMENT, A DISINVESTMENT!!!!.

THE MARKET VOTES WITH THEIR BUYING AND SELLING! YOU BUY LEMONS THEY SELL YOU LIES!.

A Nobel memorial prize was awarded because of that, and I heard it is/was the most beaufifull piece of mathematical economics ever published.

—

This Rob Wipond article strongly suggest to me that even closing psychiatric hospitals and try to allocate “patients in need of psychiatric hospital care” in general hospitals, assisted, nursing, etc., could very well be a betrayal of the spirit of the Convention on People with Disabilities. Since it continues the funding for unacknowledged psychiatric beds in coercive carceral torturant environments, and even worse, it does it by appopriating funding from pools of money that should go into treatment of diseases that actually do benefit from the funding, like money for emergency departments, just to send you home and tell you you had a “bubbu” in your finger, nothing to worry more about.

Psychiatry is like a sucking Hydra…

ABOLISH PSYCHIATRY!. It’s like opioids, just takes a little longer, provides a longer lasting money stream, for more players, not just pharma and docs. Just the building permits, hum… drool… in the 70’s the mob might have had a cut of that.

—

If money start falling from the trees keep shaking the trees until no more money falls, like in Connecticut and New Jersey. Then move to another tree… or better yet! expand, until no more trees are left. Except, it’s not just Newtonian apples that’s falling, it’s people…

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Hi, Rob. Great article. One of the reasons I am so grateful for your book is that I had heard it so many times that I actually believed the myth of decreasing bed numbers. So thank you. As you know, I am very much opposed to ACT. If we’re going to force people into treatment (and I believe the only suitable standard is danger to self/others and/or gravely disabled), they should be allowed to choose hospital or ACT. Many would choose hospital. Having hundreds of mentally stable people hospitalized would not be tolerated by the public yet patients subjected to ACT are often mentally stable but invisible. I had a psychotic break in August 2022 and was hospitalized for 3 weeks. I was an involuntary patient but I was happy to stay and I did quickly recover. Here I am, a *year* afterwards and still subjected to unwanted phone calls and unwanted appointments. It’s infuriating. Community “care” is frightening because it can go on indefinitely. There is no way I could be hospitalized for a year in this condition but apparently being subjected to ACT for a year is okey-dokey. The feeling seems to be “What’s the big deal? We’re letting her live in the community.” Sorry, I’m rambling but I think you catch my drift.

Report comment

Except some folks prefer prison over the street, there is food and blankets. And other folks prefer prison over the hospital. So ACT over the street? dunno. But some folks have spoken: some prefer the stree. Some prefer other city without ACT, to avoid ACT and the street, and the prison and the hospital.

And perhaps that’s why they brought psych treatment into the prisons in such great numbers: so that people actually, unofficialy prefer the street.

I guess at some point people are going to prefer Canada, and that’s why Canada is becoming more hostile toward MI. And the delay in implementing the legislation that well, I’ll leave it at that…

Report comment

After decades of treatment for “severe mental illness” that left me broken and alone (social death is real), I wound up, in my late 40s, in a “supportive housing” facility run by Mental Health America. I realized after a few months that this was not a place to “stabilize”, “get back on my feet”, “develop a support system”, “return to the work force”, or any other cliche that’s fed to people in those circumstances.

It was a place where the main objectives of the staff seemed to be keeping people med compliant (we were required to visit the staff office at appointed times to be given our medication under their supervision), and keeping “the mentally ill” corralled in one place. Most of the people who lived there had been there for many years.

In concert with the abusive local hospital, the dismal state mental health outpatient facility, and the fascist local police department, all of us were kept in check. We were throwaways. The facility was in a residential neighborhood but as far as I could tell, the neighbors resented our presence and kept their distance.

After a year, during which I complained too much about things like being robbed on a daily basis by my roommate, I was kicked out for being “too high functioning”.

If this type of facility isn’t included in the count of psychiatric beds, it should be.

Report comment

Hi Kate — I believe that general type of facility is captured in the community residential bed numbers for California and New York that I got, but not anywhere else. What you are describing is one part of what appears to be vast but largely invisible networks of community coercion around the country. If you might like to talk more sometime about this facility and your experiences in it, please feel welcome to reach out to me through my website.

Report comment

Thanks very much, Rob. I’ll do that.

Kate

Report comment

KateL,

Your level of intelligence too threatening for most of the people who work in the “mental health” field.

Report comment

Thank you, Birdsong. 🙂

It does seem like people with intelligence and who question authority present a problem for people working in mental health, particularly in lower income environments like the supportive housing I was in.

(Of course, the system is well prepared for these troublemakers and has an arsenal of labels and tactics at the ready to shut them down.)

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that some (and maybe more than some) “mental health” workers get a perverse pleasure from using their labels and tactics (i.e., manipulation and coercion), especially on people who don’t have the resources to defend themselves. It must be a great place to work if you happen to have an unusually cruel and petty nature, (imo).

Report comment

A medical director at a top private hospital here where I live told me: “They like to be where the meat is.” He mentioned that they didn’t have private paying jobs.

So here where I live who is sadistic and have no paying private jobs among phyiscians?

In those days I had an income in the top decile. So against me they tried to satisfy their need of suffering and their want of money…

Report comment

Rob,

A thank you for highlighting the problem with the conservatorship contracts that psychiatry and psychology too often utilize. And for pointing out more of psychiatry’s lies.

KateL,

If you can believe it, an American psychologist actually told me that social workers should have the right to force neurotoxic poison the best and brightest American children, “to maintain the status quo.” So, indeed, intelligent people do, in fact, threaten the “mental health professions.”

But I do have a hopefully (it’s still early) way for people who want to help a family member who is dealing with a drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity manic psychosis, if the situation is dangerous enough that you do need to take him/her to the hospital.

A large, male, loved one was taken off of two heart meds recently, since they now have – only a moderate drug interaction, but it should be a major drug interaction, warning – that those two drugs have a 10% chance of causing kidney failure.

His doctor was right to take him off the meds, however she should have likely weaned him more slowly from the meds. And I will say, I don’t blame his doctor, since I had checked into the drug interactions of the meds, when he was put on them, and I’m pretty certain that drug interaction was not listed in drugs.com at the time.

Nonetheless, we had to take him to the hospital, due to a first ever manic psychosis. Normally, this would result in a bipolar or schizophrenia diagnosis, and a lifetime of neuroleptics.

But I explained to his nurse and the admitting doctor, that we had a family history of very serious adverse reactions to the anticholinergic drugs (which includes both the antidepressants and the antipsychotics).

So they put him on a benzo, which I agreed was needed, but I did explain I knew the benzos were very addictive, so three days was about all I’d like to see them administer that drug.

Three days later, he is no longer manic or psychotic. He was let out of the hospital with a misdiagnosis of alcohol abuse, which my loved one didn’t like, because he says he hasn’t drank much in the last month – and I was a witness to that. But I told my loved one, that that is a much better misdiagnosis to get, than getting one of the other psychiatric DSM stigmatizations.

It’s always about blaming the patients, instead of the doctors and drugs. But it does seem that a brief course of benzos does work to calm, and hopefully heal, a patient who was dealing with – what seemed blatantly obvious to me, albeit with non-psychiatric, but also, petroleum based pharmaceuticals – to be a drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity induced manic psychosis.

Report comment

Good thing for him you were around!

Report comment

You’re most welcome, KateL 🙂

Report comment

Same system in the UK. Run by private companies, ie outsorced. The one a friennd in was short of money so they sold the house and moved him across town thus disrupting his relationships. Another person I know was living in so called supported living where they put in CCTV to try and stop residents smoking cannibis.The residents understandably saw it as an infringement on their privacy.

Report comment

Very well done, Rob. Thank you for keeping at this seemingly hopeless task of getting people to notice what’s actually going on.

Report comment

Like all myths, deinstitutionalization serves a political purpose. Starting in 1952, antipsychotics, called psychiatry’s third revolution, were supposed to lead to the emptying of America’s large asylums. Thorazine and other drugs were supposed to make it possible for the so-called mentally ill to live outside these institutions. Community psychiatry was invented in the early 60s to take their place.

But as Bob Whitaker has repeatedly documented, antipsychotics did not make things better; they made things worse. So the mental health movement had to come up with a narrative to explain their dismal failure.

The failure of deinstitutionalization became that narrative. Psychiatry, which had claimed the new drugs would allow for the decrease in large asylums, now reversed course and claimed that it was wrong to close them down and allow the “mentally ill” to go on “Rotting with Their Rights On,” in the title of a 1979 article by Paul Appelbaum and Thomas Gutheil.

Thomas Szasz, who in the 1960s led the charge against involuntary treatment, was given the false moniker of “the father of deinstitutionalization.” He had long argued that involuntary commitment violated numerous Constitutional amendments, and was equivalent to kidnapping, false imprisonment, and torture, and its victims should be allowed to sue for damages.

In order to justify the continuation of coercion and force, the mental health movement labeled Szasz and others as cold and uncaring for their refusal to allow the state to provide “treatment” involuntarily to those who were “in need” and who were unaware of their mental illness. In this narrative of their own making, psychiatrists were of course the good guys, and those opposing them were the bad guys.

Rob Wipond has done a great service in exposing these lies. The mental health movement has been one of the most successful social movements in America’s history. So much so, that most people remain unaware there even is such a movement. Its ideology has spun a huge web that reaches into every aspect of modern life. It is going to take a sea change to take it all apart.

Report comment

But it comes from the 19th century AFIR, social hygiene, anthropology, ethnology with derogatory perspectives, prohibisionism, racism, mysogyny, etc.

Only tempered byt the WW2 atrocities, in the US.

Japan, Korea, UK, etc. went the same way.

Latin america from the 60s to the 90s, used psychiatry for the same purposes. The stolen children from “reds” who had “inferior” genes, that sometimes ended adopted in Sweden!.

Franco’s spain and the infamous psychyatrist Vallejo…

Which reminds me there is no big list of infamous psychyatrists and what they did: Ewan Cameron, William Sargant, Lauretta Bender, Antonio Vallejo Najera, Walter Freeman (not a psych), etc. But there are lists of infamous serial killers etc.

Report comment

That’s a great point. There should be a website, at least, with bios of all of the most infamous psychiatrists, along with their crimes against hum–er, treatments. Maybe a deck of cards.

Report comment

E. Fuller Torrey should be at the top of the list.

Report comment

“Latin america from the 60s to the 90s, used psychiatry for the same purposes. The stolen children from “reds” who had “inferior” genes, that sometimes ended adopted in Sweden!.”

Could you provide a source for this? I can’t find it by search.

Report comment

Well, I could search for them in my archives. But it was published either in the NYT, the Guardian or some article pointing them from there.

The case I remember is from Bolivia if I am not misremembering, then kids were sent to Sweden. And decades latter some kids wanted to know their birth parents.

There were some allegations of collusion from Swedish consulate/embassy, but apparently it was corruption from hospital personel: doctors, nurses and even nuns.

And I think in Franco’s spain was similar. I think I read that in the Guardian.

Recently in the news is the reunion of a grandson fo the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina. Those cases have streams of artciles.

But here, second search hit:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jan/26/chile-stolen-children-international-adoption-sweden

And maybe the question is about the link between mental illness and stolen babies, well even Salvador Allende was an eugenist, as was the infamous Salvador Vallejo.

For that link I cannot provide a single reference, it’s more of a collage of readings on latin american history. But maybe Salvador Vallejo could provide a good lead, I kind of remember reading that somewhere.

I haven’t read this one but:

https://time.com/5321938/spain-stolen-babies-franco-trial/

This one I’ve read:

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/27/magazine/spain-stolen-babies.html

This one I haven’t read, its from the Netherlands:

https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/22/sweden-investigate-illegal-intercountry-adoptions

Maybe it is the 60’s and 70s statement? or the only latinamerica?

The Netherlands report quoted from HRW seems to provide references to Brazil and Colombia starting in 1967, so that might be a better? starting point?.

Report comment

Perhaps this is a confusion of the abuses in Chile with those in Francoist Spain?

The Chile Guardian article is about social and medical workers that “sold” children to adoptive services in Sweden with coercion, sometimes without the mothers’ consent. “These adoptions were part of a national strategy to eradicate childhood poverty, which the military dictatorship hoped to accomplish, in part, by removing deprived children from the country”.

It says Franco confiscated the children of political opponents he imprisoned or executed and regime loyalists adopted them.

https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020155

“In 1938, Franco instituted the Gabinete de Investigaciones Psicológicas de Inspección de Campos de Concentración de Prisioneros de Guerra (“Cabinet for Psychiatric Inspection of Concentration Camps of Prisoners of War”) and appointed Vallejo-Nágera to lead it.”

Vallejo who I just learned was a psychiatrist with eugenic theories. As you said, “The stolen children from “reds” who had “inferior” genes”, and it says Vallejo considered the Marxists (reds?) to have an intellectual disability. Maybe his ideas spread to LatAm though?

Anyway, thanks for the links, I hadn’t heard of this before.

Report comment

To Garret:

Sorry, but as the Groucho said: “I insist there is a resemblance”, I remember there were cases from Bolivia, but as pointed I might be confused, happens, frequently.

Thanks.

Report comment

Yours is a very cogent reply. I internalized psychiatric dogma after my institutionalization. Reading Szasz and articles from Ethical Psychology and Psychiatry (not the exact name of the journal) helped me to see through the smoke screen.

I have seen how psychiatry has encroached on our society through my work in public schools, Job Corps and various non-profits. I’m sure readers are aware of the psychiatric drugging of our youth. Rob mentions the role of nursing homes in the equation. Similar to nursing homes is community care for the developmentally disabled. It was very common at our agency for my clients to be taking psychotropics.

Report comment

My reply was for Keith.

Report comment

The last thing the mentally ill need is more commitment laws and more involuntary state hospital beds. Anyone who knows anything about the abuses of the old state hospitals, knows that we need to go in another direction. My own experiences in the state hospital is one such example of what not to do (“State Hospital Memories, 2023; Committed at 16, 2020, MIA). If a large hospital of any kind is planned like Dr. Torrey seems to suggest, it will be so expensive to operate that it will soon descend to the snake pit of old. Why not look elsewhere for better and cheaper solutions? The federal government is now offering money for short-term stabilization centers, and there are ways of handling those in mental health crisis. In Eugene, Oregon, for instance, they have a long-standing mobile crisis unit which comes out to those having difficulties. https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/05/us/cahoots-replace-police-mental-health-trnd/index.html

Report comment

One of the big criticisms against, and reasons for closing, the asylums was that patients experienced so much harm out of the eye of the public. The fact that there wasn’t proper or public oversight of these places allowed for them to become places where those who were meant to be helped — or at least cared for — experienced harm.

In light of that, it’s interesting to think about how much harm still takes place with no proper oversight, whether in short term facilities, in therapy offices, or even inside the bodies/brains of patients being treated for mental illness.

No one actually sees the damage that neuroleptics do to the gut, brain, metabolism, heart, etc of a person being made to take these drugs. No one actually witnesses the impact of an ECT treatment on brain circuitry. All of this harm takes place within the body of a patient. So the problem of lack of oversight hasn’t been solved.

Report comment

Of course, the fact that “treated” people die one to two decades earlier than expected IS a bit of a clue…

Report comment

“On average” some folks die during hospitalization, or “shortly” afterwards. They don’t get their lives saved by hospitalization but shortened by it.

Now, that I think about it. Maybe the mortality rates studies are biased by not counting the mezzanine? i.e. hospitalization. With the caveat most “diagnoses” are done in hospital for some folks, or “shortly” after discharge. Or at least for those “likely” to die sooner.

Maybe most or all studies are done are after hospitalization. Discounting the years lost of mostly young men, maybe mostly non-white that die in the FIRST hospitalization. Given the mental health uncare disparities.

Which somehow obviously would be more evident among females since they live longer. And I think against females neuroleptics and ECT are used more often.

Report comment

If you are a danger to yourself and others you NEED coercive treatment. Duh.

Report comment

I don’t consider this obvious. A person may need PROTECTION, yes, and others may need protection from THEM, but why does “treatment” in the form of enforced drugging necessarily emerge from feeling angry or confused or despairing? How about giving folks a safe place to calm down and some sane people to talk with if they want, plus some food and sleep and the like? Why start with forced drugging as the only “answer,” especially when we see how poor the outcomes are for those experiencing such “treatment” in the long term?

Report comment

Dr. Torrey is one of the most compassionate men I know. I met him twice at schizophrenia conferences put on by NAMI and Columbia University Presbyterian Hospital in NY. His sister has schizophrenia, by the way. His book, Surviving Schizophrenia, did indeed help many families survive schizophrenia. I asked him and Dr. Lewis Opler at a question session, “Is tough love appropriate to use on family members with schizophrenia?” They said NO.

Report comment

When people are psychotic, kindness and nurture don’t work. Drugs are better than a strait jacket or padded cell. Not to say people should be over-drugged or forever drugged. There is no perfect solution, it is horrible to have to go through. A psychiatrist at one schizophrenia conference said neuroleptics are like a shotgun, hitting parts of the brain they shouldn’t, that’s what causes side effects. Keep developing better drugs that only hit where they should. But we don’t have them yet! If people can’t stand neuroleptics, they turn to street drugs or alcohol. Which kills first?

Report comment

It’s worse than that, Molly. They don’t know what they should be aiming at. The drugs hit parts of the brain they ARE intended to hit as well, and THOSE parts of the brain get broken down and stop working properly, too. They’re not quite shooting at random, but the targeted parts of the brain do not heal under their attack. And destroying them isn’t good for the brain, either. It is a poor solution.

Report comment

Neuroleptics kill first. And are a lot less fun.

Report comment