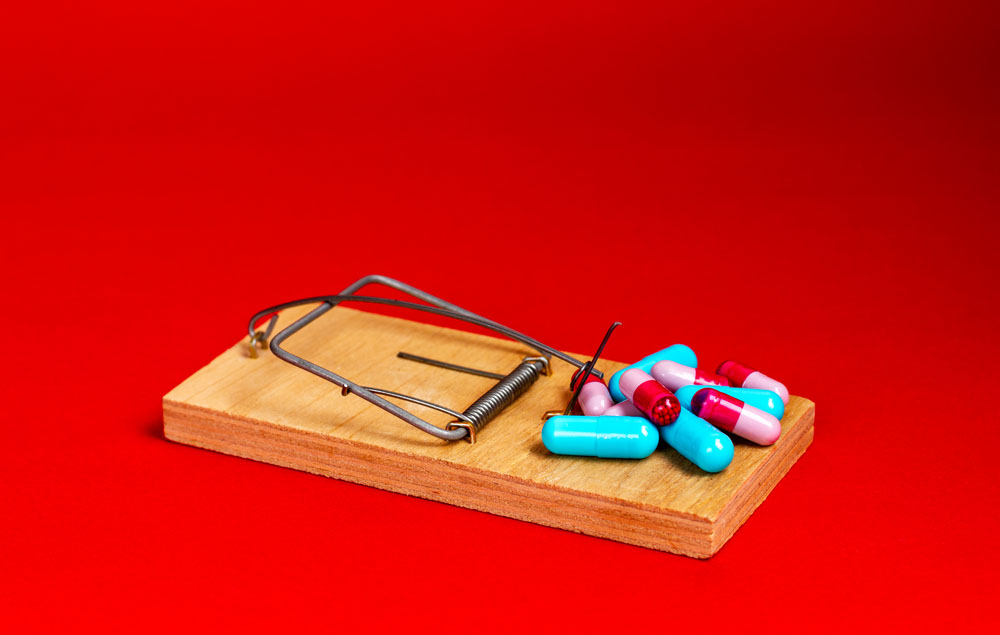

It was about 10 years ago I wrote in a MIA blog post that if I thought that it was possible, I would have opened a string of clinics all over the country to help get people off of antidepressants. Unfortunately, the problems that sometimes occur when people try to stop an SSRI antidepressant are still much more severe and long-lasting than the medical profession acknowledges, and there is no antidote to these problems. My blog post goes on to explain this in more detail.

As I wrote in a blog on August 2020, my seeming pessimism was commented upon by MIA readers, and I took the criticism to heart, and renewed my efforts to help people to stop SSRIs. In this blog I discuss the issues related to antidepressant withdrawal, but most importantly I write that there is no way to predict who is going to develop the most severe problem, akathisia, and it’s cousin, late onset akathisia that occurs months after successful tapering. My opinion is that these problems do not result, as most people think, from tapering too fast. In my experience, it happens even with very slow tapering. It is unpredictable. As a consequence of tapering, akathisia is devastating. I do not think that anyone who has not already experienced akathisia can realistically be prepared for this possibility through informed consent; it is simply too uncomfortable to be fully imagined in advance. This is what keeps me from my string of withdrawal clinics.

As I wrote in a blog on August 2020, my seeming pessimism was commented upon by MIA readers, and I took the criticism to heart, and renewed my efforts to help people to stop SSRIs. In this blog I discuss the issues related to antidepressant withdrawal, but most importantly I write that there is no way to predict who is going to develop the most severe problem, akathisia, and it’s cousin, late onset akathisia that occurs months after successful tapering. My opinion is that these problems do not result, as most people think, from tapering too fast. In my experience, it happens even with very slow tapering. It is unpredictable. As a consequence of tapering, akathisia is devastating. I do not think that anyone who has not already experienced akathisia can realistically be prepared for this possibility through informed consent; it is simply too uncomfortable to be fully imagined in advance. This is what keeps me from my string of withdrawal clinics.

Because of the uncertainty, I felt that I could not honestly tell people that I could guarantee that my strategies would safely allow them to stop taking the serotonin based antidepressants, or that they would even be able to stop. The data indicates that not everyone is able to stop. There isn’t data that clarifies how common akathisia and late onset akathisia is in people who stop taking these drugs, but I saw it fairly often. Too often to be able to say that this is very rare and unlikely to happen.

The difficulties stopping antidepressant are summarized by Dr. John Read in a Psychology Today article updated on 9/15/23. In a survey of British antidepressant users, 10% stopped with no major issues, 10 percent stopped with some difficulty, 34 percent stopped with great difficulty and 46 percent were unable to stop despite wanting to. Only 3 percent had been told about the risk of withdrawal effects when first prescribed the drugs and only 8% reported that services have been helpful and adequate to help them stop antidepressants. Dr. Read recognizes the need for greater education of mental health professionals to assist with deprescribing. Forty five percent of patients were told in advance that they can stop in a few days or weeks without problems. Forty four percent were unable to get informed advice about how to safely stop, and 41 percent were told that their withdrawal was actually relapse.

While physicians are largely uneducated, 13 deprescribing services were surveyed to determine common practices (Cooper et al. 3/15/23 PLOS ONE). These services used gradual tapering of medication with smaller reductions as the total dose became smaller (hyperbolic tapering), individualized reduction schedules led by the patient and support and reassurance throughout the process of tapering. These are the most useful aspects of helping someone to get off of SSRIs.

Fundamentally the medical strategy for deprescribing revolves around tapering the SSRI slowly theoretically allowing the serotonin receptors to adjust to the lower drug dosage and ultimately the absence of the drug. However, this theoretical framework doesn’t explain why some people remain symptomatic for years after stopping SSRIs. It also doesn’t explain the many withdrawal and toxic symptoms which are seemingly unrelated to serotonin receptors.

It appears that the SSRI withdrawal problems are more than just the serotonin receptors resetting. One hypothesis relates to the effects of BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is involved in the integrity of the nervous system, including neuronal maintenance, neuronal survival, plasticity and neurotransmitter regulation. Patients with psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders often have reduced BDNF concentrations in their blood and brain. There is research that shows SSRIs enhance BDNF gene expression. Perhaps some of the withdrawal related symptoms relate to a relative lack of BDNF when the SSRI is removed. This might explain why people suffering from SSRI withdrawal find exercise helpful. Exercise stimulates BDNF.

The most elegant hypothesis for the cause of protracted withdrawal symptoms has been proposed by Dr. Healy. He has been able to tie together the myriad withdrawal symptoms, the protracted withdrawal symptoms and PSSD with the concept that the drugs damage the sensory receptors, a neuropathy of small c-fiber neurons. Noting that anticholinergic drugs in a low dose have been shown to promote small nerve fiber ending to regrow, this suggests a possible treatment that promotes a faster regrowth. It is not necessarily an immediate antidote to problems like akathisia, but promises to speed recovery. This hypothesis needs further testing, but explains more of the variety and persistence of withdrawal symptoms than does receptor resetting.

It is heartening that deprescribing SSRIs is becoming more popular, although the emphasis on tapering strategies related to serotonin receptor resetting is clearly only addressing a part of the problem and cannot guarantee that tapering is going to be safe and successful. Except for the in vitro receptor saturation data suggesting a slower taper as the dose is reduced, there is no scientific data regarding tapering strategies. This in vitro data has not been studied to determine how much it correlates with in vivo data. There is no scientific study that programs adding in health promoting strategies such as supplements, meditation, mindfulness and yoga and even psychotherapy can promise a safe and effective withdrawal either.

Tapering carefully is certainly important and makes the process more comfortable, but it cannot prevent protracted withdrawal symptoms and cannot guarantee that a person will be able to stop the drugs or that akathisia or delayed akathisia or other sever and potentially protracted symptoms will not occur. While it is best to stop taking these neurotoxic drugs if at all possible, and what we have to work with right now is tapering strategy, this is far from being the only variable involved and needs to be approached with caution. What is needed at this juncture is solid scientific research to establish a pathophysiology to explain why these severe and persistent SSRI withdrawal effects occur, and to develop treatment strategies—not just tapering strategies—that will address these problems.

Thank you for this sobering yet insightful article. Which specific anticholinergic drugs have been found to be most effective in helping to regrow nerve fibers?

Report comment

“10% stopped with no major issues, 10 percent stopped with some difficulty, 34 percent stopped with great difficulty and 46 percent were unable to stop despite wanting to.”

Considering how many are on these drugs this is a major health issue.

Report comment

Yeah, 20-40% of spanish young adults and around 50% US medical students sounds alarming.

Report comment

Thanks for elucidating the problems with tapering and a possible explanation. I discontinued 4 psychotropic drugs in May 2018, two of which I had slowly decreased over at least a year. I experienced severe post-acute withdrawal for nearly 3-1/2 years afterwards. (I had been prescribed nearly 50 different drugs over a 31 year period by a psychiatrist who had misdiagnosed me.) It was hell. For me, it was hell being drugged (I lost most of my adult life – “numbed & dumbed”.) and it was hell getting off of them. Thanks for sharing this.

Report comment

So, if I am understanding correctly SSRIs produce “prunning” of the input part of the neurons, the dendrites.

And that is similar to what made all the scandal about schizophrenia being a brain disease: pruning of the very, very fine part of the dendrites in some brain tissues/areas.

Latter suggested to have been an artifact of the brain slice preparation that would abhor Santiago Ramon y Cajal.

But, assuming, it was not an artifact, which I don’t believe, SSRIs might promote brain changes that are similar, if not identical as those proposed on the top media, the top, as “biological marker” of schizophrenia?. Or worse yet, assuming, similar to the damage by neuroleptics?.

Which was one of the offered refutations to the prunning hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuroleptic induced, not disease related, at least not directly, i.e. in the abscence of treatment.

Wow, talk about going to the laundromat and ending up being pressed and folded…

Report comment

I think pruning as hypothesis for akathisia might not be that good: Rare folks who start an antidepressant developed sometimes severe akathisia within 4, four, weeks of starting SSRIs.

I think it is too little time for some long term transcriptional alterations, even histone methylation to “kick” in, that could cause “prunning”. Given it’s probably a long term change.

And the unpredictability in time, individuals, circumstances, etc., of it, makes me dubious it’s an anatomical thingy.

Neurological deficits BY ANATOMICAL brain damage occur when 95%, around, of the “neurons” involved are dead. As far as I rememeber. That was the classical description of Parkinsons, strokes and Alzheimers, decades ago AFIR. Hence their irreversibility even under plasticity.

The “subtle” signs and symptoms, hard to distinguish from normal, aging, variations, etc., occured when over 90% of neurons were dead.

But I have an alternate biased hypothesis that could potentially explain the variability in time, within and between individuals:

THE BRAINSTEM.

First, in disclosure, my bias: I think Havana Syndrome is a tardive effect of exposure to psychotropics, covertly, overtly, unrecognized or unacknowledged. Not the effect of an “ultrasonic” ray gun, nor “mass hysteria”.

Now, how and why the brainstem?: many soft, hard to categorize symptoms AND signs, difficult to put in a “syndrome” in neurology are related to the brainstem. Small anatomical lesions there, like in dead neurons, are difficult to study even at 7 Tesla.

Whatever Teslas are available now seems to me kinda irrelevant to SSRI withdrawal, it will not be an anatomical thingy in the MRI sense.

And even higher teslage will be of no use to study the functional circuitry of the reticular formation. It does not work very well even for big, fat, thick fascicles that connect the upper, “human” brain. Dead neurons being absent…

The pathology of the arcuate fascicle in no mental illness as far as I imagine has not been described, and it is thick!. And it probably, most definitively if schizophrenia was a brain disease it would be severely “dysfunctional” in those cases.

To return to topic.

That’s my why.

My how is: probably the brainstem works in many different varied contradictory ways in the course of one’s life, in the course of one’s day.

Precisely because the brainstem is involved in so many vegetative and willing functions, like sexual pleasure and orgasm, it’s circuitry probably fires differently whether one’s riding a bike, hanging like batman from the ceiling, watching a movie, riding a train, driving a car, or having intercourse.

Eating, drinking, laughing, gazing, sleeping, running, walking, showering or just standing will look, to my mind like the old batcomputer in the brainstem: a bunch of light bulbs are on in one situation, off in another, and yet another, and so forth. And a tiny variation even in head posture might change it’s dynamic state.

And it’s current state is probable previous state dependent. Like a classical single tape digital computer…

It’s no mere analogy for me, that could give a stocastical flavor to a terrrible bad outcome, described as side effect. And hard to analyze if neuroanatomy and neurophysiology really haven’t progressed much in describing the circuitry of those “vegetative” very small, but very relevant group of neurons, particularly in the reticular formation.

How would that explain the crossing over into tardive akathisia?: CHAOS theory, dynamical systems.

Sometimes systems start functioning on a different configuration, a different set of “behaviours” connecting inputs and outputs.

A different long term state, kinda of a closed tight, restricted loop of now available functional states, in computational terms.

A new way of functioning starting apparently from small perturbations on an already at tipping point system. What most knowledgeable people call a “crisis”, it could go either way.

And that could explain why akathisia might appear to come from nowhere: it could be a vegetative reponse that comes from a vegetative, unconscious, reticular formation.

Unlike phobias, stress or anxiety that in principle could be modified by the “conscious” brain, extreme responses being absent, no call back to the brainstem, no amplification within it either.

And that could explain why it is confused with “floating” anxiety, they might come from the same part of the brain: the reticular formation.

Now, how my fantasy give anyone experimental hypotheses? Beats me, last time I read about the reticular formation was over 30yrs ago…

But from an armchair neuroanatomy fan with a touch of frustrated mad scientist, it makes sense.

Report comment

Think you are spot-on here …

Brainstem

Report comment

Just ran across this blog and thought I would leave a comment, as I hope it may help.

So I started taking antidepressants in 2011, and basically went through the entire gauntlet of antidepressants. After about two weeks of taking any antidepressants I would begin to have side effects. They ranged from mild to severe, and did nothing to relieve my depression. So after two years of the antidepressant and nothing but side effects, I went cold turkey. Day one off not a problem, as it was until day number five. That’s when the withdrawal hit and at the time I was taking effexor. The withdrawal was unbelievable difficult and many times I wanted to go back to taking just avoid the withdrawal. It took a few month before I felt normal again.

Then in 2016 after having side effects not only to antidepressants, but other medications, it was suggested I get a genetic test done to see how well my body metabolizes medication. Wow what an eye opener that was. I found out that I am a poor metabolizer of drugs that need Cyp2d6 and Cyp2c19, I am also a SLC6A4 l/s meaning I wouldn’t have a good response to SSRI medication.

I don’t think many physicians take that into consideration. So for me the medication would build up to toxic levels and I would suffer from side effects and I believe withdrawal was difficult due to it taking my body a longer time get rid of the medication. Instead they dose every one the same, not knowing how their body will handle it in the first place.

Hope this helps, it helped me understand that it’s not the drug but they way my body handles the drug.

Report comment

I had a reaction to metoclopramide which is also metabolised by cyp2d6. My gene tests were unremarkable. I have to say with the varability in cyp450 genes in the group it’s not the whole story, though may contribute to toxic load.

Report comment

Is withdrawal from SNRI’s the same?

Report comment

It is quite similar, Sarah.

Report comment

I spent 27 years on Paxil and don’t believe tapering will be shown to be an effective strategy. What I found to be helpful were strategies involving nutrition, exercise and mindfulness. I am glad I didn’t taper and although it has been difficult the symptoms I connect to Paxil withdrawal have slowly but consistently improved over time. Like others I believe the best strategy is alternative treatments that don’t rely on medications.

Report comment

Very important insights. Thank you!

Report comment

Stuart, it’s good to hear that you’re still thinking about this.

Unfortunately, none of us can guarantee outcomes from tapering. Very gradual hyperbolic or exponential tapers seems to yield better results in that withdrawal symptoms during the process are milder or nonexistent, but even some people with uneventful tapers may experience a protracted withdrawal condition afterward, or have a mysterious resurgence some time later. And some people find it excruciatingly difficult to reduce the tiniest bit of dosage.

We do need conscientious clinicians to look into treating post-discontinuation syndromes as well as any psychiatric drug-induced neurological dysfunction. Not being a physician, I’m not in a position to do that. I strongly support such efforts. As you probably know, I suffered protracted antidepressant withdrawal syndrome myself for 11 years, and might not be here now if in the last half, I hadn’t been prescribed microdoses of lamotrigine as a crutch to stabilize my nervous system.

On the other hand, I have seen many taper off, feel well, and go on with their lives. On SurvivingAntidepressants.org, we urge people to return and give a retrospective summary of their journeys off drugs, but often they don’t want to rehash a trying time. (Dear reader, if you were a member of SurvivingAntidepressants.org, please do come back and tell us how you’re doing.) However, we do have a collection of successes, including recovery from PAWS and PSSD from all kinds of drugs, not just antidepressants, and tapers that went well.

The history of psychiatric drug tapering is short, sparsely documented, and, until 2019, without a hint of formalization. The dictionary we have of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms, for example, was derived from what we would think of as failed tapers, as the clinical trials in which they were incidental findings utilized abrupt discontinuation or, at best, a jagged taper over a few weeks.

The researchers collated the symptoms they observed, and who knows if the terminology they used was entirely accurate, as we lack language to describe the bizarre symptoms that arise from nervous systems disordered from psychotropic withdrawal.

We can assume those were acute withdrawal symptoms, because the subjects were not followed beyond a month or so. When acute withdrawal symptoms, often quite vivid, abated after a few weeks — as acute withdrawal symptoms from almost all psychotropics do — that was taken as the whole of antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. These studies were also often conducted in people who had been on antidepressants for 6 to 12 weeks, who would be likely to have shorter lasting withdrawal symptoms than long-term users.

Researchers did not think to look for the qualitatively different protracted withdrawal symptoms, because protracted withdrawal was not a thing (though it appeared in Heather Ashton’s work on benzodiazepine withdrawal and has been lurking in addiction medicine for decades).

My guess is those academic psychiatrists were shocked by acute antidepressant withdrawal, but relieved to report (wrongly) that it ended within a few weeks. Those papers about withdrawal were subsumed in the avalanche of paeans about antidepressant efficacy, proving which was the main objective of most of those studies.

(Privately, some clinicians did see protracted antidepressant withdrawal, but this was whitewashed in the two massive “expert consensus” antidepressant withdrawal supplements headed by Alan Schatzberg on behalf of Lilly and Wyeth pharmaceutical companies in 1997 and 2006, respectively.)

So up to Horowitz and Taylor, 2019, what we know about from the psychiatry literature psychiatric drug withdrawal has been based on haphazard, short tapering practices. Over the last 35 years, the lack of clinician knowledge about tapering has doubtlessly produced a very large population of people suffering from acute and protracted withdrawal syndromes from antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs — though most of them probably never named it.

This rate of injury has proceeded through decades of bad clinician tapering advice, and thousands continue to be injured by it. Some develop severe withdrawal syndromes, some of which may be intractable. From the late ‘90s to today, accounts from these protracted withdrawal sufferers have gained visibility on social media. Over the years, they have been seen as patients by people such as yourself and Dr. David Healy.

One might hypothesize that widespread harm reduction tapering would reduce the production of protracted withdrawal syndromes or intractable post-discontinuation effects, but we do not know yet if this is so. The era of widespread gradual individualized tapering hasn’t quite started, so we don’t know how often it is successful and how often it results in iatrogenically induced neurological dysfunction (IND).

Further, and in my amateur opinion this may be quite important – people who are tapering now often have histories of being switched from drug to drug – normal clinical practice – or skipping doses (studies estimate about 50% miss doses) with prior bouts of withdrawal and adverse drug events. Just guessing here, but this cannot be good for nervous system integrity. So, unknowingly, they often start tapering with nervous systems made vulnerable by earlier drug-induced events.

For these people, it may indeed be more difficult to taper. Or it could be for some individuals, the psychotropic drug gets such a grip on nervous system structure, removing it causes major disruption. But from what I’ve seen, compared to abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering seems to provide a safer exit from psychiatric drugs and if there are after-effects, most people tend to slowly recover from them over time. Gradual tapering is a harm reduction technique, not a guarantee of success for everyone.

It’s my dearest wish that physicians take on the responsibility of safer prescribing and deprescribing of psychiatric drugs, while testing all hypotheses of safer discontinuation and treatment of drug-induced neurological dysfunction.

I’ve given this a lot of thought over the years. I acknowledge that outcomes from carefully tapering cannot be predicted, and there is a risk of disaster of unknown probability – but much less risk than from abrupt discontinuation. I don’t encourage people to go off their drugs, but I cannot in good conscience withhold common-sense tapering information that can enable them to minimize or go off. To my mind, choosing to take a psychiatric drug or go off one despite unknown risk is a decision of self-determination, a human right.

Report comment

Alto, I’m glad to see Dr. Shipko is still in the game as well. Your thoughts, and Dr. Shipko’s, on short term vs. long term side effects, echo Cosci and Chouinard 2020.

All of this also speaks to the way we’re approving drugs and doing research– it’s been said before, but is worth repeating: RCTs are simply not appropriate instruments for assessing or measuring harms from psychoactive medication, particularly when combined with self reporting inventories.

For the last 15-odd years, I’ve been most concerned about p-hacking, HARKing, and baroque methodologies, including using assessment instruments as outcome measurements. More recently, I’m also getting a really bad feeling about sample selection, and in the past six months– particularly after reading Cosci and Chouinard– getting a REALLY bad feeling about the painfully short longitudinal snapshot that’s used for most psychiatric drug research.

I always think about Mickey Nardo used to say on Boring Old Man– Rheumatologists and Psychiatrists are the craziest specialists because they study stuff that’s really hard to measure. And while rheumatology research is plagued by some of the same problems, at least they try– there are studies that follow people for 30 years…

Of course, over a few decades, all kinds of confounding variables pop up like mushrooms. It’s worth remembering that while there’s a lot of big Pharma greed at work here, and it’s just as disgusting as everyone says it is– I know marketing folx who got out of the business because it was so ugly, and I worked at a medical PR firm myself, very briefly, right out of college– that’s not the whole story. Research on the harms of psychoactive medication is also really, really hard to do well.

Report comment

Rheumatology also does not deal with people’s character, conduct, personality, mood, behaviour and sanity. Rheumatology diagnoses can’t be used as slurs (at least 99.9% of the time). The outcome of any intervention on a person’s mental health doesn’t simply depend on the drug a person is prescribed.

Say a person is suicidal due to heavy financial burdens, no amount of playing yo-yo with his brain chemistry using antidepressants is going to fix that practical problem that exists in his real life.

Report comment

But we want him to feel OK about being in debt! Don’t want them WORRIED about it!

The goal seems to be Stepford Wives!

Report comment

Just like being indebted to study for clinical psychologist. For then to chase patients with self promoting books, refered or reviewed by forums that are supposed to be critical of the concept of mental illness.

Even non profits might pursue the promotion with links to clear pieces of clinical psychology propaganda.

Maybe with the excuse or justification of “public interest”. For then to disallow with other excuses critical comments of said refered “reviews”. Easy to see the point is to promote when criticism is put up to a “high” bar. Higher than the reviews of scientific articles in some non profit forums…

Money moves the psych world…

Report comment

Whoa! Respectfully and strongly disagree with the first two sentences of your post. Medical gaslighting is a particular problem in rheumatology, and rheum patients are frequently offered SSRIs or other junk meds for pain. This is a huge problem. I was offered Nardil 25 years ago, though that’s an MAO inhibitor, though I never reported any symptoms of depression! Now, there’s a pretty good chance someone will try to get you set up with Lyrica or Cymbalta.

As for the diagnosis, I would argue that Fibromyalgia is used as a slur… or, at a minimum, it’s usually pretty pathologizing. In many medical settings, it’s pretty much like saying, ‘You may have lupus, but that pain you feel all over? That’s the fibro… oh, no, of course it’s not in all in your head, but… well, we’re recommending exercise, CBT and SSRIs!”

However, very much agree r.e. tampering with brain chemistry not fixing practical problems.

Report comment

I did not know antidepressants are used in the context of rheumatology too. Again, if the drugs work to reduce pain in anyone, God bless them.

Also, the example of Fibromyalgia being used a slur pales in comparison to anything in Psychiatry. Almost no one accuses people, friends, spouses, children etc. of having fibromyalgia when they don’t like what they do or want to do away with them (their feelings may in some cases be legitimate, in other cases ill-intentioned). The incidence and scale of using something like fibromyalgia as a tool of gaslighting pales in comparison to psychiatric categorisations. The abuse potential isn’t even close to any of the personality disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders etc. Those literally are directly about behaviour.

Granted, as human beings, it is our nature to categorise things in order to study them or to simply have a shorthand to refer to them. But the categorisations in Psychiatry are insidious and it’s even worse when Psychiatric supporters keep justifying it without giving an inch of space to admit the harms caused by them.

Report comment

Reumathology does have radiographical scales, objective ones based in X rays and MRI.

Symptoms and disability might be somewhat subjective, but the imaging based scales are not.

There are for rheumatoid artritis, psoriatic artritis, osteoarthritis (which is not rheumatological IMO), anomalous cartilage deposition, ankylosing spondylitis, etc.

Maybe the equivocation comes from vasculitis?.

Even CNS vasculitis can be seen now as microhemorrhages in the brain.

Report comment

In psychiatry, both doctors and their blind-follower patients talk about MRIs and fMRIs: “Do you believe in MRIs and fMRIs?”, “You can tell from a PET scan or a fMRI if a person has schizophenia. Such as large ventricles and frontal cortex atrophy” etc.

Except, you know what? 99% of the time they never actually DO any imaging in practice. They make excuses like “invasive and expensive”. How “invasive” is an MRI? You go into a hole and come out of it. Okay, maybe if you’re giving contrast it’s somewhat “invasive”, but it’s no different than taking blood.

What they do is bullshit people by showing images in textbooks and journal papers, but almost never the brain of the person they are treating to the person being treated. If I have COVID, I see the results of my PCR test. Not someone else’s in a journal paper.

I suspect this is partly because (in the case of an MRI) they wouldn’t be able to make out jack-shit and their patients will ask them “well, I seem to have a structurally normal brain don’t I?” and that gives them more power rather than handing it all over to the psychiatrist. Patients are even worse than the psychiatrists sometimes. If anything, they are the ones akin to Scientologists. Cult-like behaviour.

Once again, in no way am I suggesting that people don’t suffer from problems ranging from depression to hallucinations, and sure they have biological correlates (what behaviour doesn’t?), but I’m trying to point out the conman like tactics of psychiatrists and (some) of their patients.

Report comment

These “differences” are AVERAGES – They can never be used to determine if person A “has schizophrenia” or person B does not. There are tons of “schizophrenic”-diagnosed people who do NOT have frontal cortex atrophy. It’s also well known that frontal cortex atrophy and other brain shrinkage can be caused by the antipsychotics themselves. PET and f-MRI studies are absolutely useless in “diagnosis.” And of course, this must be the case, because there is no reason to believe any 5 people with the same “diagnosis” have the same kind of problem or need the same kind of help.

Report comment

Fair points– and most rheum disorders have some kind of antibody signature in the blood as well. That’s very different from depression, anxiety, etc., where it seems like there’s never any biomarker, despite the claims we’ve heard. I did not mean to set up a false equivalency, and I can see why you’d assume that I was.

I think Nardo was talking more about the symptoms and disability– and that’s the part that’s most important to patients. If you have chills and fever and high CRP, is that a flare of an autoimmune disorder? Maybe it is, and maybe it isn’t, but the patient will want to know. And it’s stressful for rheumatologists, they often can’t give the patient a clear answer… and I think when they offer a guess, they’re more likely to be wrong, just the nature of the beast. Mickey was kind of kidding around, but his point was just that all that ambiguity keeps clinicians up at night.

Mickey was the first person who explained the vascular abnormalities that are a part of many rheum disorders. My own rheumatologist actually asked me, “Why did you get a blood clot?” As registeredforthissite mentions, however, the odds of actually getting MRI imaging done are remote in rheumatology as well– until the damage is bad enough to cause symptoms, at that point, the expense would be more easily justified. Is that brain fog just an inflammatory issue, which would be more of a kind of reversible dementia, or some more insidious progressive micro-infarct process? Gets a little murky.

I thinks this speaks to your point about osteoarthritis as well… inflammation is one of many things that can cause osteoarthritis, and rheum disorders are one of many things that can cause inflammation. But it sure would be nice to know the cause of the inflammation, and initiate treatment, BEFORE the damage is done, but in the real world, that’s not gonna happen.

For a patient, all that ambiguity is stressful, too, in a way that has some significant similarities with psychiatry. One could argue that DMARDs are more likely to be effective for rheum patients than psych meds will be for psych patients. But like psych meds, they are really blunt instruments, and there’s a real question about whether the DMARD side effects will kill you faster than the underlying condition.

Report comment

I live in India and my non-contrast brain MRI (which came clean) cost me 60USD here without insurance. That’s right. Without insurance, direct cash payment. Sure, we have to take purchasing power parity into account because our salaries, costs of living etc. are lower, but even after accounting for that, healthcare costs are not even close to being near US levels.

In the US, the MRI I got would run into thousands of dollars. This is part of the problem. People there are told about brain imaging, but when they want those scans, they likely run into the problem of not being able to afford them or not having permission to get them (for whatever reason: doctor won’t allow, insurance won’t pay etc.).

Over a decade ago, when a pompous psychiatrist hell bent on defending his profession told me about MRIs and fMRIs, I had no brain scan to shut him up. I have one now, but I’d like to do more if possible. fMRI, PET, Ultrasound…bring it on.

Report comment

I had drug reactions before I developed akathisia, more typical urticaria etc. plus some of the rarer effects.

I now see this as a red flag for developing a more serious reaction and developed tardive akathisia from an acute reaction to metoclopramide, prescribed for reflux.

I agree with both yourself and Stuart about the fact that mechanisms are poorly understood and struggle with what the difference us between delayed withdrawal and tardive symptoms? also how many different classes of drugs cause akathisia that have little to do with neurotransmission, antibiotics for example.

As stuart said there is no actual causal data. Honestly I think I would choose to use caution around terms like withdrawal, but whatever the explanation hyperbolic tapering works for most people.

My heart breaks for those people who tapered over years battling neurosymptoms only to have tardive akathisia intensify after the last drop when their resilience is totally depleted.

I cut my meds following developing tardive akathisia, three months after my original reaction (a PPI) and my akathisia intensified massively. I think that this was probably the right thing for me as I would not have had the reserves to face the harsh backlash of akathisia after doing a prolonged taper. 6 years later my akathisia stays very low as long as I do not trigger a flare. Lately I note intensification of peripheral neuropathy after a flare, there is evidence of increased nerve impingement in my fingers. I think inflammation of the nervous system is very likely, i’m now a part time wheelchair user.

Report comment

I’m curious, do we know of any studies regarding using psilocybin to help with titration? Seems to be a promising emergence regarding serotonin. Also Lions Mane supplements have been shown to help regenerate nerve endings.

Report comment

3dogMama can you share where you found that Lion’s Mane supplements have been shown to help regenerate nerve endings? I would try them.

Report comment

I used microdosing to get through the withdrawal, but 20 years of SSRIs have done their damage.

Report comment

Another important but likely exasperating subject for further study. Anecdotally, it’s always seemed to me like people who’ve been exposed to LSD or psilocybin are far more likely to react very, very badly to SSRIs. But I couldn’t begin to guess how it would work the other way around.

Report comment

This is incredible and also humbles me because I did the same when looking in hindsight to see how my words could have had adverse affects on others, instead of what my intentions were. Which was only speaking my truths, research and how I trusted my intuition. I didn’t realize at the time that warning people to make them aware and making sure longevity and their quality of life, extended; could have been also people not giving full wrap around knowledge as to the whys and hows of you knowing yourself vs trusting blindly someone who can only go on what your knowledge is. Which is the trap. My body was saving itself due to it being in survival mode. Jargon and language are vital. They don’t call it spelling for no reason.

Report comment

Thank you for writing about this supremely important issue; that there are people who cannot get off these drugs and there is no way to know in advance who they are. I wonder if the taper experts charging a fee to instruct people on how to taper are informing people that there are no guarantees they will avoid protracted withdrawals.

I’m at the very end of my 5-year taper off Cymbalta. I’m holding on the last microbead. Four years ago I got delayed akathisia from going off it in 8 months and was extraordinarily lucky my brain accepted late reinstatement and cured the akathisia. I proceeded to slowly taper off the 30 mgs I had reinstated.

I’ve been feeling completely normal because I respected any withdrawals I felt and held each bead drop after 8 beads for months at a time. But last week something very upsetting happened and it triggered some akathisia symptoms. The symptoms have abated, and then I read your paper. I was feeling pretty confident that I could stop this last bead in another month. Now I’m terrified to ever stop it.

Report comment

I think the author uses too much sciency serotonin lingo in this article. We are finally at a point where researchers, clinicians, and key opinion leaders acknowledge these drugs may not impact serotonin nor its receptors. As such, the mechanism behind withdrawal and withdrawal symptoms may have nothing to do with serotonin or any neurotransmitter or two. Nor BDNF, which was also mentioned. Again: we have no way of measuring any of these chemicals, and they are not our focus. We cannot fall into the same assumption getting off these powerful medications as we did watching tv commercials for them 2 decades ago!

Report comment

As a GP I read your book on informed consent for Antidepressants – and felt that you stressed if people had been on these drugs for more than 5 years and especially if more than 10 years it could be safer to leave them on the drugs as severe withdrawal reactions like akathisia could not be predicted. I wish we could really get the prescribing of these drugs right DOWN as very poor evidence for benefits vs placebo – and the clear message out that if started at least really limit the time frame for which they are used with clear plan to come off them within a couple of years.

Report comment

Stewart,

It is very refreshing to read this piece. Your focused and dedicated attention to the reality of this situation, which is very dire for everyone just trying to survive it while everyone else is trying to look the other way, is really fantastic. It says something very particular about those who are not looking away.

Aka is a central problem because it is really the principle messenger of what is really happening to our physiology when we are injured, the culmination of continued agitation to an injured nervous system in my opinion. I want to tell you about what I have learned in the hopes it may lend you some insight in your endeavors because there, again, are very few making the honest endeavor to quell this predicament.

I admire Healy and your endeavors to understand what AKA is diagnostically, I think those efforts are needed but I am not sure if they are practical. There is no guarantee they will yield anything in a timely manor. I think it can be more helpful to be generalistic until that effort is ready to yield applicable fruits. It reminds me that when it comes to withdrawal and injury the folks that introduced these drugs and treatments had virtually no idea what they were doing when they started treating people with them, so in my mind it seems that if we try and figure out exactly what they have done, we will always be about thirty or more years behind the ball. I know it does seem like we have nothing but time on our hands while we are trying to overcome these issues because it seems impossible but I think the grandeur of the human imagination can often overcome these problems if only we trust our innate abilities rather than our intellectual ones. I digress, but I do think contextually understanding where we are and what is possible is important as it often directs our efforts.

First off I am glad to see Samantha Long has already commented here, I have learned a lot form her and she is worth talking to if you find the desire and time to hear her experiences and knowledge about this topic. She provided me breakthroughs that I would not have found otherwise by her insight and experience.

Next, I find it very interesting AKA is not just from psychiatric drug withdrawal but can come from any head injury. I had my first bout of aka about 4 years after my TMS injury which blew my socks off to say the least for a lot of reasons. I believe it was from the agitation of the TMS injury, from severe neurological stress. What does that mean?

It means that my resulting psychological state from my TMS injury was one of prolonged deterioration because of continued dysregulation of my nervous system (extreme fatigue then panic and stress, and most days both at once – this is called tired and wired in some circles which I will get to) and a lack of joy or rather positive psychological stimuli. In other words my TMS injury, also a repetitive head injury just like meds, caused a downward trend that brought on the aka when that magical neurological threshold was broken. I imagine this happens when we have been locked into fight or flight for so long that the body is truly exhausted at a fundamental level and I would imagine there are biological markers for that somewhere – poor psychology and thinking is responsible for gene expression as well over time.

This was a bit of a revelation when I experienced aka, I then realized many others with TMS injury also had aka, but they just weren’t calling it aka.

After toiling with this for quite awhile(This is very light language) I ran across information on fasting and then prolonged water fasting. I completed a prolonged water fast which put my aka into remission for the last six months(and it still is now), but this is not the most important piece of information I discovered. I discovered that when I expanded my search on neurological harms, there are a lot of other people out there experiencing the exact same neurological symptoms and phenomena that we are(the psychiatric injury community). I spent quite awhile learning from them and closely examining their stories and data. It appears to me that neurological injury resulting in dysregulation inhibits the bodies ability to heal and regulate itself, which seems self evident but it is profound. Since the CNS regulates the rest of the body – once it is agitated or injured it is not very good at both healing itself and regulating itself again. There is not separate self contained healing system or back up for the human body, the CNS is at the very top of the command and control list. Kind of like trying to fix a plane while it is in flight, the level of complication is extremely accelerated.

I had been told several times that I should look at the CFS/ME community when I was also diagnosed with CFS in addition to my other issues. I put this off because i automatically assumed it was much different than what I was dealing with but after having recently expanded my search I started seeing overlap and then I saw that CFS is not even really about fatigue, but rather severe neurological dysregulation. Many of them complain most commonly about being both tired and wired at the same time. I then began examining other things like PEM or Post exertional Malaise and I Realized that i experienced the exact same things. Many of them also have intense pain syndromes and sensations, not unlike myself and others as well as many things I have read about in the Benzo community.

These revelations struck me firmly and I started looking deeper into them, and when I did I realized that many people were publishing information on how they had recovered from CFS/ME and the strategies they used. The strategies that I found mirrored many things I had tried however they seem to have a better grip on exactly what was at the core of their recoveries – neurological rest – this term became essential in understanding the fundamental problem which is how we can get the CNS to regulate itself when it, itself is damaged and harmed, remember fixing the plane already in flight. As I looked at their strategies and what had worked for me, including my prolonged fast, I realized that the CNS can regulate itself if it can get rest. If it can be devoid of all of its other tasks it can put itself back together.

Why is it that meditation works for some and not others? Why is it that intermittent fasting seems to help some people in some ways? Why is it that people who are able to find some happiness to get them through withdrawal seem to fair so much better than others?

From what I have learned these things are all related to neurological rest. Fasting relieves the role of the CNS from digestive processes and load which is a huge task and requires a huge amount of neurological energy. Meditation clears stressful thought patterns and gives rest from environmental stimuli, Good or happy interactions and events clear stress from our thoughts and reinforce pathways of joy and peace.

A big obstacle to these things is repetitive negativity of the human mind, and so if we do not diligently abandon all the negative thinking patterns and trauma of the past both from withdrawal, injury, physical and psychological trauma we can’t really get rest. However, if we do and we consistently apply these and similar methods over time the rest provided to our CNS will yield regulation and that regulation will give way to organically positive sensations and experiences which will get us further and further away from aka and other unpleasantness involved in the injury.

This may be controversial but my findings seem to mirror yours, I am not particularly sure how we taper is indicative of whether or not we will get aka or other unpleasantness. I do know that being erratic with withdrawal without getting the neurological rest from fasting or other techniques will likely yield some really unpleasant results – which i experienced myself in the past, but I do not think this is the core issue. I think the core issue is a myriad of factors based on people personal situation and the availability of the CNS to be able to get what it needs to regulate itself and rectify the abnormal and toxic state brought on by both withdrawal and repetitive and traumatic head injuries which can also be brought on by severe or chronic psychological stress not just chemical, electrical or overt physiological head trauma.

Thank you for your work Stewart, and this piece.

Report comment

I think kinda “pruning” as hypothesis for akathisia might not be that good: Rare folks who start an antidepressant developed sometimes severe akathisia within 4, four, weeks of starting SSRIs.

And the unpredictability in time, individuals, circumstances, etc., of akathisia, makes me dubious it’s an anatomical thingy.

But I have an alternate biased hypothesis that could potentially explain the variability in time, within and between individuals:

THE BRAINSTEM.

First, in disclosure, my bias: I think Havana Syndrome is a tardive effect of exposure to psychotropics, covertly, overtly, unrecognized or unacknowledged. Not the effect of an “ultrasonic” ray gun, nor “mass hysteria”.

Now, how and why the brainstem?: many soft, hard to categorize symptoms AND signs, difficult to put in a “syndrome” in neurology are related to the brainstem. Small anatomical lesions there, like in dead neurons, are difficult to study even at 7 Tesla.

As an example of the useless of MRI dead neurons being absent is that the pathology of the arcuate fascicle in no mental illness as far as I imagine has not been described, and it is thick!. And it probably, most definitively if schizophrenia was a brain disease it would be severely “dysfunctional” in those cases.

That’s my why.

My how is: probably the brainstem works in many different varied contradictory ways in the course of one’s life, in the course of one’s day.

Precisely because the brainstem is involved in so many vegetative and willing functions, like sexual pleasure and orgasm, it’s circuitry probably fires differently whether one’s riding a bike, hanging like batman from the ceiling, watching a movie, riding a train, driving a car, or having intercourse.

Eating, drinking, laughing, gazing, sleeping, running, walking, showering or just standing will look, to my mind like the old batcomputer in the brainstem: a bunch of light bulbs are on in one situation, off in another, and yet another, and so forth. And a tiny variation even in head posture might change it’s dynamic state.

And it’s current state is probable previous state dependent. Like a classical single tape digital computer…

It’s no mere analogy for me, that could give a stocastical flavor to a terrrible bad outcome, described as side effect. And hard to analyze if neuroanatomy and neurophysiology really haven’t progressed much in describing the circuitry of those “vegetative” very small, but very relevant group of neurons, particularly in the reticular formation.

How would that explain the crossing over into tardive akathisia?: CHAOS theory, dynamical systems.

Sometimes systems start functioning on a different configuration, a different set of “behaviours” connecting inputs and outputs.

A different long term state, kinda of a closed tight, restricted loop of now available functional states, in computational terms.

A new way of functioning starting apparently from small perturbations on an already at tipping point system. What most knowledgeable people call a “crisis”, it could go either way.

And that could explain why akathisia might appear to come from nowhere: it could be a vegetative reponse that comes from a vegetative, unconscious, reticular formation.

Now, how my fantasy give anyone experimental hypotheses? Beats me, last time I read about the reticular formation was over 30yrs ago…

But from an armchair neuroanatomy fan with a touch of frustrated mad scientist, it makes sense.

Report comment

Another appalling tale of the harms from psychiatric drugs that virtually no one is warned about when they are first prescribed by a doctor. Do any doctors tell patients about the possible harms, alternative solutions, possible benefits, and what it will look like to withdraw from the drugs? I really can’t think of much that would be worse than suffering from akathisia after taking drugs that are supposed to improve my mood…….Tragic.

Report comment

It took nearly 20 years for any meaningful action to be taken against the lucrative Opioid nightmare that took hundreds of thousands of lives. It probably will take 40 years + for anything to be done regarding the psychothropic storm causing enormous harm in the US. Once there is little profit to be made both the generic and brand drugs then the tide will turn.

Report comment

And even then how much justice was there really for opioid victims?

Report comment