Many years ago, along with several other psychiatric aides, I participated in tackling a youth who hadn’t followed his behavior management “treatment plan,” and forced him into a seclusion room. I was new to the field and did as I was told. But the violence of the act left me upset and perplexed.

The psychiatric hospital where this took place had been founded by Mennonites—a religious order with a strong pacifistic tradition. How was I to square the violent restraint and isolation of a vulnerable patient with the values supposedly espoused by the hospital at its founding?

Naively, I asked the psychiatrist in charge what to make of the situation. The psychiatrist told me a story: One farmer visited another, hoping to buy a mule to do some work around the farm. The seller described a good animal—obedient to commands, strong, and healthy. This sounded good to the buyer, so he paid the farmer and began hitching the animal up to leave. However, the mule wouldn’t obey his commands. The seller walked up and whipped the mule… and it started moving. The seller explained that the animal was obedient—once you got its attention.

To that psychiatrist, the patient who hadn’t followed his “treatment plan” was a disobedient animal, and cruel punishment was simply what was required to get his attention—after which he would presumably follow his treatment plan.

But this left me even more confused. I didn’t believe that this kind of violence was an ethical method of getting a person’s attention, nor that blind obedience was the most important element of psychiatric treatment. How could a Mennonite hospital have ended up with values like this?

To answer that question, a history of the intersection of Mennonite values with the medical model is in order.

The Mennonites originated during a period of unrest and wars in Switzerland and the Netherlands. They were considered part of the “Radical Reformation,” a movement now 500 years old which placed a high value on nonviolence and pacifism. While there were others, a village Catholic priest, Menno Simons, began to articulate an understanding of the Christian faith that love for one’s neighbors and as an expression of that non-violence and pacifism. Some of the early leaders began to question compulsory military service. Another controversial belief was that infants should not be baptized and wait until they were old enough to know what becoming a Christian actually meant. While this may sound innocuous enough to us today, in a wider sense it called into question loyalty to and membership in the state and the church.

These beliefs led to persecution and the martyrdom of thousands of Mennonites. Unable to safely practice their spiritual views, many moved their families to parts of Poland and Germany. In 1787, the Russian emperor, Catherine the Great, promised them freedom of religion. Thus, when they found themselves unwelcome in Poland and Germany, many of them moved to what they called South Russia, now known as Ukraine.

Although it took decades after they had presumably begun to recognize there were people who were considered “mentally disturbed” in their closed Russian villages, in 1910 they started their own psychiatric hospital, Bethania. It was modeled after a Protestant facility established in 1867 in Germany, Bethel-in-Bielefeld, known for its commitment to healing and care and later for its resistance to growing antisemitism in Germany. In this spirit, the Mennonite’s Bethania served more than just their own: By 1925, half of the patients were Russians, Germans, and many from nearby Jewish communities. This facility was taken over by the Russian government in 1925 and closed in 1927 to make way for a power dam.

However, the influence of Bethania’s spirit extended to Canada and the United States when Mennonites continued immigrating there and finally again acknowledged there were individuals who they viewed as “mentally disturbed.” One of these persons was a minister who was facing deportation. A social worker, Henry Wiebe, who had a farm in Vineland, Ontario, agreed to take in the minister and cared for him. It turned out that Wiebe was already familiar with the philosophy of hope and care for people with mental health problems, having worked at Bethania for three years.

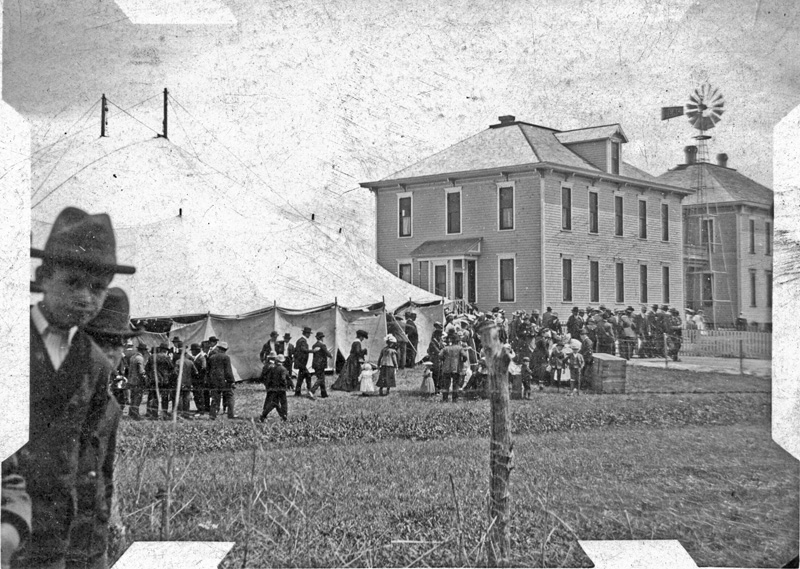

Whether he recognized it or not, this farm had similarities to what the Quakers had created in Philadelphia in 1814—asylums that implemented “moral treatment,” which was a therapeutic approach that called for humane, respectful treatment for all who came in contact with an individual there. An observer noted that “the whole spirit of this hospital is in the tradition of a genuine, warm Christian family in contrast to the harshness of a huge institution of a provincial mental institution. The patients carry on quite a normal life, not living under lock and key, daily working on the farm, eating and worshipping together…It is this type of custom which builds a real sense of security more valuable than [the] most highly developed scientific therapy.” The very first patient recovered, avoided deportation, and returned to his family. Wiebe began taking in more people, naming his farm-turned-hospital “Bethesda” after Bethania.

Mennonites’ next encounters with mental health soon came about during World War II. Hundreds of pacifist Mennonite young men and women, conscientious objectors to war, were assigned to work in understaffed state and provincial hospitals in the US and Canada. Knowing virtually nothing about these “asylums,” they were shocked. They witnessed the monotony of life there. They saw the dehumanization and contempt for the patients. They saw frequent assaults by staff on patients and patients on patients. They saw frequent use of mechanical restraints, segregation, and discrimination. They saw hospitals like Philadelphia State Hospital, with 6,000 patients but only 200 staff. They saw beatings. They saw hospitals where the staff carried blackjacks. They saw children crammed into fire traps a hundred years old. They saw murders.

They provided much of the tragic material in interviews for Albert Maisel’s highly influential Life Magazine article, “Bedlam, 1946, Most US Mental Hospitals are a Shame and Disgrace.” These stories paralleled those in the now better known 1948 classic by Albert Deutsch, The Shame of the States. As with Maisel’s article in Life, Deutsch’s main goal was to bring to the public an understanding that the patients confined in state hospitals who deserved humane and caring lives when they were getting absolutely none.

As the young men and women returned to their home communities, they began to express a desire to do something with their experiences. A group of them entered into discussions with other church leaders to consider a future of caring in contrast to what they had seen in state hospitals. They established psychiatric hospitals in California, Kansas, Indiana, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ontario (Canada), and even in the Chaco of Paraguay. They made common cause with an existing relief organization, Mennonite Central Committee and, I would say fatefully, with mental health professionals.

This was a pivotal moment. What all previous Mennonite efforts had in common was that they were not based on the medical model. Yet, something happened then to conflict with nearly 500 years based on bedrock values of non-violence and humane care. How did the change in models lead to the seclusion and violent restraint illustrated in the story beginning this blog?

It is not really surprising that their psychiatric facilities were hospitals, rather than something more like that of a Quaker moral treatment program. Virtually none of the returning conscientious objectors had ever heard of the Quaker non-medical model of care.

The leaders in establishing the hospitals were almost all laymen. The few psychiatrists were all very much mainline in training and practice. Given the medical model’s credibility and authority to them, there was not an understanding that in important ways it differed radically from traditional Mennonite articles of faith. To those who planned and established the Mennonite psychiatric hospitals, this aspect of the likely use of force likely didn’t occur to them. To the degree that some anticipated a psychiatric hospital would make use of coercion, the violence of seclusion and restraint would be justified as therapeutic.

The medical model at that time used damaging “treatments” which included electroshock, insulin shock, hydrotherapy, and “security rooms.” But the prevailing notion was that these treatments were more humane, more appropriate, more sophisticated than what had come before—that these treatments would ease suffering, even if by inflicting it temporarily. In the same way, when psychiatric medications were introduced in the 1950s, the assumption was that they held great promise and were then used in such a way that some of the previous treatments (insulin shock therapy, for instance), were eliminated. Yet the use of physical violence continues, electroshock continues, drugs with powerful harms continue, and all while rates of “mental illness” continue to skyrocket.

What to take from this:

The medical model is powerful. Mennonite efforts began operating from a non-medical paradigm in Ukraine and Canada. They found ways to care compassionately. In World War II, their moral convictions led over a thousand Mennonite to speak out and challenge the evils in state hospitals.

Following those experiences, though, they brought the ideas of psychiatry back to their home communities. They provided church leaders with information that led to the establishment of seven psychiatric hospitals, which then led to adopting the medical model, as was the convention after World War II. That marked the beginning of a transition to that model.

The transition included the adoption of a range of services: drugs, shock treatment, and behavior management for adolescents. From there it was a natural acceptance of consequences like seclusion and restraint. It contradicted 500 years of the Mennonite tradition of non-violence and humane concerns, but when questioned about why the use of violence and force was acceptable, there was a ready answer, consistent with the medical model rather than a kind of moral therapy they had used.

Despite being established by Mennonites, for whom nonviolence was central to their creed for hundreds of years, the medical model made violence acceptable, even considered to be appropriate “treatment.”

A hospital by definition is based on the medical model. Given their susceptibility to ignoring humane concerns and allowing violent practice as the “standard of care,” they must be monitored constantly to ensure the safety of residents. I would adapt the words of John Philpot Curran to say that the price of freedom from violence in the medical model is eternal vigilance. Maybe it would be better to abandon the medical model and move on to a paradigm of humane care.

Bob, your history of the Mennonite Care Communities fulfills my long felt “need to know”. I don’t think I could have found a better resource than this to share with others.

Report comment

Thank you, Carol. I’m really glad you found my blog useful. One of the main sources for my piece is the book. If We Can Love: The Mennonite Mental Health Story, edited by Vernon H. Neufeld. I kind of doubt it’s still in print but the publisher is Faith and Life and Life Press in Newton, Kansas

Report comment

Thank you, Bob. So kind of you!

Report comment

Hi, Bob! I just placed an order for “If We Can Love: The Mennonite Mental Health Story” through thriftbooks for $8.99 plus shipping and tax. Paperback in Acceptable Condition. My preference rather than going with Amazon for $48.70 new.

Report comment

“Maybe it would be better to abandon the medical model and move on to a paradigm of humane care.”

I agree wholeheartedly. “That’s me in the spotlight losing my religion,” twice. My childhood religion also “partnered” with the “invalid” and violent “medical model,” so my family had to leave that religion. But both me and my mom still miss our former friends.

It’s very sad when the mainstream religions “partner” with the “medical model” … due to greed. And an ELCA pediatrician did literally confess to me – after I medically pointed out the iatrogenic etiology of all the “serious” DSM “disorders” to her – that she couldn’t stop drugging the children, “because it is too profitable.”

https://www.amazon.com/Anatomy-Epidemic-Bullets-Psychiatric-Astonishing-ebook/dp/B0036S4EGE

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

The greed of the scientifically “invalid” psychiatric and psychological DSM based “medical model” destroys lives, families, and friendships. But as the real Bible states, “the love of money is the root of all evil.”

It’s a shame too many mainstream religions have “partnered” with the “bullshit” of the “medical model.” The religions should be fighting for “humane care” of all, rather than the mass drugging of children, for profit.

But since the religions own many of the hospitals, we are dealing with corporate greed, and religions who care more about profits, than ethics and common decency.

Report comment

Behind the medical model is the ancient practice of AUTHORITY of Truth with Social Power. The medical model has replaced the older authority of truth and power. That is, the church leaders tied with kings of wealth. This time medical as truth tied with wealthy business owners.

And dont overlook how the educational institutions pave the way that place value on information as hierarchal such as math and science, especially biology and chemistry, that dehumanizes and dislodges humans and their environments while looking through lenses of tiny particles not seen by the naked eye. It directs where one should look and how to think. It blinds and obliterates the ability to see what is right straight in normal eyesight. Living th through Technology destroying life.

Report comment

Thanks, Bob, for a very thorough examination of the mental health thread in the Mennonite history over five centuries. Good intentions and spiritual values eventually end up face-to-face with the realities of orthodox psychiatry and funding needs. I had the privilege of working in outpatient settings in a Mennonite mental health program for twenty-six years in the San Joaquin Valley of California. We were fortunate to attract and keep staff who valued the Mennonite mission statement (“To provide community mental health and social services to those with limited resources, and to do so in the spirit of Christ’s example of love, compassion and respect for all persons.”) even during times of financial challenges. Your research here also keeps that mission statement alive.

Report comment

Fascinating! I am an autistic Christian and have found great solace in churches with Neurodivergent pastors. Jesus welcomes everyone, and I think the problems associated with the facility here is that the government took it over and secularized it. They need to get Neurodivergent Christians to redesign it to be an open ministry.

Report comment

Absolutely awesome article, thank you!

A clear understanding of our past makes possible a joyful present and future.

“You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free,” and to “emulate” means to equal OR exceed…

Heartfelt thanks.

Tom.

Report comment

Electro shock therapy is kind and gentle these days. I had it and returned to a very successful technical career. Sometimes it is the best choice. Do not make up your mind based on movies or fictional accounts.

Report comment

Most of these people have HAD ECT themselves or know someone who does. Many also know the ECT research literature better than the average clinician.

It’s insulting to suggest that anyone here is making up their minds on fictional accounts. I’m glad you had a positive experience to report, but don’t assume others experienced the same or similar things!

Report comment

Why silence people who had horrific experiences with ECT? I did. Do I not matter?

Report comment

Each time I re-view, listen to or read this TED talk, I become more convinced that the electricity itself had nothing to do with Sherwin’s recovery. But then, that is what I want to think, too.

Each time, I discern more clues that the man totally misunderstood what had happened to him.

It seems a particularly academic trait, possibly as our cerebral neurons ossify, that as we age, we increasingly effortlessly transform our prejudices into cast-iron theories of mind, much as Oliver Sacks seemed to me to do, too, in his talk in which he assumes brains conjure random visual images out of nowhere, forgetting that there is and can be neither true randomness, Oliver, nor coincidences, Sherwin, but only worlds unfolding as they should and must?

https://www.ted.com/talks/sherwin_nuland_how_electroshock_therapy_changed_me?language=en

https://www.ted.com/talks/oliver_sacks_what_hallucination_reveals_about_our_minds/transcript

My other prejudice is that we can all get over our conditioning and brainwashing and our tendencies to be misled by the prejudices, proclamations and assumptions of trusted authority figures, academic, clerical or otherwise, and think and be for ourselves.

According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Council_of_Nicaea , some few hundred of the 1,800 invited bishops attended the First Council of Nicaea, along with followers.

Did the good guys stay at home, refusing the offer of help, hospitality and whatever else from a Roman emperor not known to be a practicing Christian?

Who knows.

Did Jesus, the man and healer, burn himself out? Who knows.

If I said,

“Hey, man, go pinch an ass for me, willya?”

And one of my acolytes (you know, one of the guys who laughed at me when I asked who in the crowd had touched my cloak, one of those guys who told me to send the Canaanite Woman away) replied,

“I beg your pardon, Lord?”

And I replied, “I don’t care – an ass, a colt, a mountain bike, anything: my feet are killing me.”

And he replied,

“Oh! And, and what if the owner confronts me, Lord?”

And I replied,

“Tell him I have – tell him your master, or teacher, has need of it!”

And he replied, “Oh, right.”

And then if I beheld a fig tree up ahead and asked if it bore fruit, though this was not something fig trees did this time of year, and was told No, and cursed it roundly,” would you think folks might think I was fully human and therefore fully divine, just like everything else in all Creation, or, instead, some kind of nonhuman alien in human disguise?

And yet the Council of Nicaea, which came up with our Nicaean Creed, would have us all believe that the same guy who, according to John (of ALL the Evangelists), said, to mere mortal men, something like,

“Such things you will do, AND greater, too…”

was not begging us, being made of the same stuff as he was, to emulate him – to equal ANd exceed his works, not because we are less or more than Jesus (the man) was, or than Christ (the divine) is, but because we are all equal?

When is a circle equal to a square? When it is infinite, I guess?

Thank you, Bob. And Sherwin. And Oliver. And Jesus. And MIA.

Tom.

“Yes I know that love is like ghosts.” – “Love Like Ghosts,” by Lord Huron.

“Via veritatis, via caritatis!” – Angelo, Giuseppe Roncalli, the Good Pope”(!), John XXIII – THAT angel.

Report comment

I would like to know the range of demographics of the residents-in-need who lived in community in these farms. Were men and women equally represented? Whom was accepted and whom was rejected?

A local doctor said that before the age of antibiotics half of the hospital beds were for people with mental illness caused by venereal disease. Was that linked more to urban demographics or rural or both?

Additionally, one could suspect the neuronal injuries from scarlet fever (strep), parasites, or vitamin deficiencies to cause mental challenges. Dr. Robert Lustig of Metabolical wrote that before the industrial revolution disease was usually caused by nutritional deficiencies , but now today we suffer from metabolic illnesses caused by what and how we eat, not to mention the psych meds that cause metabolic problems.

Those in recent years who have tried farm-communes have reported how difficult it is to keep these arrangements going and productive enough to support everyone. To reproduce a Mennonite-style community would require a generous benefactor and sophisticated conversion of a campus with grounds and some blend of mechanization and manual labor so that humans can metabolically function the way natural selection adapted them to the biosphere. The AI take-over, how will that impact prospects for caring communities.?

Report comment

Thankyou for such a gentle, though-provoking article. I wish to goodness, we could turn the clock back and do as you suggest – abandon the medical model and move on to a paradigm of humane care.

Report comment

Carol, very interesting observations.

We tend to assume that we humans have long ago outstripped Natural Selection, Evolution, Nature.

On what do we base this assumption, though?!

And is it valid?

If not, then…

Our modern Western diets MAY be typically deficient in Mg. If so, this may explain some perceived benefits of lithium prescriptions.

Thank you.

Tom.

Report comment

Way I see it, the old bibles taught that human beings, by their nature, are not natural, but are flawed creatures, miscreants, you might say.

If their creator were capable of anger and other negative emotions, as those old books taught, then this may indeed have made some sense.

The exquisite harmony of this cosmos, to the extent that I have been able to glimpse such harmony, suggests to me that the Intelligence responsible for it, and that responds to it, is at least infinitely more mature than to fall prey to stupid human emotions.

Following this line of reasoning and speculation, I deduce that the increasing angst which appears to have been agitating Western societies, at least, must every last but if it be an essential part of our evolution towards more wise and loving and mature creatures

If it takes atrocities and atrocious wars and diets and DSM’s to get us all there, then I pray we may be like those early Mennonites who were sufficiently graced to somehow see through the madness of war and anger and grudge and bitterness and conflict.

I see this as being an extremely useful essay in highlighting our collective and individual human capacity to ask for and receive courage, grace and insight…and even to see that the moment we have found the courage, grace and insight to pray for, wish for, ask for it demand more of the same….we have already been graced with it.

Some have called Eckhart Tolle’s “The Power of Now” a “bible du jour.”

I expect we may look back on it and on his other books as being more than infinitely more than that, and more like the ultimate hitchhiker’s guide to the planet, the galaxy and this cosmos.

I could be completely misguided, of course.

So could those Mennonites have been. It can be hard to stay in track, and to see when the blind are leading the blind, and where to.

But when we read an essay like Bob’s, above, or words like Bob Whitaker’s, I reckon Truth resonates in all of us, and we can see our true path forward once again.

Thank you.

Tom.

Tom.

Report comment

Tom, I had time, while my wife is in Washington DC and I’m missing her, to re-read your comments and want to thank you for your very kind comments about Bob Whitaker and me. My Mennonite modesty, which I don’t always keep in enough check, admits to being challenged by your remark. I do hope some Truth does resonate but I appreciate your perspective very much and just wanted to tell you. Bob

Report comment